The Hatch and Brood of Time Volume 2: October 5, 2020 By London Johns

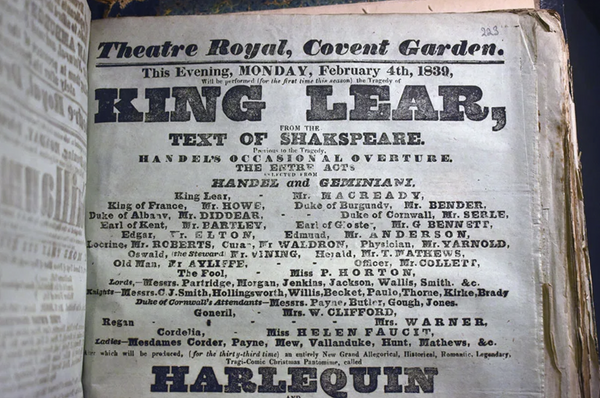

In 1660, King Charles II returned from France, reestablishing the Stuart monarchy in England and bringing with him a wave of new ideas and practices with the beginning of the Restoration. Along with reopening the theaters that closed after the English Civil War, this era introduced the first professional actresses to the English stage. From the very first play to include a female actress, Thomas Killigrew’s Vere Street Theatre production of Othello in 1660, Shakespeare’s works provided opportunities for women to take up the new position of professional actress. In return, Restoration audiences’ obsession with actresses’ sexuality resulted in new and increasingly indecent adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays.

The first English actresses came to the stage in 1660, the year of the restoration of the monarchy. Charles II had several reasons to permit women to perform. First, Restoration audiences were concerned about inappropriate content in plays, and assumed that the inclusion of women in drama would force its content to become more tame. In Charles’s letter granting two theaters the right to employ female actresses in 1662, he wrote that “passages offensive to piety and good manners” should not be performed, and that women could act onstage only as long as their plays portrayed “useful and instructive representations of humane life” (qtd. in Dodsley clxxv). Second, Charles was likely inspired by actresses he encountered while in exile in France. Unlike English actresses, there are records of professional French actresses dating back to the early 17th century. Thomas Jordan’s 1660 “Prologue to introduce the first Woman that came to Act on the Stage…” asked why England must “count that a crime France calls an honour?/In other Kingdoms Husbands safely trust 'm,/The difference lies onely in the custom” (22). Jordan’s primary concern seemed to be introducing actresses to scandalized audiences, and French theatre acted as useful precedent. Lastly, Charles wrote that some audiences had “taken offence” at women’s parts being “acted by men in the habits of women” (qtd. in Dodsley clxxv); this suggests a fear that male actors playing women were portraying homosexuality onstage.

The first known professional English actress played Desdemona in the Vere Street Theatre’s production of Othello in 1660. Her name is not known for certain, though there have been several candidates; until recently, the leading theory of her identity was successful actress Margaret Hughes, though it now seems more plausible that it was instead Ann Marshall, who according to John Downes’s Roscius Anglicanus was a member of Thomas Killigrew’s company at the time (48). These new English actresses became the subjects of much public attention, quickly rising to a level of stardom not experienced by most actors in the Elizabethan or Jacobean eras. Male audiences were particularly fixated on their sexuality. Actresses were commonly linked to prostitutes, and theaters to brothels. Robert Gould complained in his Satyr on Players that an actress would “prostitute with any,/Rather than wave the getting of a penny” (181). If an actress was thought of as particularly chaste, her sexuality would be equally examined; Mrs. Bracegirdle, an actress described (perhaps ironically) as the “celebrated virgin,” is described in A Comparison Between the Two Stages (qtd. in Highfill) as “a haughty conceited Woman, that has got more Money by dissembling her Lewdness, than others by professing it” (Highfill 278). The actions of actresses were inconsequential; whether they conformed to or resisted the expectations placed on them by their audiences, they remained constantly criticized for their appearances and personal lives as much as their performances.

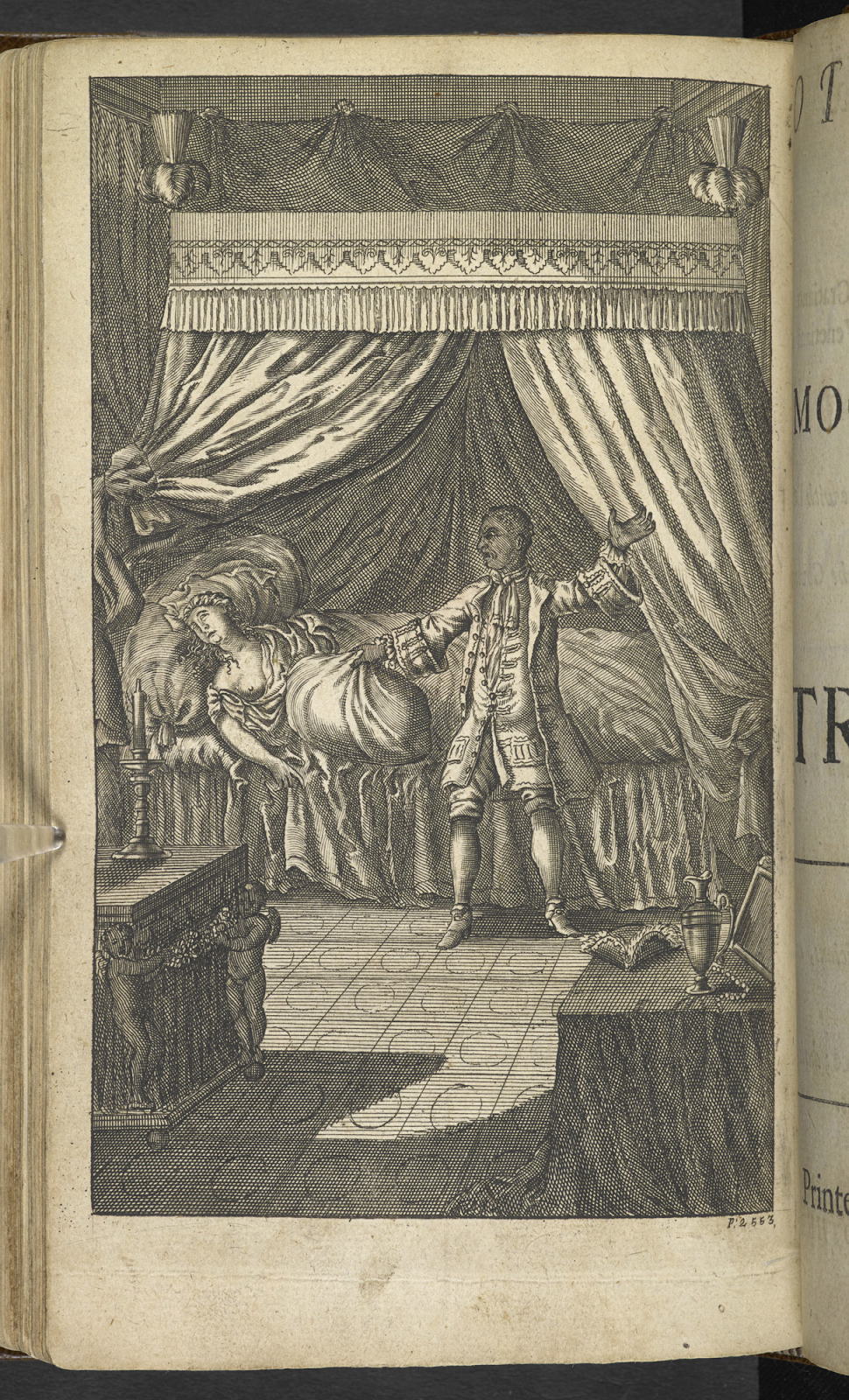

The hypersexualization of professional actresses during the Restoration twisted a potentially liberating development -- the ability of women to perform onstage -- into an opportunity to objectify and sexualize women’s bodies. The same happened to another aspect of 17th century theatre: “breeches roles”. Breeches roles were roles in which women wore male clothing. They were particularly common in the form of characters like Viola in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, where a woman temporarily disguised herself as a man until her true identity was revealed at the end of the play (Howe 59). These roles not only required women to wear revealing clothing that would not be deemed acceptable in the rest of their lives, but also resulted in gratuitous scenes of nudity wherein an actress would bare her chest to prove her gender (Howe 59). One example of this kind of scene can be found in Aphra Behn’s 1696 play The Younger Brother, in which a woman dressing as a male page has her chest revealed not once, but twice in a single scene:

“The Prince helding Olivia by the Bosom of her Coat, her Breast appears to Mirtilla.

Mir.

Ha! what do I see?— Two Female rising Breasts. By Heav'n a Woman.— Oh fortunate Mischance.

[…]

Prince.

Talk on, false Woman! till thou hast perswaded my Eyes and Ears out of their native Faculties, I scorn to credit other Evidences.

Mir.

Try 'em once more, and then repent, and dye.

Opens Olivia's Bosom, shews her Breasts.

Prince.

Ha— by Heav'n a Woman!” (Behn 48)

Scenes like this were incredibly common. In fact, breeches roles appeared in nearly a quarter of London’s plays between 1660 and 1700, and some pre-Restoration plays that did not originally have breeches roles were adapted to include them (Howe 57).

Many of the plays adapted to include breeches roles or female nudity were Shakespeare’s. Scenes centered around the bodies of female characters were originally unfeasible in Shakespeare’s plays. It would be difficult to convince an audience to believe, for instance, that the body of the young male apprentice playing Rosalind in an Elizabethan theater would be sufficient to convince Orlando of her identity. However, the introduction of women to the stage created the possibility of visible female bodies, and Restoration playwrights exploited that possibility to the fullest extent. They sometimes forced entirely new roles into plays that had no need for them, as was the case in John Crowne’s adaptation of Henry VI, Parts II and III (Howe 57). The added character, Lady Elianor, dresses as a male soldier and is killed by Edward:

“Enter Lady Elianor in mans habit [...] La. El. and Ed. Fight, La. El. falls.

Ed.

VVhat bold young man is this?

Thou art dispatch'd, I wonder who thou art.

La. El.

Look on me well—see if thou dost not know me.

Ed.

May I believe my eyes!” (Crowne 63)

The popularity of scenes including naked and cross-dressing women resulted in the addition of various forms of these scenes to Restoration plays and pre-Restoration adaptations alike. One particularly distinctive aspect of this trend was the introduction of new rape scenes to Shakespeare’s plays.

Rape was a common theme in Restoration theater, enough that the term “she-tragedy” was coined to refer to the fashionable plays of this period about the downfall of defenseless women (Tumir 411). According to Elizabeth Howe, rape scenes were added in Restoration adaptations of both Coriolanus and King Lear (46). Thomas D’Urfey added a rape subplot to his adaptation of Cymbeline; Clarina, Eugina (Imogen)’s confidant, is accused of helping Eugina and is sentenced to be raped and hanged (Howe 46). Before she is sentenced, Clarina insists her own innocence:

“Oh do not fright me with the name of Death!

But look with pity, Madam, on my tears,

And see a wretched Virgin beg for Life:

So may your Raign be prosp'rous, so your Beauty

Still fresh and heavenly, as your mercy flows

In showers of tender pity on my youth.” (D’Urfey 33)

Clarina is portrayed as young, naive, and utterly powerless. This seems to draw in her tormentor, Iachimo, who mocks her by saying, “Weep soundly; it makes the flame of Love more/Vigorous” (Durfey 38). The addition of this scene adds little to the plot of the play, but utilizes several of the tropes used in scenes of sexual assault in plays of this era: a powerless woman, a predatory man, and, strangely enough, the presence of another close friend or family member in the scene. As Howe pointed out about a similar scene in a 1696 play, the rape subplot functions more as a “pornographic painting brought to life” than a functional part of the play. (46)

The initial reasons to allow women to act onstage in England were rooted in the desire to cleanse Restoration theatre of the perceived moral offenses of Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre. However, instead of causing playwrights to be cautious in the subject matter explored in their works, the introduction of the first actresses prompted a new cultural fixation with the very traits in theatre that the change was meant to eliminate in the first place: sexuality, prostitution, and cross-dressing. The new theatre culture provoked new kinds of adaptations of Shakespeare plays, drawing in audiences and public attention to his work. Though Restoration interpretations of Shakespeare’s works were perhaps not as faithful to his original plays as future interpretations, the attention that they brought to his work strengthened his reputation as a poet and extended his influence into the 18th century.

Works Cited

Behn, Aphra. The younger brother, or, The amorous jilt a comedy : acted at the Theatre Royal by His Majesty's servants / written by the late ingenious Mrs. A. Behn ; with some account of her life. Printed for J. Harris ... and sold by R. Baldwin ..., 1696. Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A27334.0001.001, accessed 4 October 2020.

Crown, John. The misery of civil-war a tragedy, as it is acted at the Duke's theatre, by His Royal Highnesses servants / Mr. Crown. London: Printed for R. Bentley and M. Magnes, 1680. Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A35289.0001.001, accessed 4 October 2020.

Dodsley, Robert. A Select Collection of Old Plays. Vol. 1, S. Prowett, 1825.

Downes, John. Roscius Anglicanus: Or, An Historical Review of the Stage From 1660 to 1706. London: J.W. Jarvis & son, 1886.

D'Urfey, Thomas. The injured princess, or, The fatal vvager. London: Printed for R. Bentley and M. Magnes. Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/a36983.0001.001, accessed 4 October 2020.

Gould, Robert. Poems, chiefly consisting of satyrs and satyrical epistles by Robert Gould. London: Printed, and are to be sold by most booksellers in London and Westminster, 1689. Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A41698.0001.001, accessed 5 October 2020.

Highfill, Philip, et al. A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800. Vol. 1-2, SIU Press, 1973.

Howe, Elizabeth. The First English Actresses: Women and Drama, 1660-1700. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Jordan, Thomas. A royal arbor of loyal poesie consisting of poems and songs digested into triumph, elegy, satyr, love & drollery. Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A46270.0001.001, accessed 4 October 2020.

Lely, Peter. “Portrait of Margaret Hughes.” Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, 2020, museum.cornell.edu/collections/european/european-art-1600-1900/portrait-margaret-hughes.

Shakespeare, William. The Works of Mr. William Shakespear; in Six Volumes. Adorn'd with Cuts. Revis'd and Corrected, with an Account of the Life and Writings of the Author. Edited by N. Rowe, 1709.

Tumir, Vaska. “She-Tragedy and Its Men: Conflict and Form in The Orphan and The Fair Penitent.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 30, no. 3, 1990, pp. 411–428. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/450704. Accessed 5 Oct. 2020.