by Liam Sheehan, Susquehanna University '21

Advised by Dr. Edward Slavishak

Edited by Grace Blaxill and Gage Denmon

INTRODUCTION

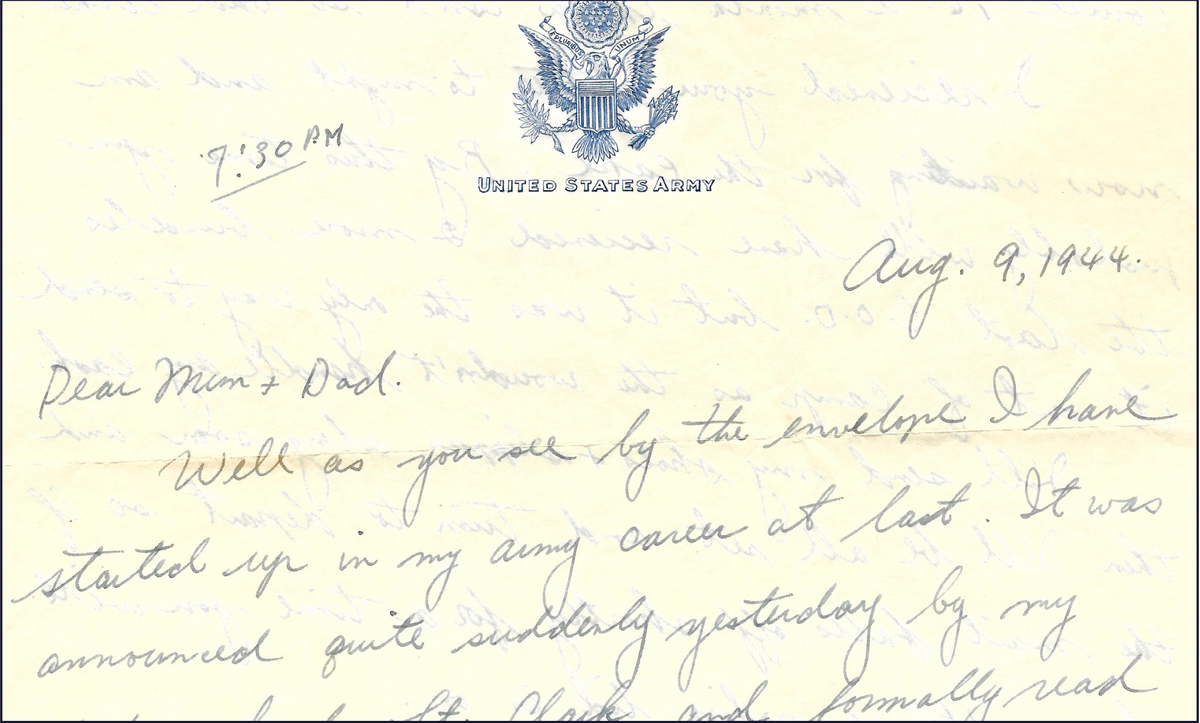

1944 was a year of goodbyes for most families in America. This was the case for John Moynagh as he wrote to his parents a few days before his deployment to France. The past three years had sent millions of men to foreign shores to fight and die for their country. The herculean under- taking of dragging American culture out of its Depression-era mindset and into one suited for war had taken the Roosevelt administration years and required a vast network of propaganda to imbue every aspect of life with a war mentality. It required a total reconstruction of what it meant to be an American as well as the conventional values of American patriotism. Improvements in newspapers and radio as conveyors of mass media allowed for this new image of American culture to be spread rapidly throughout the nation. Yet in order to understand how this cultural shift took hold, we must look deeper than the masses of men and women seen on the newsreels putting all of their effort into the war and instead focus on the individual, a single cog in the massive machine of history.

Through letters, photos, and postcards, the men and women involved in the Second World War informed their family and friends about the state of the nation’s efforts and were informed in turn of the efforts of their loved ones back home. These letters offered a moment of repose, a time to reflect on and record what they had witnessed. Yet not even the act of writing a letter home to mom and dad was completely free from the all-encompassing grasp of the war. Censorship of communications was paramount within military operations, and those overseas wrote everything with the eye of the censor in mind. However, there was a second, more sensitive type of censorship involved in the acts of letter-writing, one of a more social nature. Hopes, dreams, and—most importantly—fears had to abide strictly to the newly crafted wartime culture that the Roosevelt administration produced. New cultural norms of equating masculinity with a desire to serve the nation had been created within New Deal organizations and carried into the war. Adherence to this mindset dictated what could be shared and what must be kept confidential. Through this careful screening of text and emotion emerged the identity of the soldier-writer. Not a raw and unabridged identity, but an image carefully crafted for those at home within the lines of a few short pages. Though war is often depicted as a raging inferno of death and destruction, its fire also offers those involved a forge, within which they can create an identity of their own in the most stressful and chaotic time of their lives.

What authors leave behind in their letters, and perhaps more importantly what they omit, offers the historian a chance to see what they reveal about themselves to others, intentionally or not, and how they choose to write their identity. This paper is a case study of a single soldier, using his personal correspondences to follow him through his life during the prewar years, his various training stages, his experiencing the horrors of war, and his role post-hostilities. Through the lens of evolving ideals of American masculinity, this paper will examine how letter-writing can reveal the pressures of macroscopic, national changes on the individual identity of an American man.