By Chinaza Asiegbu

Originally published in July 2021 as part of Intersections, a joint issue of The Northwestern Undergraduate Research Journal (NURJ) and the YHR.

Introduction

Since 1921, the Miss America pageant had been cherished as the pride of American beauty and womanhood—but this was not the case in the year of 1968. From black people’s perspective, the pageant was yet another representation of the discrimination that refused to acknowledge black women as participants of the American tradition. In fact, the first African American contestant in the Miss America Pageant would not grace the stage until 1970.1 During the Tumultuous Sixties, a watershed period for social justice movements, the youth were challenging widely accepted American traditions and rupturing the status quo. Trading in Boardwalk Hall for the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Atlantic City, black community organizers led the fight for recognition and inclusion by creating a new pageant: Miss Black America. On the Atlantic City Boardwalk, a slew of white Women’s Liberation protesters assembled in front of the Convention Center to fight for revolution and transformation. Yet, on the front lines, there stood two black women: Bonnie Allen, a “negro housewife from the Bronx” 2 and Florynce Kennedy, “an African American lawyer, feminist, and civil rights activist noted for defending Black Power radicals and instigating inventive political protests.” 3 Staring down judgement from black and white activists of both protests, Kennedy chained herself to a grand cardboard effigy that was fashioned to sport blonde hair, pale skin, satirically long eyelashes, and a red, white, and blue bathing suit with gold stars over the breasts.

During the Miss America Protests of 1968, in choosing to stand with the predominately white Women’s Liberation Movement rather than standing with her black brothers and sisters in the formation of the first Miss Black America pageant, Kennedy may initially seem like she is turning her back on the Black Pride movement. However, the crucial role Kennedy played in both the feminist and civil rights movements sings an entirely different tune, demonstrating not an allegiance to one facet of her identity and betrayal to another but instead an innovative flexibility that allowed Kennedy to unify the oppressions faced by those at the intersection of racism and sexism in the United States.4 Her influence expanded beyond bridging movements to bridging stratifications within communities, such as in the case of Atlantic City. As a fervent activist in civil rights, consumer rights, black nationalism, and second-wave feminism, Kennedy galvanized people to expand their approach to oppression beyond their respective marginalized groups to broader, more collaborative ranges of radical activism. In a society that struggled to comprehend the potential for collaboration and instead pitched movements against each other, Kennedy’s involvement illustrated how these movements did not necessarily have to compete for the public’s attention. Even though her unorthodox style was often misunderstood, Kennedy insisted that “we understand feminism [and sexism] better because of the discrimination against Black people.”5

A Tale of Two Protests: The Miss America Pageant Protests of 1968

On September 7, 1968, the veiled dichotomy between race and gender came alive through two distinct protests that contested the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey—one cried for death to the pageant, and the other called for rebirth. While the second-wave feminist movement criticized the pageant for its sexism and promotion of oppressive beauty standards, the black nationalist protest created a black rival pageant called Miss Black America that challenged the lack of black female representation within the pageant franchise itself. Given the tension between both movements, lack of recognition in the media, and the discrimination faced on the mainstream women’s rights front, Kennedy’s contributions to the white liberationists’ Miss America protest become perplexing. Why did Flo Kennedy choose to be involved in the predominately white feminist protest when there was a Miss America protest led by black people? We can understand why Flo Kennedy did not involve herself in the black pageant by exploring the Black pageant’s preservation of beauty standards and white American traditions that sharply contrasted Kennedy’s radical and liberal style. As a result, she envisioned the Women’s Liberation as a gateway and platform for questioning other forms of oppression, such as the intersectionality black women faced. Kennedy was not choosing womanhood over her blackness, but rather choosing “primarily white feminist spaces”6 that had the potential to fundamentally challenge racism and sexism alike without having to perpetuate one hegemonic structure as a means of toppling the other.

Examining further the distinctions between the predominantly white feminist protest and the black nationalist protest is crucial in understanding the disparity in objectives that affected Kennedy’s participation in the protests. These differences elucidate the point that the exclusivity and lack of representation in the Miss America pageant were universal grievances shared by both movements, but their approaches in rectifying this problem diverged. Feminist groups fought the image of Miss America itself, while the alternative Black pageant fought the exclusion from that image. Its “visibility as a recurring referendum on American womanhood”7 attracted activists from both protests.

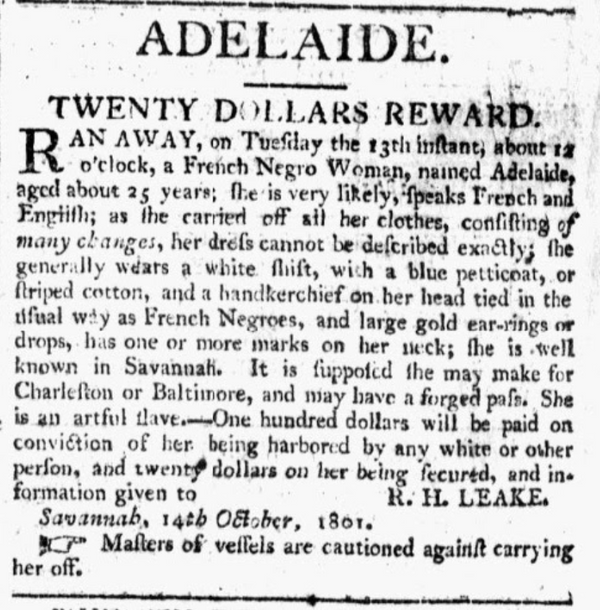

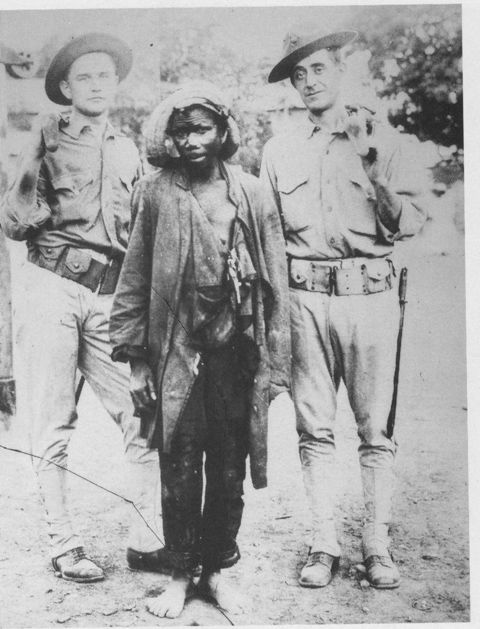

The friction between these two protests can be explained by historical underpinnings between the women’s liberation and black nationalism movements. Firstly, the Black Power movement’s tendency to trivialize the plight of black women reflected the sexist oppression that black women faced from not only outside the black community but also within.8 The black community instead glorified the ideal black woman to be one who supported the radical black man and resiliently subjected herself to the cause as a selfless auxiliary character.9 There was an inherent resentment towards feminism from the Black Power movement, as it was downplayed as distracting in the fight against racism. The equivocation of historical slavery to sexism through feminist propaganda, which had been designed to incentivize participation in the Miss America Boardwalk protest, further agitated that tension. To black people, rhetoric such as “slavery exists” and “keep women off the block”10 underscored the privilege of white women to ignore the prior systematic slavery of African Americans, and dispelled the sentiment that the oppression that white women faced was comparable to slavery11, which the civil rights movement believed diminished the value of their cause.

Despite how problematic this analogy was, Kennedy partook in public demonstrations that exacerbated the parallels between women and slavery. To emphasize how women were enslaved to beauty standards, Kennedy chained herself to a giant caricatured puppet of Miss America. Meanwhile, another demonstrator conducted the scene like a slave auction, announcing, “Yessiree boys, step right up! How much am I offered for this number one piece of prime American property?” Kennedy’s presence as a black woman within the Women’s Liberation enabled them to make these bodacious parallels through posters, live displays, and even parodied slave songs like “Down by the Riverside.”12,13 One might claim that the way that the feminist movement capitalized on Kennedy’s race for its own agenda created an unusual platform that made white feminism alienating to black women. Even so, Kennedy addressed the analogizing of black people and women, deeming it “too perfect to ignore.”14 The sole distinction that Kennedy made between women and the black community in activism was that women “didn’t see themselves as oppressed,” whereas black people would respond with a “shuffle and a ‘S’cuse me, boss’”.15 Here, we see emerging the distaste Kennedy had for the submissive and roundabout way that the black community fought oppression.

From Kennedy’s viewpoint, in this instance, the passive approach that the black community took was staging a “positive protest”17 by creating the Miss Black America pageant, which conformed to the same white beauty standards and respectability politics that diminished the black identity and undermined the potential to change the white institutions that governed black people’s lives. Its conception mirrored “the turn-the-other-cheek bullshit”18 that Kennedy criticized. In contrast with Kennedy’s perspective, the organizers of the Miss Black America called it an “affirmation of pride in Black Beauty and womanhood”19 and made it clear that “we’re not protesting against beauty.”20 The only distinction between both pageants was race—the pageant would be held in the same location—Atlantic City, New Jersey— with the same general guidelines. The black organizers emphasized that “we want to be in Atlantic City at the same time the hypocritical Miss America contest is being held. Theirs will be lily white and ours will be black.” It neither changed the fact that judges scavenged for “crooked teeth, heavy thighs, and crossed eyes,”21 nor the fact that feminine beauty was showcased for public consumption. Thus, the organizers of the pageant asserted the need for the beauty of the black woman to be “paraded and applauded as a symbol of universal pride,”22 which they hoped would empower black women to achieve a femininity that was traditionally inaccessible to them.23

Respectability Politics and Beauty Standards in Black Womanhood

In the black community, hair was the epitome of beauty—a crowning indication of class, especially for women. Upon further examination of black hair, it is evident that Miss Black America played a role in a set of politics that reinforced white beauty standards. While there was an insurgence of Black pride in the 1960s that was reinforced by the emergence of the Afro and natural styles, black beauty products that emulated white beauty standards were still popular outside of the realm of political activism. Substantial numbers of black women were switching to natural hairstyles, yet black people were still spending 30 percent of their salaries to satiate “their desire to look good, feel good, and smell good.”24 In fact, African Americans contributed to one-fifth of American beauty industry, meaning that they collectively spent $2.3 billion on their appearance. Appearance in the black community evoked messages about personal identity and even political affiliation. The majority of black Americans experienced the Civil Rights and Black Power movements through media and televised images, which idolized stylistic gestures and postures as reflective of political movements. Therefore, for black women, Afro and natural styles became synonymous with black militancy and “real defiance.”25 By virtue of the militancy and politicization of the Afro, young people who were committed to the civil rights movement sought this style. Contrarily, “the fraternities and sororities of the black elite” contested the Afro as a threat to the respectability they received from being apolitical and conforming to white standards. These visions of femininity and beauty were not created for black women, yet they strived in their behavior and appearance to emulate a countenance that warranted respectability.

Even with the media’s popularization and welcoming of natural black styles, upon closer inspection, we can see that the stigma projected from these styles was undesired by many black women, especially those who understood that apoliticism was a requisite for earning respectability. This reluctance to embrace the radical wave of natural hair from black women who wanted access to these spaces suggests a strong connection for black women between beauty and respectability politics. Apart from sisterhood and empowerment, women who wore unstraightened hairstyles still encountered derision in their workplaces, schools, and even homes. An overwhelming majority of women wore their hair straightened because women with long and wavy hair were prized for their “femininity.”26

Described as “curvy” and “hazel-eyed” with a hairstyle that was natural but not an Afro, Miss Black America Saundra Williams was presented in the media as “what the new black woman is all about.”28 This emphasis on Williams’s lighter eyes highlighted how the pageant celebrated black beauty with respect to how much it conformed to whiteness. Miss Black America expressed that: “‘With my title, I can show black women that they too are beautiful even though they do have large noses and thick lips.’” In spite of her intentions, the way Williams framed her statement suggested that the physical aspects of black women that veered from society's white definition of beauty needed to be overlooked and redeemed by qualities black women possessed that were proximate to white contours of beauty.

Similar to the way white beauty standards infiltrated black communities, respectability politics encouraged black women to mimic white-approved behavior in order to overcome racist stereotypes. Looking more carefully at Miss Black America speaking in her interview about the Women’s Liberation protest on September 9, 1968 in The New York Times, it is evident that she embodied this apolitical persona of the black elite. When asked a political question, she responded: “I hate to talk about this. It’s so controversial.” 29 Later in the interview, she appeared “bored when asked about the 100 women demonstrators, mostly white, who had picketed the Miss America Pageant,” commenting that “‘they’re expressing freedom, I guess . . . To each his own.’” 30 This reaction to the Women’s Liberation movement bears similarities to an opinion piece published on the same day in the New York Post by Harriet Van Horne, a white woman who denounced the “tasteless, idiotic behavior” of the Miss America feminists.31 Van Horne justified the behavior of protestors by asserting that they had never been made to feel “utterly feminine, desirable, and almost too delicate for this hard world.” However, black women had also never historically been made to feel this way. In fact, the stereotypes against black women solicited the exact opposite sentiments. So why did black women still feel like buying into these standards of beauty? It was an attempt to achieve a femininity that was inaccessible to them, particularly in an American society where femininity was the primary pathway to respect, inclusion, and second-class citizenship for women.

Black women’s pursuit of the unattainable standards of beauty attributed to white women explains Miss Black America’s skepticism when asked about the Women’s Liberation of pageants. These visions of femininity and beauty were not created for black women, yet they strived in their behavior and appearance to emulate a countenance that warranted respectability. Quite frankly, black women could not operate in both spaces. They could not both abide by respectability politics that would afford them femininity while also fighting against the very standards that precluded them from that realm of femininity made exclusive to white women. The Miss Black America pageant inadvertently encouraged black women to prove themselves respectable by conforming to the behavior outlined by white women, even though those standards diminished their own identity and undermined their ability to change those stereotypes. Conformity was “the key to the crown” and means to power, but this power was superficial because it relied on the approval of men and was restricted to a feminine context.32 Through drawing parallels between comments regarding the Miss America protest from Van Horne and Williams, we can identify a sense of skepticism and seemingly innocent but invalidating speculation of the motives behind the protesters’ objectives.33 Miss Black America’s disinterest with the Women’s Liberation protest distanced her from the radicalism that was looked down upon when in the process of earning respectability and femininity.

The Fluidity and Flexibility of Florynce Kennedy’s Activism

Regardless of the inclusion of black women into a standard not previously made for them, the Miss Black America pageant was endorsing a white beauty culture that “epitomized the roles we are all forced to play as women.”34 In the eyes of Kennedy, the Miss Black America pageant was a racially bounded microcosm of the white beauty standards that upheld the institution of Miss America. Indeed, it accounted for racial exclusion, but the transgressions of feminine respectability were not only maintained but reinforced through the genesis of Miss Black America. It validated the institution itself and even cultivated the need for one that extended this pretty privilege to black people. Even with the redefinition of a white tradition, inherent demands to conform manifested itself in a black form. Meanwhile, the Women’s Liberation movement “deplored Miss Black America as much as Miss White America but we [they] understand the black issue involved.”35

This intentionality in denouncing beauty contests while also recognizing the gaps in racial representation aligned with Kennedy’s vision of fighting the common enemy she labeled as “the racist sexist genocidal establishment.” It recognized that white supremacy works in tandem with patriarchy to marginalize black women, who, though technically belonging in conversations of racial uplift and feminism, fail to be included in the benefits of either pursuit. Aware of the reality that “black women have felt between the loyalties that bind them to race on one hand, and sex on the other… yet they have almost always chosen race over the other: a sacrifice of their self-hood as women and of full humanity, in favour of the race,” Kennedy rejected the popular falsehood that women’s subjugation was a requisite of black liberation—deactivating her access to feminism by upholding sexist standards in the name of racial representation was counterproductive.36 The complete rights of each individual aspect of her humanity were not up for negotiation.

Over the course of her career, Kennedy refused to conform to standards of beauty and respectability within the black community and beyond. In fact, Kennedy addressed in an interview the painful trauma that young black people underwent in seeing “their parents do everything in the world to be a part of the white community and being rejected.”37 Even Kennedy herself had experienced this rejection when, “As nicely and conservatively as I was dressed, I was still just another nigger.”38 After these confrontations, Kennedy refused to allow “the civil rights ethos of using respectability to earn citizenship”39 govern the way she operated on the political stage. Rather, Kennedy rebelled against politically correct dress codes and feminine standards by intentionally wearing flamboyant clothing, cursing, and branding her public image as distinct and radical. The civil rights tradition of picketing commonly induced women to dress in their Sunday best, like a respectable lady.40 But in participating in the Women’s Liberation Movement, Kennedy was accepted in whatever wardrobe she fancied.

When detailing her experience protesting the “lily-white, racist contest” in Atlantic City, Kennedy attested that it was “the best fun I can imagine anyone wanting to have on any single day of her life” because “it was very brazen and very brash, and there were some arrests.”42 Kennedy certainly did her part in radicalizing the protest to be her version of fun. This is exemplified in her work in instructing young feminists on Black Power tactics, therefore “shaping contemporary feminist struggles.” She managed to leave a significant cultural stamp on South Jersey, which was further imbued when she opened protest headquarters in the Atlantic City black community as a safe haven for white feminists to eat a soul food supper, change clothes, and rest.43 Logistically, Kennedy spearheaded the transportation of women to Atlantic City headquarters and secured New Jersey permits for protest. As the resident attorney, Kennedy was also legally responsible for lowering the bail of those arrested. In addition, she was the co-organizer or “advisory sponsor” of the demonstration through her Media Workshop.44

In contrast to the black nationalist version of protest, as can be seen by the variety of roles she juggled, Kennedy could exercise her mobility to transform the Women’s Liberation movement. It was a window of opportunity for her to challenge both the feminist and racial matters that the movement was prioritizing through the eyes of all women—not just white women. Even though Kennedy avidly participated in the Atlantic City Miss America protests, “she felt most comfortable being the leader of her own battles.” 45 In fact, Kennedy did not attach herself to movements. She cut across them. Kennedy fluidly traversed across movements depending on how she could best accomplish her mission of building coalitions that fought hegemonic oppression in unison. Rather than serving as the hallmark of a singular protest, she much rather preferred being the cornerstone between intersectional causes.

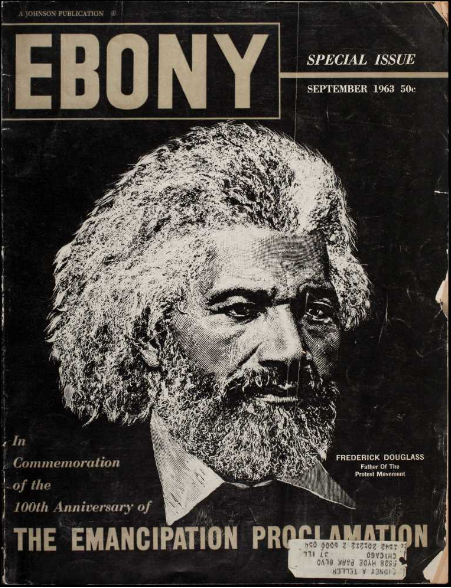

Despite her transformative work in preparing the Women’s Liberation Movement for “its first major militant demonstration,”46 Kennedy was erased by the media—her work downgraded to being one of “lots of women lawyers.” Because Kennedy served as the bridge between the civil rights movement and women’s liberation movement of her time, it may appear that the racial component of the protest that justified Kennedy’s place in the Miss America protest was eradicated once the media removed Kennedy from the picture. Indeed, Kennedy was the voice for black women; however, the novel methods she introduced to white feminists were distinguishable to the media as being adopted from radical black nationalist strategies. Therefore, albeit the public actively worked to erase her image, her impact not only influenced the movement but built it to be as effective as it was. Kennedy’s awareness of being overlooked by the media, who she called “such clumsy liars” with “tit focus,”47 emboldened her flamboyant style in protesting and retaliating against the repressive forces that tried to silence her and pacify her intentions. Being involved in the Miss Black America pageant would have also arguably made Kennedy more invisible, primarily because the organization was male-dominated. But secondly, the novel radical activism methods that illuminated her in the Women’s Liberation movement, such as boycotts of advertisers and guerilla theatre protests, would not have rendered her as influential in the civil rights movement.

Through Kennedy’s devotion to intersectionality and refutation of beauty standards and respectability politics, we can see that Kennedy was unafraid of braving an unconventional atmosphere for a black woman and revolutionizing it to do more for people like herself. Kennedy marched on the Atlantic City Boardwalk because the issue was larger than the fact that black women were not included in the perception of the ideal American woman; the problem was that there was an ideal American woman. Even though the Miss Black America pageant outwardly addressed the plight of black women specifically, the intersectionality of black women was not fully accounted for through the pageant’s methods because the solution still relied on beauty standards and white male hegemony.

By virtue of this reliance, the black nationalist protest was just not radical enough. This perpetuation of beauty standards and maintenance of respectability politics was simply not Kennedy’s style as a woman who was known to “challenge the establishment” with “street theatre and shock tactic.”49 Therefore, Flo Kennedy, departed from that movement and worked towards ameliorating the standards in which women were viewed, acting as a voice for black women in a movement where they were an anomaly. The Women’s Liberation Group aligned with Kennedy’s ideals by recruiting “Movement women” who were tired of “playing home-fires to their revolutionaries” or being called frivolous “when more serious revolutionary problems are at stake.”50 This space provided solidarity for sexism, acted as a union of women under a common oppression, and had potential for Kennedy to leverage advocacy for black people, as well. Kennedy emphasized how “the Women’s Liberation Movement can function as the cutting edge of a larger movement...to mobilize an oppressed majority”51 because “empathy for other oppressed groups is magnified when it’s your own thing.”52

Conclusion

Ultimately, Kennedy partook in the Women’s Liberation movement protest because it provided her greater opportunity to radically reject normative beauty standards, respectability, and racism. Albeit the public actively worked to erase her image, her impact not only influenced the movement but built it to be as effective as it was. As a byproduct of her influence, protestors unaccustomed to black culture in South Jersey were forced to be immersed in the formerly invisible and silenced presence of the black community in Atlantic City. Despite the existing tension and competitiveness between the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements, Kennedy served as a liaison for alliances between both movements. She believed that they both fundamentally struggled in an oppression that “hurt like crazy.”53 Perhaps this engagement of movements through intersectional organizing can be applied to the way racial biases are reflected within the #MeToo Movement and the way black women operate as the bedrock of the Black Lives Matter protest while seldom receiving credit or recognition for their efforts. Kennedy’s reasons behind choosing to operate within one movement may seem personally derived, but they can serve as a lens in understanding how race and gender movements manifest themselves in today’s public consciousness.

Bibliography

Bronner. “Why Blacks spend billions to look good” Jackson Advocate, December 11-17, 1968.

Charlotte Curtis special to The New York Times. "Miss America Pageant Is Picketed by 100 Women." New York Times (1923-Current File) (New York, N.Y.), 1968.

Cohen, Bonny. American Beauty, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Craig, Maxine. Ain't I a Beauty Queen?: Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Oxford Scholarship Online, 2011. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152623.001.0001.

Curtis, Charlotte, "Along With Miss America," The New York Times, September 9, 1968, pg. 54.

Demonstration information for Miss America protest, Sept. 7, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Demonstration information for Miss America protest, Sept. 7, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Dow, Bonnie J. "The Movement Meets the Press: The 1968 Miss America Pageant Protest." In Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Chapter 002. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Female Firebrands, by Harriet Van Horne, Sept. 9, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Flo Kennedy Miss America Goes Down, by Robin Morgan, Oct. 3, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Gallagher, Julie. "Sherie M. Randolph . Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical." The American Historical Review 122, no. 1 (2017): 209-10.

Georgia Paige Welch. "“Up Against the Wall Miss America”: Women’s Liberation and Miss Black America in Atlantic City, 1968." Feminist Formations 27, no. 2 (2015): 70-97. https://muse.jhu.edu/

Giddens, Suzanne. Atlantic City is a town with class, they raid your morals and judge your ass, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Gore, Dayo F., Jeanne. Theoharis, and Komozi. Woodard. Want to Start a Revolution? : Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Grant, Jacquelyn. "A Black Response to Feminist Theology ." In Women's Spirit Bonding, eds. Janet Kalven and Mary Buckley. New York: The Pilgrim Press, 1984.

Griggs, Brandon. “The Most Turbulent Time in Modern American History (It's Not Now).” CNN. Cable News Network, May 18, 2018.

Handwritten and typed drafts of protest songs for the 1968 Miss America protest, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Hill Collins, Patricia. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. 2nd edition. London ; New York, New York: Routledge, 2014.

“It Happened Here in New Jersey: Miss America.” It Happened Here in New Jersey: Miss America. Kean University and the New Jersey Historical Commission, 2015.

Kennedy, Florynce. Color Me Flo : My Hard Life and Good times. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

Klemesrud, Judy, "There's Now Miss Black America," The New York Times, September 9, 1968, pg. 54.

Lane, Bettye , 1930-2012, “Matriarchy conference with Ti-Grace Atkinson, Flo Kennedy, Gloria Steinem, and Kate Millett,” Catching the Wave, Schlesinger Library.

Letter from Robin Morgan to Richard S. Jackson, Mayor of Atlantic City, Aug. 29, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Morgan, Robin. Sisterhood Is Powerful : An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement. Vintage Book ; V-539. New York: Vintage Books, 1970.

Newsreel (Firm). 2000. Up against the wall, Ms. America. New York, NY: Third World Newsreel.

No More Miss America!, Florynce Kennedy Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

No More Peace Teas, by Suzanne Giddens, Sept. 26, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

On Freedom for Women, by Robin Morgan, from Liberation, October 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Randolph, Sherie M., Robin D. G. Kelley, Beverly Guy-Sheftall, Adam Green, Lisa Duggan, Martha Hodes, and Barbara Krauthamer. 2007. "Alliance of the alienated": Florynce "Flo" Kennedy and black feminist politics in post World War II America. Dissertation Abstracts International. 69-01.

Sherie M. Randolph. Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015. https://muse.jhu.edu/

Simien, Evelyn M., and Danielle L. McGuire. “A Tribute to the Women: Rewriting History, Retelling Herstory in Civil Rights.” Politics & Gender 10, no. 3 (2014): 413–31. doi:10.1017/S1743923X14000245.

Simons, Margaret A. "Racism and Feminism: A Schism in the Sisterhood." Feminist Studies 5, no. 2 (1979): 384-401. doi:10.2307/3177603.

Slavery Exists: Miss America is a Slave, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Endnotes

1. “It Happened Here in New Jersey: Miss America.” It Happened Here in New Jersey: Miss America. Kean University and the New Jersey Historical Commission, 2015.

2. Georgia Paige Welch. "“Up Against the Wall Miss America”: Women’s Liberation and Miss Black America in Atlantic City, 1968." Feminist Formations 27, no. 2 (2015): 68.

3. Georgia Paige Welch. “Up Against the Wall Miss America”: 71.

4. Dow, Bonnie J. "The Movement Meets the Press: The 1968 Miss America Pageant Protest." In Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Chapter 002. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

5. Gore, Dayo F., Jeanne. Theoharis, and Komozi. Woodard. Want to Start a Revolution? : Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

6. Gallagher, Julie. "Sherie M. Randolph. Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical." The American Historical Review 122, no. 1 (2017): 209-10.

7. Dow, Bonnie J. "The Movement Meets the Press: The 1968 Miss America Pageant Protest." In Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Chapter 002. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

8. Simien, Evelyn M., and Danielle L. McGuire. “A Tribute to the Women: Rewriting History, Retelling Herstory in Civil Rights.” Politics & Gender 10, no. 3 (2014): 413–31. doi:10.1017/S1743923X14000245.

9. Simien, Evelyn M., and Danielle L. McGuire. “A Tribute to the Women: Rewriting History, Retelling Herstory in Civil Rights.”.

10. Slavery Exists: Miss America is a Slave, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

11. Simons, Margaret A. "Racism and Feminism: A Schism in the Sisterhood." Feminist Studies 5, no. 2 (1979): 384-401. doi:10.2307/3177603.

12. Handwritten and typed drafts of protest songs for the 1968 Miss America protest, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

13. Georgia Paige Welch. "“Up Against the Wall Miss America” 78.

14. Morgan, Robin. Sisterhood Is Powerful : An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement. Vintage Book ; V-539. New York: Vintage Books, 1970.

15. Morgan, Robin. Sisterhood Is Powerful,1970.

16. Kennedy, Florynce. Color Me Flo : My Hard Life and Good times.

17. Georgia Paige Welch. "“Up Against the Wall Miss America”

18. Morgan, Robin. Sisterhood Is Powerful, 1970.

19. Georgia Paige Welch. “Up Against the Wall Miss America”: 74.

20. Curtis, Charlotte, "Along With Miss America," The New York Times, September 9, 1968, pg. 54.

21. Cohen, Bonny. American Beauty, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

22. Charlotte Curtis special to The New York Times. "Miss America Pageant Is Picketed by 100 Women." New York Times (1923-Current File) (New York, N.Y.), 1968.

23. Cohen, Bonny. American Beauty, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

24. Bronner. “Why Blacks spend billions to look good” Jackson Advocate, December 11-17, 1968.

25. Craig, Maxine. Ain't I a Beauty Queen?: Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Oxford Scholarship Online, 2011. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152623.001.0001.

26. Craig, Maxine. Ain't I a Beauty Queen?: Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race.

27. Dow, Bonnie J. "The Movement Meets the Press: The 1968 Miss America Pageant Protest," 40.

28. Curtis, Charlotte, "Along With Miss America," The New York Times, September 9, 1968, pg. 54.

29. Klemesrud, Judy, "There's Now Miss Black America," The New York Times, September 9, 1968, pg. 54.

30. Klemesrud, Judy, "There's Now Miss Black America,"

31. Female Firebrands, by Harriet Van Horne, Sept. 9, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

32. Dow, Bonnie J. "The Movement Meets the Press: The 1968 Miss America Pageant Protest." In Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Watching Women's Liberation, 1970, Chapter 002. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

33. Female Firebrands, by Harriet Van Horne, Sept. 9, 1968.

34. No More Miss America!, Florynce Kennedy Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

35. Charlotte Curtis special to The New York Times. "Miss America Pageant Is Picketed by 100 Women."

36. Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd edition. (London ; New York, New York: Routledge, 2014), 132.

37. Kennedy, Florynce. Color Me Flo : My Hard Life and Good times. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

38. Georgia Paige Welch. “Up Against the Wall Miss America”: 82.

39. Georgia Paige Welch. “Up Against the Wall Miss America”: 82.

40. Georgia Paige Welch. “Up Against the Wall Miss America”: 91.

41. Lane, Bettye , 1930-2012, “Matriarchy conference with Ti-Grace Atkinson, Flo Kennedy, Gloria Steinem, and Kate Millett,” Catching the Wave, Schlesinger Library.

42. Kennedy, Florynce. Color Me Flo : My Hard Life and Good times. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

43. Demonstration information for Miss America protest, Sept. 7, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

44. Handwritten and typed drafts of protest songs for the 1968 Miss America protest, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

45. Randolph, Sherie M., Robin D. G. Kelley, Beverly Guy-Sheftall, Adam Green, Lisa Duggan, Martha Hodes, and Barbara Krauthamer. 2007. "Alliance of the alienated": Florynce "Flo" Kennedy and black feminist politics in post World War II America. Dissertation Abstracts International. 69-01.

46. On Freedom for Women, by Robin Morgan, from Liberation, October 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

47. Kennedy, Florynce. Color Me Flo : My Hard Life and Good times. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

48. Griggs, Brandon. “The Most Turbulent Time in Modern American History (It's Not Now).” CNN. Cable News Network, May 18, 2018.

49. Randolph, Sherie M. "Alliance of the alienated": Florynce "Flo" Kennedy and black feminist politics in post World War II America. Dissertation Abstracts International. 69-01.

50. Miss America Goes Down, by Robin Morgan, Oct. 3, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

51. On Freedom for Women, by Robin Morgan, from Liberation, October 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

52. No More Peace Teas, by Suzanne Giddens, Sept. 26, 1968, Robin Morgan papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University53. Kennedy, Florynce. Color Me Flo : My Hard Life and Good times. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1976.