By Emily Browder

Edited by Jisoo Choi '22, Jack Antholis '24, and Esther Reichek '23

At the turn of the twentieth century, the city of Chicago faced an acceleration in Progressive social reform in the face of social and political unrest. An influx of foreign immigrants combined with the rise in southern African Americans fleeing north for economic opportunity led to heightened racial tensions and economic competition. The intersection of Progressive Era social reform and the racial tensions spurred by the Great Migration heavily influenced the juvenile justice system in its origins, development, and legacy as a flawed institution. What began as an attempt to save the city from its social ills, such as poverty, disease, and immoral behavior, eventually became a mechanism that criminalized Black youth, boys and girls alike.

Since its inception in 1899, the effectiveness of the Cook County Juvenile Court in implementing rehabilitating justice for youths has been questioned, particularly in the case of those from marginalized groups. Until the 1950s, historians viewed the juvenile court system in general as a reflection of Progressive Era reformers’ humanitarian efforts at the beginning of the twentieth century: as a reformative institution designed to save youth from the social ills of urbanization.1 In the 1960s and 70s, however, historians began to demonstrate the detrimental effects of juvenile justice courts upon the social makeup of American society and marginalized individuals. Historians such as Tera Eva Agyepong and Mara L. Dodge argue that the courts’ “primary mission was to extend state control over families and children who resisted middle-class notions of proper behavior, sexuality, and family life,” specifically the poor and racially marginalized.2 In this essay, I will argue that the juvenile justice system criminalized African American boys and girls induced by Great Migration racial tensions and Progressive reformists’ varying definitions of criminality. These influenced the juvenile courts’ evolution towards a punitive approach.

Progressive Era Social Reform

Chicago served as the core of the Progressive “child-saving” movement, and was the home of America’s first juvenile court.3 The establishment of the Cook County Juvenile Court in 1899, made possible by The Juvenile Court Act, testified to the widespread concern for children vulnerable to criminal activity. In the process of identifying “at-risk” youth, however, race was a dominating factor. The early twentieth century “marked a time when the city found itself reconfiguring and rearticulating notions of ‘whiteness’ and ‘blackness’ as immigrants from southern and eastern Europe as well as southern Black migrants entered the city.”4

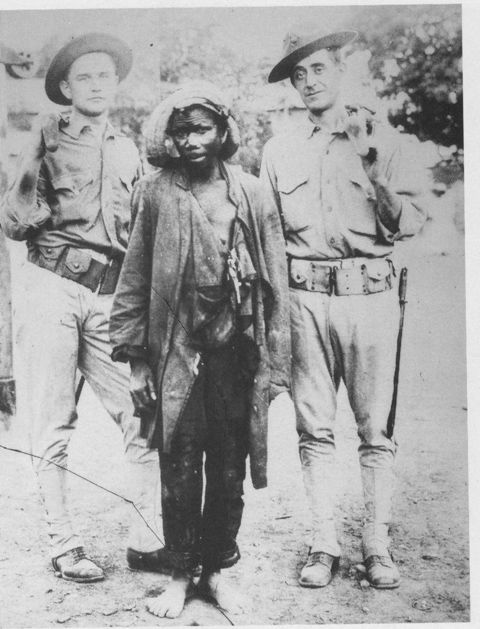

Progressive reformers’ commitment to the rehabilitative ideal led to the emergence of juvenile justice systems on county and state levels across the country, along with discussion focused on defining “delinquency.” The idea that children were the embodiment of innocence and required protection was the ideological foundation that launched Progressive efforts towards “child-saving.”5 Whiteness, however, was a “key component of access to the rehabilitative idea” as “social programs for abandoned children were segregated [and] didn't allow Black children.”6 Those who formed the juvenile justice system intending to protect at-risk children and reform “delinquents” created a system that “articulated racialized notions of childhood innocence and delinquency.”7 African American children, in Chicago and nationwide, were consistently portrayed as “comical, insensate, inferior nonpersons in popular culture.” These social notions manifested themselves in newspaper articles, judicial opinions, and eventual state laws: civic platforms disproportionately associated Black youth with the definition of delinquency.8

When the first juvenile court was established, eighteen was the age at which an individual passed from the juvenile into the adult criminal justice system. Despite this, the court’s first judge, Richard S. Tuthill, transferred ten to twelve individuals under eighteen to adult criminal courts on average every year.9 In 1907, an amendment to the Juvenile Court Act was enacted that “gave the juvenile court judge explicit authority to transfer juveniles to adult court if he so chose.”10 Advocates against this cross-contamination of courts complained that the “gentleman's agreement . . . has broken down. Many dozens of boys have been piled into jails, sent through the adult courts under the criminal law, and imprisoned.”11

Lack of funding was an additional setback for the implementation of rehabilitative justice for youth in Chicago through juvenile courts. Budgetary cutbacks led to “massive firing of social workers and probation officers, even as more and more children came before the court.”12 In 1939, a newly established Citizens Committee on the Juvenile Court attempted to address the deterioration of the juvenile system and to “return to criminal procedure in the affairs of children.”13 These efforts failed. Instead of reviving the original ideals of juvenile justice to focus solely on the prevention of young criminals and rehabilitation, that same year the state “authorized a new maximum-security youth prison, epitomizing the country's increasingly punitive approach toward juvenile lawbreakers.”14

Though the efforts for establishing a juvenile justice system were rooted in the uplifting of at-risk youth, the court deteriorated away from its rehabilitative intentions into punitive incarceration. The court, by failing to recognize how race played a role in defining “delinquency,” became a “bureaucratic machinery replete with scientific and legal classifications, categories, case studies, surveys, and dispositions” that marginalized Black children in Chicago.15 The differential treatment of African American youth proves the failure of these courts to recognize the racism embedded in their development of punitive frameworks, “classifications, court deliberations and dispositions, and facilities.”16 Even the facilities that were available to “save” Black youth, such as The Amanda Smith Home for Colored and Dependent Children, lacked necessary funding that they were deemed “inadequate according to state standards” but “as it was deemed the only substantial facility for African-American children in the state, it was not closed.”17 The establishment of the first juvenile justice system at the beginning of the twentieth century set the stage for discussions on juvenile status, the role of race in Chicago’s social makeup, and the attempts by Progressive reformers to maintain moral rectitude in the midst of rapid urbanization.

The Great Migration and Escalated Racial Tensions

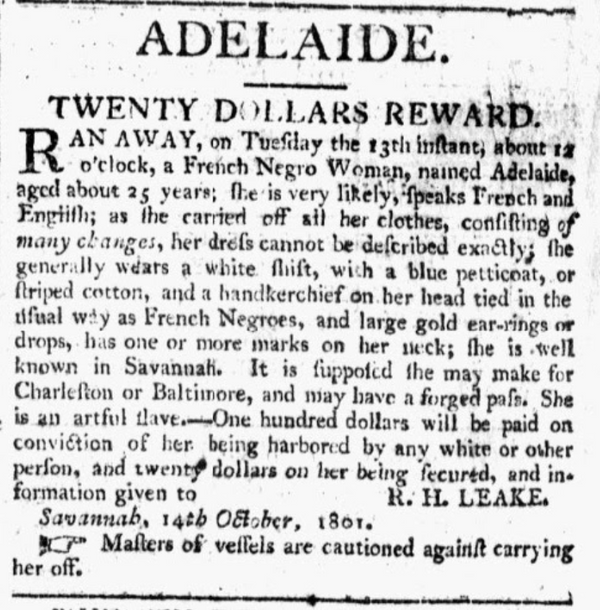

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the twentieth century, a phenomenon called “Northern fever” emerged among Black communities in the South. Letters, rumors, gossip, and newspapers spread promises of higher wages and better treatment in Northern territories. Before 1910, 90 percent of America’s Black population resided in the South, but after the broken promises of Reconstruction, the search for better wages and better lives began to look to the North. Black newspapers in the Post-Reconstruction Era were essential means of communication within the African American community because job opportunities were scarce. The Chicago Defender was founded to share information regarding migrant opportunities, and released a headline in 1917, “Millions to Leave the South. Northern Invasion will Start in Spring - Bound for the Promised Land”: the article promised reduced train fares and special accommodation starting on May 15, 1917.18

This headline, along with the promises of social mobility and opportunity that had been permeating Black southern communities, was extremely detached from the reality of urban Chicago at the turn of the century. The Chicago Defender declared that "there were no special trains scheduled to leave southern stations on May 15th,” but the article itself had already triggered thousands to pay full fare and continue their plan to pursue a better life up North.19 Despite the North’s promise of opportunity, racism and segregation were not limited to the Jim Crow South. A report published in 1913 entitled “The Colored People of Chicago: An Investigation Made for the Juvenile Protective Association” provides an in-depth analysis of the day to day political, social, and economic discrimination Black Americans faced in Chicago. The investigation addressed that:

young people in immigrant families who have passed through the public schools and are earning good wages, continually succeed in moving their entire households into more prosperous neighborhoods where they gradually lose all trace of their tenement-house experiences [...] the colored young people, however ambitious, find it extremely difficult to move their families or even themselves into desirable parts of the city and to make friends in these surroundings.20

The lack of economic mobility that the influx of Black southerners faced played a significant role in the likelihood of criminal activity and subsequent interaction with the established punitive justice system. In a 1917 letter from Jackson, Florida, a man describes “we are [suffering] hear all the work is giveing to poor white peples and we can not get anything to doe at all. I will go to pennsylvania or NY state or NJ or ILL or any wheare that I can [support] my wife” [sic].21 Black fathers who had left the South because they could not find work moved to the North only to be faced with the same employment restrictions and incredibly low wages. The lack of employment opportunities consequently forced the women of the household to seek employment in order to support their families with additional income. Familial financial troubles led to educational problems: “colored children [were] underfed, irregular in school attendance, [made] slow progress in their studies and [dropped] out of school at the earliest possible moment.”22 The intersection of racial discrimination and urban poverty caused Black Chicago youth to be increasingly vulnerable to turn to criminal activity.

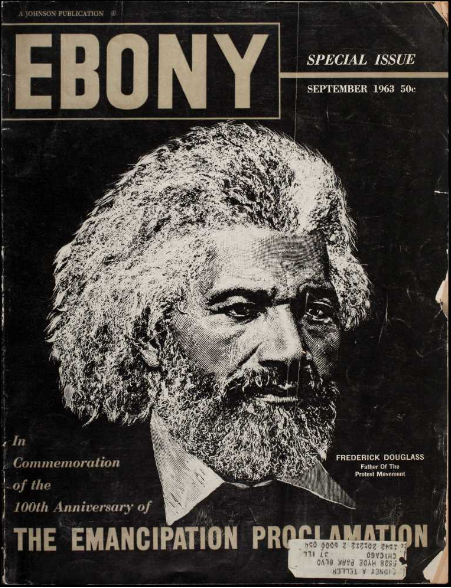

In the early 1900s, the political and social atmosphere in Chicago experienced heightened tension caused by the rapid growth of the Black community. Within ten years, Chicago’s Black population “rose by 148 percent (from 44,103 to 109,458).”23 While the Great Migration was the result of southern racial politics, its effects resonated in the north: the impact of the mass northward movement of southern Black families had a long-lasting impact on Chicago’s social composition and racial ideology. Despite evident racial tensions—shown specifically in the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 in which 38 people died and over 500 people were injured—Black migrants “retained their faith in the promise of the northern city” and “few returned South, except for the occasional visit.”24

Between 1870 and 1900, the total population of Chicago quintupled, and by 1920 its population grew to 2,701,705, more than “nine times what it had been only fifty years before.”25 This rapid population growth led to extreme crowding in poor areas, where in some cases a small frame house would be forced to accommodate three families. In 1902, Chicago was widely known to be the “first in violence, deepest in dirt; loud, lawless, unlovely, ill-smelling” caused by overcrowding.26 Urban density was becoming an increasingly prominent issue; in 1901 it was estimated that 45,643 Chicago residents lived in less than one-third of a square mile. Along with this exponential growth came incessant competition for economic resources that triggered racial animosity between white Chicagoans, European immigrants, and the Black community.

The racial tensions caused by the substantial population growth of the early twentieth century led the juvenile court system, in the face of an influx of poverty and criminal activity, to become more punitive. The juvenile court “became an institution that mediated the tensions [caused by] Black migration” and white hostility.27 Although the public school system had been legally integrated since 1874, “changes in school boundary lines or pupil transfers, resulting in newly integrated schools, often led to white protests.”28 The presence of Black individuals in the North shaped the racial dynamics of Chicago, and the newly established juvenile justice system was not immune to social turbulence. The effect of the Great Migration on the social makeup of Chicago and the evolution of the juvenile justice system “reveals that the criminalization of Black bodies was not geographically limited to the Jim Crow South.”29

Racialized Diction: “Delinquent vs Dependent”

Race heavily influenced the process by which the juvenile justice court of Chicago determined the difference between a “delinquent” child and a “dependent” child. Under the 1899 Juvenile Court Act, a child was deemed a “dependent” if “he or she were orphaned or did not have safe or appropriate parental care due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or extreme poverty,” or generally did not have “proper parental care or guardianship.”30 Comparatively, a child was legally labeled as a “delinquent” if he or she had committed a crime.

For the poor and Black urban youth of Chicago, however, this legal line became increasingly blurry as cases were brought in. This was evident in the case of Mary Tripplet, an eleven year old who was orphaned and thus a dependent child, yet was filed under a “Delinquent Girl Petition” in 1899.31 Similarly, in 1922, the case of Ronald Bird, a thirteen year old from Kentucky, was also filed under “delinquent” even before he entered the juvenile court. In the juvenile justice system, from its origins well into the twentieth century, “poor became synonymous with delinquent, as poor and neglected children often turned to criminal activity as a means of dealing with familial neglect and abandonment.”32 The justification for the undue criminalization of Black youth was that many reformers “pointed to the links between dependency and delinquency: children raised in poverty were often at risk of becoming criminals.”33In the case of Ronald Bird and Mary Tripplet, the combination of their “blackness, extreme poverty, lack of adequate parental care, and youth” set them up to be seen as inherently flawed citizens of society and pushed into the criminal sector before they even had the chance to prove otherwise.34

The racialized process for defining crime in the juvenile justice system was fueled by racial dynamics and economic competition that dominated the social and political spheres of Chicago. Many Progressive reformers began to view the overcrowding and blatant signs of poverty and depression with increasing alarm at the turn of the century.35 When it came to abandoned Black youth, many institutions for dependent children were racially segregated and did not admit African American children. Charlotte Crawley in her 1927 master’s thesis “Dependent Negro Children in Chicago in 1926” noted that there were only “three African-American facilities which accepted dependent children; as such, African-American delinquent children were sent to state institutions.”36 Thus the definition of Black “dependent” children was dictated by the amount of resources allotted to juvenile facilities that could care for them. From rehabilitative intentions, to preventative, to punitive, the institution of juvenile justice categorized dependent Black children as criminals or noncriminals based on resources available to them, not based on a just cause.

The erasure of dependency as a consideration for Black youth in the juvenile courts was implemented by the very bill that instituted the juvenile justice system in the first place. The Juvenile Court Act of 1899, though it succeeded in separating children from adult criminals, did not “separate dependent and neglected children from delinquent children,” stating that “the juvenile court was a hybrid institution.”37 Juvenile court judges, by law, “could commit children who were found dependent or neglected—though not guilty of any criminal act—to an institution.” Within the first decade, judges of juvenile courts committed “41 percent of delinquent boys and 43 percent of such girls to an institution.”38 These high rates of incarceration would remain constant from its establishment through to the 1960s. Despite the Black community of Chicago making up only one-fortieth of the entire population, one-eighth of incarcerated boys and almost one-third of incarcerated girls were Black.39 Well into the twentieth century, Black Chicago youth continued to be “delinquenced” by their association with poverty caused by segregated facilities and lack of promised economic opportunity.40

Gender in the Juvenile Courts

The juvenile courts and their treatment of marginalized youth was a product of intersecting concepts of race, gender-based reform, and the goals of moral rehabilitation. Race, gender, and sexuality all played a role in their treatment and subsequent verdict of young girls who interacted with the juvenile courts. Female Black youth were often viewed as “inherently deviant, unfixable, and dangerous delinquents whose negative influences could contaminate other children in the institution.”41 The racialized ideas of inherent inferiority that pervaded racial ideologies of the South still influenced the institutions of the North.

Black girls were labeled as “sex delinquents,” no matter whether they had participated in a consensual sexual encounter or had been assaulted and, as in the case of Mary Tripplet, were often sent to The Illinois Training School for Girls at Geneva, over 60 miles outside urban Chicago. The Geneva Training School was opened in 1893 with the purpose of protecting “young girls from the perils of city life, as well as from their own sexuality.”42 It was also one of the few institutions to accept African Americans. The majority of girls at the Geneva Training School were committed for “sex delinquency,” but the definitions of sexual delinquency that the courts abided by were broadly interpreted, therefore they encompassed a wide range of behaviors that criminalized young women. Young Black girls were brought before the criminal court with justifications ranging from “accepting a ride from a male stranger, flirting, standing on a street corner, or having sex.”43

The concern for sexual purity stemmed from the ideological engineers behind the Progressive reform movement: mothers. “Protective maternalism,” the brainchild of white reformist women at the beginning of the twentieth century, rose to prominence and had heavy influence over the establishment and subsequent treatment of Black girls in juvenile courts and facilities. The very idea for juvenile facilities was a subsection of the overarching Progressive ideal of ardently fighting against “social and moral evils, such as promiscuity and prostitution” through social reform.44 In the same way that the courts worked to keep young boys on the morally correct path and away from criminal activity, the courts revolved around monitoring the behavior of Black girls as well as young female immigrants of other races to prevent contamination of their sexual purity. The Chicago Woman’s Club, an organization of white female Progressives, was guided by ideas “in their activism [...] which concurrently promulgated women's subordinate economic and social positions.”45 The traditional concepts of sexual purity and motherhood that informed white middle-class female advocacy groups’ platforms simply reinforced the subordinate social and economic status of women, and subsequently caused more young girls to be institutionalized for non-criminal sexual behavior.

The influence of Progressive maternalism at the beginning of the twentieth century was not limited to the city of Chicago but was rather widespread across the country. Mary Odem, in her 1995 study regarding juvenile justice in California, saw parallels between large cities that implemented Progressive reform based on traditional values of womanhood. Odem found that “working-class young women who sought opportunities for social and sexual independence ended up in police holding cells, juvenile courts, and training schools for their morally offensive behaviors” and that “reform efforts led by morally concerned, conservative women to protect girls from marauding men were ineffectual.”46

This concern with sexual morality failed due to its inability to view “deviant” behaviors as a product of their social environment, opting rather for justification based on inherent inferiority. When young female offenders were brought to the court, their “deviant” behaviors were interpreted as “unmitigated psychiatric problems”; meanwhile the social and economic situations surrounding their actions labeled as deviant by the court remained documented but largely ignored. An example of deviancy stemming from an institutional ill was reported in The Colored People of Chicago: An Investigation Made for the Juvenile Protective Association. Here, Louise de Koven Bowen wrote, “colored people of Chicago are obliged to pay such a high rental that a large number of families are forced to take in lodgers, which results in much immorality and indecency among colored people who would otherwise remain respectable.”47 In the context of rapid urban population growth, both overall and within the Black community specifically, the crowding of poor neighborhoods resulted in too many people residing in one home, thus making these widespread and broadly interpreted cases of sexual “deviancy” more likely to occur in impoverished and marginalized communities.

While young women, Black and poor alike, were criminalized for consensual and nonconsensual sexual encounters, the male partners in these cases received little to no legal or social repercussions. Justice professionals, as well as familial accounts, “openly questioned whether girls’ victimization resulted from fervent promiscuity or personal feeble-mindedness,” refusing to see them as victims. Between 1904 and 1927, 60 to 70 percent of all labeled delinquent girls were criminalized on the charge of “incorrigibility.”48 This legal definition could be charged on any girl who “associated with immoral persons, vagrancy, frequent attendance at pool halls or saloons, other debauched conduct, and use of profane language.”49 This broadly interpreted legal definition was liberally applied to young girls brought before the court and led to the over-institutionalizing and criminalizing of female youth in Chicago.

Girls who were associated with sexual activity, whether consensual or not, were institutionalized at incredibly higher rates than their male counterparts. Though girls were in many cases victims, judges institutionalized them for sexual delinquency or immortality more frequently than boys. This was due to the belief that the risk of allowing a “sexualized demon” back into the city served to be “a danger not just to herself but to the larger society.”50 Professionals in the early 1920s such as psychiatrist William Thomas reinforced the idea that “sexual assault [...] as a form of sexual delinquency and a result of girls’ bad choices.”51 He further stated that girls’ sexual “tendency to demoralization” was the result of immigrant, poor, and “disordered” families that needed institutional help to aid their state of living.52

In a similar way, Katharine Davis, a Progressive era social reformer and the superintendent of the New York girls' reformatory, wrote about girls’ prostitution as the frequent outcome of the girls’ being “convinced to engage in relations” and “to become sexual servants” due to weak minds and weak controls at home.53 Despite glaring statistics—70 percent of all institutionalized girls were reported victims of incest between 1904 and 1927—girls were responsible for their own sexual delinquency, regardless of the means by which their first sexual encounters came about. Most institutionalized girls had been sexually assaulted, yet were confined on the basis of their perceived sexual deviancy.54 In 1910, Jane Addams told professional colleagues that almost ten percent of the girls committed to an Illinois industrial school for sexual immorality had “become involved with members of their own families.”55 In 1920, among delinquent girls treated by therapists at the Judge Baker Clinic, almost half reported incestuous sexual relations, and one in five reported nonincestuous rape. In 1930, a study of girls on city streets found that “20 percent had been raped within their families.”56 Despite the abundance of evidence that the girls were victims, these reports continued to link “sexual assault with some form of juvenile delinquency, a formulation that in turn influenced the definition of rape in the early twentieth century.”

Young African American boys received their own form of differential treatment by the juvenile court system on the basis of inherently being associated with criminal activity because of their race. In Jane Addams’ The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, she wrote that cities were “irresponsible and perilous” and that “for boys, delinquency was often a natural outcome of youthful high spirits.”57 Urban schools or jobs, according to Addams, were often “too confining for young men, and it was easy to understand why a boy might quit school or work to join friends in pursuit of adventures that were suppressed by the police.”58 While white criminality was seen as a product of social ills, the responsibility for Black criminality and delinquency fell upon heredity reasoning, parental guidance, or the individual who committed the crime.

Addams is known for establishing the infamous Hull House, a settlement house intended to aid newly arrived European immigrants. The word “segregated” is not often associated with this achievement of Progressive efforts; however, the establishment is an embodiment of the exclusion that Black youth faced despite Progressive reformers’ intention to “save” urban youth in general. The Colored People of Chicago further addressed this discrepancy: “there are not enough places in Chicago where negro children may find wholesome amusement. Idle and discouraged, his neighborhood environment vicious, a boy quickly shows the first symptoms of delinquency, and the remedial agencies which should be prompt in his case are the very weakest at this point.”59 Young Black men were not included in the group that Progressive reformers claimed needed “saving,” and the ways in which White and Black criminality were differentiated became evident in the eventual progression of the juvenile justice system towards a more punitive approach for Black male youth.

What began as a reformatory effort to save impoverished youth quickly deteriorated into a punitive justice system that perpetuated Black criminality. In 1903, the court’s fourth annual report contained statistics on boys who had been called to court in previous years. A significant portion of the boys who had been brought before the court initially had been brought back over eight times within a four year period. By 1916, nearly “one-half of delinquent boys and one-third of girls were repeat offenders.”60 By the 1920s, the idea of the juvenile justice system as a praise-worthy effort had evaporated from the opinion of those who had been essential in its creation. The courts, in their annual reports, did not even continue the process of assessing how many youths had been reformed through court intervention. The public and institution alike had given up on the court as a rehabilitative force. On the 25th anniversary of the juvenile courts’ establishment, past supporters claimed that “the court had become bureaucratic, unresponsive, and overburdened, while patronage political appointments predominated.”61 The Cook County Juvenile Detention Home, which had been specifically monitored by the Chicago Women’s Club during the first decade, was now described as taking on “every appearance of being a jail.” Jessie Binford, an associate of Jane Addams and a Progressive reform advocate, expressed that by the 1930s, the “approach and procedure in our Juvenile Court has become more like a Criminal than a Parental Court.”

The juvenile court system developed into an institution that perpetuated a life-long association with criminal activity and repeat offenses for those who were subject to its influence. The St. Charles Training School for Boys reported that “62 percent of the former inmates had been convicted of new felonies, and of these one-third received prison sentences.”62 In the 1940s, the Central Howard Association, a prison reform organization, attempted to bring the system back to its original intention of differentiating juvenile and adult criminality by advocating for a bill that would raise the “age of criminal responsibility from ten to eighteen years”: the bill was unsuccessful. The Colored People of Chicago’s report sheds further light on the disproportionate extent to which the juvenile courts affected Black youth. The Association reported that they were “startled by the disproportionate number of colored boys and young men [in the County Jail].”63 They also addressed the reason behind this disproportionality, addressing faults within the court system as well as the social association of Black citizens with criminal natures. They wrote, “Generalizing against the negro should cease [...] The race should be judged by its best as well as by its worst types. The negro should not be made the universal ‘scapegoat.’ When a crime is committed, the slightest pretext starts the rumor of a ‘negro suspect’ and flaming headlines prejudice the public mind long after the white criminal is found.”64

Conclusion

The juvenile court system in Chicago and nationwide has been subject to consistent criticism and legal attempts to transform it into the reforming entity it initially promised to be. The legitimacy of the court has been questioned on the basis of legal, political, and philosophical grounds, and has continued to struggle against efforts of reform into the 21st century. In 1998, the Illinois Juvenile Justice Reform Act was introduced, advocating for a balanced and restorative justice (BARJ) model for Illinois’ juvenile courts.65 However, this bill proved to be ineffective, as it blended its sentencing options for juvenile cases and adult cases as one, including the ability to transfer juveniles to adult criminal court. Therefore, criticism has persisted as changes failed to be implemented. Public defenders at the time argued that the law would implement an “increasingly punitive response toward all youthful offenders, not merely the ‘super predator’ or ‘serious violent juvenile offender’ whose ‘discovery’ had fueled the current debate.”66 The superpredator theory, now known as the superpredator myth, refers to the idea that there are some juvenile criminals who are willing to commit violent crimes without remorse. This theory was the basis for an increase in “tough-on-crime” legislation that emerged in the 1990s. This legislation continued the trend of courts to further target and criminalize Black Americans, specifically Black youth.

The juvenile court of Chicago at its conception was heavily dominated by racial dynamics and a Progressive sense of moral rectitude. How these institutions defined criminality was heavily based on the intersections of race, gender, and class. While the Progressive Era was a time of rapid urbanization and criminal justice reform, it is essential to understand the factors that went into the development of juvenile justice and how racial attitudes of the time became institutionalized. Throughout the twentieth century, juvenile justice practitioners’ contradictory emphasis on both childhood innocence and an inherent desire for delinquency revealed the racialized definitions in which they categorized poor or at-risk children in the context of differentiating “dependent” or “delinquent.” Race proved to be the defining factor in what type of children Progressive reformists, as well as judges of the juvenile criminal court, thought were worthy of being saved.

Bibliography

Biles, Roger. "Race and Housing in Chicago." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-) 94, no. 1 (2001): 31-38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40193533.

Bowen, Louise de Koven. The Colored People of Chicago: An Investigation Made for the Juvenile Protective Association, by A.P. Drucker, Sophia Boaz, A.L. Harris [and] Miriam Schaffner. Rogers & Hall, 1913.

Chatelain, Marcia. South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration. Duke University Press, 2015.

Charlotte Ashby Crawley, "Dependent Negro Children in Chicago in 1926" (Master's thesis, University of Chicago, 1927); Irene Graham, "Negroes in Chicago, 1920: An Analysis of United States Census Data" (Master's thesis, University of Chicago, 1929.

Commission to Visit and Examine State Institutions, Special Report of Investigation of the Illinois Industrial School for Boys, Sheridan, Illinois (Springfield, Ill.: n.p., 1961).

Desantis, A. “Selling the American Dream Myth to Black Southerners: The Chicago Defender and the Great Migration of 1915–1919,” 1998. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570319809374621.

Dodge, L. Mara. “Our Juvenile Court Has Become More like a Criminal Court": A Century of Reform at the Cook County (Chicago) Juvenile Court.” Michigan Historical Review 26, no. 2 (September 22, 2000): 51–90.

Freedman, Estelle B. Redefining Rape. Harvard University Press, 2013.

Getis, Victoria. The Juvenile Court and the Progressives. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Grossman, James R. Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Jeffrey S Adler. “‘It Is His First Offense. We Might as Well Let Him Go’: Homicide and Criminal Justice in Chicago, 1875-1920.” Journal of Social History 40, no. 1 (2006): 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2006.0067.

“Jessie Binford | Iowa Department of Human Rights,” n.d. https://humanrights.iowa.gov/jessie-binford.

Knupfer, Anne. “African-American Facilities for Dependent and Delinquent Children in Chicago, 1900 to 1920: The Louise Juvenile School and the Amanda Smith School.” The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 24, no. 3 (September 1, 1997). https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol24/iss3/12.

Knupfer, Anne Meis. Reform and Resistance: Gender, Delinquency, and America’s First Juvenile Court. Routledge, 2013.

Odem, Mary. “Delinquent Daughters: Protecting and Policing Adolescent Female Sexuality in the United States, 1885-1920.” University of North Carolina Press. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://uncpress.org/book/9780807845288/delinquent-daughters/.

Pasko, Lisa. “Damaged Daughters: The History of Girls’ Sexuality and the Juvenile Justice System.” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-) 100, no. 3 (2010): 1099–1130.

Ryan, Catherine, Dallas Ingemunson, Amy Maher, and Betsy Clarke. “Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 1998: Balanced and Restorative Justice in Illinois.” National Criminal Justice Reference Service. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=188007.

Scott, Emmett J. “Letters of Negro Migrants of 1916-1918.” The Journal of Negro History 4, no. 3 (July 1, 1919): 290–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/2713780.

Shedd, Carla. Unequal City: Race, Schools, and Perceptions of Injustice. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2015.

Spear, Allan H. Black Chicago: The Making of a Negro Ghetto, 1890-1920. University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Tera Eva Agyepong. The Criminalization of Black Children: Race, Gender, and Delinquency in Chicago’s Juvenile Justice System, 1899–1945. Justice, Power, and Politics. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, University of North Carolina Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469634012_agyepong.

Endnotes

1. L. Mara Dodge, “Our Juvenile Court Has Become More like a Criminal Court": A Century of Reform at the Cook County (Chicago) Juvenile Court,” Michigan Historical Review 26, no. 2 (September 22, 2000): 51–90.

2. Dodge.

3. Tera Eva Agyepong, The Criminalization of Black Children: Race, Gender, and Delinquency in Chicago’s Juvenile Justice System, 1899–1945, Justice, Power, and Politics (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, University of North Carolina Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469634012_agyepong.

4. Tera Eva Agyepong.

5. Tera Eva Agyepong.

6. Tera Eva Agyepong.

7. Agyepong.

8. Agyepong.

9. Dodge, “Our Juvenile Court.”

10. Dodge.

11. Dodge.

12. Dodge.

13. Dodge.

14. Commission to Visit and Examine State Institutions, Special Report of Investigation of the Illinois Industrial School for Boys, Sheridan, Illinois (Springfield, Ill.: n.p., 1961).

15. Anne Meis Knupfer, “African-American Facilities for Dependent and Delinquent Children in Chicago, 1900 to 1920: The Louise Juvenile School and the Amanda Smith School,” Journal of Sociology, n.d., 19.

16. Knupfer.

17. Spear, A. H. (1967). Black Chicago. The making of a Negro ghetto. 1890- 1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

18. A. Desantis, “Selling the American Dream Myth to Black Southerners: The Chicago Defender and the Great Migration of 1915–1919,” 1998, https://doi.org/10.1080/10570319809374621.

19. Desantis.

20. Louise de Koven Bowen, The Colored People of Chicago: An Investigation Made for the Juvenile Protective Association, by A.P. Drucker, Sophia Boaz, A.L. Harris [and] Miriam Schaffner (Rogers & Hall, 1913).

21. Emmett J. Scott, “Letters of Negro Migrants of 1916-1918,” The Journal of Negro History 4, no. 3 (July 1, 1919): 290–340, https://doi.org/10.2307/2713780.

22. Scott.

23. Roger Biles, “Race and Housing in Chicago,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-) 94, no. 1 (2001): 31–38.

24. James R. Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

25. Victoria Getis, The Juvenile Court and the Progressives (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000).

26. Getis.

27. Agyepong, The Criminalization of Black Children.

28. Allan H. Spear, Black Chicago: The Making of a Negro Ghetto, 1890-1920 (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

29. Agyepong, The Criminalization of Black Children.

30. Agyepong.

31. Agyepong.

32. Lisa Pasko, “DAMAGED DAUGHTERS: THE HISTORY OF GIRLS’ SEXUALITY AND THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM,” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-) 100, no. 3 (2010): 1099–1130.

33. Getis, The Juvenile Court and the Progressives.

34. Agyepong, The Criminalization of Black Children.

35. Getis, The Juvenile Court and the Progressives.

36. Charlotte Ashby Crawley, "Dependent Negro Children in Chicago in 1926" (Master's thesis, University of Chicago, 1927); Irene Graham, "Negroes in Chicago, 1920: An Analysis of United States Census Data" (Master's thesis, University of Chicago, 1929.

37. Getis, The Juvenile Court and the Progressives.

38. Dodge, “Our Juvenile Court.”

39. Bowen, The Colored People of Chicago.

40. Knupfer, “African-American Facilities for Dependent and Delinquent Children in Chicago, 1900 to 1920: The Louise Juvenile School and the Amanda Smith School.”

41. Agyepong, The Criminalization of Black Children.

42. Agyepong.

43. Agyepong.

44. Pasko, “DAMAGED DAUGHTERS.”

45. Knupfer, “African-American Facilities for Dependent and Delinquent Children in Chicago, 1900 to 1920: The Louise Juvenile School and the Amanda Smith School.”

46. Mary Odem, “Delinquent Daughters: Protecting and Policing Adolescent Female Sexuality in the United States, 1885-1920,” University of North Carolina Press, accessed December 12, 2020, https://uncpress.org/book/9780807845288/delinquent-daughters/.

47. Louise de Koven Bowen, The Colored People of Chicago: An Investigation Made for the Juvenile Protective Association, by A.P. Drucker, Sophia Boaz, A.L. Harris [and] Miriam Schaffner (Rogers & Hall, 1913).

48. Anne Meis Knupfer, Reform and Resistance: Gender, Delinquency, and America’s First Juvenile Court (Routledge, 2013).

49. Knupfer.

50. Pasko, “DAMAGED DAUGHTERS.”

51. Pasko, “DAMAGED DAUGHTERS.”

52. Pasko, “DAMAGED DAUGHTERS.”

53. Pasko.

54. Pasko.

55. Estelle B. Freedman, Redefining Rape (Harvard University Press, 2013).

56. Freedman.

57. Jane Addams, The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets (Macmillan, 1909).

58. Getis, The Juvenile Court and the Progressives.

59. Bowen, The Colored People of Chicago.

60. Dodge, “Our Juvenile Court.”

61. L. Mara Dodge, “Our Juvenile Court Has Become More like a Criminal Court": A Century of Reform at the Cook County (Chicago) Juvenile Court,” Michigan Historical Review 26, no. 2 (September 22, 2000): 51–90.

62. Dodge, “Our Juvenile Court.”

63. Bowen, The Colored People of Chicago.

64. Bowen.

65. Catherine Ryan et al., “Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 1998: Balanced and Restorative Justice in Illinois,” National Criminal Justice Reference Service, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=188007.

66. Tera Eva Agyepong, The Criminalization of Black Children: Race, Gender, and Delinquency in Chicago’s Juvenile Justice System, 1899–1945, Justice, Power, and Politics (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, University of North Carolina Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469634012_agyepong.