Volume 2 of The Printed Past

Print and the Persecution of Witchcraft

By Ava Hathaway Hacker

Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in 1450 has often been hailed as the birth of widespread knowledge dissemination. Using movable type, the press was capable of quickly reproducing text, and, in the following years, the technology spread from its place of origin (Mainz, Germany) across Europe. By the end of the 1400s, there were presses in sixty out the hundred largest European cities.[1]

From the outset, Christianity and the press were deeply intertwined, not only in the production of the famed Gutenberg bible, which was being sold by 1455, five years after the press’s invention, but in the Church’s production of a vast array of materials, including indulgences, ordinances, propaganda, and liturgical books.[2] It is no surprise that the most powerful institutions in society were the most represented in popular print. But what may be less expected is the way in which the rapid dissemination of the written word allowed by the new printing press became a mechanism for inspiring mass panic and building support for the Church by marshaling the public to work against a common enemy: witchcraft.

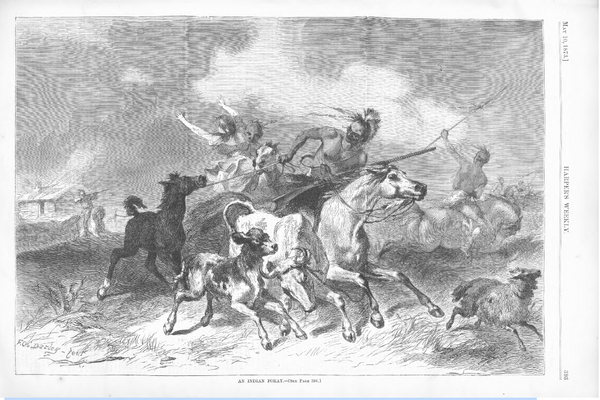

At the time the press was invented, the Catholic Church had attacked the idea of witchcraft and sorcery for centuries. Around 900 C.E., the Canon episcopi condemned any who believed in the falsehood of magic, charging that they had “been seduced by the Devil in dreams and visions into old pagan errors.”[3] Still, it was not until the 1400s that accusations of witchcraft became common, and increasingly so as the century progressed. Though texts on witchcraft had been published before, the 1487 publication of Malleus Maleficarum by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, would become by far the most widely read and impactful in Europe.[4] The Malleus, far from the denial of witchcraft found in the Canon episcopi, condemned any who did not believe in witchcraft for leaving themselves at the mercy of its treachery. It was a handbook, essentially, on how to identify witchcraft and witches, and also, crucially, how to condemn them. The “insatiable carnal lust” of women as well as their inherent weakness and susceptibility to sin made them far more likely to be witches, the authors claimed.[5] The connection between witchcraft and femininity was solidified in the Malleus, coinciding as well with a time in society where the average age of marriage was becoming older, resulting in a larger percentage of unmarried women in European society, and creating the perfect target for the Malleus’s accusations.[6]

Fig. 1. Title page of a 1580 edition of the Malleus.

Created just as presses were being established across Europe, the Malleus would become among the first books published with Gutenberg’s press. Soon, twenty editions of the text were in circulation.[7] In “Problems Inherent in Socio-Historical Approaches to the European Witch Craze,” Nachman Ben-Yehuda explains that “[t]he importance of the Malleus must not be underestimated. The extensive influence it wielded was guaranteed by its authoritative appearance, and its extremely wide distribution.” It became, in effect, “the text-book of the Inquisition.”[8]

The Malleus’s authors, Jakob Sprenger and Heinrich Kramer, were Dominican Inquisitors who had been specifically tasked by Pope Innocent VIII to counter the evils of witchcraft. A papal bull by Pope Innocent, Summis desiderantes affectibus, was published as the preface to the Malleus and gave jurisdiction to the authors to act as Inquisitors against witchcraft, asking all powers, Church and secular alike, to aid them in their holy quest.[9] The Malleus consistently identified the risk of sorcery to the Church, tying the power of witchcraft to its denial of Christianity and blasphemous, obscene devotion to the devil. A passage of the Malleus reads: “Mark well, too, that among other things, [witches] have to do four deeds for the increase of that perfidy, that is, to deny the Catholic faith in whole or in part through verbal sacrilege, to devote themselves body and soul [to the devil], to offer up to the Evil One himself infants not yet baptized, and to persist in diabolic filthiness through carnal acts with incubus and succubus demons.”

In Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance, Ben-Yehuda and Eric Goode write that “[b]y Persecuting witches, this society, led by the church, attempted to redefine its moral boundaries.” And the Church required a deviant power to set itself against, specifically "one which would be seen as directly threatening the religiously defined societal community and the Christian worldview."[10] Witchcraft was the perfect scapegoat for the Church, and the new technology of print was the perfect medium to aid it. As Ben-Yehuda explains, “with the insertion of the Summis desiderantes as its preface, the last impediment to the inquisitorial witch-hunt was removed.” Now, “[t]he moral backing had been provided for a horrible, endless march of suffering, torture, and human disgrace inflicted on thousands of women.”[11]

Though smaller witch hunts had been carried out before the Malleus’s publication, witchcraft began to be persecuted in full force during the 15th century in a frenzy that lasted until the 17th century. Ben-Yehuda identifies a shift in the 1400s from witchcraft being conceptualized as an everyday personal tool, equally possible to use for good or bad, to a purely evil and malicious force, a shift aided considerably by the Malleus.[12] By 1650, when the worst of the witchcraft persecution was coming to an end, somewhere between 200,000 and 500,000 accused witches, of whom the vast majority were women, had been condemned and killed in continental Europe (where the persecution was most virulent and widespread).[13]

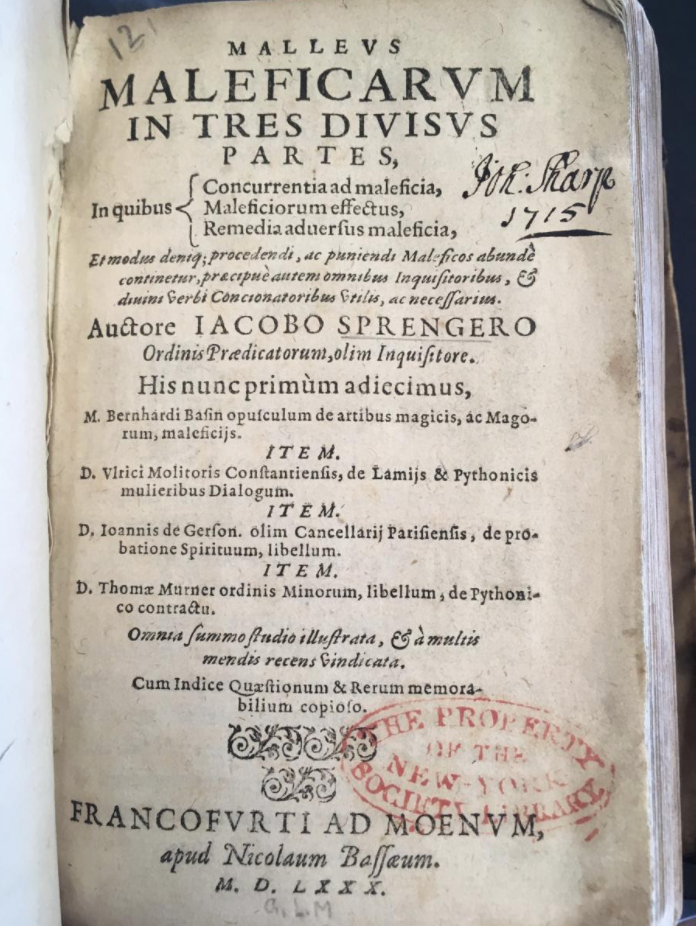

The Malleus had created the popular idea of the “witch” through the printed word, but the printed image would also play a crucial role in defining the visual imagery of witchcraft. Though the Malleus was a textual document without illustration, it helped make witchcraft a popular topic for artists across Europe. In the 16th and 17th century, a new publishing revolution occurred in Europe: Woodcut prints allowed quick and cheap dissemination of images to the popular masses.[14] Witchcraft was a popular topic of these unrefined, widely spread images, often in the form of single page broadsheets or pamphlets with woodcut illustrations and simple, inflammatory text. The visual medium allowed a far broader audience than even the widely read texts on witches. As Carla Suhr writes in “Publishing for the Masses: Early Modern English Witchcraft Pamphlets,” “witchcraft pamphlets were written with a specific audience in mind - the unlearned masses - though it did not preclude a more heterogeneous readership.”[15]

In 1579, one of the best known and first published of these pamphlets came into popular culture. This was A Rehearsall both Straung and True, of Hainous and Horrible Actes Committed by Elizabeth Stile, alias Rockingham, Mother Dutten, Mother Deuell, Mother Margaret, Fower Notorious Witches. The pamphlet told of Elizabeth Stile, a sixty-five-year-old widow from the town of Windsor who was accused of being a witch and who implicated in her confession the other three women named in the pamphlet’s title. The pamphlet explained in lurid detail the horrific deeds of the accused women—from inflicting illness to committing murder to feeding their own blood to animal familiars whom they often unleashed on others.[16] The text was accompanied by illustrations depicting some of the described scenes. Pamphlets such as these circulated throughout the following century in what Suhr calls “part of the efforts to ‘re-Christianize’ England,” similar to the use of the Malleus by the Church in continental Europe to create a common enemy in service of empowering the Church.[17]

The role of print media in both greatly exacerbating the persecution of witchcraft and in creating the popular image of witchcraft in European society that persisted for centuries to come reveals the power of print not only to reflect its historical moment but to deeply, and irrevocably, shape it.

Fig. 2. Image of a witch feeding her blood to her familiars. From A Rehearsall both Straung and True, of Hainous and Horrible Actes Committed by Elizabeth Stile, alias Rockingham, Mother Dutten, Mother Deuell, Mother Margaret, Fower Notorious Witches (1579).

Rubin, Jared, "Printing and Protestants: An Empirical Test of the Role of Printing in the Reformation," The Review of Economics and Statistics 96, no. 2 (2014): 270-86, Accessed March 28, 2021, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43554930, 271. ↩︎

Ibid, 272. ↩︎

Project Gutenberg, “Malleus Maleficarum,” accessed March 28, 2021, http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/eng/Malleus_Maleficarum. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Nachman Ben-Yehuda, “The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist's Perspective,” American Journal of Sociology 86, no. 1 (July 1980): pp. 1-31, https://doi.org/10.1086/227200, 11. ↩︎

Ibid, 21. ↩︎

Ibid, 11. ↩︎

Ibid, 11. ↩︎

Jane Schuyler, “The ‘Malleus Maleficarum’ and Baldung's ‘Witches' Sabbath,’” Source: Notes in the History of Art 6, no. 3 (1987): pp. 20-26, https://doi.org/10.1086/sou.6.3.23202318, 20. ↩︎

Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda, Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), https://books.google.com/books?id=SbY2Mksi1kcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, 184. ↩︎

Ben-Yehuda, “The European Witch Craze,” 11. ↩︎

Ibid, 3. ↩︎

Ibid, 1. ↩︎

Jon Crabb, “Woodcuts and Witches,” The Public Domain Review, May 4, 2017, https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/woodcuts-and-witches#1-0. ↩︎

Suhr, Carla, "Publishing for the Masses: Early Modern English Witchcraft Pamphlets," Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 113, no. 1 (2012): 118-21, Accessed March 28, 2021, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43344555, 118. ↩︎

Crabb, “Woodcuts and Witches.”; “Witchcraft Pamphlet: A Rehearsal Both Strange and True, 1579,” The British Library (The British Library, September 22, 2015), https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/witchcraft-pamphlet-a-rehearsal-both-strange-and-true-1579#https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/woodcuts-and-witches. ↩︎

Suhr, “Publishing for the Masses,” 118. ↩︎

Bibliography

Ben-Yehuda, Nachman. “The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist's Perspective.” American Journal of Sociology 86, no. 1 (July 1980): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/227200.

Broedel, Hans Peter. The 'Malleus Maleficarum' and the Construction of Witchcraft Theology and Popular Belief. Manchester u.a.: Manchester University Press, 2009. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/35002/341393.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Crabb, Jon. “Woodcuts and Witches.” The Public Domain Review, May 4, 2017. https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/woodcuts-and-witches#1-0.

Goode, Erich, and Nachman Ben-Yehuda. Moral Panics: the Social Construction of Deviance. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. https://books.google.com/books?id=SbY2Mksi1kcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Gutenberg, Project. “Malleus Maleficarum.” Accessed March 28, 2021. http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/eng/Malleus_Maleficarum#cite_note-FOOTNOTETrevor-Roper1969102%E2%80%93105-9.

Rubin, Jared. "Printing and Protestants: An Empirical Test of the Role of Printing in the Reformation." The Review of Economics and Statistics 96, no. 2 (2014): 270-86. Accessed March 28, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43554930.

Schuyler, Jane. “The ‘Malleus Maleficarum’ and Baldung's ‘Witches' Sabbath.’” Source: Notes in the History of Art 6, no. 3 (1987): 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1086/sou.6.3.23202318.

Suhr, Carla. "Publishing for the Masses: Early Modern English Witchcraft Pamphlets." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 113, no. 1 (2012): 118-21. Accessed March 28, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43344555.

“Witchcraft Pamphlet: A Rehearsal Both Strange and True, 1579.” The British Library. The British Library, September 22, 2015. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/witchcraft-pamphlet-a-rehearsal-both-strange-and-true-1579#https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/woodcuts-and-witches.

Bibliography of Images

Fig. 1. Bieck, Barbara. “Library Blog.” Malleus Maleficarum: The Hammer of Witches | New York Society Library, October 19, 2020. https://www.nysoclib.org/blog/malleus-maleficarum-hammer-witches.

Fig. 2. Crabb, Jon. “Woodcuts and Witches.” The Public Domain Review, May 4, 2017. https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/woodcuts-and-witches#1-0.