The Hatch and Brood of Time Volume I: September 28, 2020

By London Johns

Mark Antony calls to “let slip the dogs of war”; Richard II curses “dogs easily won to fawn on any man”; Celia insists that Rosalind’s words are “too precious to be cast away upon curs.” The similarity between almost every mention of dogs in Shakespeare’s plays is their distaste for the creatures. When dogs are not mercilessly violent, they are lazy; when not skirting their jobs, they feign loyalty for their own benefit. Shakespeare seems to dwell on dogs’ worst traits, and there are enough scornful mentions in his plays that it is tempting to assume that Shakespeare himself disliked them. Shakespeare’s apparent distaste for dogs is deeply rooted in the way that working dogs were perceived in Elizabethan culture. Each rank of dogs in society, from kitchen dogs to nobles’ hunting dogs, is portrayed in Shakespeare’s plays in a different way, and the traits they represent are as varied as the breeds of dogs themselves.

The first kind of working dog that Shakespeare mentions in his plays is a “curtal” or “curtail” dog, or a dog whose tail has been docked. This phrase is mentioned briefly in Act II Scene I of The Merry Wives of Windsor: Pistol tells Ford that “hope is a curtal dog in some affairs” in response to Ford’s hope that Falstaff has not pursued his wife. This line likely refers to a kitchen dog rather than a hunting dog, as hunting dogs’ tails were needed for running and would not typically be docked. “Curtal” may carry the connotation of a common man’s rather than a nobleman’s animal; thus hope is not only a dog, but a particularly ordinary one. This cynical view of hope is solidified by Pistol’s reference to the myth of Actaeon, who was transformed into a stag by Artemis and torn apart by his own hounds.

Shakespeare also uses the phrase “curtal dog” in The Comedy of Errors. Dromio of Syracuse complains to Antipholus that Luce could have “transformed [him] to a curtal dog and made [him] turn i' th' wheel.” As a servant working in the kitchen, Luce would have been familiar with curtail dogs, and would likely have set several to work as turnspit dogs. Turnspits were small working dogs commonly found in kitchens beginning in the 16th century. Their role was to run in a suspended wheel connected to a spit, and their motion would keep the spit turning in order to cook meals over a fire. As Of Englishe Dogges, the earliest known English work on dog breeds, described their role in 1576:

“There is comprehended, vnder the curres of the coursest kinde, a certaine dogge in kytchen seruice excellent. For whe any meate is to bee roasted they go into a wheele which they turning rounde about with the waight of their bodies, so diligently looke to their businesse, that no drudge nor skullion can doe the feate more cunningly.”

Of Englishe Dogges praises turnspit dogs for their abilities. However, these animals were not always described in such complimentary terms. Kitchen workers would often throw hot coals into the turnspit’s wheel to force them to continue moving or suffer painful burns, and though the dogs were able to work in shifts, each was made to run for several hours at a time. Grueling work and constant abuse resulted in turnspit dogs being known for their bad temper. John Cordy Jeaffreson, a 19th-century novelist, called them “distorted… and graceless,” hated by everyone in the kitchen and aggressive towards every creature, including other turnspit dogs:

“Of all living creatures, your true turnspit dog detested none more ferociously and implacably than his fellow turnspit. Abused by men of all degrees, and scorned by every other ‘dog of the house,’ a pair of turnspits were continually snarling at and fighting each other… and in their mutual rage they would sometimes fight to the death. Buffon tells the story of a turnspit dog that, on escaping from the wheel in the Duc de Lianfort’s kitchen in Paris, ran in upon his fellow turnspit and killed him, because the latter had, by skulking, compelled him to perform an additional spell of work.”

This is likely the image that Shakespeare intends to convey through Dromio’s complaint. Instead of the tireless worker recorded in Of English Dogges, Shakespeare sees Jeaffreson’s violent mutt; Dromio could be trapped by Luce’s affection in a torturous existence, and Pistol tries to convince Ford that hope is an unpredictable and paranoid animal.

Though more favorable mentions of dogs are rare in Shakespeare’s plays, they do exist. In The Taming of the Shrew, the Lord and a Huntsman engage in a conversation that makes it clear that they are familiar and affectionate with the Lord’s hunting dogs. The Lord commands the huntsman to take care of his hounds, and then praises them each by name:

“Brach Merriman, the poor cur is emboss’d;

And couple Clowder with the deep-mouth’d brach.

Saw’st thou not, boy, how Silver made it good

At the hedge-corner, in the coldest fault?

I would not lose the dog for twenty pound.”

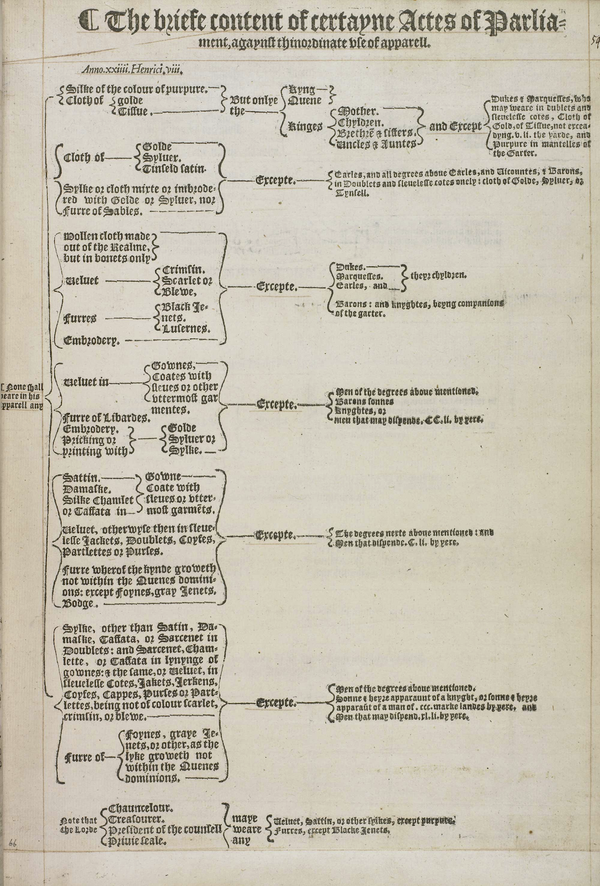

Not only does the Lord know the names of all of his dogs, but he is able to identify their specific strengths and values them greatly. His dogs are, in fact, just as valuable to him as his servants; servants’ wages at that time were unlikely to break sixty pounds a year. This kind of respect for hunting dogs and for the sport of hunting was common in this period. George Turberville’s 1576 Booke of Hunting documents hunting practices of the time, and spends several pages on the identification of “good and fayre” hounds. As well as typical physical characteristics, Turberville recommends ensuring that the dog “feareth neither water nor colde,” with large nostrils that suggest “a dogge of perfect sent.” The book outlines the relationship between hunter and hunting dog and recommends ways for hunters to guide their dogs. It paints a picture of animal-human cooperation much deeper than the use of turnspit dogs.

The veneration shown toward hunting dogs in Shakespeare’s plays could not be more different from the disdainful way in which Shakespeare writes about “curtal dogs” in The Merry Wives of Windsor and The Comedy of Errors. This disparity in the way that Shakespeare writes about dogs conveys a similar disparity in the Elizabethan view of different types of dogs. Turnspit dogs were worth very little; some hunting dogs achieved a rank close to human nobility. Their status is used as encouragement in Shakespeare’s Henry V:

“Let us swear

That you are worth your breeding, which I doubt not,

For there is none of you so mean and base

That hath not noble lustre in your eyes.

I see you stand like greyhounds in the slips,

Straining upon the start. The game's afoot.”

Henry’s soldiers endeavor to be as swift and determined as their dogs, who carry the same “noble lustre.” In Shakespeare’s plays, these animals are not only the nobility of dogs, but the physical embodiment of desirable traits -- haste, agility, strength, focus. As greyhounds embody certain ideal traits, turnspit dogs embody undesirable ones.

It is tempting to assume, from the wealth of derisive dog-related metaphors in Shakespeare’s plays, that he personally disliked them. However, to the extent that one can extrapolate any details of Shakespeare’s own opinions from his plays, one finds the opposite to be true. His curtail dogs are chaotic and violent, his greyhounds swift and precise; one can find no standard distaste for all dogs in his plays, rather a distaste for the traits that curtail dogs represent. Shakespeare’s dogs are as varied as the dogs that Macbeth described to the two murderers: “The valued file/Distinguishes the swift, the slow, the subtle,/The housekeeper, the hunter, every one/According to the gift which bounteous nature/Hath in him closed.”

Works Cited

Caius, John. Of Englishe Dogges. Translated by Abraham Fleming, A. Bradley, 1576. pp. 34-35

Harper, Charles. The Old Inns of Old England: A Picturesque Account of the Ancient and Storied Hostelries of Our Own Country, Volume 1. Chapman & Hall, 1906. p. 49.

Jeaffreson, John. A Book About the Table. Internet Archive. Retrieved 26 September 2020. Pp. 251-252.

Nares, Robert. A Glossary: Or, Collection of Words, Phrases, Names and Allusions to Customs, Proverbs, Etc. Which Have Been Thought to Require Illustration, in the Works of English Authors. Cambridge University Press, 2011. p. 115.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Translated by Arthur Golding. William Seres, 1567. P. 60.

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 35

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. P. 87.

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 113

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. P. 87.

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 119

Shakespeare, William. The Comedy of Errors. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 81.

Shakespeare, William. The Merry Wives of Windsor. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 53

Shakespeare, William. The Taming of the Shrew. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/. p. 8.

Turberville, George. Booke of Hunting. Internet Archive. Retrieved 26 September 2020. p. 15. Wigstead, Henry. Remarks on a Tour to North and South Wales: In the Year 1797. Internet Archive. Retrieved 26 September 2020. p. 53.