Volume 12: December 14, 2020

Ophelia's Distraction

By London Johns

In Act IV, Scene 5 of Hamlet, Ophelia enters distracted. She sings suggestive folk songs and speaks in riddles. Two scenes later she has died, quietly and offstage. Ophelia’s madness, as brief as it is in the play, became an iconic example of female mental illness in literature, and her death an unforgettable and constantly reproduced image. In the nineteenth century, a romanticized version of Ophelia’s downfall created a category for real mentally ill and socially unacceptable women and humanized asylum patients, allowing them to be the recipients of both newfound empathy and artistic scrutiny.

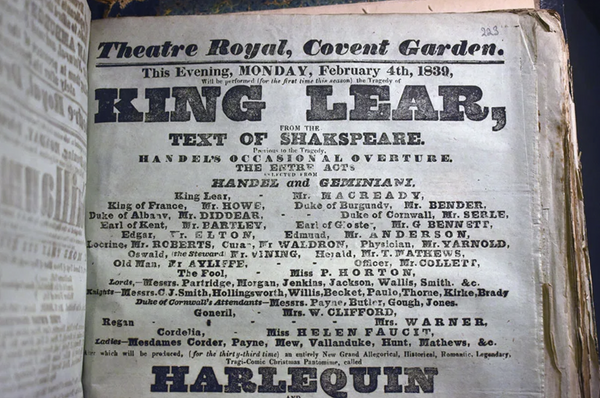

Ophelia was romanticized in nineteenth-century art. In paintings, she was often depicted in the scene of her death, floating peacefully among flowers as if asleep. Most famously, Millais’s 1852 painting of Ophelia showed her lying serenely in water, hands upturned (Stewart). This portrait and others, like Dicksee’s painting of a pale, ghostly Ophelia or any of Waterhouse’s various Ophelias, brought out her innocence, youth, and beauty rather than any ugliness of her madness. If she appeared distressed, it was subtle, conveyed in a facial expression rather than in the entirety of the portrait. This beautiful disguise cannot be entirely true to the Ophelia of Hamlet. Though Gertrude described her death as calm and “mermaid-like”, Ophelia must have been visibly unstable enough for Laertes to recognize her mental state from the moment she stepped into the room: when she entered in Act IV Scene V, he did not give her a chance to speak before exclaiming that her “madness shall be paid with weight/Till our scale turn the beam” (Shakespeare 235; 217). Depictions of her death in 19th-century art neglected the socially unacceptable aspects of her insanity in favor of her beauty and victimhood. The resulting romanticized iconography made her a valuable tool for Victorian mental hospitals, enabling psychiatrists to treat Ophelia as the face of mental illness in young women. “Ophelia is the very type of a class of cases by no means uncommon,” an English psychiatrist named J. C. Bucknill wrote in 1859. “Every mental physician of moderately extensive experience must have seen many Ophelias. It is a copy from nature, after the fashion of the Pre-Raphaelite school” (qtd. in The Female Malady 90). By “the Pre-Raphaelite school”, Bucknill was referring to the art movement that included Millais, Hughes, and Waterhouse, cementing the connection between artistic and psychiatric portrayals of Ophelia. Instead of being demonized, young women in Victorian asylums could become empathetic figures by aligning with Ophelia’s image -- whether or not her madness was accurate to their own struggles.

The similarities between real patients and the idea of Ophelia were sometimes crafted by their doctors. From 1848 to 1858, Dr. Hugh Welch Diamond, the director of the Surrey County Asylum, photographed his female patients. He hoped to use the photographs to determine patients’ mental states using physiognomy, or the study of their facial features (“Hugh Welch Diamond”). Through his photographs and writing, Diamond encouraged his audience to expand physiognomy to include a patient’s entire appearance -- their clothing and hair as well as their face. However, though Diamond’s interest in physiognomy may suggest that his patients could choose how they appeared in portraits, that was likely not always the case. According to Showalter, this patient did not don her Ophelia-esque crown of flowers on her own. Instead, her clothes and pose were chosen by Diamond (The Female Malady 92). Though Diamond is best known for photographs of asylum patients, one of his non-asylum photographs is of Shakespeare’s house in Stratford-upon-Avon -- it is possible that his choice to allude to Hamlet was influenced as much by his own interest in Shakespeare’s plays as by other psychiatrists and asylum employees (“Shakespeare's House”). It seems fitting for him to be interested in theater; the act of dressing his patients as Ophelia and photographing them was similar to dressing up an actress for a play, as if madness was a performance or spectacle.

Diamond’s photographs did not necessarily paint an accurate picture of his patients’ situations, but they did help improve their lives. Diamond was a proponent of the ethical treatment of patients in asylums, and was particularly opposed to the use of restraints in treatment (Pearl 289). Though it wasn’t their primary purpose, his photographs assisted this cause by giving a human face to people whose struggles had not been depicted in the same way before, aided by the relatively new invention of the camera. The expressions and postures of his patients allowed their experiences to be seen publicly instead of kept behind the doors of the asylum.

As mental hospitals used the character of Ophelia to inform and change their perceptions of patients, actresses playing Ophelia used -- and were encouraged by asylum workers to use -- the mannerisms of mentally ill women to inform their own interpretations of the part. Dr. John Conolly, an asylum superintendent, wrote in 1863 that he had seen similarities to Ophelia in those who “die of a broken heart” (177): “the same young years, the same faded beauty, the same fantastic dress and interrupted song” (178). Therefore, he wrote, actresses taking on the role should come to asylums and observe patients in order to mimic their mannerisms. He went as far as to say that no actress could effectively play Ophelia without having spent time observing patients in an asylum:

“It seems to be supposed that it is an easy task to play the part of a crazy girl, and that it is chiefly composed of singing and prettiness. The habitual courtesy, the partial rudeness of mental disorder, the diminished consciousness of what is present and real, and the glimpses of acute observation, the sudden transitions … are things to be witnessed and reflected upon, things to be imagined only by a few. Without such observation or such imaginative power, an actress must fail.” (Conolly 179-180)

Conolly, like Diamond, believed in asylum reform. Because Ophelia had become such a well-known symbol, by criticizing performances of Ophelia, he could also criticize the way in which mentally ill women were perceived and represented in society.

Fifteen years later, actress Ellen Terry followed Conolly’s advice. She was to play Ophelia at the Lyceum Theatre, and decided to visit an asylum for inspiration. By that point, an asylum visit had probably become tradition for actresses preparing for the role; Terry wrote in her autobiography that she shared the idea with “all Ophelias before (and after)” her (169). Terry’s visit did not begin as well as she’d hoped. She found in the patients “no beauty, no nature, no pity,” and, ironically, found them “too theatrical” to inform her own theatrics, as if their madness was a performance (169). In other words, the real lives of mentally ill women did not match the image of Ophelia’s madness that Terry may have imagined. Nevertheless, Terry distinctly remembered two specific encounters that she had at the asylum. The first was a young woman who stood

“gazing at the wall. I went between her and the wall to see her face. It was quite vacant, but the body expressed that she was waiting, waiting. Suddenly she threw up her hands and sped across the room like a swallow. I never forgot it. She was very thin, very pathetic, very young, and the movement was as poignant as it was beautiful.” (Terry 169)

The second patient that Terry remembered was a woman who laughed despite displaying no emotion on her face except “pathetic and resigned grief” (169). The image of these two women -- of young, beautiful, “distracted” girls, decidedly victims -- aligned with what would become the most common interpretation of Ophelia for the next century (“Ophelia, Gender and Madness”). It also aligned with the traits that John Conolly mentioned as important to observe in patients. The first girl that Terry noticed certainly displayed “sudden transitions”, and her inability to recognize Terry’s face could have indicated a “diminished consciousness of what is present and real”; the second woman perhaps acted with “habitual courtesy” in laughing automatically, and her “pathetic… grief” calls to mind what Conolly named Ophelia’s “pathetic lamentation” at the end of Hamlet (23).

The idea of mentally ill women as Ophelia-like figures, and of Ophelia as an asylum patient, was typically pushed by male doctors. However, some actresses stopped looking to asylums for inspiration for their interpretations of Ophelia and began to look inward, using Ophelia’s character as a channel for their own experiences. Ellen Terry ultimately decided to deviate from the typical interpretation of Ophelia, playing her as a victim of sexual harassment and paving the way for future feminist interpretations (“Ophelia, gender and madness”). Ophelia became an empty vessel to hold whatever it needed to, from righteous anger to tragic martyrdom.

Works Cited

Conolly, John. A Study of Hamlet. E. Moxon & Company, 1863.

“Hugh Welch Diamond (British, 1809 - 1886) (Getty Museum).” The J. Paul Getty Museum, The J. Paul Getty Museum, www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/1805/hugh-welch-diamond-british-1809-1886/.

Pearl, Sharrona. “ Through a Mediated Mirror: The Photographic Physiognomy of Dr Hugh Welch Diamond.” History of Photography, vol. 33, no. 3, 2009.

“Shakespeare's House (Getty Museum).” The J. Paul Getty Museum, The J. Paul Getty Museum, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/205510/hugh-welch-diamond-shakespeare's-house-british-1854-1856/.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Edited by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, The Folger Shakespeare, shakespeare.folger.edu/.

Showalter, Elaine. “Ophelia, Gender and Madness.” The British Library, The British Library, 6 Nov. 2015, www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/ophelia-gender-and-madness.

Showalter, Elaine. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830-1980. Penguin Books, 1987.

Stewart, Rachel. “Ophelia in Nineteenth-Century English Art, Inspired by John Everett Millais.” Shakespeare & Beyond, Folger Shakespeare Library, 18 Jan. 2018, shakespeareandbeyond.folger.edu/2018/01/30/ophelia-nineteenth-century-english-art/.

Terry, Ellen. The Story of My Life: Recollections and Reflections . Doubleday, Page & Co., 1908.

Window, Frederick Richard, and William Henry Grove. “Ellen Terry as Ophelia in 'Hamlet'.” National Portrait Gallery, National Portrait Gallery, 2007, www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw135893/Ellen-Terry-as-Ophelia-in-Hamlet.