By Alexandra Tamvakis

Edited by Leila Iskandarani '22 and Philip Mousavizadeh '24

Introduction

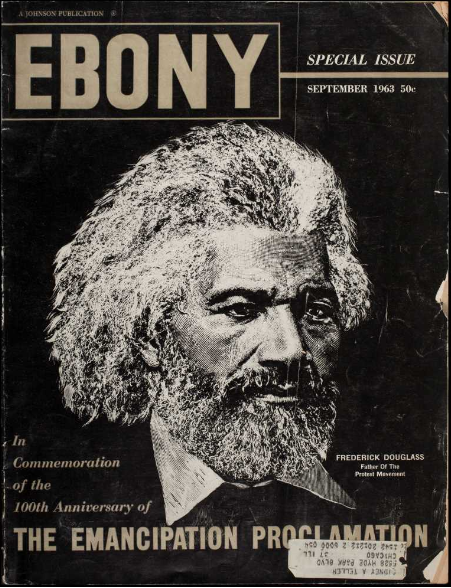

On August 16, 1963, a few thousand visitors streamed through the doors of McCormick Place, a convention hall located near Lake Michigan in Chicago, Illinois. As they entered the exhibition hall, they were greeted by a replica of an African village, including huts and a waterfall. Farther down the hall, the visitors looked upon numerous exhibits designed to tell the story of Black Americans' achievements since the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation.1 The exposition, entitled "A Century of Negro Progress," was organized by the American Negro Emancipation Centennial Authority (ANECA) and was intended to commemorate the centennial of the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation. The exposition ran for 18 days, each of which was organized around a unique theme such as Fine Arts, Women, Sports, and Education. It featured a display of the only surviving copy of the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, twice-daily performances of Duke Ellington's "My People"—a production created exclusively for the event—as well as a variety of exhibits designed to inform viewers of the accomplishments made by Black Americans within the past century.2

During the lead up to the exposition, the event received coverage in newspapers across the nation, bolstered by the federal government's support as President Kennedy authorized a commemorative postage stamp to be issued at the event. The exposition's executive director, Alton A. Davis, predicted the number of visitors to be close to a million people, with notable visitors such as Martin Luther King, Jr. attending.3

However, before the exposition came to a close on September 2, it was evident that it had not lived up to expectations. After thirteen days, only 73,000 people had visited the exposition—even though the event's organizers had lowered the price of children's admission midway through the exposition. There were rumors that the event would close early, which Alton Davis strongly refuted, stating that "We will not close before Sept. 2."4 The content of the exposition was berated by the media, with critics pointing out the multitude of spelling errors present in many of the exhibits. Additionally, critics pointed out the lack of entertainment afforded by the exhibits. As a writer for the New Pittsburgh Courier summarized, "The show is largely one of pictures and other illustrations. Very little by way of dynamic, live exhibits can be found on the massive exhibition floor of McCormick Place…An unusual number of spelling and factual errors have also drawn comment from persons who have examined the exhibits with care. The appearance is that some of the exhibits were produced with little research and less editing."5 In all, the "Century of Negro Progress" exposition can be characterized as a failure, albeit one with noble intentions.

In many ways, the "Century of Negro Progress" exposition illustrates the commemoration of the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation as a whole. Like the Emancipation centennial, the event was a highly anticipated collaborative effort between nonprofit groups, local leaders, and the federal government, and placed considerable emphasis on Black American history and education.

Furthermore, like the centennial, the exposition failed to meet expectations, drew a lukewarm reception, and did not receive extensive scholarly attention in subsequent decades. The lack of widespread commemoration of the Emancipation centennial can be attributed, at least in part, to the sociopolitical milieu of the 1960s. As one Variety magazine writer asserted, "It is the almost unanimous (albeit hindsight) conclusion of both Negro and white observers that the Negro community is in no mood for retrospection, and the current racial stance is one of militancy for the present and ferment for the future."6

Background: The 1960s

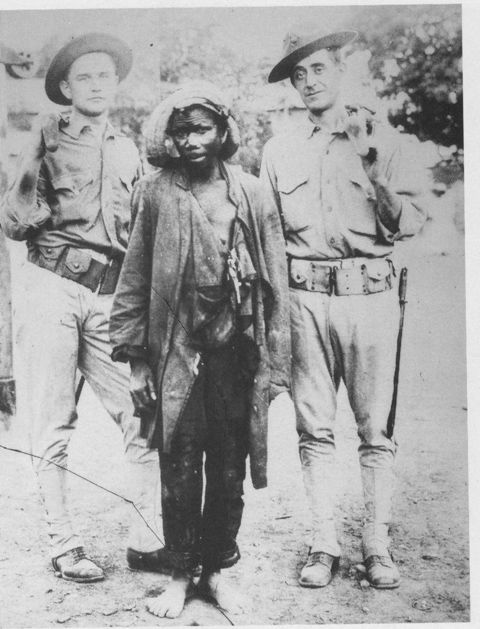

In order to conceptualize the varied responses of Americans—Black Americans, in particular—to the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, it is necessary to examine the broader historical context into which the centennial can be placed. The decade of the 1960s has often been characterized as a watershed moment in American history, for good reason; the period saw extensive changes in the fabric of American society. Although the tensions of the Cold War with Russia were ever rising, Americans felt intense pressure at home as Black Americans fought segregation and racism.

While the civil rights movement has roots dating back to the abolition movement and the Reconstruction era of the nineteenth century, many point to the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education as the start of the civil rights movement. The 1954 Brown decision struck down the constitutionality of racial segregation in public schools, although many schools effectively remained segregated for years after the fact. The following year, Black Americans in Montgomery, Alabama began protesting segregation on the city's public transit system with a bus boycott. The boycott, in which Black women played a particularly significant role, marked one of the first major acts of protest against segregation in the United States.

Subsequent years saw increasing levels of activism by Black Americans. In 1960, four Black university students in Greensboro, North Carolina sparked a wave of protests after engaging in a sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter. Across the South, college students became increasingly important in the fight for civil rights. The following year saw the beginning of the "Freedom Rides", a series of organized bus trips to test federal enforcement of Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia and Boynton v. Virginia, which, in theory, ended segregation in interstate travel including on public buses and in terminals. The Freedom Rides were met with extreme violence throughout the South and received extensive media coverage across the United States.

The 1960s also bore witness to the escalation of the Cold War. For instance, in 1961, just one year after President John F. Kennedy’s election, the CIA-supported Bay of Pigs invasion failed dramatically, casting a negative light on the Kennedy administration. The operation was intended to overthrow Fidel Castro, who was the Cuban Prime Minister and leader of the Communist Party of Cuba, as well as an important ally to the Soviet Union. Only one year later, the world watched anxiously as the United States veered dangerously to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R. as the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolded. Beyond the conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union over nuclear arms, the Cold War represented a clash in ideology, with the American government vehemently rejecting the communist ideals of the Soviet Union. For this reason, much of the leading American culture at the time emphasized unity, patriotism, and consensus.

1963: The Emancipation Centennial

The year 1963 was particularly monumental, both for the civil rights movement and for the United States in its entirety. It was the year that Alabama Governor George Wallace declared “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever” in his inaugural speech; the year that Martin Luther King, Jr. penned his Letter from Birmingham Jail; the year that Medgar Evers was assassinated; the year that multiple countries signed a nuclear test ban treaty; the year that the March on Washington took place; and the year that John F. Kennedy was assassinated. In addition to these events, the year 1963 also marked the 100th anniversary of the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation.

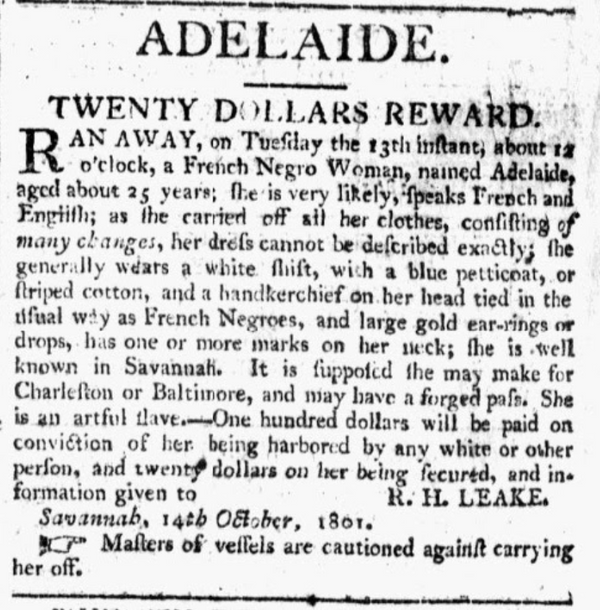

The Emancipation Proclamation—which was issued in late 1862 by President Abraham Lincoln and went into effect on January 1st, 1863—had an immeasurable impact on the course of American history. Under the Proclamation, all enslaved people in locations "in rebellion against the United States" were free. In some ways, however, the Proclamation fell short of its lofty intentions. The Proclamation freed the enslaved people of the South—a region that did not recognize Lincoln's sovereignty and thus did not heed the Proclamation's directive. Still, as the Union army made its way throughout the South, it freed the enslaved people that it encountered, with many formerly enslaved people electing to join the Union army's cause. In addition, the Proclamation took no effect in the border states, as they were not raised in rebellion against the United States. Regardless of the Proclamation’s immediate impact (or lack thereof), Lincoln’s issuance of the document affirmed the United States government’s support of abolition. As a writer for Ebony Magazine described the Proclamation one hundred years later:

The paper he signed was a curious document; it was as dry as a brief in a real estate case. Nor did the proclamation do much emancipating. Lincoln freed Negroes where he had no power (in the Confederacy) and left them slaves where he had power (in the loyal Border states and in sections under federal control in the South). Still, there was something about the piece of paper. Despite its many exceptions, despite its repeated pleas of "military necessity," despite its matter-of-fact dryness, the documents became one of the great state papers of the century. And it converted a vague war for Union into something men could get their teeth into: a war for freedom.7

The Civil War Centennial

The commemoration of the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation was part of a broader commemoration of the Civil War Centennial, which lasted from 1961 to 1965. The centennial commemoration was spurred in part by Congress' passage of an act to create the United States Civil War Centennial Commission in 1957. The Commission, often referred to as the CWCC, oversaw the federal government's Civil War centennial observances as well as those of the state chapters. The Commission was controlled by white Southerners and segregationists—in general, the Southern states tended to take a more active role in planning and observing the centennial as the majority of Civil War sites can be found in the South, and some states saw the centennial as a means of boosting tourism revenue.8 As a writer for the Baltimore Afro-American asserted, “The Centennial Commission seems dominated by Southerners who like to paint pictures of slaves faithfully caring for the old Southern homestead while the man of the family was away at war.”9

Early leaders of the CWCC emphasized military history and war reenactments, intentionally aiming to avoid controversial issues in its observances. As historian and commission member Bell Wiley made clear during the CWCC’s first national assembly in 1958, the Commission had no intent of encouraging division: "Rather, we want to commemorate the greatness demonstrated by both sides in that momentous struggle. The Civil War was a time of supreme greatness for both North and South—and for the American nation."10 Although the Commission likely had a number of justifications for avoiding ostensibly controversial issues, the CWCC’s emphasis on unity and American superiority can be best understood within the context of the Cold War with Russia. As Senator Joseph O’Mahoney asserted during the formation of the Commission, “The purpose of the observance of this great schism between our people is not to stress that which divides us but rather to reaffirm that which united us—the basic desire for unity, liberty, freedom, and self-government...and how out of that crisis was forged the unity of this country which is so much the envy and, it is hoped, the ideal of the rest of the world.”11 The United States government and the Commission aimed to use the centennial as a means of championing the country’s democratic values and unity, not as an opportunity to reconcile with the nation’s history of slavery and racism.

It was not long before the Commission ran into controversy, however. In 1961, the CWCC held its fourth national assembly in Charleston, South Carolina. Among the prospective attendees was Mrs. Madeline Williams, a member of the New Jersey Civil War Centennial Commission. Williams, a Black woman, was denied hotel accommodations due to the segregated nature of the assembly's location. The controversy reached President Kennedy, who, only a few months into his term, took a stance in favor of civil rights. Kennedy instructed the Commission to accommodate Mrs. Williams, and alternative housing was found.12 One news article summed up the situation by writing “The Southerners had first tried to repel a ‘Yankee invasion’ by setting up a segregated centennial commemoration in a jimcrow [sic] hotel. This strategy was outflanked by President Kennedy who ordered that it be held in Union territory—the Charleston Navy Yard.”13

President Kennedy took another stance in favor of the civil rights movement in February 1963, when the White House hosted a reception to celebrate Abraham Lincoln's birthday as well as the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. The reception was attended by over 800 civil rights leaders, with some estimates ranging to over 1,000. The event was intended to be bipartisan and aimed to bring individuals of all races together, with some media outlets reporting that the majority of the attendees were Black. Notable attendees included Federal Judge Thurgood Marshall and Executive Secretary of the NAACP Roy Wilkins, as well as musicians Sammy Davis Jr. and Lionel Hampton. Before the event, President Kennedy was presented with a report on civil rights developments of the last hundred years, prepared by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission.14

More than the Civil War Centennial Commission, President Kennedy grasped the significance of the Emancipation centennial to the contemporary fight for civil rights. As he wrote for Ebony Magazine's Centennial Issue:

I believe that future historians, looking back on the brave events of recent months, will regard the year 1963 as the beginning of the final stage—as the great turning-point, when the nation at last undertook to carry the process of emancipation through to its fulfillment. After a century of evasion and delay, the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation is at last on the verge of realization.15

The Civil War and Emancipation centennials were observed and celebrated by more than just the aforementioned government entities, however. Black Americans commemorated—or chose not to commemorate—the Emancipation centennial in a variety of ways and from a variety of viewpoints. The diverse responses to the commemoration of the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation are representative of the numerous attitudes, priorities, and objectives of Black Americans at the time.

A Celebration of Black History

A number of groups and individuals used the centennial as an opportunity to celebrate and teach Black history. In letters sent out to branches, youth councils, and college chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the organization encouraged commemoration of the centennial in different ways. In one such letter, the NAACP advised chapter leaders to reach out to schools, colleges, libraries and history museums to sponsor exhibits on Black history:

Ask public schools, colleges, libraries, historical museums to sponsor exhibits. Many libraries and museums in your city have memorabilia about the Civil War in its aftermath and and about Negro progress locally which could be included...Consideration will be given, upon request, for the loan of material in the custody of the National Archives, to groups planning displays throughout the United States.16

In addition, the NAACP encouraged chapters to request that local libraries display books on Black history, race relations and civil rights, and advised youth councils and college chapters to present “pageants and plays depicting 100 years of progress.”17

Educational institutions also played a significant role in commemorating the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, often by discussing Black history. In New York City, The New School for Social Research held a lecture series beginning in October 1962 and lasting until January 1963. The president of The New School, Dr. Henry David, detailed the intent of the lecture series, stating that “The distinguished participants in this series not only will ask ‘What has happened in the one hundred years since Emancipation?’, but also ‘Where do we stand today?’ and ‘Where do we go from here?’ I think that this is the spirit in which Americans should mark this important anniversary.”18 The lecture series primarily featured speakers from academic backgrounds, as well as some government employees. Topics discussed in the lecture series included “The Impact of the Emancipation Proclamation” and “Emancipation and the White South.” The New School’s lecture series connected discussions of history and sociology with current issues, with the final lecture of the series being “Emancipation: Promise and Fulfillment.”19

The emphasis on history was not restricted to higher education. In some grade schools, teachers made an effort to teach students about the accomplishments of Black Americans from the last hundred years and earlier. School officials in the Chicago public school system were encouraged by the superintendent of schools to hold assemblies, develop programs, and create classroom activities to commemorate the centennial.20 In Norfolk, Virginia, Bowling Park Elementary School commemorated Black history under the theme “We Celebrate 100 Years of Progress.”21 Students at the school examined Black history from local, national, and international perspectives, with each grade collaborating on an activity or exhibit.

Black American history and Black historical memory played an integral role in Black communities during this time period. While Black Americans were facing extreme levels of injustice and institutionalized racism throughout the nation, Black history served as a point of solidarity and pride. As historian Jennifer Waldkirch asserts, “Many black historians of the era viewed the spread of African American history as vital to the spread of racial pride and civic unity, teaching Americans of all races to see the humanity and value of black individuals and their communities.”22 While the use of historical memory in the fight for civil rights will be examined in further detail, it is important to note the presence of the study of Black history for purposes of unity and connection in Black communities. The Emancipation centennial provided a prime opportunity for Black Americans to reflect upon their shared history.

Community Gatherings and Observances

Beyond educational institutions, community organizations and religious groups held gatherings intended to commemorate the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. Although it was not necessarily the focus of these events, such community gatherings often highlighted the history and achievements of Black Americans. At the least, almost all gatherings and celebrations included a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation itself. Such gatherings ranged in size, and were held by communities throughout the United States—from metropolitan to rural areas. In contrast to the events held by the CWCC, events held by Black American communities can generally be described as more community-oriented, and were often centered around places

of worship. This is unsurprising, as religious centers served as community meeting places for many Black Americans.

In Raleigh, North Carolina, the celebration of the centennial was held at the First Baptist Church on January 6, 1963. The event included speeches by people from a number of backgrounds, including educators and religious leaders. Along with the speeches, the program included a prayer and multiple choir performances. In addition, a local public school student read the Emancipation Proclamation.23

In New York City, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church commemorated the centennial with a four-day celebration in September 1963. The commemorative event was particularly celebratory: it began with a parade, included multiple days of “pageantry and music” and ended with a banquet. While the event may have struck a more jubilant tone, it did not neglect the historical roots of the commemoration and included "several days of addresses exploring the history, meaning and responsibilities of our freedom."24

Community gatherings ranged in size and tone, but could be found across the United States. Such gatherings gave communities the opportunity to celebrate and commemorate the progress made in the past hundred years, and, in some cases, the chance to discuss the relationship between historical events and current issues.

Historical Memory and the Fight for Civil Rights

As some Black Americans seized the opportunity provided by the centennial to teach Black history and celebrate with their communities, the fight for civil rights proceeded. Civil rights leaders interpreted the Emancipation centennial in various ways. Some saw the centennial commemoration as a means of using historical memory as a motivating factor for social change. Martin Luther King, Jr. was particularly aware of the significance of the centennial and often used it to the advantage of civil rights activists. He repeatedly drew parallels between Lincoln’s federal intervention in freeing the enslaved people in the Confederate states and potential federal intervention to end segregation. In May 1962, Martin Luther King, Jr. directly called upon the federal government to intervene and end segregation in the United States in an open letter, "Appeal to the Honorable John F. Kennedy, President of the United States, for a National Rededication to the Principles of the Emancipation Proclamation and for an Executive Order Prohibiting Segregation in the United States of America."25

In the letter, King highlights historical memory, writing, "The struggle for freedom, Mr. President, of which the Civil War was but a bloody chapter, continues throughout our land today. The courage and heroism of Negro citizens at Montgomery, Little Rock, New Orleans, Prince Edward County, and Jackson, Mississippi is only a further effort to affirm the democratic heritage so painfully won, in part, upon the grassy battlefields of Antietam, Lookout Mountain, and Gettysburg."26 By drawing parallels between Americans fighting for freedom in the Civil War and those fighting for freedom in the civil rights movement, King hoped that he would spur Kennedy to action. However, Kennedy did not respond to such appeals for what some referred to as a second Emancipation Proclamation.This lack of a response can perhaps be attributed, at least in part, to Kennedy’s fear of alienating Southern Democrats in the lead up to the 1962 midterm elections.27

King continued to make use of historical memory in relation to the Emancipation Proclamation in his activism and speeches. In what can be considered his most famous speech of all time, which was given from the shadow of the Great Emancipator—on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial—King invoked the promises of the Proclamation. The speech, most often referred to as his "I Have a Dream" speech, was given at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963, the year of the Emancipation centennial. Throughout the speech, King maintains the connection to the Emancipation Proclamation in his oration:

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice...But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.28

While this speech is most often remembered for King’s powerful “I have a dream” refrain, it serves as an exceptional example of the way in which historical memory was used to strengthen the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was certainly not alone in his use of historical memory in the fight for civil rights. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, aside from the aforementioned efforts to celebrate Black history, also used the memory of the Emancipation Proclamation as a strategy to earn support for their cause. In 1963, Gloster B. Current—the Director of Branches at the time—sent a memorandum to the larger chapters of the NAACP informing them of the year's poster design. The poster, which depicted a statue of Abraham Lincoln with the words "..thenceforward and forever free," "Let's finish the job now," and "Join NAACP," was to be pasted on billboards, used in membership drives, and displayed in the subways of New York City.

Like Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech from the March on Washington, the NAACP poster combined historical memory with the fight for civil rights. By recalling words and iconography from the Emancipation Proclamation, civil rights leaders aimed to gain support and motivate supporters to action in the fight against segregation and racism.

Rejection of Commemoration

Naturally, reactions to the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation varied—not everyone embraced the commemoration. Some Black Americans rejected the celebration of the Emancipation centennial, be it for ideological reasons or particular issues with specific events. In Washington, D.C., a centennial observance was held at the Lincoln Memorial on September 22, 1962, the 100th anniversary of the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. The celebration was planned by the Civil War Centennial Commission, among others. Bishop Smallwood E. Williams, the president of the Washington, D.C. branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, began a boycott of the centennial observance. As Williams asserted, the observance was planned without the consultation of Black leaders and featured no Black speakers as part of the program—a “mockery.” The boycott was endorsed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., aiding in its efficacy.30

Soon after the boycott began, the CWCC began consulting with Black leaders. Although the consultation initially suffered from some delays, it was ultimately effective: the CWCC added Federal Judge Thurgood Marshall to the program as a speaker and Bishop Williams withdrew the boycott. While Williams encouraged others to attend the event, he stood by his principles, stating, “If our approach to the goal of full citizenship at times seems uncourteous and embarrassing one has only to reflect upon the condition the Negro finds himself in today.”31

Although the boycott was withdrawn, the observance failed to meet expectations. The event’s attendance was considered lackluster, with only 3,000 people attending—and fewer than 600 Black attendees.32

Some civil rights leaders rejected the celebration of the Emancipation centennial as a whole. Julius W. Hobson, the chairman of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, publicly opposed the celebration of the centennial. He stated that he could not "in good conscience" celebrate the Emancipation centennial because "I and no other Negro have ever enjoyed it." Hobson asserted that he felt that he would be "doing the Negro people in this country a grave injustice if, under the present circumstances, I joined in any kind of victory celebration on the still too-long road to freedom."33

Hobson was not alone in his thinking. Other activists communicated support of his statements, while still others expressed similar opinions. Among them was Kenneth B. Clark, a Black psychologist whose work included the prominent "doll test" which explored the impact of racial segregation on children. His research was an important part of the Brown v. Board of Education case nearly a decade before the Emancipation centennial. Writing for Ebony magazine's centennial edition, Clark stated, “Rather than indulging in the traditional rituals—oratory, parades, pomp and ceremonials—for celebrating such important anniversaries, American Negroes...are celebrating this centennial with a desperate push to finish the unfinished business of obtaining their full and unqualified rights as American citizens.”34

Conclusion

The ways in which Black Americans commemorated or chose not to commemorate the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation give insight into the diverse attitudes and priorities of Black Americans at the time. In the words of Jennifer Waldkirch, “Many black activists in this era did not fall neatly into a philosophical category and neither did their beliefs about the past.”35 This principle can be applied more broadly: Black Americans are not a monolith, and different groups and individuals responded in different ways to the observance of the centennial.

For a number of educational institutions, community organizations, and religious congregations, the centennial presented an opportunity to celebrate the progress made by Black Americans in the preceding hundred years. Community observances and celebrations drastically

ranged in size, from small celebrations in rural Southern counties to large, multi-day events in major metropolitan areas. Community gatherings also ranged in tone; while some observances struck a more solemn, contemplative tone, others were jubilant, celebratory affairs. Community observances often referenced history, and most included readings of the Emancipation Proclamation. In addition to providing an opportunity for celebration and remembrance, community observances of the Emancipation centennial gave communities a chance to gather in a unified manner during a time fraught with conflict and division.

Across the United States, groups and individuals seized the opportunity provided by the centennial to educate others about Black history. From college lecture series to grade school exhibits, Americans—particularly Black Americans—examined and discussed Black history in an unprecedented manner. Discussions of Black history provided a sense of unity and cultural pride in Black communities, particularly in the face of the socio-political issues Black Americans faced at the time. While the United States was rife with racism, from segregation to cultural attitudes, studying Black history allowed Black Americans to celebrate the accomplishments made and obstacles overcome thus far.

Black history and historical memory served another crucial purpose as a tool in the fight for civil rights. Civil rights leaders used the historical memory of slavery and emancipation to impact supporters and call upon leaders for change. Of the civil rights leaders who employed this strategy, it is perhaps Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who utilized it most skillfully. King repeatedly drew parallels between the federal intervention of the Emancipation Proclamation and potential federal intervention to end segregation. Although these appeals generally went unanswered by the Kennedy administration, King’s rhetoric was no less powerful. In some of his most impactful speeches, King connected the plight of Black Americans during slavery to the plight of Black Americans under segregation and institutionalized racism.

However, even as some civil rights leaders embraced historical memory and commemorative attitudes during the Emancipation centennial, others firmly rejected them. Some civil rights leaders viewed the celebration of the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation as a disservice to Black Americans, who were still facing extreme levels of inequality. As civil rights activist Grant Reynolds described one of the Kennedy administration’s commemorative events, “This Emancipation-civil-rights-party is typical of the Kennedy’s whole civil rights program, a program of big talk and little action.”36

While it would be misleading to state that the Emancipation centennial was insignificant, it is true that it was not observed by the majority of Americans. Of the events of 1963, few people—if any—would consider the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation to be the most impactful or memorable. By some measures, the centennial fell short of expectations, with numerous commemorative events suffering from low attendance and lackluster receptions. Indeed, the Emancipation centennial did not receive the response that it seemed to deserve. The issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation—one of the most significant moments in the Civil War and American history in its entirety—could have been the heart of the Civil War centennial. However, the socio-political conflicts of the 1960s can account for the diminished response to the commemoration, at least in part. As the country continued to deny Black Americans equality in numerous aspects of life, it is unsurprising that many Black Americans did not feel inclined to celebrate abstract ideas of freedom and democracy.

Nevertheless, the Emancipation centennial was observed and commemorated by Black Americans and impacted contemporary discussions of Black history and civil rights. While the sweeping federal intervention imagined by some civil rights activists—akin to a second Emancipation Proclamation—never came to fruition, the centennial provided opportunities for the Kennedy administration to ally itself with the civil rights movement on multiple occasions, such as during the early CWCC fiasco and the White House centennial reception. Further, the Emancipation centennial served as a reference point in the rhetoric of civil rights leaders.

It is impossible to quantify or measure the extent to which historical memory and the Emancipation centennial impacted the civil rights movement. Ultimately, the progress made during the civil rights movement can be attributed to the tireless efforts of civil rights activists and Black Americans, who were perhaps bolstered by historical memory and discussions of the Emancipation Proclamation centennial.

Bibliography

"100 Yrs. of Progress, but Not in Spelling." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Aug 21, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/493977677.

"Accent on Negro History." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-2001), Apr 02, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/532302733.

"'A Century of Negro Progress' Exposition: Complete Program August 16 -- September 2." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Aug 15, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/493978346.

"AME Zion Church to Mark Emancipation Centennial." Afro-American (1893-1988), Jul 20, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/532236296.

"Big Emancipation Edition on Jan. 24." Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005), Jan 03, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/564672263.

Blight, David W.. American Oracle: Commemorating the Civil War in the Civil Rights Era. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011.

Buckley, Thomas. "Dr. King Decries Civil Rights Pace: Prods U.S. in Speech Here at Emancipation Fete." New York Times (1923-Current File), Sep 13, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/115771693.

"'Century of Negro Progress' Expo in Chi Flops; Out of Tune with Racial Issues." Variety (Archive: 1905-2000), Sep 04, 1963, 1-1, 62. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/1017107487.

"City to Participate in Negro Century of Progress Exposition." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Jun 13, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/493972039.

Clark, Kenneth B.. “A Relevant Celebration of the Emancipation Centennial,” Ebony Magazine, September 1963, 23. University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

"Cleric Asks Mahalia Jackson to Boycott Emancipation Fete." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Sep 18, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/493914760.

Cook, Robert J..Troubled Commemoration: The American Civil War Centennial, 1961-1965. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.

Dawson, Horace, Jr. "Observance is Target of Historians." Afro-American (1893-1988), Oct 21, 1961. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/532078851.

Day, Dan. "800 Civil Rights Leaders Attend Pres. Kennedy's Emancipation Reception: New Frontier Fete Steals GOP Lincoln's Day Thunder." Call and Post (1962-1982), Feb 23, 1963, City edition. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/184435518.

Day, Dan. "Emancipation Program Attracts Only 3,000." Afro-American (1893-1988), Sep 29, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/532101209.

"D.C. Schools Plan Greater Emphasis on Negro History." Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), Jan 31, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/491276056.

"Dr. King Tours Chi Exposition." Afro-American (1893-1988), Aug 31, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/532055490.

Emancipation Proclamation Centennial observances by NAACP branches, Jan 01, 1962 - Dec 31, 1963, Group III, Series A, Administrative File, General Office File, Papers of the NAACP, Part 24: Special Subjects, 1956-1965, Series C: Life Memberships-Zangrando, Library of Congress. https://congressional.proquest.com/histvault?q=001487-017-0668.

"GOPer Rips White House on Centennial Dinner." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Feb 11, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/493961539.

Kennedy, John F.. Ebony Magazine, September 1963, 20. University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections. http://www.aac.amdigital.co.uk.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/Documents/Images/UIC_BHC_0001 _0001/0.

King, Martin L., Jr. “I Have a Dream.” Speech presented at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/i-have-dream-address-delivered march-washington-jobs-and-freedom.

"Lecture Series to Mark Emancipation Centennial." New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993), Oct 13, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/226761597.

"Millions Celebrating Emancipation Centennial: Progress Hailed." Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005), Jan 31, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/564665981.

“NAACP Raps Slow Pace of Integration.” The Minneapolis Morning Tribune (1939-1964), Jun 30, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/1861339973.

"NAACP Set to Celebrate Emancipation Centennial." Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), Dec 23, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/491270843.

"Negro Exhibit to Start 18-Day Run Tomorrow." Chicago Tribune (1963-1996), Aug 15, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/182794362.

"Negro History Observance Set at School." New Journal and Guide (1916-2003), Feb 02, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/568788362.

“Negroes’ Boycott in Capital Stands: Emancipation Observance Saturday Left Unsettled." New York Times (1923-Current File), Sep 18, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/116192924.

"Negroes Withdraw Opposition to Centennial Fete." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Sep 20, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/141723203.

"Never Freed, CORE Leader Says in Accepting Emancipation Bid," Call and Post (1962-1982), Dec 22, 1962, City edition. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/184347574.

"Partial Text of Kennedy's Message to Congress on Civil Rights." The Sun (1837-1994), Mar 01, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/534072214.

"Pitt County to Observe Emancipation Centennial." New Journal and Guide (1916-2003), Dec 29, 1962. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/568634837.

"President Greets Guests at White House Reception." New Journal and Guide (1916-2003), Feb 23, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/568793937.

"Schools to Observe Emancipation Fetes." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Jan 21, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/493947884.

Schreiber, George. "Exposition Tells Progress of Negroes in America." Chicago Tribune (1963-1996), Aug 17, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/182793691.

Shields, Del. "Taking Care of Business: Bad Timing to Blame for Exposition Shame." Philadelphia Tribune (1912-2001), Sep 17, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/532300800.

"Story that Dixie Refuses to Tell." Afro-American (1893-1988), Apr 22, 1961. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/532036019.

“Ten Most Dramatic Events in Negro History,” Ebony Magazine, September 1963, 32. University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

"The Topic was "Freedom"." New Journal and Guide (1916-2003), Jan 12, 1963. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/568798405.

Waldkirch, Jennifer Caroline. "Black Historical Memory of Slavery and Emancipation in the Activism and Politics of the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Late Pan-African Movements, 1960-1988." Order No. 27814864, North Carolina State University, 2019. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/2396684783.

"What Courier Readers Think: Calls Emancipation Current Hoax." Pittsburgh Courier (1955-1966), Feb 09, 1963, City Edition. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/202523497.

Wiggins, William H., Jr. ""Lift Every Voice": A Study of Afro-American Emancipation Celebrations." Journal of Asian and African Studies 9, no. - (07, 1974): 180-191. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/60862928.

Wood, Sam. "$50,000 Attendance: Crowds at Century Expo Disappointed Over Exhibitions." New Pittsburgh Courier (1959-1965), Sep 14, 1963, National edition. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/doc view/371580928.

Image Credits

Figure 1 : Emancipation Proclamation Centennial observances by NAACP branches; Jan 01, 1962 - Dec 31, 1963; Group III, Series A, Administrative File, General Office File; Papers of the NAACP, Part 24: Special Subjects, 1956-1965, Series C: Life Memberships-Zangrando; Library of Congress.

Endnotes

- George Schreiber, "Exposition Tells Progress of Negroes in America." Chicago Tribune (1963-1996), Aug 17, 1963.

- "'A Century of Negro Progress' Exposition: Complete Program August 16 -- September 2." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Aug 15, 1963.

- "Negro Exhibit to Start 18-Day Run Tomorrow." Chicago Tribune (1963-1996), Aug 15, 1963.

- Sam Wood, "$50,000 Attendance: Crowds at Century Expo Disappointed Over Exhibitions." New Pittsburgh Courier (1959-1965), Sep 14, 1963, National edition.

- Wood, “$50,000 Attendance.”

- "Century of Negro Progress' Expo in Chi Flops; Out of Tune with Racial Issues." Variety (Archive: 1905-2000), Sep 04, 1963, 1-1, 62.

- Ten Most Dramatic Events in Negro History,” Ebony Magazine, September 1963, 32. University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

- David W. Blight, American Oracle: Commemorating the Civil War in the Civil Rights Era (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011), 11.

- "Story that Dixie Refuses to Tell." Afro-American (1893-1988), Apr 22, 1961.

- Robert J. Cook, Troubled Commemoration: The American Civil War Centennial, 1961-1965 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007), 62.

- Ibid, 29-30.

- Ibid, 88-107.

- "Story that Dixie Refuses to Tell."

- Dan Day, "800 Civil Rights Leaders Attend Pres. Kennedy's Emancipation Reception: New Frontier Fete Steals GOP Lincoln's Day Thunder." Call and Post (1962-1982), Feb 23, 1963, City edition.

- John F. Kennedy, Ebony Magazine, September 1963, 20. University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

- Emancipation Proclamation Centennial observances by NAACP branches; Jan 01, 1962 - Dec 31, 1963; Group III, Series A, Administrative File, General Office File; Papers of the NAACP, Part 24: Special Subjects, 1956-1965, Series C: Life Memberships-Zangrando; Library of Congress.

- Ibid.

- "Lecture Series to Mark Emancipation Centennial." New York Amsterdam News (1962-1993), Oct 13, 1962.

- Ibid.

- "Schools to Observe Emancipation Fetes." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Jan 21, 1963.

- "Negro History Observance Set at School." New Journal and Guide (1916-2003), Feb 02, 1963.

- Jennifer Caroline Waldkirch, "Black Historical Memory of Slavery and Emancipation in the Activism and Politics of the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Late Pan-African Movements, 1960-1988." Order No. 27814864, North Carolina State University, 2019, 5.

- Emancipation Proclamation Centennial observances by NAACP branches; Jan 01, 1962 - Dec 31, 1963.

- "AME Zion Church to Mark Emancipation Centennial." Afro-American (1893-1988), Jul 20, 1963.

- Cook, Troubled Commemoration, 186.

- Ibid, 187.

- Blight, American Oracle, 18.

- Martin L. King, “I Have a Dream.” Speech presented at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963.

- “Negroes’ Boycott in Capital Stands: Emancipation Observance Saturday Left Unsettled," New York Times (1923-Current File), Sep 18, 1962.

- "Negroes Withdraw Opposition to Centennial Fete," The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Sep 20, 1962.

- Dan Day, "Emancipation Program Attracts Only 3,000" Afro-American (1893-1988), Sep 29, 1962.

- "Never Freed, CORE Leader Says in Accepting Emancipation Bid," Call and Post (1962-1982), Dec 22, 1962, City edition.

- Kenneth B. Clark, “A Relevant Celebration of the Emancipation Centennial,” Ebony Magazine, September 1963, 23. University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

- Waldkirch, "Black Historical Memory of Slavery and Emancipation in the Activism and Politics of the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Late Pan-African Movements, 1960-1988," 7.

- "GOPer Rips White House on Centennial Dinner." Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Feb 11, 1963.