Annales Yalensis is a weekly column aimed at highlighting the interesting, absurd, and impactful events of world history and their representations within the historical archives of Yale University.

Queen Elizabeth By Louie Lu

On November 17th, 1558, Elizabeth I Tudor ascended the English throne, succeeding her half-sister Mary I. She was the last of the Tudor line to rule England, and her reign is considered a golden age.

Born to Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn, she was the heir-presumptive until her mother’s execution just two years after her birth deprived her of her legitimate status, and her newborn half-brother would later become Edward VI. Edward’s early death allowed Mary to ascend the throne, whose Catholic zeal and persecution of heretics made the Protestant Elizabeth a rallying point for religious opposition. Despite a near encounter with execution for treason, Mary spared Elizabeth and soon passed away from illness.

The divide between English Catholics and Protestants as well as the lack of clear male succession encouraged plots to depose the sitting monarch, and religious persecutions and conflicts left England in a state of unrest and violence. Thus, one of Elizabeth’s first initiatives was her Elizabethan Religious Settlement, which set out to create a religion that both Catholics and Protestants could accept, a compromise between the two sides. This settlement would serve as one of the foundations of the Church of England, healing some of the religious rifts that had torn the country apart. She would be opposed by radical Puritans and Catholics insisting on strict adherence to doctrine for the rest of her reign.

This queen’s former illegitimate status rendered her vulnerable to conspiracies, and she had to establish spy networks and brutally put down rebellions to avoid deposition. One such instance involved her relative Mary, Queen of Scots. Elizabeth’s insecure position led her to constantly avoid confrontation with her government.

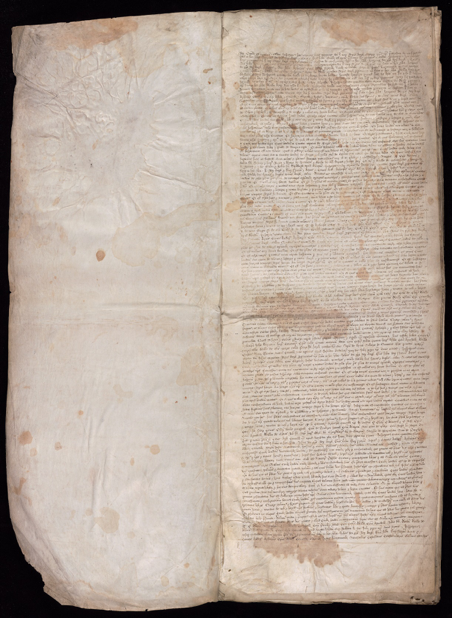

Elizabeth’s reign would also be known for rich artistic flourishing, especially in literature and theatre. Writers like Edmund Spenser and playwrights like Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare found great success and played important roles in developing the English language. The queen did not just sponsor entertainment but also participated in it. The document below is a unique artifact from the archives of the Elizabethan Club at Yale. It is a rare piece of dramatic composition of the queen’s own hand, being composed as a part of her participation in the Theobalds Entertainment of 1591, an extended hosting of the queen by her Lord High Treasurer, Lord Burghley, in his Hertfordshire house, Theobalds. In it, the queen responds to the petition of a Hermit requesting the right to retire from public service by drawing up a charter affixed with the Great Seal granting her “woorthely belooved Coounceloour” the right to retire back to his “cave” and “own houus.”

She also sponsored colonial activities abroad like the settlement of North America’s east coast, with explorers like Sir Walter Raleigh naming what is now the American state of Virginia after the queen. She also encouraged mercantile activity in other parts of the world, founding the East India Company.

Her naval commanders, notably Sir Francis Drake, often turned to piracy, looting Spanish galleons bringing back silver from the New World. King of Spain Phillip II’s claim to the English throne as the deceased Mary’s husband as well as his religious conviction to reconvert England to Catholicism induced him to launch a maritime invasion of the island with the Spanish Armada of 130 ships. This map from the Yale Center for British Art by Baptista Boazio records Drakes Great Expedition to America of 1585 to 1586, a preemptive strike against Spanish colonies in the Americas.

Elizabeth, donning a silver breastplate, declared, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any Prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm”. Owing to a combination of Spanish incompetence, the ingenuity of Elizabeth’s commanders, and simply bad weather, England succeeds in repelling the Spaniards, a moment that forged a sense of English national identity. However, materially England had to sustain heavy debts to fund the war against Spain, and the debt passed on to Elizabeth’s successor.

In the painting An Allegory of the Tudor Succession: The Family of Henry VIII, one can see Elizabeth to the right of her father, holding the hand of the allegorical representation of Concord behind whom is Prosperity holding a cornucopia. This association contrasts with Mary and her husband Phillip II of Spain who are flanked by Mars, the god of war. The painting reflects her role in bringing religious peace and guaranteeing England’s independence from foreign powers.

Throughout Elizabeth’s reign, she remained unmarried, emphasizing her virginity. She outwardly claimed that she was looking for a partner, and later as it was apparent that she would never marry, that she was married to all her subjects. She likely avoided marriage to prevent a husband from diminishing her own political power, as Phillip had with Mary. She also worried that having a certain heir, even her own child, might inspire plots to depose her. She also used her marriage to incentivize or threaten her advisors. Thus, she would be known as the Virgin Queen, described as having immortal beauty in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene.

Queen Elizabeth I would be also known as Gloriana or Good Queen Bess, and her pragmatism and occasional decisiveness navigated England through a turbulent era of its history. At her deathbed, she declared James Stuart of Scotland as her successor, bringing England and Scotland into a union that exists to this day.

Bibliography

Boazio, Baptista. “The Famouse West Indian Voyadge Made by the Englishe Fleete of 23 Shippes and Barkes [Cartographic Material] : Wherin Weare Gotten the Townes of St . Iago, Sto. Domingo, Cartagena and St. Augustines : The Same Beinge Begon from Plimmouth in the Moneth of September 1585 and Ended at Portesmouth in Iulie 1586 : The Whole Course of the Saide Viadge Beinge Plainlie Described by the Pricked Line.” London, 1589. Paul Mellon Collection. Yale Center for British Art. https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/orbis:9589717.

Elizabeth I, Queen of England. “Elizabetha Anglo[Rum], Id Est a Intore Angelo[Rum] Regina Fformosissima & Felicissima. Too the Disconsolate & Retyred Spryte, the Hermyte of Tybolles.,” May 10, 1591.

Wuhrer, L. “Les Principes Du Président Wilson et Les Aspirations Italiennes En Carinthie, Dans La Province de Goritz et En Carniole = The Principles of President Wilson and the Italian Aspirations in Carinthia, in the Provinces of Gorice and Carniola / Lith. L. Wuhr.” L. Wuhrer, 1919.

The Amityville Horror Murders By Taylor Barton

On November 13th, 1974, a horrific event occurred that would inspire several books and horror films in the years to come. On this day in history, Robert DeFoe Jr. killed his parents and four siblings in their home in Amityville, New York.

The DeFoe family, including parents, Robert, 43, and Louise, 42, two sons, John, 9, Mark, 12, and Robert Jr., 23, and two daughters, Allison, 13, and Dawn, 18, lived at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, New York in their colonial style home. On one fateful night in November, the eldest son, Robert Jr., murdered his entire family by shooting them in their beds with a .35 Marlin rifle.

After killing his family, he fled to a nearby bar where he told the customers that he had found the dead bodies of his family. Several men followed Robert back to the house and called the police to report the murders. When the police arrived, Robert claimed he had found the bodies at 6pm that day when he came home to a locked house. The police saw no signs of struggle nor did they find the murder weapon. Robert immediatly became the prime suspect, and within two days of the murders, he would be arrested for six second-degree murder charges. For his trial, DeFoe’s lawyers acquired a psychiatrist who claimed DeFoe had been in a state of paranoid psychosis when he murdered his family, in an attempt to claim insanity. However, psychiatrists hired by the prosecution argued that, although he was indeed mentally ill, he did not fit the legal definition of insane. This argument swayed the jury, and DeFoe was sentenced to six life sentences.

Only thirteen months after the murders, the home was bought by the Lutz family at a severely reduced price, before they ultimately left only 28 days later. Father, George Lutz, claimed the sudden move was “because of our concern for our own personal safety as a family.” In the 28 days they stayed in the house, they had experienced an onslaught of paranormal activity that made them fear for their lives and flee. The Lutz family’s predicament made headlines, causing many believed the paranormal activity was due to the mass murder of the DeFoe family that had occurred little over a year before.

The DeFoe murders, along with the claimed haunting of the Lutz family, would inspire a myriad of books and films in the coming years that would perpetuate the legend of the “Amityville Horror.” Once the book, The Amityville Horror by Jay Anson was published, the media's obsession with the event began. This book can be found in the Yale Online Library, along with many other books and films about this event. The film rights of the book were sold, and in 1979, the original Amityville Horror film would be released to the public. The film was a hit, just as the book had been. As the years went on, countless books and films were released about the event. Even in the past three years, several Amityville inspired films have been produced, proving that the public’s obsession with the event is far from over, despite it occurring 46 years ago.

Bibliography

Dean, Michelle. "The True Story of Amityville Horror." Topic, Oct. 2017, www.topic.com/the-true-twisted-story-of-amityville-horror. Accessed 1 Nov. 2020.

"The Real 'Amityville Horror.'" Biography, 14 Oct. 2020, www.biography.com/news/the-real-amityville-horror-facts. Accessed 1 Nov. 2020.

Schmetterer, Jerry. "6 in L.I. Family Found Shot to Death." Daily News [New York], 14 Nov. 1974. New York Daily News, www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/shocking-amityville-murders-40-years-article-1.2010236. Accessed 1 Nov. 2020.

Armistice Day By Louie Lu

At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, four years of bloody fighting with millions of casualties across Europe finally came to an end. Germany signed an armistice with the allied powers of Britain, France, and the United States, ending all hostilities with its enemies. The last arena of World War I, the Western Front, went silent — no longer would there be the incessant explosions of shells in the Belgian and French countryside.

In 1914, the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand dragged virtually all the Great Powers of Europe into a single war. Great Britain, France, Russia, and later the Italians would form the Entente fighting against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria Hungary, and Turkey. Over the span of four years, countless soldiers would charge to their deaths, their out-of-touch commanders ordering doomed offensives or last stands for the sake of national honor. An average of 6000 soldiers died every day as a result of the advanced technology for killing — machine guns, modern artillery, and poison gas among others — and the lack of sufficient technology to defend against these weapons of war. The brutality of the war caused WWI to be named “the war to end all wars”.

At the close of 1918, Russia had already seen revolution while the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires were on the verge of disintegration. Britain’s Royal Navy blockaded Germany and seized all of its food shipments, starving the German population. The United States joined the war in 1918, with its previously untouched manpower and resources, and forced Germany out of Eastern France and Belgium which it had occupied for the entire duration of the war.

The failed Spring Offensive launched by the German army combined with the subsequent counter-offensive supported by the fresh American troops prompted the German high command to realize that their situation was untenable. They made peace overtures in early October, and the German Revolution that sparked from a sailor’s revolt in Wilhelmshaven led to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s abdication and the proclamation of a German republic.

The terms of the armistice demanded not only for Germany to cease hostilities but to evacuate all occupied territories both in the west and in the recent territories it occupied after Russia and Romania’s defeats in the east. Germany was to decommission all of its submarines and to hand over its battleships to the victorious side. Lastly, Germany at once was to release all prisoners of war while the Entente did not reciprocate this action.

WWI ended with nearly 10 million military deaths accompanied by at least 6 million civilian deaths. Ending the war without completely besting Germany in combat gave rise to the myth of the “stab-in-the-back” of the German army by the civilians who negotiated the armistice.The peace deal given to Germany, the humiliating Treaty of Versailles, strengthened popular discontent to the outcome of the war, stoking nationalist circles. 20 years later, Germany would plunge the world into another world war much more destructive than the last.

Yale holds numerous documents from this important era. The papers of Edward Mandel House, an important diplomat, advisor to President Wilson, and member of the American Versailles delegation, reside within the Beinecke Library. Among the items in the collection is a photograph of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 formed by Woodrow Wilson immediately after the signing of the armistice. The American president sought to enshrine the principles of self-determination and a new international system to preserve peace, promoted in his Fourteen Points and his proposal of the League of Nations. The self-interest of his European allies as well as America’s own refusal to take part in the new international system temporarily doomed his idealism.

Contemporary documents and publications that inform public sentiment are also present in the archive. One insight into the British perspective comes from a volume of the poetry of Wilfred Owen, who used it as a medium to communicate the horrors of modern warfare and the futility of the fighting. His most famous work, Dulce et Decorum est captures these sentiments perfectly.

To this day, whether in France, Commonwealth countries like the United Kingdom and Canada, and the United States, whether the name of the holiday is Armistice Day, Remembrance Day, or Veterans Day, countries still honor the sacrifices made by the individual soldier dying valiantly for their nations and remember that the brutality of the 20th century must not be repeated in the future. Lest we forget.

Bibliography

MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. New York: Random House, 2001.

Owen, Wilfred. Poems by Wilfred Owen with an Introduction by Siegfried Sassoon. London: Chatto & Windus, 1920.

“Paris Peace Conference: Miscellaneous Group Photographs | Archives at Yale.” Accessed November 8, 2020. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/12/archival_objects/1750396.

[Photograph of Emperor Wilhelm II and Empress Auguste Victoria of Prussia]. Gustav Liersch & Co., 1906.

“Photographs | Archives at Yale.” Accessed November 8, 2020. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/12/archival_objects/1750384.

Renesch, E. G. True Blue: World War I Poster: Mother and Children Gaze at Framed Portrait of Husband/Father in Uniform Draped in US Flags above Mantle; Portraits of Presidents Washington, Wilson, and Lincoln Also on Mantle and Wall, 1918.

Wuhrer, L. “Les Principes Du Président Wilson et Les Aspirations Italiennes En Carinthie, Dans La Province de Goritz et En Carniole = The Principles of President Wilson and the Italian Aspirations in Carinthia, in the Provinces of Gorice and Carniola / Lith. L. Wuhr.” L. Wuhrer, 1919.

Tut's Tomb Discovered By Caroline Parker

November 4, 1922

On November 4, 1922, Howard Carter uncovered the entrance to King Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt's Valley of the Kings. The tomb is notable as it was largely untouched by grave-robbers, allowing it to remain intact until Carter and his team combed through the Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun himself was relatively unremarkable. He served as king for approximately ten years after ascending to the throne at a young age. His reign marked the beginning of the restoration of Egypt’s old ways, after a troubled era of changes during Akhenaten’s Amarna Period. His advisers made most of his administration’s decisions.Tutankhamun died unexpectedly around the age of 19, without a designated heir. Despite countless theories about the cause of his death, DNA testing and digital imaging of his mummy have revealed that he likely died of malaria or infection. He was succeeded by his adviser, Ay.

Howard Carter was first introduced to Egyptology while drawing sketches of Queen Hatshepsut’s temple on a British mission to ancient Thebes. He later discovered the tombs of Hatshepsut and Thutmose IV. Carter collaborated with George Herbert, the 5th earl of Carnarvon, to undergo further explorations in the Valley of the Kings. Herbert helped fund the excavations of Tutankhamun’s tomb, which, in full, would take over ten years. However, he did not get to see the excavations completed, as he died of a mosquito bite in 1923. Carter discovered nearly 5,000 artifacts in the tomb, all of which provide archaeologists important information about Egyptian life during the reign of “King Tut” (c. 1333 - 1323 B.C.E.).

The entrance to the tomb was discovered on November 4, 1922, when a boy stumbled over a stone that was actually the top of a flight of stairs. However, Carter did not see inside — holding a candle to a tiny hole in a sealed door—until November 26. The tomb was small compared to others from the same period, and it was likely constructed hastily; however, it was more preserved than any tomb discovered before (or after). Inside, archaeologists found rooms stuffed with furniture, clothes, weapons, chariots, and art. On January 3, 1924, Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus was discovered. His mummy lay within three nesting coffins. The innermost coffin was made of solid gold. The outer two coffins were made of wood with golden gilding. The coffins were decorated ornately. Within, Tutankhamun was adorned with a golden mask, as well as jewelry.

Since the tomb’s discovery, Tutankhamun has become the subject of public fascination. Pictures of the tomb taken by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Harry Burton inspired fashion in the 1920s. Tales about Lord Carnavon’s death and mysteries surrounding the excavation led to theories about a curse on the tomb. The discovery itself influenced pop culture via movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark. The tomb has been in the news more recently, as one of Tutankhamun’s coffins has been recently restored in preparation for a new museum in Egypt. The coffin, which had been inside the tomb since its discovery, had sustained heavy damage due to the temperature and conditions.

Yale collections hold an assortment of materials from this period. The Yale University Art Gallery holds the head of a blue glass sculpture that may depict Tutankhamun dating to his reign, he Beinecke’s papyrological collection includes a scribes writing palette, and the Peabody Museum has several potsherds, including a piece of redware decorated with black spots.

References:

Bressan, David. “Geophysical Survey May Have Found Secret Chambers In King Tut's Tomb.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 21 Sept. 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/davidbressan/2020/09/21/geophysical-survey-may-have-found-secret-chambers-in-king-tuts-tomb/. Accessed 25 Oct. 2020.

Clavin, Patricia. “King Tutankhamun: How a Tomb Cast a Spell on the World.” BBC Culture, BBC, 29 Oct. 2019, www.bbc.com/culture/article/20191029-king-tutankhamun-the-tragic-cause-of-the-pharaohs-cult. Accessed 25 Oct. 2020.

Dorman, Peter F. “Tutankhamun.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 31 Jan. 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Tutankhamun. Accessed 25 Oct. 2020.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 22 June 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/George-Edward-Stanhope-Molyneux-Herbert-5th-earl-of-Carnarvon. Accessed 24 Oct. 2020.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Howard Carter.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 5 May 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Howard-Carter. Accessed 24 Oct. 2020.

“Egyptian Head, Possibly Tutankhamun as the God Amun.” Egyptian Head, Possibly Tutankhamun as the God Amun | Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University Art Gallery, 2020, artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/275886. Accessed 24 Oct. 2020.

Islam, Salma. “King Tut's Coffin Is in 'Very Bad Condition'; Egypt Begins Restoration.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 4 Aug. 2019, www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2019-08-04/king-tut-coffin-bad-condition-egypt-restoration. Accessed 25 Oct. 2020.

“Potsherd, Red Ware, with Black Spots. Toshka East, Tomb I, Time of Tut’ankhamun, 18th Dynasty. 11 Cm. Nubia, Egypt.; YPM ANT 261450,” n.d.

“Yale.Apis.0051830000.” Accessed November 2, 2020. http://papyri.info/apis/yale.apis.0051830000.

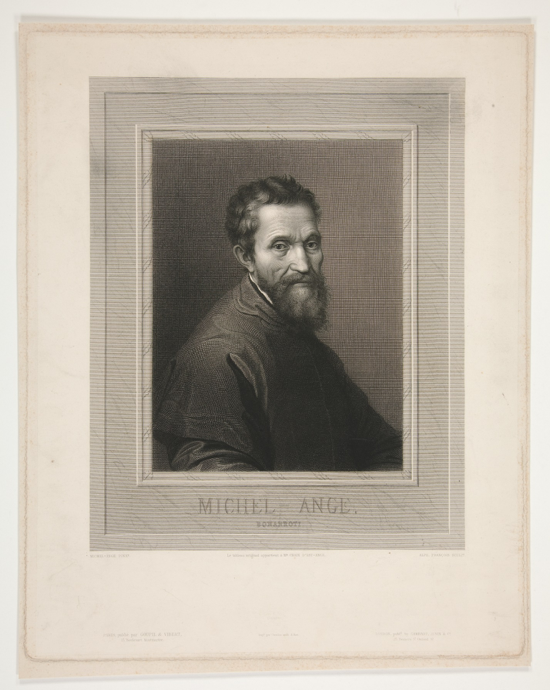

The Sistine Chapel By Daniel Ma

On the first of November 1512, the day of the Feast of All Saints, the Sistine Chapel first opened its doors to the public with its current ceiling. The chapel in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, formally called the Cappella Magna, had been restored from 1477-1480 under Pope Sixtus IV (hence the name) but was now undergoing major stylistic changes. Yale’s art gallery has the architectural slides for the restored chapel, and all can go and view the famous chapel as initially planned, three decades before it took its most famous form.

From the beginning of the restoration, the chapel was handled by only the best artists in Italy, many still household names today. Between 1481 and 1482, noted masters of the Early Renaissance Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio (Michelangelo’s teacher) and Cosimo Rosselli led the initial restoration, painting the four walls of the chapel in brilliant fresco. Portraits of the popes ran around the wall, with stories of Christ and Moses in panels along the north and south walls, respectively, wrapping around to the altar and entrance walls. The original ceiling was a simple starry sky, painted by Matteo d'Amelia. The chapel was consecrated on August 15th, 1483.

An ensuing pope, Julius II, decided to change the décor of the chapel by repainting the ceiling and adding lunettes on the tops of the walls after a crack developed in the old ceiling in 1504. He enlisted the most famous artist in Italy at the time, Michelangelo, who was also commissioned to make a monumental tomb for Julius II, which ended unfinished but included the masterworks of an enormous, life-like horned Moses and unfinished sculptures of slaves that show priceless insight into Michelangelo’s work process. It appears, according to the contemporary Giorgio Vasari, founder of art history, that the project to paint a fresco, so far out of his domain, for an employer he could not refuse, was an attempt by Michelangelo’s rivals, Raphael and Bramante, to make him fail.

Instead, Michelangelo created arguably the greatest work of art ever over a four year stretch from 1508-1512. Nine central panels depict the story of Genesis, from creation through man’s rebirth in the story of Noah. Twelve prophets and sibyls and Christ’s forefathers surround the central scenes in spandrels and lunettes, with each corner having a pendentive containing an instance of God saving Israel. The images of Eden have resonated through the ages—the hunched figures of Adam and Eve being banished, the eating of the forbidden fruit from the serpent, and most of all, the oft-reproduced limp hand of Adam nearly touching the pointing hand of God in Creation of Adam. These images have come all the way to our present day, the culmination, the cultural product of those slides we can view in our art gallery today.

Of course, the story of the Sistine Chapel did not end with its opening. The entrance wall was repainted after the door of the chapel collapsed in 1522. Then, from 1536-1541, an old Michelangelo returned to the site of his greatest work and produced another masterpiece: The Last Judgement, a single massive fresco covering the entire altar wall, now in the Late Renaissance style and approaching Mannerism with the contortions and exaggerations of the figures in pain. Christ judges all, with the saints watching, and the naked figures are sent to their various dooms by Minos and Charon, in accordance with Dante’s Inferno. The gloomier scene reflected both Michelangelo’s age and the growing trends of the Counter-reformation in attempting to emphasize the importance of Catholic religious fervor and judgement — Michelangelo’s two stints working on the chapel were separated by the Reformation’s beginning in 1517. And finally, a series of controversial restorations from 1979 to 1999 removed much of the dirt and grime accumulated from centuries of candle smoke but arguably diminished some of Michelangelo’s original vivid colors and details—a debate that will never end.

Bibliogrpahy

Panofsky, Erwin. “The First Two Projects of Michelangelo’s Tomb of Julius II.” The Art Bulletin 19, no. 4 (1937): 561–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045700.

“Portrait of a Lady with a Rabbit | Yale University Art Gallery.” Accessed November 2, 2020. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/334.

“Portrait of Michelangelo | Yale University Art Gallery.” Accessed November 2, 2020. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/113808.

“Sistine Chapel.” Accessed November 2, 2020. http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/cappella-sistina/storia-cappella-sistina.html.

“Sistine Chapel | Archives at Yale.” Accessed November 2, 2020. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/5/archival_objects/2522043.

“The Prophet Isaiah, from the Series Sibyls and Prophets from the Sistine Chapel Vaults | Yale University Art Gallery.” Accessed November 2, 2020. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/121746.

“Vasari’s Biography of Michelangelo.” Accessed November 2, 2020. http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth213/michelangelo_vasari.html.

“Virgin and Child | Yale University Art Gallery.” Accessed November 2, 2020. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/309.

The New York City Subway By Daniel Ma

The New York City subway, by far the largest and most widely-used American subway system, first opened on October 27th, 1904. The initial subway had a single line running from City Hall in Lower Manhattan to 145th Street and Broadway in Harlem. Train cars were initially quite lavish and played to the tastes of fascinated New Yorkers willing to try the new system over the old streetcars, street-level railways, elevated lines (the “el,” as they were called), and buses. Passengers paid a nickel fare to take the subway for any distance. The silent video here was taken in 1905 and shows a car from the original batch travelling between 14th and 42nd streets, moving through tunnels, also providing rare images of the original stations while the train pauses for passengers to embark and disembark.

An earlier 312-foot tunnel under Broadway had been made in 1870 as a demonstration for a potential subway system, but objections by landowners who preferred the el (the first of which also opened in 1870) along with the Panic of 1873 torpedoed the proposal. Interestingly, that subway had been powered by an enormous fan blowing the subway cars down a tube in which they were carried—a design the actual subway abandoned in favor of normal train cars.

At the time, the subway was run privately under the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) company, whose lines eventually became the numbered lines of the subway system today of “IRT.” The IRT had previously made the elevated lines that were the main system of quick transportation in the city before the subway. Extensions to initial service came rapidly. Within a month, service was extended further north and the east side branch was opened, also to 145th street. By the following year, service had reached the Bronx, fulfilling the “Interborough” of the company’s name. In the next decade and a half, the paths and stations of the west side and east side IRT lines very closely resembled the modern 1/2/3 and 4/5/6 lines, and all the boroughs were serviced with the exception of Staten Island. These two IRT lines alone take 2.5 million of the 5.5 million daily passengers on the NYC subway today, each taking more passenger traffic than any other American city’s entire metro system.

A rival company to the IRT, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT), began in 1915, taking passengers between Brooklyn and Manhattan. This was soon acquired by the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT). The BMT emphasized its relatively more comfortable cars and focused on tourism more so than rapid transit, connecting its subways to preexisting lines to Coney Island and Brighton Beach. Then, in 1932, the city opened the Independent Rapid Transit Railroad, or IND, and established the first public subways in the city. The IRT and BMT were bought by the city in 1940 during the Great Depression as the system struggled and service worsened in quality. Refusing to bow to political pressure, the city doubled the nickel fare in 1948 after 44 years, the struggle being one of the main reasons it made a single and separate public corporation, the NYC Transit Authority, for the subways in 1953. Hence began the modern MTA that has since expanded its scope also to buses, bridges and tunnels, and commuter rail—including the Metro-North that Yalies take to New Haven.

The legacies of the early transit system can still be seen today, a century later. The IRT/BMT divide persists, as the numbered lines are IRT and the lettered lines are BMT or IND. The numbered and lettered lines have different rail gauges, different tunnel widths, and different station lengths, a reminder that the subway system started with a disunified series of private companies. While the nickel fare is long gone, the subway has retained its tradition of charging the same amount for trips of any distance, unlike many other systems around the world. Even the old City Hall station, the inaugural station opened on that day 116 years ago, is still present; it sits along a loop of track where empty trains change direction at their present terminal at the new City Hall station. New Yorkers may malign the subway, but it is still dear to our hearts.

Bibliography

APTAAdmin. “Ridership Report.” American Public Transportation Association (blog). Accessed October 24, 2020. https://www.apta.com/research-technical-resources/transit-statistics/ridership-report/.

“Feb. 26, 1870: New York City Blows Subway Opportunity.” Wired. Accessed October 24, 2020. https://www.wired.com/2010/02/0226new-york-pneumatic-subway/.

Gavrielov, Nadav. “The Subway Fare Rises on April 21. It Could Be Worse: One Year It Doubled. (Published 2019).” The New York Times, April 12, 2019, sec. New York. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/12/nyregion/mta-fare-hike.html.

New York Transit Museum. “Home.” Accessed October 24, 2020. https://www.nytransitmuseum.org/.

Interior NY Subway. New York at the Turn of the Century. American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, 1905. https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/interior-ny-subway.

“Mta.Info | 110 Years of the Subway.” Accessed October 24, 2020. http://web.mta.info/nyct/110Anniversary/history.htm.

New Map of New York City. From the Latest Surveys Showing All the Ferries and Steamship Docks, Elevated, Subways Electric and Cross Town Car Lines. c 1900. Map. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/4204898.

Steinberg, Saul. [Two Women and Man (Subway)]. 1946. Sketch. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3481462.

Van Vechten, Carl. New York City. Manhattan. Sixth Avenue. View of a Subway Construction Worker. August 25, 1937. Photograph. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3538061.

“World’s Oldest Metro Systems - Railway Technology.” Accessed October 24, 2020. https://www.railway-technology.com/features/worlds-oldest-metro-systems/.

Opening of the Erie Canal By Caroline Parker

On October 26, 1821, the Erie Canal was completed. This feat of engineering caused an increase in westward migration and made trade west of the Appalachian mountains easier and more accessible than it had been previously. Construction began on the site in 1817 -- although there were reportedly plans to construct such a canal as early as 1768. New York Governor DeWitt Clinton advocated heavily for the project, first as a state senator and later as the mayor of New York City. When the federal government refused to supply the necessary funds, he convinced the state legislature to authorize $7 million of loans to support construction. When it was in its early stages of development, the canal was jokingly called “Clinton’s Big Ditch.” The canal was ultimately an immediate success, though, lowering transportation costs, attracting settlers, and cementing New York City as a hub of commerce.

The canal stretches 363 miles from Albany to Buffalo, connecting Lake Erie to the Hudson River. At the time of construction, it was 4 feet deep and 40 feet wide; however, it has been enlarged three times since. The canal featured 83 locks -- today 57 -- and an elevation change of 570 feet. In 1825, it was a marvel, and the canal remains impressive to this day, especially because it was built without the help of a single professionally trained engineer. At the time, only West Point offered an engineering program; however, several engineering schools, including Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, were founded in response to the project. Additionally, the engineers trained on this project applied the knowledge they gained to multiple canal and railroad construction works in the next decades. Work was divided between several small contractors who provided their own labor, equipment, and supplies. Laborers were paid little, typically somewhere between 80 cents and 1 dollar per day.

Goods were transported in both directions along the canal in mule-pulled canal boats. The price of shipping goods from Buffalo to New York City shifted from $100 per ton to less than $10 per ton. People could travel more quickly -- traveling from Buffalo to New York became a 5 day trip, rather than the previous 14 day expedition. Ideas also traveled freely around the canal, which saw the First Women’s Right Convention at Seneca Falls in 1848 and religious revivalism in the 1820s and 1830s with the Second Great Awakening. Paths along the canal were also utilized in the Underground Railroad, as many locals were outspoken abolitionists. It should be noted that despite these benefits, the construction of the Erie Canal disrupted the lives of Native Americans who called the region home. Construction occurred at the same time as several “Indian removal” policies, which moved Native Americans to remote reservations, typically in the Midwest.

On October 26, Governor Clinton and his party boarded the Seneca Chief to travel from Buffalo to New York City. Upon his arrival in New York eight days later, Clinton ceremoniously dumped water from Lake Erie into the Hudson River, calling it a “marriage of waters.”

Today, the New York State Canal System is the oldest continually operating transportation system in North America. Traffic on the canal has shrunk significantly since 1825, as more rapid transportation systems have grown, and much of the canal is now dedicated to multi-purpose recreation and parks.

Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library houses two well-preserved maps of proposed routes for the Erie Canal dating from 1811 and 1821.

Works Cited

“History and Culture.” Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, 2020, eriecanalway.org/learn/history-culture. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Maverick, P. “Map of the Western Part of the State of New York Shewing the Route of a Proposed Canal from Lake Erie to Hudson’s River Compiled by John H. Eddy from the Best Authorities 1811.,” n.d. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/4206595?image_id=15790140.

Robb, Frances C. “Erie Canal.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 11 Mar. 2020, www.britannica.com/topic/Erie-Canal. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Sadowski, Frank E. “The New York State Canal System.” New York State Canal System, The New York State Canal Commission, 2012, www.eriecanal.org/system.html. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

“Today in History - October 26.” The Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/october-26/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

The Accession of King George III By Jeremy Sontchi

October 25, 1760- All across the United Kingdom of Great Britain, church bells rang and mourning services were planned. Their king of the past 33 ears, George II, had passed away on the toilet in the early morning. To take his place, the nation turned towards his young grandson, 22 year old George William Frederick of the House of Hanover. He would reign under the name George III for almost 60 years until his death on the 29th of January, 1820. To this day he remains the oldest and longest reigning King of the United Kingdom and only eclipsed by Queens Victoria and Elizabeth II. His reign also saw some of the greatest shifts in British political and economic life, including the loss of the American colonies, the Act of Union of 1801 unifying the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, the defeat of Napoleon, and the early beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

When George III was officially crowned on September 22, 1761, he broke a long pattern of the British monarch being foreign-born. His two predecessors, George I and George II, had both been born and raised in Hanover. As such, neither were fluent or familiar with the English language or its customs. George III was different. The grandson of George II, he was born and raised in London, making him the first Prince of Wales born in England since 1630. This was a fact he was well aware of. At 10, he performed a new prologue for Addison’s Cato, saying “What, tho' a boy! It may with truth be said, A boy in England born, in England bred.”

The accession of George III also brought about a radical shift in royal finances. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William and Mary were granted a yearly revenue of approximately £700,000 to help defray the costs of funding the civil government, including the salaries of the civil service, ambassadors, judges and the royal household, which had previously been entirely paid by income from the hereditary lands of the monarch. Following the financial difficulties of George III in the last years of his reign, Parliament passed the Civil List Act of 1760. Under this law, George III willingly surrendered all income from his hereditary properties to Parliament in exchange for a fixed yearly salary of £800,000 for the maintenance of the royal household and government assumption of responsibility for funding the civil government.

Even to this day, George III is still known to most people as the king who lost America. In large part this is due to the writing of contemporary American patriots, who described him as “a royal brute” and accused him of wishing to enslave his American subjects. As a target of vitriol for the rebellion, King George was an odd choice, having little to no involvement in the ire inducing Stamp, Townshend, and Quartering Acts or most other grievances named in the Declaration of Independence. Relatively detached from politics and previously uninterested in America, his role in the American Revolution was mostly limited to raising volunteers and morale visits to troops.

In 1786, George III faced a challenge to his rule of a different sort than the American Revolution. Margaret Nicholson, a former housemaid, approached His Majesty at the entrance of St. James’ Palace on the 2nd of August bearing a piece of paper as if it was a petition. However, the paper was blank and when he approached to receive it she stabbed at him twice with a dessert knife. He dodged the first stab and received a glancing blow from the second before she was subdued. Feeling that the attack was poorly planned and only half-heartedly attempted and that Ms. Nicholson might be in danger from an angry crowd or his guards, he shouted “The poor creature is mad; do not hurt her, she has not hurt me.” She was arrested and brought in front of the privy council, as opposed to the normal practice of trial by jury for treason, on the prerogative of the king. There an investigation revealed that she had produced substantial writings claiming to be the rightful monarch and that “England would be discharged with blood for a thousand years if her claims were not publicly acknowledged.” On this basis, she was declared insane and sentenced to life in Bethlem Hospital. This represented a substantial show of clemency from King George as she could have expected death for treason if he had not exercised his power to try her in the privy council and once found guilty, she would have normally been expected to be held in a gaol. Not guilty by reason of insanity would only appear as a verdict in 1800, again for an attempted assassination of King George III, but on that occasion by James Hadfield. Following fears that insane criminals could be let free, Parliament passed the Criminal Lunatics Act of 1800, which dictated that all those found not guilty by reason of insanity be detained at the pleasure of the king, most often in gaol or a madhouse.

Along with the loss of America, King George is also remembered for his madness late in life. Characterized by mania and hypothesized to have been the result of porphyria or bipolar disorder, he suffered a severe episode in 1788 which manifested in him “sleeping badly, hoarse with relentless talking, unsteady on his feet, mentally confused, and occasionally violent.” The primitive nature of medical knowledge and treatments for mental at this time meant that his doctors’ primary remedy was what he ruefully referred to as his “coronation chair,” a restraining chair that he would be locked into until his mania subsided. The prevailing theory of his illness at the time was that he had bad humors in the legs, possibly the result of not promptly removing wet stockings. This illness also sparked off a political controversy as members of the government considered whether the condition was severe enough to justify a regency by George, Prince of Wales (later George IV), a question that involved significant political implications around the Prime Minister. The House of Commons passed a Regency Bill in 1789 which was set to come into force on the 20th of February. Just three days before then, George III recovered and praised the government for acting correctly in his debilitation to work towards appointing a Regent. 20 years later, in 1810, he became very ill again and, accepting the necessity of a regent, had his son, George, Prince of Wales (later George IV), take the regency under the auspices of the Regency Act of 1811 until his death in 1820.

Bibliography

Cannon, John. “George III (1738–1820), King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and King of Hanover.” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press, September 23, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/10540.

Eigen, Joel Peter. “Nicholson, Margaret (1750?–1828), Assailant of George III.” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Accessed October 24, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/20145."William III, 1697-8: An Act for granting to His Majesty a further Subsidy of Tunnage and Poundage towards raiseing the Yearly Su[m]m of Seven hundred thousand Pounds for the Service of His Maj[es]ties. Household & other Uses therein menc[i]oned dureing His Majesties Life. [Chapter XXIII. Rot. Parl. 9 Gul. III. p. 4. n. 5.]," in Statutes of the Realm: Volume 7, 1695-1701, ed. John Raithby (s.l: Great Britain Record Commission, 1820), 382-385. British History Online, accessed October 24, 2020, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol7/pp382-385.

Annie Edson Taylor By Taylor Barton

On October 24th, 1838, Annie Edson Taylor was born in Auburn, New York. On that same day in 1901, at 63 years old, she would become the first person to successfully complete the journey over Niagara Falls in a barrel.

After a life full of money troubles and unfortunate circumstances, in 1901, Taylor began looking for a way to earn money fast and improve her situation. In addition to supporting herself, she was also supporting two of her friends who were in need, along with both of their families. One day whilst reading the newspaper, she discovered that the Pan-American Exposition of 1901 would be held very close to her in Buffalo, New York, and that people were expected to flock to Niagara Falls afterwards. Inspired by the daredevils and street performers that came before her, she quickly came up with the idea to "Go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. No one has ever accomplished this feat.” She planned that a crowd would gather during her stunt and a collection would start, but beyond this thought, no actual planning went into making a profit off of her daring feat.

Once she decided to attempt this stunt, she began doing research. Many before her had attempted to conquer the falls, but most died, and none of them thought to make the journey in a barrel. Determined to increase her likelihood of survival, Taylor began designing her own barrel out of Kentucky Wood, fit with harnesses and cushions for her protection, which was eventually custom made by Bocenchia, a local business.

The planning began in August, and by October, Taylor and her barrel were both ready to make history. On October 24th, Taylor got into her barrel and entered the water at the head of Grass Island where her journey began. From here, she would travel one mile through the rapids until she reached Horseshoe Falls, a trip that ultimately took 20 minutes to complete. She described this portion of the journey as “pleasant,” after she recovered from the initial fear of suffocation. She was able to calm herself by praying and reminding herself to be brave. The trip was smooth until the barrel arrived at the end of the falls. She claims that “it was then [she] began to suffer.” She was fully submerged for a time after striking the water, a time which she describes as being completely silent. After the silence came the violence, as the barrel became caught in the thrashing water at the bottom of the falls. The barrel was thrown harshly against rocks, shaking Taylor roughly inside. Finally, after 17 minutes of terror, just as she began to lose consciousness,Taylor’s barrel was pulled from the water.

The rescue effort was headed by John Ross, Chief Engineer of the “Maid of the Mist,” and Mr. Williams, a Canadian Civilian. They found a wrench and promptly opened the barrel to retrieve Taylor. Ross was so shocked when he discovered Taylor alive that, according to her, he exclaimed, “The woman is alive!” to which she responded “Yes she is, though much hurt and confused.” While she had suffered both a minor head injury and shock during her journey down Niagara Falls in a barrel, she ultimately survived, making headlines as “The first and only human being who has made this fearful leap over the falls and lived to describe it.” While she gained temporary fame for her stunt, she unfortunately did not receive the financial compensation she was expecting.

In the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale has a photo of Horseshoe Falls from 1900, taken only one year before Taylor made her iconic journey down that very same stretch of Niagara Falls.

Works Cited

Horseshoe Falls, Niagara. 1900. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3434554. Accessed 10 Oct. 2020.

Taylor, Annie Edson. Over the Falls. Annie Edson Taylor, 1902. Core, Annie Edson Taylor, core.ac.uk/download/pdf/62641078.pdf.

"Went over the Falls." Wellsville Daily Reporter [Wellsville], 15 Oct. 1901. Rare Newspapers, www.rarenewspapers.com/view/591022. Accessed 10 Oct. 2020.

The Battle of Sekigahara By Louie Lu

On October 21st, 1600, the forces under Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated its opponents, loyalists to the Totoyomi clan, at Sekigahara. This victory allowed the ascendant Tokugawa clan to establish a shogunate (bakufu), a military government that traditionally ruled in place of the Emperor, a regime that ensured peace in Japan for more than two and a half centuries.

The previous Ashikaga shogunate proved unable to assert central authority over their vassal daimyos, powerful clans that controlled entire regions of the realm. The autonomous daimyos began to wage war on each other to expand their territory, with a dispute between the Hoshikawa clan and Yamana clan in 1467 beginning an era of constant internecine conflicts, named the sengoku jidai or the Era of Warring States. Amidst the strife rose the Oda clan, whose head Oda Nobunaga would defeat the most powerful clans. While Nobunaga’s sudden betrayal by a retainer halted his ambitions for power, another one of his followers, Totoyomi Hideyoshi, managed to completely unify Japan. Hideyoshi implemented a series of administrative reforms that brought stability to the country.

Yet, Hideyoshi was never able to assume the title of Shogun nor ensure a stable succession due to his lowly birth. His death at 62 left his young son in the regency of the five most powerful lords of Japan, one of which being Ieyasu. The death of the most respected regent led to the development of two factions divided along territorial lines. The eastern lords supported the powerful Ieyasu while the western lords wished to prevent the young Totoyomi Hideyori from being supplanted. A failed assassination attempt on Ieyasu’s life and the refusal of one of the daimyos to demilitarize led the two factions to fight.

The western lords, led by Ishida Mitsunari, managed to capture some fortresses initially and marched to Gifu castle, whose control would have allowed them to advance on the capital. Unfortunately, the eastern forces of Tokugawa had recently dislodged the castle from the loyalists, and Mitsunari ordered his forces to retreat south to take a defensive position near the town of Sekigahara.

While the loyalists were outnumbered by the Tokugawa forces, Mitsunari attempted to use the mountainous terrain of Sekigahara and superior positions to trap their opponents. However, unbeknownst to him, Ieyasu had been secretly contacting some of the western lords, securing their defection. Ieyasu ordered his advance guard to charge the loyalists’ right flank, and one of the key loyalist defenders there chose at that moment to defect, leaving the flank vulnerable. Continued Tokugawa successes caused more western daimyos to defect, allowing Ieyasu to destroy the right flank and push back the center. Isolated, Mitsunari could only await defeat.

Ieyasu’s victory cemented his primacy in the land, confiscating territory from the defeated enemy and rewarding his supporters. He also executed Mitsunari while allowing for Hideyori to reside in Osaka castle as a show of leniency.

The Emperor in 1603 granted the title of shogun to Ieyasu, creating the Tokugawa shogunate. Ieyasu would maintain the reforms of his predecessors, maintaining the strict caste system implemented by Hideyoshi while implementing the policy of sakoku, diplomatic isolation for Western powers. The 260 years of peace brought by the Tokugawa shogunate coincided with increased urbanization and the development of a merchant class in Japan. Tokugawa rule would end in 1868 when the arrival of foreigners provided an opportunity for the Emperor to reassert his authority in what would be known as the Meiji Restoration.

Bibliography

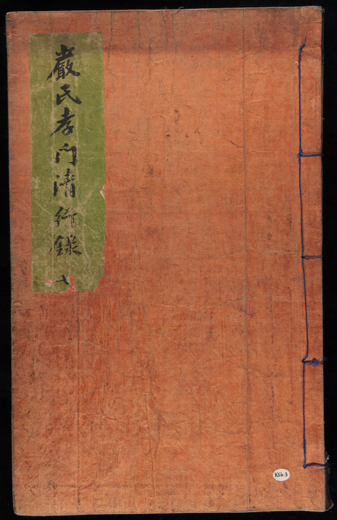

Tokugawa Ieyasu shuinjōan. Yale Association of Japan Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

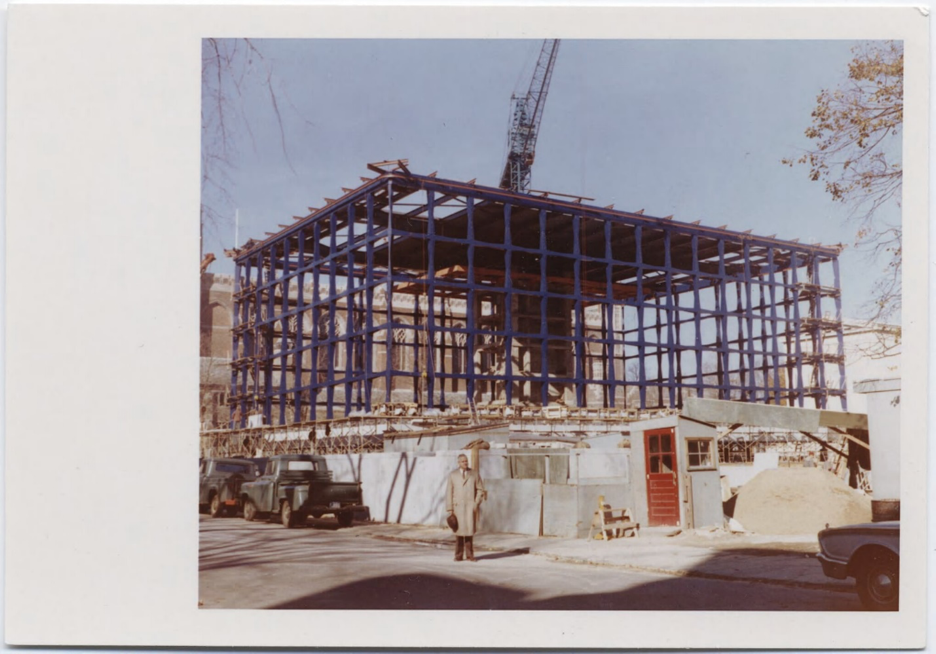

The Opening of the Beinecke Library By Jeremy Sontchi

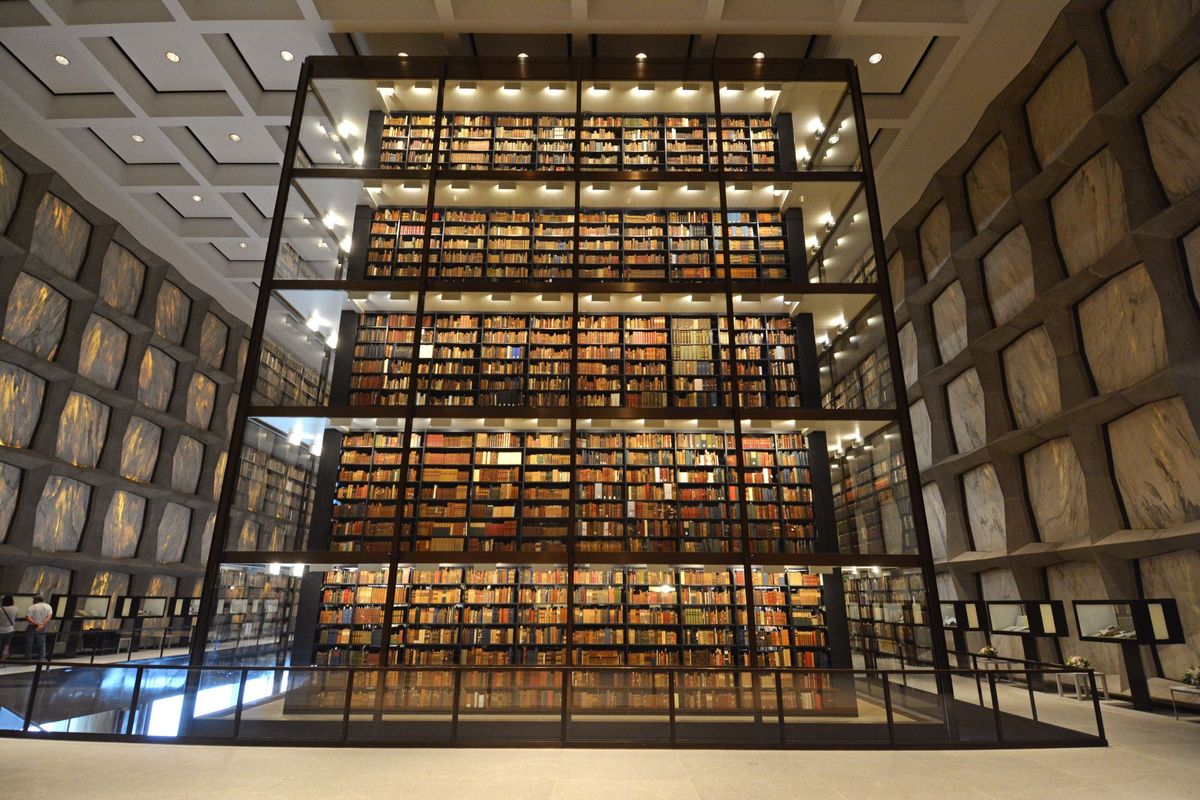

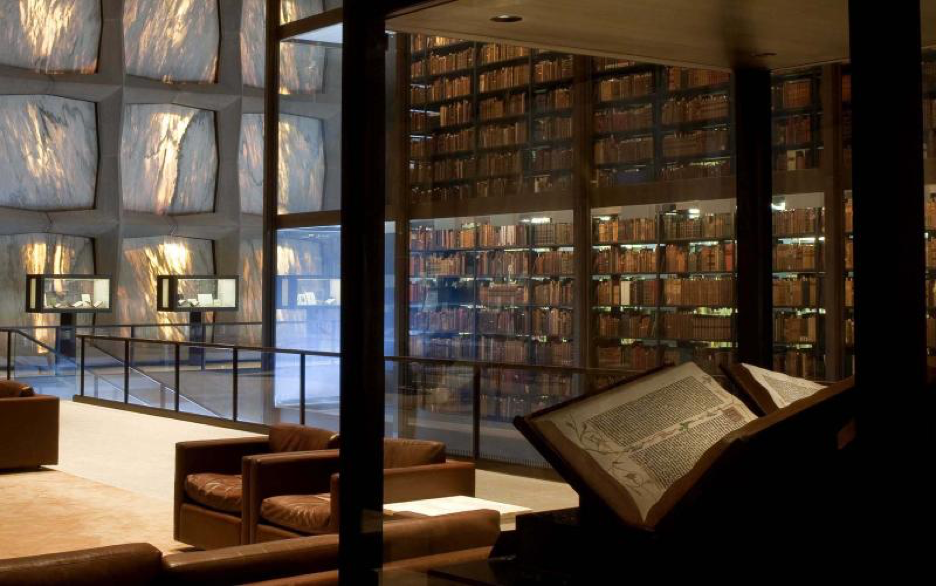

October 14, 1963- The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library was officially opened at Yale University. One of the largest rare book and manuscript libraries in the world, it is the primary location for Yale’s literary archives, rare books, and delicate materials.

Designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill and the gift of three brothers and Yale alumni, Edwin J. Beinecke (1907), Frederick W. Beinecke (1909), and Walter Beinecke (1910), the library attracts over 200,000 visitors a year. The vast majority of these visitors do not come for the collections but instead for the stunning architecture. Located within the neoclassical Hewitt Quadrangle, the box-like and stark white Beinecke is highly conspicuous. From the outside, it is an elevated rectangular prism covered in white stone panels running five tall, ten wide, and fifteen long, forming a 1:2:3 ratio in honor of the materials within as many early books and manuscripts are laid out in this same ratio.

On the inside, these panels display their true beauty as the one and one quarter inch thick slabs of Vermont white marble are translucent, allowing the sunlight to fluoresce through with a golden glow. The marble plays a crucial function in the library’s design. It does not just change the color of the light but also filters out harmful spectra that could damage or degrade objects inside. The inside of the library is a vast cathedral-like exhibition hall split into two levels and dominated by a six-story glass-enclosed book tower. This book tower holds roughly 180,000 books and there is room for another million books in underground storage. It is commonly said that the library stacks contain a fire suppression system so extreme that it will kill anyone within them by removing all the oxygen. This is false. While the original system called for carbon dioxide, it has since been replaced over personnel safety concerns with a mix of inert gases which lower the percentage of oxygen to a non-fatal level. The Beinecke book tower has also been the home of innovation in pest control. The library invented the process of freezing books at -20℉ for 36 hours to control bookworm infestations following an infestation in 1977. The process is now widely used in archives around the world. Around the tower are the exhibition floors which hold items on permanent and temporary displays.

The permanent display consists of two items: an original and complete Gutenberg Bible and the Double Elephant Folio of John James Audubon’s Birds of America. The first printed book in the world and an excellent example of the beauty of textual illumination, Yale’s Gutenberg Bible is one of only five perfect copies in the United States and one of only 49 copies of any quality existing in the world from the original printing. Both of its volumes sit in the case, open for viewing. Across the hall from the Gutenberg bible sits Yale’s copy of Audubon’s Double Elephant Folio. This monumental work is a printing of John James Audubon’s famous Birds of America, a documentation of the avian wildlife of the continent. Both of these works remain safe in climate controlled cases but if you visit over long enough periods, you will see different images. Four times a year, the pages are flipped as a part of the larger rearrangement of the temporary exhibitions.

Alongside the temporary and permanent exhibitions, the Beinecke contains an extensive selection of reading and seminar rooms below ground to facilitate access to the collections for registered readers. A non-circulating collection, all materials must be used on the premises under observation. While this might seem excessive, these security measures are very important as the value of the collections make them an alluring target for theft. In 2005, Edward Forbes Smiley III was arrested in New Haven, CT for theft. After a librarian noticed an X-Acto blade on the floor of the Beinecke reading room, Mr. Smiley, a rare maps dealer, was stopped and discovered to have seven maps on his person that he had cut out of rare books with his knife. A single map he had was worth over $150,000 and his total career haul of 97 maps, stolen from a variety of academic and public collections, was worth more than $3,000,000.

Sources:

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. “About the Building,” December 14, 2018.https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/about/history-and-architecture/about-building.

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. “History and Architecture,” December 20, 2018.https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/about/history-and-architecture.

James, Kathryn. “Seeing the Gutenberg Bible and The Birds of America.” Text, March 31, 2018.https://beineckegutenberg.yale.edu/news/seeing-gutenberg-bible-and-birds-america.

“Rare Bookman - The New York Times,” June 14, 2018.https://web.archive.org/web/20180614090048/https://www.nytimes.com/1978/06/11/archives/rare-bookman-gallup.html.

“The Double Elephant Folio | Audubon at Beinecke.” Accessed October 4, 2020.https://beineckeaudubon.yale.edu/news/double-elephant-folio.

“The Gutenberg at Beinecke.” Text. Accessed October 4, 2020. https://beineckegutenberg.yale.edu/.

Tidmarsh, David, Feb 04, and 2010. “Myths Abound about Beinecke.” Accessed October 4, 2020.https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2010/02/04/myths-abound-about-beinecke/.

The Battle of Hastings By Louie Lu

On October 14th, 1066, the Normans under the leadership of William the Conqueror decisively defeated England at the Battle of Hastings. This battlefield success translated into Norman conquest of the entire English kingdom.

The previous Anglo-Saxon King of England, Edward the Confessor, died heirless at the start of 1066. Previously, Edward had declared William, the bastard Duke of Normandy, as his heir, yet at his deathbed he decided to that the crown would instead go to the most powerful English noble in his realm, Harold Godwinson, the Earl of Wessex. Immediately after Harold’s ascension to the throne, his rule was contested by two neighboring kingdoms. To the south William protested that Edward had originally promised him the throne while the Norwegian King Harald Hardrada prepared a large invasion force to press his own claims.

The Norwegians first landed in the north, reaching as far as York. Harold retaliated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in late October and drove Hardrada’s forces off English soil. However, he had lost a significant number of his soldiers here.

Upon learning that the Normans too had landed in the south of England, Harold force-marched his forces across the kingdom. His already-exhausted troops managed to accomplish the task within three weeks, arriving at William’s newly-built fort at Hastings. The English army, which was composed almost entirely out of infantry including professional retinues of soldiers known as housecarls, took up a defensive position at Senlac Hill. On the other hand, the Norman army that was only half infantry with the other half containing heavy cavalry and archers opted to attack, hoping to break through the enemy infantry.

Contrary to Norman expectations, the English formations remained steady and rendered the Norman cavalry charges ineffective. As the Normans retreated, seemingly broken from the failed attack, some English soldiers sensing blood would rush forward to capitalize on perceived enemy weakness only to find themselves victims of feigned retreats. As a whole, the battle lasted the entire day without either side achieving a clear advantage.

Near the end of the battle, Harold Godwinson took an arrow to his eye and fell in battle, and his demoralized troops soon lost the will to fight. William soon took London and was crowned King of England after defeating another pretender from the house of Wessex, and he would continue to crush localized noble resistance later on in his reign. Norman rule coincided with a dramatic increase in construction of castles and keeps for them to retreat into whenever a rebellion did break out.

Punishing his opposition and rewarding his military supporters, he confiscated the lands of English nobles and redistributed them to Norman followers, resulting in the replacement of the vast majority of England’s ruling class (and the English nobility’s dogged determination to raise rebellions). In just a short period of time, nearly all governmental and ecclesiastic offices would be held by Normans. In fact, the nobility ceased to use English altogether, with French and Latin dominating the court. William and his descendants also preferred to spend most of their time in Normandy, securely ruling England from afar.

Despite the demographic changes in the elite, adopted and developed on the more existing administrative and legal system of England which was more complex than that of Normandy. William saw his two titles as distinct; he could be a vassal of the French crown as the Duke of Normandy and simultaneously be an equal as the King of England. Likewise, he respected the laws implemented by his past kings, especially that of Edward. The Beinecke holds a manuscript that “includes a copy of the charter in Old English presented by William the Conqueror to citizens of London, affirming the laws and rights they held Edward the Confessor.”

The Norman conquest had greater impacts than the integration of French words into the English language. For the next four centuries, English kings with numerous holdings in France would create continuous conflicts between the two neighbors, culminating in the destructive Hundred Years War in the 14th century.

Sources

Osborn fa31 A Copie of the grants of the liberties of the Eyre of London.London, England; early sixteenth century (during the reign of Henry VII). Parchment; 22 ff.; 750 x 290 mm.; 1 column. Dry-point ruling. https://pre1600ms.beinecke.library.yale.edu/docs/pre1600.osborn.fa31.htm

The Founding of Yale By Jeremy Sontchi and Taylor Barton

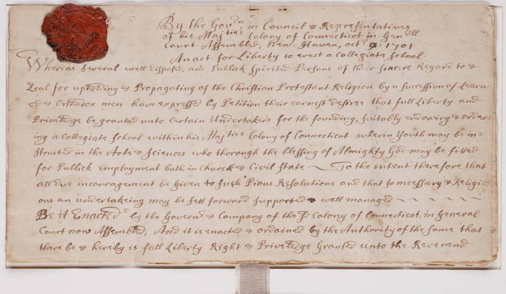

OCTOBER 9, 1701- Fitz-John Winthrop, Governor of the Colony of Connecticut, approves “An Act for Liberty to Erect a Collegiate School,” the school that would later become known as Yale University.

This “Collegiate School” was the dream of Reverend John Davenport, a founder and leader of the New Haven Colony in the late 1600s. He wanted to create a college in New Haven to educate future leaders in the arts and sciences to prepare them for careers in religion and politics inspired by the example of the New College, later known as Harvard University, in Massachusetts and the College of William and Mary in William Mary. Unfortunately, his goal was not accomplished until after his death, when his successor Reverend James Pierpont advocated for the creation of the school. The school’s charter emulated the desires of Davenport, laying out an institution such that “Youth may be instructed in the Arts & Sciences who thorough the blessing of Almighty God may be fitted for Publick employment both in Church & Civil State.” With an official charter granted by the legislature, the Collegiate College began educating in the home of Yale’s first rector and president, Abraham Pierson. While the charter called for the location to be Saybrook. Reverend Pierson’s congregation was opposed to his leaving and, as such, he taught from his home in Killingworth. Upon his death in 1707, the school moved to Saybrook, yet just 9 years later in 1716, the school moved again to New Haven, Connecticut. It was after this move in 1718 that Elihu Yale made a generous donation to the budding college, and the Collegiate College was renamed Yale College in his honor.

Since then, Yale has undergone many changes and transitions that make it the school it is today. A great deal of these transitions expanded the diversity of the once homogenous student population and changed the meaning of what it meant to be a Yale student. At the beginning, the Collegiate school was explicitly limited to male students of Congregationalist orthodoxy. In the past three centuries, the student body has vastly expanded in both size and diversity. In 1854, Yung Wing was not only the first student of Chinese ethnicity to graduate from Yale, but also the first person of Chinese descent to graduate from any American university.In 1874, Edward Bouchet was the first African American to graduate from Yale. Two years later, he also became the first African American to earn a doctorate degree at an American University.

The establishment of gender diversity among the student body also represented a long process. In 1869, the Yale School of Fine Arts was opened as a coeducational school, with two women enrolling in the first class. 15 years later, the Yale Law School accidentally accepted a woman, Alice Rufie Blake Jordan, who applied with her initials. While she was allowed to complete her degree, after her graduation course enrollment was explicitly limited to men, with a repeal only occurring in 1919. In 1892, women were first admitted to the Yale Graduate School and, finally, in 1969 women were admitted into Yale College for undergraduate studies.

Yale’s early mission to educate future leaders has carried on through the years, as five US presidents have attended Yale, as well as a myriad of very successful people in every field. However, while the goal to educate has remained, Yale has changed significantly over the years. The original charter for the Collegiate School of Connecticut can be found in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where it serves as a reminder of how greatly Yale has evolved from its humble beginnings in a house to the renowned institution it is today.

Hangŭl By Louie Lu

On October 9th, 1446, King Sejong the Great introduced the newly-created Hangŭl alphabet to the Joseon kingdom. Today, Hangŭl is the official writing system on the Korean peninsula. The

Before the adoption of Hangŭl, Korea primarily used traditional Chinese characters, Hanja, as their primary script due to its historical cultural ties with the neighboring civilization, and the spreading Buddhist and later Confucian ideas that eventually becoming state ideologies relied primarily on Chinese texts.

However, Hanja did not represent adequately many aspects of the Korean language, and the sheer volume of characters required significant time dedicated to memorization. Thus, only the ruling elite privileged enough to receive an education could learn to read and write Hanja leaving the vast majority of the population illiterate.

Sejong, seeking to enable the common Joseon person to read and write one’s language, started working on creating a new writing system more similar to an alphabet that would be easier to learn than the taxing memorization of each Hanja character, and he kept his efforts a secret foreseeing that the elites who saw Hanja as a symbol of their power and status would voice their opposition. While sources at the time report that the Joseon king personally created the characters, it is believed that he left the task to the Hall of Worthies, a royal advisory council of scholars that was transformed into a research institute by Sejong.

Whatever the case, by 1443 Sejong announced the completion of Hangŭl, and in October of 1446 Sejong promulgated the new writing system to the Joseon public. Originally he called his project Hunminjeongeum, which means “to teach the people proper sounds” as the name Hangŭl is a recent invention.

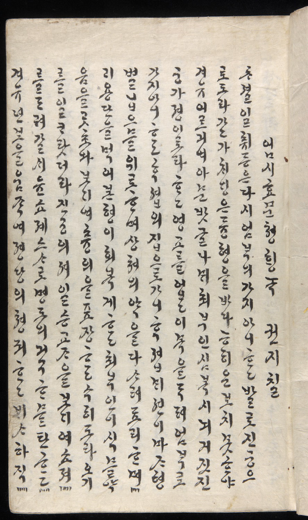

While the elites, who referred to Hanja as “true letters”, continued to resist the incorporation of Hangŭl, the new script was quickly adopted by the general populace, especially enabling women to read and right to the extent that the elites also called Hangŭl “women’s script”. Sejong and his successors, fulfilling their obligations as Confucian rulers, were able to convey its moral virtues to the common people directly translating texts previously written only in Hanja into Hangŭl. The Beinecke library has one such text, a 19th century copy of Ŏm Ssi hyomun ch'ŏnghaengnok focusing on the theme of filial piety, which also happens to be an excellent research resource on the history of Hangŭl. Hangŭl also found popularity as the writing system of choice for popular literature.

With the rise of Korean nationalism in response to Japanese imperialism, Hangŭl became the widely accepted writing system as hanja faded from common usage outside of academic circles. In light of this important aspect of Korean heritage, today the South Korean government considers October 9th a national holiday, Hangeul Day.