Volume 25: April 5, 2021

Reading Shakespeare’s Plays in the Old West

By London Johns

In 1879, Colonel William G. Boyle, the owner of most of the land in a small mining town in New Mexico named Ralston City, was determined to heal the town’s reputation. Since 1870, Ralston City had attracted thousands of people hoping to mine for silver in the surrounding hills. But when a rumor of diamonds in the hills was revealed to be a lie, Ralston City’s population quickly declined. Hoping to erase the town’s association with the hoax, Boyle renamed the town Shakespeare and founded the Shakespeare Gold and Silver Mining and Milling Company to draw in new residents, a plan that would succeed until the depression of 1893 (“Shakespeare”). Boyle’s naming choice -- and its success -- demonstrated a cultural adoration and familiarity with Shakespeare’s works in the Old West. Practically everyone read Shakespeare, and those that were not literate asked others for help; Jim Bridger, a “mountain man” and fur trader, memorized sections of Shakespeare and paid a boy to read the plays to him (Dickson). In areas of the American frontier where theaters were few and far between, why were Shakespeare’s plays still so popular? They benefited from a combination of the isolated lifestyle of people living on the frontier and an increasing number of adaptations of the plays that conformed to Romantic principles.

Cowboys often lived solitary, lonely lives, a fact that was represented in their songs. Many cowboy songs mentioned partners abandoned in favor of a life of isolation, and in songs that bragged of some great achievement or ability, the idea of a solemn, reclusive life was prominent: “When I'm hot there's an equinoxical breeze that fans me fevered brow,/The moans of widows and orphans is music to me melancholy soul” (qtd. in Cadlo 399). “The Dying Cowboy” or “The Lone Prairie”, a cowboy song from the 1880s, was centered on the speaker’s miserable isolation: “Oh, bury me not on the lone prairie. ‘Oh, bury me not,’ and his voice failed there;/But they listened not to his dying prayer” (Hull). Even in death, the cowboy was not able to escape his solitude. His body was forced to remain where he travelled alone. Seeking comfort, companionship, and entertainment, some cowboys turned to classic literature, and many to Shakespeare’s works in particular. One cowboy discovered a copy of Shakespeare’s works in a covered wagon meant to transport food and never put it down: "During the rest of my enforced hermit life I consoled myself with it” (qtd. in Van Orman 36). At a ranch where there were accessible copies of books including Shakespeare’s works, though other visitors chose to read contemporary novels, “cowboys alone attacked the Shakespeare” (Rollins 171). Something about Shakespeare’s works called to cowboys over other classics, and even over novels of the time.

There were several reasons for the popularity of Shakespeare’s works. Copies of Shakespeare’s works were widespread. They could be found alongside the Bible in nearly every home. Because they were not copyrighted, they were also inexpensive -- so inexpensive that one tobacco company gave them away for free. Along with each case of tobacco came a coupon for a paperback copy of a classic off of a list of three hundred and three books. Eugene Manlove Rhodes named the distribution of these coupons as the catalyst for rising literacy among cowboys:

“Cowboys all smoked: and the most deep-seated instinct of the human race is to get something for nothing. They got those books. In due course of time they read those books. Some were slow to take to it; but when you stay at lonely ranches, when you are left afoot until the water-holes dry up, so you may catch a horse in the waterpen--why, you must do something. The books were read. Then, having acquired the habit, they bought more books.” (Rhodes 66)

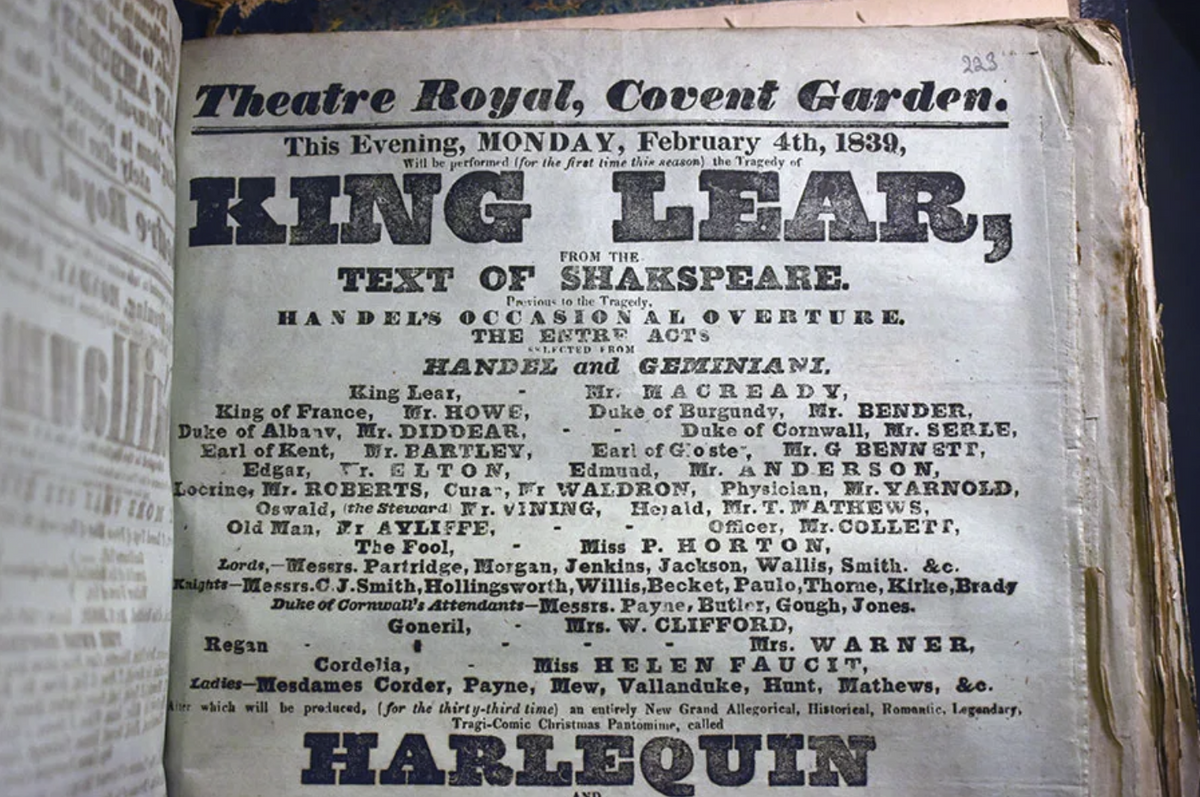

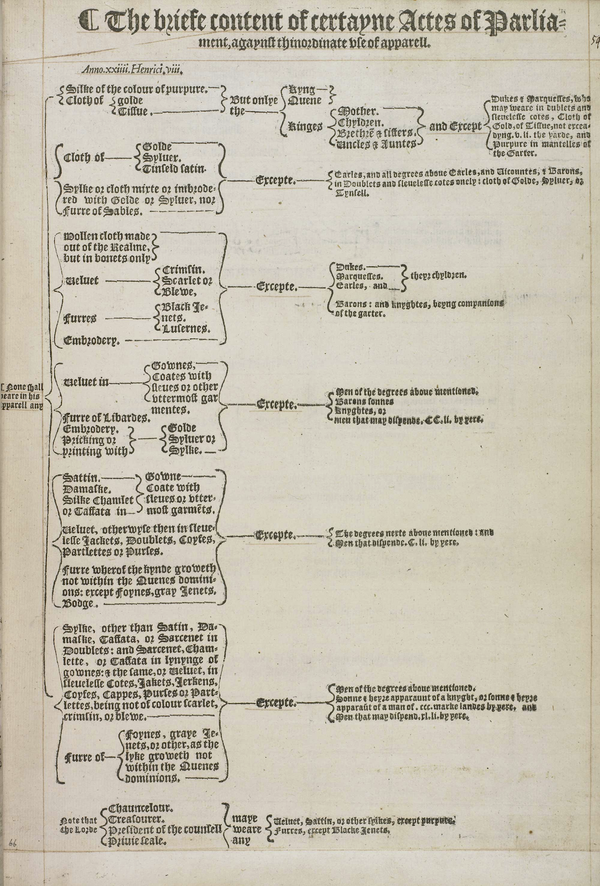

Though they were used as a comfort, the most popular of Shakespeare’s plays were not comedies. Richard III was the most popular play in the 19th century (Levine 14), and when cowboys chose Shakespeare’s works from the books at the ranch, they tended to opt for tragedies or histories. Tragedies and history plays had cathartic appeal. They were grittier than melodramatic novels or comedies, and to people who dealt constantly with the dangers of the wild and the emotional effects of prolonged isolation, intense, bloody tragedies likely seemed more relevant. One cowboy, reading Julius Caesar, remarked, “Gosh! That fellow Shakespeare could sure spill the real stuff. He’s the only poet I ever seen what was fed on raw meat” (Rollins 171).The other factor that could have contributed to the popularity of Shakespeare’s tragedies over his comedies was the fact that they were not always performed in their original forms. Adaptations of Shakespeare’s tragedies replaced their tragic conclusions with more optimistic endings. Many authors of the time believed that there were flaws in Shakespeare’s works that they could improve with changes to the writing and plot. Between 1660 and 1820, all of Shakespeare’s plays had been adapted, and by 1820 there had been 123 total adaptations of his works (Wheeler 438). Perhaps the most successful of these was Nahum Tate’s version of King Lear, which ended not with the deaths of Lear and Cordelia, but with Cordelia marrying Edgar and Lear becoming king once again. This version of the play was performed instead of Shakespeare’s original text on English stages beginning in 1681. American productions inherited it, and the original King Lear did not return to the stage until 1838, when actor William Charles Macready chose to restore the play to a (significantly shortened) version of Shakespeare’s own text (“Stage History: King Lear”).

Tate did not want to leave the stage “incumbered…with dead Bodies” (qtd. in Spencer), and his changes eliminated most of the tragic elements of King Lear’s plot. He removed Edgar’s hopeless final line, “the oldest hath borne most; we that are young/Shall never see so much nor live so long” (Shakespeare, King Lear 5.3.392-395). In its place, Edgar declares that his country has achieved peace at last, and that Cordelia’s “bright Example shall convince the World/(Whatever Storms of Fortune are decreed)/That Truth and Vertue shall at last succeed” (Tate 60). Instead of ending on a pessimistic note, Tate’s King Lear ends like Richard III, with the assurance that troubled times are over and the kingdom is entering a new era of peace. Edgar’s final lines themselves are similar to Richmond’s:

“Let them not live to taste this land’s increase,

That would with treason wound this fair land’s peace.

Now civil wounds are stopped, peace lives again.

That she may long live here, God say amen.” (Shakespeare, Richard III 5.5.38-41)

Tate’s edits, including his addition of a clear motive for Cordelia’s disobedience and the exclusion of the Fool from the play, made King Lear less complicated and more palatable to audiences who were not interested in being heartbroken by the play’s ending. Though it has since been abandoned, audiences preferred Tate’s interpretation for over 150 years.

The cultural importance of Shakespeare’s works has often relied upon performance. Most of Shakespeare’s own audience was illiterate, and many of his plays were not published in print until after Shakespeare’s death. However, in places in the Old West where permanent theaters had not yet been established and not all residents were literate enough to read his plays with ease, Shakespeare’s works were already beginning to intertwine with American institutions, and the preferences of American audiences were changing how Shakespeare’s plays were interpreted.

Works Cited

Cadlo, Joseph J. “Cowboy Life as Reflected in Cowboy Songs.” Western Folklore, vol. 6, no. 4, 1947, pp. 335–340. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1497666. Accessed 2 Apr. 2021.

Dickson, Andrew. “West Side Story: How Shakespeare Stormed America's Frontier.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Apr. 2016, www.theguardian.com/stage/2016/apr/15/william-shakespeare-american-west-pioneers.

“Edwin Booth as Richard III.” Shakespeare's Staging, Hugh Macrae Richmond, 2016, shakespeare.berkeley.edu/images/richard-iii-edwin-booth-as-richard-iii.

Hull, Myra. “Cowboy Ballads.” The Kansas Historical Quarterly, VIII, no. 1, Feb. 1939, www.kshs.org/p/cowboy-ballads/12777.

LaGrand, Alexandra E. “William Charles Macready and the Restoration of William Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear’ .” Shakespeare & Beyond, Folger Shakespeare Library, 18 Aug. 2020, shakespeareandbeyond.folger.edu/2020/08/18/william-charles-macready-king-lear-restoration/.

Levine, Lawrence W. Highbrow/Lowbrow. Harvard University Press, 1988, Internet Archive, archive.org/details/highbrowlowbrowe00levi_0/.

Rhodes, Eugene Manlove. Bransford of Rainbow Range. The H. K. Fly Company, 1920, Project Gutenberg, www.gutenberg.org/files/33498/33498-h/33498-h.htm.

Rollins, Philip Ashton. The Cowboy; His Characteristics, His Equipment . C. Scribner's Sons, 1922, Internet Archive, archive.org/details/cowboyhischarac00rollgoog/.

“Shakespeare.” New Mexico True, New Mexico Tourism Department, 2021, www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/ghost-towns/shakespeare/.

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 113.

Shakespeare, William. Richard III. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 113.

Spencer, Christopher. “A Word for Tate's King Lear.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 3, no. 2, 1963, pp. 241–251. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/449297. Accessed 2 Apr. 2021.

“Stage History: King Lear.” Royal Shakespeare Company, Royal Shakespeare Company, 2021, www.rsc.org.uk/king-lear/past-productions/stage-history.

Tate, Nahum. The History of King Lear: Acted at the Queens Theatre . Printed for Rich. VVellington, at the Dolphin and Crown in St. Paul's Church-Yard ; and E. Rumbold at the Post House, Covent-Garden; and Tho. Osborne at Grays-Inn, near the VValks, 1702, Internet Archive, archive.org/details/historyofkinglea00tate_6/.

Van Orman, Richard A. “The Bard in the West.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 1, 1974, pp. 29–38. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/967188. Accessed 2 Apr. 2021.Wheeler, David. “Eighteenth-Century Adaptations Of Shakespeare and the Example of John Dennis.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4, 1985, pp. 438–449. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2870307. Accessed 2 Apr. 2021.