by Sam Yankee, Yale University ’25

Written for HIST 790: Ports, Cities, and Empires

Edited by Sophie Garcia, Oliver Giddings, Elijah Hurewitz-Ravitch, Baala Shakya, Ainsley Kroon, and Maya Mufson

The glassy water of the Hooghly River parted under the prow of a low craft rowed by lascars sweating under the hot May sun. A black-coated American, sweltering in his neck-cloth and waistcoat in the hundred-degree weather, stood in the stern sheets with a bundle of account books clutched under his arm. It was May 22, 1812, when Henry Lee, once a prosperous Boston merchant now fallen to bankruptcy, disembarked from the brig Reaper of Boston onto the quays of Calcutta. The scents of incense and spices, once familiar in his own warehouses, mingled with the odor of a city teeming with life, wafting through the rigging of Arab dhows, American brigs, and heavy British East Indiamen. Over the next four years, this city in the heart of British India would become Lee’s new home, where he would confront the web of social, business, and political challenges that lay before him, a man nearly 8,000 miles from his homeland in a world engulfed in war.

Lee remained in Calcutta from May 1812 to May 1816, serving as a commercial agent for a consortium of Boston-based merchants. While American merchants are not frequently associated with the history of British India — nor is India treated as integral to the history of the early American republic — American traders were vital to the rapidly unfolding system of global trade of that era. Following the ratification of the Treaty of Paris in 1784, enterprising merchants and their shipmasters flew the Stars and Stripes as far as the Bay of Bengal, the Spice Islands, and southern China. Throughout his years in Calcutta, Lee frequently wrote home to his wife, Mary, and to his investors and business associates, chief among them his brothers Francis and Thomas and his cousin Andrew Cabot. The letters reveal the intimacy of close kinship; Cabot had, before Lee’s reversal of fortunes, served as Lee’s own supercargo in Calcutta while Lee remained in Boston. Lee described Mary as his “prudent counsellor” and “sage advisor,” writing that he sought her advice in all that he did.1 The correspondence of Henry Lee, a Boston supercargo and commercial agent in Calcutta from 1812 to 1816, opens a window into the social and political life of American merchants in British India, where they relied heavily on a global information network while negotiating a role in the British imperial social and commercial order and coming to terms with American politics amidst the Napoleonic Wars.

While several historians have studied the economic history of the early nineteenth-century American India trade, few have considered its social and political implications holistically. Furthermore, while Lee’s correspondence has been cited in numerous works regarding his economic and commercial insights, little attention has been given to his political rhetoric and social commentary. This is not a surprise; the vast majority of Lee’s published correspondence, compiled in Kenneth Wiggins Porter’s two-volume Harvard Business School collection, is almost entirely commercial in nature.2 Where Porter gives analysis, he generally provides context for the reader in understanding the various persons, goods, and places mentioned in the letters. On the other hand, a much slimmer volume containing Lee’s personal correspondence with his wife, Mary, has been self-published by their descendant Frances Rollins Morse with little commentary beyond the recollection of childhood memories at the family homestead.3

Citations of the Lee correspondence—whether from the Porter or Morse compilations—have typically appeared in the context of economic history. Historian Amales Tripathi has written extensively on the structure of early nineteenth-century trade in Calcutta in his Trade and Finance in the Bengal Presidency, and Lee is cited several times throughout the work. His correspondence is used to elucidate tariffs, exchange rates, commodity prices, and the handling of banians, local Indian brokers employed by foreign merchants.4 Tripathi foregoes social considerations for a detailed account of the emergence of capitalism and the market system in Bengal. Likewise, Goberdhan Bhagat, in his Americans in India, 1784-1860, mentions Lee a few times as an example in discussions of Americans’ partnerships with banians.5

Another historian, James Fichter, has written extensively on the importance of American commerce in India, focusing on how the East Indies trade was critical to the birth of the corporation in the United States and in the global economy. Fichter gives an illuminating account of the diplomatic relations that shaped American trade with British India, as well as the general structure and development of that trade. Furthermore, Fichter discusses the decline of the East India Company’s shipping business and how the market participation of American traders opened the door for free trade across the globe. Ultimately, Fichter concludes that free trade in the British Empire and beyond was at least partially a consequence of American traders in the East Indies.6

Despite the dominant narrative of commerce in these works, the social aspects of Lee's correspondence have not been entirely ignored. In his discussion of the history of Americans in the Indian subcontinent from 1784-1838, Michael Verney frequently uses Lee as an example of a New England Indies merchant. Verney, unlike many others who have cited the same corpus of letters, considers the relationship between the Indies merchant and his banians and other Indians. Verney also examines the role of early American missionaries in Calcutta and other Indian ports, yet, while he gestures toward political context in his introduction, he offers little analysis of the social and political role of the East Indies merchant within the Anglo-Indian cultural space.7

Historian Mark Peterson, in his book, The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630–1865, posits that, for much of its history, Boston functioned as an autonomous city-state controlling a small landmass, yet exerting political and economic power worldwide. Peterson presents a thorough political history of Boston in the early nineteenth century, but he does not account for the politics of Bostonians abroad, who, using his framework, functioned as the trading outposts of the commercial city-state. Nevertheless, Peterson clearly conveys the vitriolic anti-Madison sentiments of Boston’s civic leaders during the war years.8 To contribute to this body of scholarship, a broader historical context of New England-Calcutta economic relations is required.

Throughout the United States’ early relations with Great Britain, a series of policies on both sides shaped trade engagement, but Calcutta’s position on the periphery of the empire consistently eased American access to the market. After the Treaty of Paris established peace and the sovereignty of the United States in 1784, the first major treaty between the United States and Great Britain was the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation of 1795, commonly referred to as the Jay Treaty, after principal negotiator John Jay. The Jay Treaty sought to resolve residual ambiguities from the settlement eleven years earlier. Article XIII of the Treaty authorized all American-owned vessels to trade freely with the British East Indies, subject to no higher duties than those paid by British vessels. However, American vessels were only authorized to carry goods from British East Indies ports directly to American ports.9 Furthermore, Article XXVI states that in the case of a war between the United States and Great Britain, merchants of the one state residing in the other “shall have the privilege of remaining and continuing their Trade so long as they behave peaceably and commit no offence against the Laws.”10 While a war might prevent American bottoms from carrying cargo, it would not prevent well-behaved American merchants from conducting trade in British bottoms.

In subsequent years, however, the “true and sincere friendship” urged by the Jay Treaty was complicated by waves of warfare between Britain and France, in which neutral American merchants profited by carrying goods to both sides. In an effort to limit aid reaching France, Britain issued Orders in Council in 1807 effectively prohibiting all vessels, neutral or otherwise, from calling at French ports, upon the enforcement of the Royal Navy.11 Any American vessel carrying goods to a French port could now be seized by British authorities. In response to anger at the British seizure of American vessels and impressment of seamen, the United States Congress passed the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited all American maritime exports.12 This proved unsuccessful at strengthening the nation’s international political position and was sufficiently damaging to the American economy that it was repealed and succeeded by the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, which ultimately closed American ports to trade with Britain and France, whether carried in British, French, or even American bottoms.13 This new act, however, did not prevent American merchants from carrying goods between foreign ports, and trade continued.

The Non-Intercourse Act’s effects caused nearly as much of a stir among British East Indies merchants as it did among Americans. Indeed, as much of the world’s silver specie at the time came from sources in Spanish America, and as American merchants were the primary traders in Spanish ports, the American trade was critical to the supply of specie in India, and thus in British markets. Even Sir Francis Baring, the great financier, wrote to the East India Company’s Court of Directors, lauding the important role of American traders in the prosperity of India. This sentiment was not lost in Calcutta. In a letter to his brother Thomas in 1812, Lee wrote, “Most of the funds this year having come in bills instead of specie, I find [the English Calcutta merchants] view the loss of our trade on that account as a great evil.”14 Without American-shipped specie flowing into the Calcutta money markets, free-trading merchants and Company officials had much greater difficulty securing credit to finance their purchases. Nevertheless, the availability of specie was only one factor in deteriorating trade conditions.

Although the Orders in Council were repealed in June 1812, the United States Congress’s declaration of war complicated efforts at trade with the Indies, leading to British detention of American vessels in most ports. This, however, did not necessarily result in the arrest of American merchants in British ports. As historian Holden Furber has written, the Bengal government effectively refused instructions from East India Company headquarters to restrict the trade of American merchants and vessels.15 Lee, who had eagerly awaited the repeal of the Orders in Council since his arrival in Calcutta, was shocked and dismayed to hear of the declaration of war. Regardless of the Bengal presidency’s lax administration of the metropol’s policies, war between the two nations would inevitably lead to the interdiction of shipping and a spike in insurance rates, among other challenges. Indeed, Lee’s discussion of the Madison administration’s political decisions differs starkly from his perspective on the actions of Company officials.

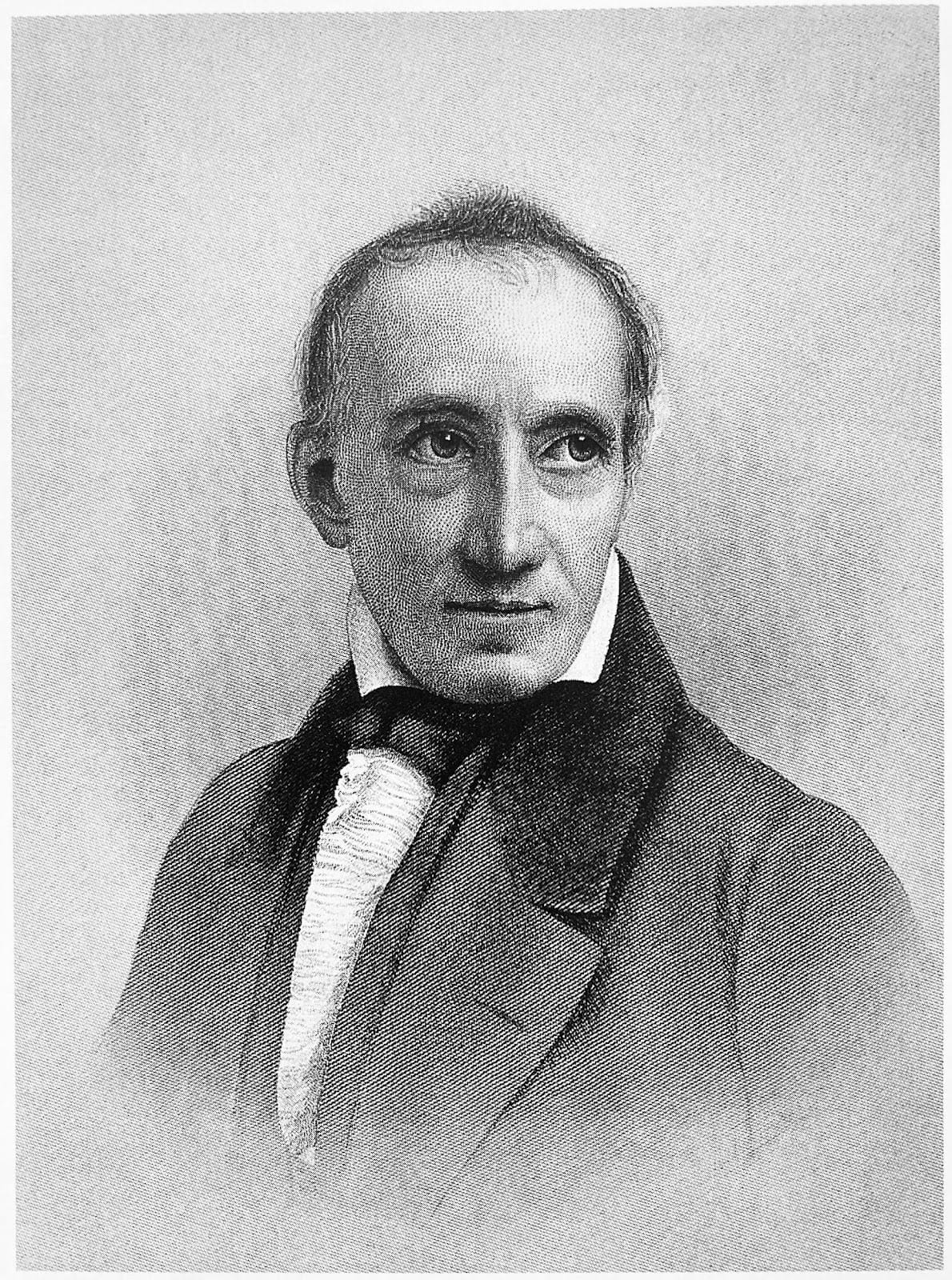

Figure 2: Henry Lee (1782-1867), c. 1860, after a painting by Spiridione Gambardella (c. 1815-1886), c. 1840. Engraving, 23 x 16 cm; Courtesy of Henry Lee. Printed in Bean, Yankee India.

Lee’s disaffection with the Madison regime and his good relations with Anglo-Indian authorities suggest a shifting allegiance to a broader Anglosphere of trade and culture. After news of the outbreak of war reached Calcutta in February 1813, Lee’s correspondence reveals that he felt more in common with British merchants in Calcutta than with the Democratic-Republican politicians in Washington, most of whom hailed from Virginia and the mid-Atlantic states. Shortly after the news of war arrived, Lee wrote to his wife that “if the war between the two countries continues I am of course a prisoner of war; you may perhaps attach some unpleasant idea to this, but my situation will not be in any respect different from what it is now, only I shall not be permitted to depart without permission from government who no doubt will give me parole when I shall apply for it.” This underscores Furber’s assertion that the Bengal administration had little interest in London’s policies. Furthermore, Lee continued to write in his letter that “the people in this place have always been particularly friendly towards Americans and regret exceedingly the war.”16 Clearly, the Boston merchant found goodwill with his British counterparts.

Indeed, reinforcing Lee’s august view of Calcutta’s administrators was the fact that he and they could find a common enemy in the Democratic-Republicans. Sharing this sentiment with Mary, he wrote, “The people here consider the war as having been commenced by the [Madison] Government and their partisans the rabble, contrary to the wishes of our best citizens and lamented most sincerely– there is no animosity towards us whatsoever.”17 In this line, we not only see a condemnation of Madison’s supporters as mere “rabble,” but a belief that the “best citizens” of New England and the British Empire were of one mind.

Even Lee’s rhetoric describing Madison contrasts sharply with his description of British leaders, suggesting disdain for the one and modest admiration for the other. Upon the arrival in Calcutta of Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings, then Earl of Moira and later Marquess of Hastings, Lee and his house-mate Captain Chardon went to the waterfront early in the morning to see the new governor-general and his wife land in state. Because of the small crowd due to the early hour, Lee was able to get a good look. “Lord Moira was dressed in his military uniform and decorated with his star and garter. He is a well-made, good-looking man of about sixty, has a countenance full of benevolence, and is rather intelligent.”18 A few months earlier, meanwhile, Lee lamented to his wife that but for “the wicked and stupid policy of our abandoned rulers we should still have been at peace and prosperous.”19 The benevolent and “rather intelligent” Lord Moira, an aristocrat ruling by virtue of appointment, was far more desirable to Lee than the “abandoned rulers” of Washington, despite the fact that they, unlike Moira, held their mandate by public election.

Lee’s excoriation of the Madison administration does not stop there, however, nor does his praise of Moira; he suggests that the well-born Moira was more capable of governing than the “rabble” in Washington. Writing home about the escalation of conflicts, Lee suggested that “our people of both parties have been duped by the Government faction into a belief that Madison was contending for the rights of the nation. I never supposed our corrupt and traitorous rulers were sincere in negotiating, but I thought the mass of the nation, when once the most obnoxious pretense for war was done away, would be for peace.”20 In Lee’s mind, Madison and his allies were not merely reckless, but actively duplicitous as well as “corrupt and traitorous.” Conversely, Lee described Moira as “one of the most virtuous and popular noblemen in England,” who would “support the dignity of Government in a way to command the respect of the natives.”21 Lee’s admiration is clear; whereas Madison and his Democratic-Republicans were traitorous cheats, the administration of the East India Company was benevolent and deserving of respect.

Lee’s appreciation of English upper-class culture was paralleled at home, where the well-to-do of Massachusetts surrounded themselves with British goods and ideas. With access to goods from around the world, Salem housewives sought English cutlery and chinaware to grace their tables.22 The 1818 catalog of the Salem Athenaeum, a subscription library established in 1811, boasts more than twice as many books published in London, Oxford, Bath, Dublin, Edinburg, Aberdeen, Glasgow, and Westminster than in Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Richmond, Hartford, New Haven, Salem, and Albany.23 Immersed in the writings of the great British political philosophers, the men of Salem and Boston could hardly be called provincial. Not only did New England’s political sentiments lean toward amiability with Britain, but thousands of dollars were spent to keep up with the latest British trends, whether academic or aesthetic.

As Federalist sentiments came to a boil at home during the Hartford Convention of 1814, Lee likewise expressed a greater loyalty to his mercantile class and New England identity than to the United States. On February 14, 1813, he wrote to his wife that he had heard “to my great sorrow of the war continued,” and that “our privateers were active but I was glad to learn that most of them were taken.” Not only did Lee applaud the defeat of American privateers at sea—a surprising comment when many were owned by his fellow Boston merchants—but he wished failure upon American military efforts on land, writing that “our troops had commenced an attack on Canada where they met a repulse as might have been expected: it is best we should not succeed in any of the war measures: peace will sooner follow.”24 This comment moves beyond the realm of political disaffection into what might well be defined as treason. Lee even went so far as to advocate for secession from the Union, writing to Mary in late February of 1813:

If we were united in New England, and New York would join us heartily, the western states might have the war to themselves. We must one day or another separate and since things have gone so far, the sooner it takes place the better. The northern section would soon have the ascendancy and control over the others, and thus govern instead of being governed by a people half civilised.25

In these lines, Lee wholeheartedly declared that the breakdown of the United States was inevitable. Lee’s “best citizens” could then regain their “ascendancy and control over the others” and proclaim a new, more closely federated state not dissimilar to the governance of the Anglo-Indian community from Calcutta. The Governor-General of India, accountable to the Court of Directors, itself composed of successful commercial men, could hardly have been far from Lee’s mind when he made this remark. Rather than Madison’s distasteful attraction to the will of the uneducated populace, a well-informed man like Moira could be selected from among the leading figures of the Northeast by an assembly of his peers.

Lee did not hesitate to compare Madison with Napoleon, declaring his administration despotic for disregarding the will of the Northern mercantile class. In March 1813 he wrote, “in fact it is very apparent [Madison and his allies] are as much in [Napoleon’s] interest as his own Senate. . . . There never was a set of men in power in any country, more contemptible as to talents or more base as to their conduct and views than Madison and his faction— detested by all good men in their own country and despised by all the rest of the world.”26 Napoleon, while wildly popular in France, was a despot to Lee because he was not checked by a ruling elite; Madison, elected by the settlers, craftsmen, and yeomen farmers of the southern and western states, likewise seemed unchecked. Regardless of its aims, the Madison administration did aid Napoleon by declaring war on Britain, thus demanding some of that nation’s military resources be diverted to North America.

While Lee proposed the separation of the American states, he nevertheless seems to have remained committed to its institutions, lamenting the weakness of the Constitution. In the same letter in which he declared secession to be inevitable, he wrote, “I look upon the government as nearly dissolved by the war. The Constitution was too miserably weak to serve in peace when everything went on prosperously— it cannot be expected that the faction now and power will any longer regard it. . . .”27 This shifts the question from one of dissolution to one of succession to the union of 1789. Rather than ideologically forsaking the federal organs of state, Lee expresses regret over their inefficacy at maintaining the values espoused by the Founding Fathers.

Lee’s vision parallels the situation in Upper Canada at the time, where the “Family Compact” group of prominent families had begun to assert oligarchical control over the province from the early nineteenth century. Indeed, the similarities do not end there. Upper Canada, settled largely by loyalist emigrants fleeing the American states during and after independence, could also be seen as a breakaway state like the New England-New York union proposed by Lee.28 Far from the rabble rule that horrified Lee in the United States, Upper Canada was governed by a locally-elected assembly, appointed executive and legislative councils with members drawn from the provincial ruling class, and an appointed lieutenant governor. This must have been an appealing model for a man who wrote frequently about his desire for rule by the “best citizens.” Upper Canada’s oligarchic self-governance within the British Empire would have been viewed favorably by the elite of New England, for whom such a regime would preserve trading rights within the British sphere, while enabling fiscal control by the elites themselves through an assembly.

Lee’s internationalism, while rooted in the commercial and Federalist politics of his peers, pushed far beyond what was commonly supported at home. Phillips has written that, although the war was politically unpopular in Boston and Salem, the citizens of both these cities wholeheartedly contributed to the war effort when it was close at hand. Salem even raised a number of militia companies to defend its coastline, and scores of Salem and Boston men manned the guns of the U.S. Navy’s frigates.29 Lee, removed from the bonds and support of his native community, was more moved by his international worldview and commercial relations than by nationalism or patriotism.

Despite Lee’s affinity for the British Empire’s trading and political benefits and refined upper classes, he remained a conservative New Englander, and reviled the lower classes of Anglo-Indian Calcutta for their vulgarity and ignorance nearly as much as he despised the nouveaux-riches of the United States. He wrote to Mary in April 1813 on the stratified nature of Calcutta’s Western community:

There are two classes of people that make up the English societies– the one composed of Company’s servants, as they are called, viz. persons in service of the India Company– military officers and a few merchants. These are the gentry of the place and have among them many respectable persons— live in great style and hold themselves all together above the common citizens. The other class is made up of merchants, mechanics, shopkeepers, artists, shipmasters, and adventurers of all sorts, who came out from England to seek what they seldom find— their fortunes. For the most part they are a low-bred and worthless set— their society is had on easy terms— you may be sure I have no inclination, and if I had, would not indulge it, to partake of it.30

The irony of this condemnation is apparent; Lee, who was a merchant himself (and rooming with a shipmaster), sought his fortune in Calcutta much like the “low-bred and worthless” commonplace Englishmen. Despite this, he viewed himself as more closely aligned with the Company servants and other “gentry of the place.” Perhaps Lee was drawn to the increasingly international identity of the British ruling class– men such as the Anglo-Irish Lord Moira could govern places as far as Bengal or Cape Town, flying not local flags but the Union Jack and the Company ensign.

Lee’s haughty attitude toward the lower classes of Britons in Calcutta matches his disdain for those whom he perceived as the newly-elevated ruling class of the southern and western states. In February 1813 he wrote, “The rich are usually cowards, . . . for the most part without any other principle than avarice– without education suddenly rais’d from the most humble condition to that importance which money confers.”31 Lee, who had studied at Phillips Academy, Andover, and whose two brothers had attended Harvard, hailed from a family that valued education and possessed the means to support it.32 Economic historian Edwin West has written that the literacy rate in the southern American states in 1800 was around fifty-five percent, whereas that figure sat at ninety-eight percent in Massachusetts.33 Not only was literacy effectively universal in Massachusetts, but even the poorest children in towns such as Salem and Boston had access to a free education in Latin, French, English and arithmetic.34 The same could not be said for the working classes of Britain, nor for the voters who had put Madison in the White House. Because of this educational divide, it is clear why Lee felt himself and his Yankee peers to be a unique class positioned between British gentry and the common mercantile and working classes of the Anglo-American world.

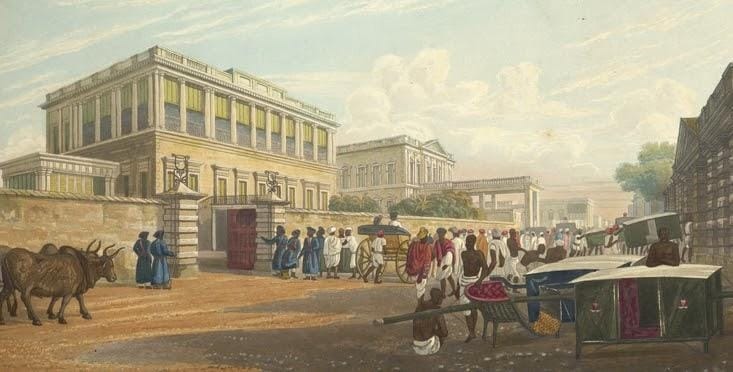

One member of the upper set of Anglo-Indian society with whom Lee did have social and business relations was John Palmer of the prominent Calcutta agency house Palmer & Company. Lee, who seldom went out, wrote to his wife in April 1813 that he had “dined twice at a house where business introduced [him].”35 This was likely the house of Palmer, to whom Lee wrote upon his return to the United States, thanking him for “the friendly manner you always treated me during my residence in India… and at the same time my sincere thanks for the many instances of your Kindness, and friendship, which are still fresh in my recollection. . . .”36 Palmer’s agency house was by 1813 the largest in Calcutta and enjoyed special privileges under Moira’s administration, allowing him to lend money to Indian princes. Palmer’s primary business activity, however, was to invest the money of Company officials, acting as a private bank and brokerage.37 Palmer, whose house is depicted in Figure 3, clearly amassed a great deal of wealth. He acted as a trusted advisor to many Company writers and to men like Lee, whose personal correspondence he handled while Lee was away for a time in late 1813.38 It is apparent that, with the proper introductions, the liberally educated Lee was able to transcend the class divide of British imperial society.

Figure 3: James Baillie Fraser (1783-1856), View of the Loll Bazaar opposite the house of John Palmer, Esq., ca. 1825-1826. Collection of the British Library.

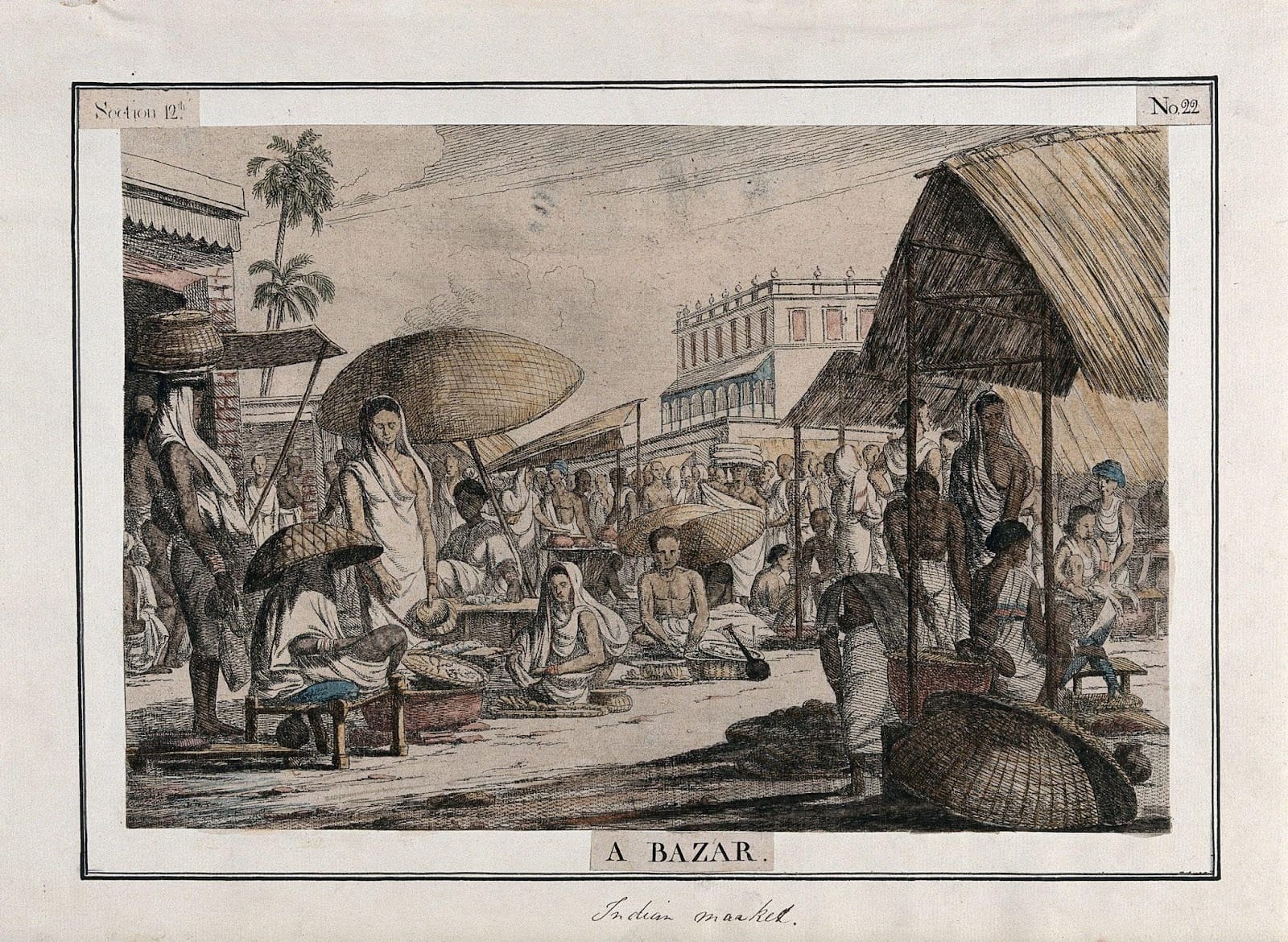

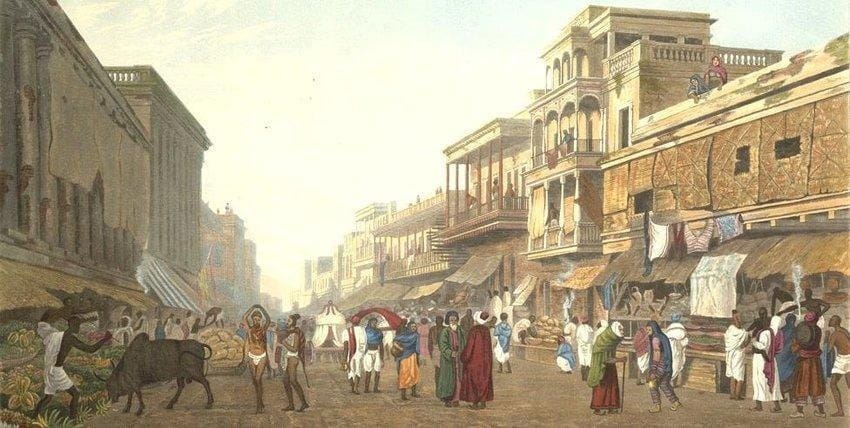

Figure 4: Balthazar Solvyns (1760-1824), Market Scene, Calcutta, West Bengal, 1799. Etching with watercolor. Wellcome Collection. Image via JSTOR.

Lee’s appreciation of Indian society and world events suggests a greater nuance and openness than his rhetoric about the leading figures of the United States and Britain, belying the influence of Calcutta’s role as a bazaar of information and ideas. Through Lee’s correspondence with his wife and business partners, we see the development of a grudging respect for local Indian society and its customs. At the forefront of this is Lee’s interaction with his banians. As historian Michael Aldous has written, the banians were not merely members of the baniya caste, whose members were primarily engaged in commerce and finance, but were a specific type of professional who acted as brokers, translators, financiers, and even junior partners for British and American merchants doing business in India from the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century.39 Banians connected merchants to local markets, introducing them to urban bazaars and other commodity markets, such as the bazaar depicted in Figure 4. Where a Western merchant would be entirely adrift, a banian served as his guide in commerce and local customs. Banians also provided capital, local business insight, and handled the hiring of local labor. Indeed, other than his three American cohabitants, Lee’s only regular personal interactions in Calcutta were with his two banians, Tillock and Ramdon.

In a letter to Andrew Cabot on October 5, 1812, Lee attested to Tillock and Ramdon’s business acumen and urged his partner to engage their services in the future. Lee’s praise could hardly be more positive:

I have been perfectly well satisfied with my Banians. . . I think them much more capable in their business than any of the others and they have every motive that can operate upon men desirous of establishing a reputation and acquiring wealth; . . . In meantime I am exceedingly desirous you should do all you can to recommend them and that in any future voyages you undertake to this place give your supercargo orders to employ them. . . .40

Underscoring his praise of these two men, Lee wrote that they had hired the best workers in the city, and that Tillock “manages with great address the natives who come to the godowns,” and that, in sum, the pair were “. . . deserving of your confidence in a much greater degree than you would venture to place in any native of this country.”41 Not only were Ramdon and Tillock reliable and commendable partners, but they kept Lee’s financial accounts, hired his workers, and represented him in interactions with the “natives who come to the godowns.” The banians even cosigned customs bonds alongside the Lee and the Reaper’s master.42

However, while the two banians were indispensable to Lee’s commercial activity, he had little to say in support of their social graces. Lee complained of their banality, writing to his wife in September of 1812 that the banians “never had, nor ever will have a thought except on business. Were the natives as well informed as they are civil and well-bred, one would receive great pleasure from their society, but their opinions are so confined, that I can truly say I never derived half an hour's gratification from any one I have been acquainted with. Nothing can be more uninteresting than their characters.”43 Despite Lee’s high praise of Tillock and Ramdon’s good manners, he disparaged their social qualities as immeasurably dull. This, from a man who in a later letter wrote of how he had in his free time “gone through the Bible a second time and Paley's Sermons two or three times,” is a very low evaluation indeed.44 While the banians were Lee’s close partners in the business world, it is clear that they were not his social peers.

Further compounding this frustration was Lee’s total exasperation with the complex religious customs of his domestic servants. He wrote to Mary in May 1813 that “they plague me by their religious scruples— they will not touch the warm water or carry a light before the palanquin. . . . The business of a house from their religious customs is subdivided into many branches, for each of which there must be a servant; this is a great expense and still greater inconvenience. . . . The same servants are required for me as for half a dozen.”45 For a man used to the thrift of New England, this was simply maddening; whereas at home, after his financial ruin a few years earlier, an austere staff of perhaps a maid or a cook would have been maintained, Lee’s Calcutta household apparently included palanquin-bearers, cooks, stewards, and others whose posts were dictated by their castes and social standing.

Nevertheless, Lee, unlike many later Westerners, did his best to understand the customs of the city and its people, even when he found these customs immensely frustrating. He wrote to Mary in 1813, “I read most of my time . . . and study the language of the country a few hours a day.”46 It is unclear whether this language was Bengali or Persian, as Persian had until that point been the primary literary and administrative language of the region, yet Bengali was spoken by the masses and was available in print from 1800.47 In a later letter home, Lee expressed delight at having found a “translation and digest of the Hindu laws.”48 Despite his frustrations with local customs, Lee's immersion in the language and laws of the region underscored his genuine attempt to understand Calcutta's culture. This appreciation extended to his criticism of other Westerners in the area.

Another dimension of Lee’s appreciation for local culture is revealed in a letter home about the activities in Calcutta of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, in which he decried the missionaries’ quest for conversion as misguided and unnecessary. The Board was established in 1810 as the first American missionary society dedicated to overseas proselytization. Their first destination was Calcutta, and to that city they sent the New England missionaries Gordon Hall, Samuel Nott, Adoniram Judson, Samuel Newell, James Richards, and Luther Rice.49 Despite Lee’s own Bible-reading fervor, he had little to say in support of these men. He wrote to Mary several months after their 1812 arrival that “as yet few or no converts have been made, perhaps not one respectable native, and it appears to me beyond the reach of human means to change their notions: certainly while [the missionaries] remain as at present in the grossest ignorance of everything but the particular profession they are engaged in. . . . All of them seem to be ignorant of the world, and extremely ill-informed of the country and the inhabitants which they came to convert.”50 While Lee may not have been pleased with the practices of all of his local contacts, he reviled the attempts by these missionaries to convert Hindus to Christianity and disparaged the missionaries as fools for having no knowledge of the part of the world in which they sought to work.

Lee’s commentary on business arrangements, domestic staffing challenges, and foreign missionary activity reveals his nuanced relationship with local Indian society and its customs, especially with regard to his interactions with the banians Tillock and Ramdon. Lee’s condemnation of their social graces did not hinder his praise of their business acumen, nor did his frustration with cultural differences prevent him from seeking a deeper understanding of Calcutta’s language and culture. Lee’s discontent with the proselytization of New England ministers underscores his appreciation for local customs. In contrast, Bhagat has written that few Americans wrote home about social and political conditions in India, and those that did were generally displeased with what they experienced of the Indian populace.51 Lee, by seeking to educate himself on local cultural practices and language, seems to be an outlier.

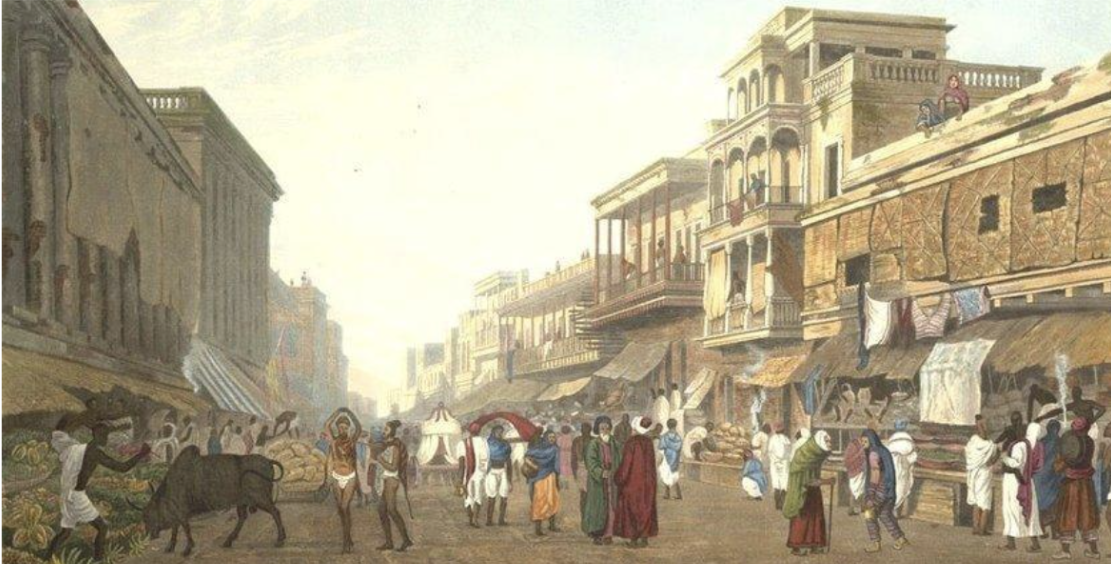

Figure 5: James Baillie Fraser, A View in the Lal Bazaar leading to the Chitpore Road, on the north side of Dalhousie Square in Calcutta, 1826. Aquatint, 11 x 16 in. Printed in Fraser's Views in Calcutta, Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Much as Calcutta’s bazaars connected merchants with goods from around the world, the city was a global hub of information, further bolstering Lee’s international perspective. Of the thirty-two letters Lee wrote from Calcutta that are published in the Porter collection, eighty percent were addressed to correspondents in Boston or New York, ten percent to correspondents in London, and ten percent to correspondents in India or China.52 However, Lee and his American and British competitors were not the only international trading network active in Calcutta. In Lee’s first letter to his brother Thomas upon arriving in Calcutta, he wrote,

I have made particular inquiries about Mocha Coffee of Merchants of Muscat, Mocha, & Bussarah [Basra]. . . . While the Country is distracted with Civil wars between the Whabees [Wahabis] & other sects of the Mahometans, the cultivation is nearly suspended. . . . Some of the Persian Merchants inform me Saltpetre can be had at Muscat, but others say not, I imagine the latter to be correct, however I have written over. . . . The Arabs now carry on a great trade here. 25 ships look’d for indigo is an article they take largely of, they send it over land to Turkey and even into Greece, Italy, &c. They bring to this place drugs, fruits, horses, specie &c.53

In this extract, Lee describes his correspondence with Persian and Arab merchants in Mocha, on the Red Sea, Muscat, on the Gulf of Oman, and Basra, a riverine city near the head of the Persian Gulf. These merchants, in turn, carried an overland trade through Persia, the Levant, and Turkey to the eastern Mediterranean. In addition to the availability and prices of indigo, coffee, and other commodities, they discuss the wars in which the Wahabis, the conservative Islamic sect that today rules Saudi Arabia, battled Bedouin tribes and the ultimately victorious armies of Ottoman Egypt.54

From Europe, news streamed in about developments in the wars against Napoleon. In early March 1813 Lee wrote, “I have rec’d much gratification from learning the success of the English in Spain— they are doing wonders there— and within a few days we have news from Russia of a terrible bloody battle fought near Moscow . . . the situation of Napoleon will be critical indeed this winter. . . . His defeat would change the view of our cowardly government, who have hitherto been operated upon by his threats. . . .”55 Here Lee, in Calcutta, writes a letter home to Boston via his agent in London, discussing the effect of the outcome of battles fought in Spain and Russia on politics in Washington. Lee’s news, likely coming in letters and newspapers carried by British vessels, was shared throughout the merchant community. Events around the globe shaped market conditions, reflecting the international nature of Calcutta’s bazaar of information.

In a letter home in April 1813, Lee described the various ways in which news arrived in Calcutta. While many letters arrived by ships rounding the Cape of Good Hope from London and other ports, other news came via land. Discussing how he and his colleagues had been following the war in Russia, Lee wrote, “We get our intelligence over land, principally from Mr. Liston, the English Ambassador in Turkey. It comes through Persia; thence to Bombay via the Persian Gulf: from Bombay, which is in the English Dominions, it comes by land to Calcutta.56 By sea, vessels carrying news braved the risks of capture by French and American privateers, as well as natural disasters inherent to any long voyage. On the route from Turkey, however, a dispatch carrier faced bandits on the Ottoman frontier, warring Arab tribes, pirates in the Persian Gulf, and countless tropical diseases while crossing India.

For commercial and personal correspondence, London was a key connection point. Throughout his time in Calcutta, Lee corresponded with Samuel Williams, of the London trading firm Wells and Williams. Williams functioned as the Cabots’ and Lees’ primary banker in London, providing them with letters of credit.57 Williams also handled Lee’s homebound correspondence and transshipments of goods. Most of the cargoes leaving Calcutta were in Portuguese bottoms, bound for Brazil, or British bottoms, bound for London. Any of Lee’s letters or cargo shipments that arrived in New England would have landed aboard British or American blockade runners. In a letter of July 1814 discussing the fall of Napoleon, Lee wrote to his brother Francis that he had been receiving regular political updates from Williams in London throughout the year.58 In May 1815, upon hearing news of the Treaty of Ghent bringing peace between Britain and the United States, Lee sent off another letter to Francis, sharing with him the impact of the news of peace on commodity prices in Canton, the Malabar Coast, Bengal, and the Persian Gulf. He also wrote that he would instruct Williams to begin directing his cargoes arriving in London to be reshipped to the United States.59 For the previous four years, despite tense hostilities between the United States and Britain, Lee had participated fully in the British imperial market, shipping goods in British vessels from British Calcutta to London, using British bankers and British agents. Now, the war was over.

With the arrival of peace between the great powers of the world, the economic and political order of the previous twenty years dissolved. Global détente, combined with the end of the East India Company’s monopoly on British shipping to India, heralded an age of international commerce in which vessels and merchants of all nations could, to some extent, participate. No longer did neutral Americans have a special role in the carrying trade between British and French ports, nor, with the end of the Company’s monopoly, were they the only shippers permitted to undercut bloated Company freight rates. In August 1815, Lee reported the arrival of the first American vessels in Calcutta since the outbreak of the war.60 In May 1816, he set sail for home.61

Upon Lee’s arrival home in the United States after a passage of only 120 days, he was a changed man in an even more changed country. Having set off to Calcutta with only $2,000 to his name, he returned moderately wealthy, as he wrote to his friend Palmer in Calcutta, “sufficiently so with my moderate expectations to enable me to pass the remainder of my life with my family. . . .”62 Lee had returned from the brink of bankruptcy to financial independence, able to renew his lifestyle as a sedentary merchant, living comfortably with his family at home. Meanwhile, the Federalists of New England, once ardently opposed to Madison’s national government, had begun to crumble into obscurity after the United States’s claimed victory. Without a disastrous war to oppose, they were often seen as unpatriotic. Lee, for his part, no longer faced embargoes on trade between the United States and Britain, leaving his concept of a greater Anglo-American commercial realm both challenged and realized; peace had brought both the permanent return of transatlantic commerce and a more durable American nationalism.

Through his time in Calcutta during the War of 1812, Henry Lee developed a sense of internationalism and desire for an Anglo-American trading and political sphere, driven by the global bazaar of information and cultures in which he found himself. From an era of flourishing worldwide trade, Lee’s correspondence opens a window into the oft-overlooked political and social ideology of Americans overseas. Indeed, even in his later life, Lee remained deeply invested in the India trade, unlike his peers who invested in the early industrial boom of manufacturing and supported an American system of tariffs. In a letter to the British colonial secretary, William Huskisson, Lee wrote that it was surprising to find the United States, long a free-trading nation, adopting tariffs, “when the only nation to whom we ought to look for instruction and example, is abandoning such a policy, after having experienced its evils; . . . I hope the day is not far distant when most of the civilized nations of the world will see . . . how much is to be gained by mutually acting on the just & liberal principles [of free trade].”63 Ever the East Indies merchant, Lee remained committed to global commerce and the principles of the British Empire long after they fell out of favor among his Yankee peers. Calcutta had left its mark.

Endnotes

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, January 12, 1813, in Frances Rollins Morse, ed. Henry and Mary Lee, Letters and Journals (Boston: [Privately published], 1926): 121. All letters from Henry Lee to Mary Lee hereon were posted from Calcutta to Boston, unless otherwise noted.

- Kenneth Wiggins Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees: Two Generations of Massachusetts Merchants, 1764-1844 (New York: Russell and Russell, 1969).

- Morse, Henry and Mary Lee.

- Amales Tripathi, Trade and Finance in the Bengal Presidency, 1793-1833 (Bombay: Orient Longmans, 1956): 139, 143, 145, 148.

- Goberdhan Baghat, Americans in India, 1784-1860 (New York: New York University Press, 1970): 48, 63, 71.

- James R. Fichter, So Great a Proffit: How the East Indies Trade Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010): 278-288.

- Michael A. Verney, “An Eye for Prices, an Eye for Souls: Americans in the Indian Subcontinent, 1784–1838,” Journal of the Early Republic 33, no. 3 (2013): 397–431.

- Mark Peterson, The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019): 382-443.

- “Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation,” signed at London November 19, 1794. The Avalon Project. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/jay.asp#art13. Article XIII.

- “Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation,” Article XXVI.

- Order in Council regarding trade with France, November 11, 1807. The Acts, Orders in Council, &c. of Great Britain [on Trade], 1793- 1812. https://www.napoleon-series.org/research/government/british/decrees/c_brit decrees24.html.

- Embargo Act of 1807, 2 Stat. 451 (1807).

- Nonintercourse Act of 1809, 2 Stat. 528 (1809).

- Henry Lee to Thomas Lee, Boston. Calcutta, August 12, 1812, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1035.

- Holden Furber, “The Beginnings of American Trade with India, 1784-1812,” The New England Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1938): 263-265. https://doi.org/10.2307/360708.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 10, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 127.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 18, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 131.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, October 11, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 161-162.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 14, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 129.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, January 14, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 123-124.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, October 11, 1813, 161-162.

- Phillips, Salem and the Indies, 345.

- A Catalogue of the Books Belonging to the Salem Athenæum with the Bylaws and Regulations (Salem: Salem Athenæum [printed by Thomas C. Cushing & Co.], 1811).

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 14, 1813, 128-129.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 22, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 132-133

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, March 5, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 136.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 22, 1813, 132-133.

- W. Stewart Wallace, The Family Compact: A Chronicle of the Rebellion in Upper Canada (Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Co., 1922): 1-33.

- Phillips, Salem and the Indies, 409-422.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, April 14, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 145-146.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 14, 1813, 128-130.

- Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 8.

- Edwin G. West, “The Spread of Education before Compulsion: Britain and America in the Nineteenth Century,” The Freeman (Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.) 46, no. 7 (July 1, 1996): 488.

- Phillips, Salem and the Indies, 353.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, April 14, 1813, 145-146.

- Henry Lee to John Palmer, Esq. of Calcutta, via ship Ramduloll Day. New York, September 12, 1816, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1189-1190.

- Tripathi, Trade and Finance, 183-186.

- Tony Webster, “An Early Global Business in a Colonial Context: The Strategies, Management, and Failure of John Palmer and Company of Calcutta, 1780-1830,” Enterprise & Society 6, no. 1 (March 2005): 131.

- Michael Aldous, “Partners, Servants, or Entrepreneurs? Banians in the Nineteenth-Century Bengal Economy,” Business History Review 94, no. 4 (2020): 676. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680520000689.

- Henry Lee to Andrew Cabot, Boston. Calcutta, October 5, 1812, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1061-1062.

- Henry Lee to Andrew Cabot, Boston. Calcutta, October 5, 1812, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1061-1062.

- Henry Lee to Andrew Cabot, Boston. Calcutta, May 20, 1812, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1013.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, September 15, 1812, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 117.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, January 26, 1814, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 163.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, May 3, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 151.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 10, 1813, 126.

- T. W. Clark, “The Languages of Calcutta, 1760-1840,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 18, no. 3 (1956): 461. http://www.jstor.org/stable/610111.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, February 13, 1816, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 166.

- Verney, “An Eye for Prices,” 420.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, April 27, 1813, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 150.

- Bhagat, Americans in India, 120-125.

- Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1563-1565.

- Henry Lee to Thomas Lee, August 12, 1812, 1035.

- James Wynbrandt, “The First Saudi State (1745–1818),” in A Brief History of Saudi Arabia, by James Wynbrandt, 3rd ed. (New York: Facts on File, 2021). https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6NDkwNDAzOA==?aid=98527.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, March 5, 1813, 136.

- Henry Lee to Mary Lee, April 14, 1813, 143.

- Andrew Cabot to Henry Lee, Brig Reaper. Boston, August 19, 1811, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 974.

- Henry Lee to Francis Lee, Boston. Calcutta, July 30, 1814, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1103.

- Henry Lee to Francis Lee, Boston. Calcutta, May 8-27, 1814, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1127-1141.

- Henry Lee to Francis Lee, Boston, via ship Isle de France. Calcutta, August 7, 1815, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1144-1151.

- Henry Lee to Goluck Chunder Day and Ramdon Bonarjia, Calcutta. Ship Portsea off Hooghly Delta, May 14, 1816, in Porter, The Jacksons and the Lees, 1170.

- Lee to Palmer, September 12, 1816.

- Henry Lee to William Huskisson, Secretary of State for the Colonies, London. Boston, December 21, 1827, in Morse, Henry and Mary Lee, 249-251.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Embargo Act of 1807, 2 Stat. 451 (1807).

Morse, Frances Rollins, ed. Henry and Mary Lee: Letters and Journals. Boston: Thomas Todd Co. Printers, 1926. Contains a series of letters written from Lee home to his wife from Calcutta, from roughly 1811 to 1816.

Nonintercourse Act of 1809, 2 Stat. 528 (1809).

Porter, Kenneth Wiggins, ed. The Jacksons and the Lees: Two Generations of Massachusetts Merchants, 1764-1844. New York: Russell and Russell, 1969. Contains a series of business letters written by Henry Lee, 1804-1844.

“Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation.” Great Britain and the United States. Signed at London November 19, 1794. The Avalon Project. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/jay.asp#art13.

Secondary Sources:

Aldous, Michael. “Partners, Servants, or Entrepreneurs? Banians in the Nineteenth-Century Bengal Economy.” Business History Review 94, no. 4 (2020): 675–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680520000689.

Bean, Susan S. Yankee India: American Commercial and Cultural Encounters with India in the Age of Sail, 1784-1860. Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Museum, 2001.

Bhagat, Goberdhan. Americans in India, 1784-1860. New York: New York University Press, 1970.

Clark, T. W. “The Languages of Calcutta, 1760-1840.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 18, no. 3 (1956): 453–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/610111.

Fichter, James R. So great a Proffit: How the East Indies trade transformed Anglo-American capitalism. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Furber, Holden. “The Beginnings of American Trade with India, 1784-1812.” The New England Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1938): 235–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/360708.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783-1860. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1921.

Peterson, Mark. The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Phillips, James Duncan. Salem and the Indies: the Story of the Great Commercial Era of the City. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1947.

Roy, Tirthankar. “Trading Firms in Colonial India.” Business History Review 88, no. 1 (2014): 9–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680513001402.

Tripathi, Amales. Trade and finance in the Bengal Presidency, 1793-1833. Bombay: Orient Longmans, 1956.

Verney, Michael A. “An Eye for Prices, an Eye for Souls: Americans in the Indian Subcontinent, 1784–1838.” Journal of the Early Republic 33, no. 3 (2013): 397–431. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24487047.

Webster, Tony. "An Early Global Business in a Colonial Context: The Strategies, Management, and Failure of John Palmer and Company of Calcutta, 1780-1830." Enterprise & Society 6, no. 1 (03, 2005): 98-133. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/early-global-business-colonial-context-strategies/docview/218623352/se-2.

West, Edwin G. “The Spread of Education before Compulsion: Britain and America in the Nineteenth Century.” The Freeman (Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.) 46, no. 7 (July 1, 1996).

Wynbrandt, James. A Brief History of Saudi Arabia, 3rd ed. New York: Facts On File, 2021.

Images:

Fraser, James Baillie (1783-1856). A View in the Lal Bazaar leading to the Chitpore Road, on the north side of Dalhousie Square in Calcutta, 1826. Aquatint, 11 x 16 in. Printed in Fraser's Views in Calcutta, Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

—. View of the Loll Bazaar opposite the house of John Palmer, Esq., ca. 1825-1826. Collection of the British Library.

Henry Lee (1782-1867), c. 1860, after a painting by Spiridione Gambardella (c. 1815-1886), c. 1840. Engraving, 23 x 16 cm; Courtesy of Henry Lee. Printed in Bean, Yankee India.

Solvyns, Balthazar (1760-1824). Market Scene, Calcutta, West Bengal. 1799. Etching with watercolor. Wellcome Collection. Image via JSTOR.

—. Calcutta Port and Vessels. 1794. Oil on panel, 67.3 x 121.5 cm. Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Museum. https://jstor.org/stable/community.1122357.