By Marina Albanese, PC 20'

Advised by Professor Stuart Semmel

Edited by Frank Lukens, ES 22'

Julianna Gross, DC 23'

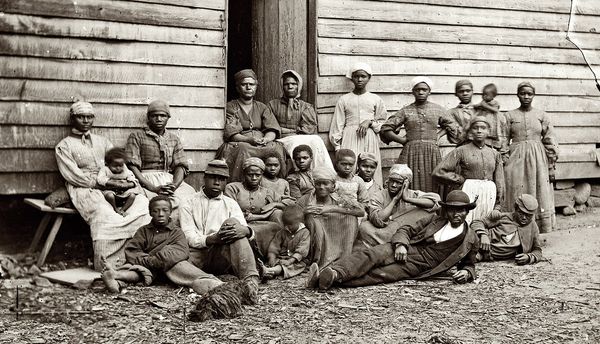

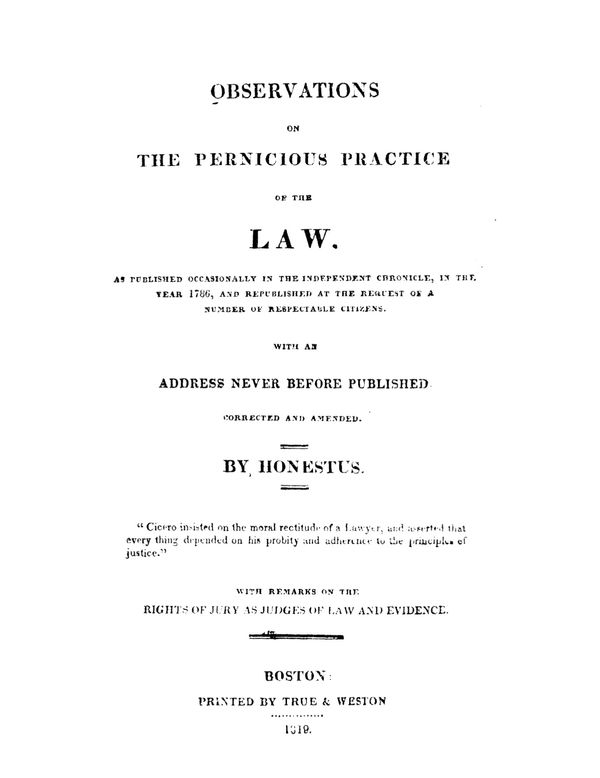

Historians have differed in their treatment of Josephine Butler (1828-1906), the Victorian feminist who led campaigns against regulated sex work in Britain, across Europe, and in Britain’s colonies. Butler emerges sometimes as global humanitarian, for her calls for international solidarity; sometimes as imperial feminist, for her Othering of colonized women; and sometimes as middle-class moralizer, for her desire to “rescue” working class sex workers. Taking these differing interpretations into account, I frame Butler’s campaigns as an aspiring human rights movement. I justify this treatment by analyzing Butler’s public writings and speeches and showing how she established a responsibility for white Western women to intervene in the lives of vulnerable women across the world, particularly poor women and women of color. Butler justified such responsibility by locating the injustice of regulated sex work in its violation of the human rights of all women.

At a time when rights discourse was grounded in “the rights of man,” Butler stressed the rights of humans and the inclusion of women, white and non-white, within this category. However, though being “human” created a commonality between the sex worker and the middle-class British feminist, it did not automatically mean a sameness.

In fact, as Butler bestowed humanity upon poor Western sex workers and non-white colonized women, she formulated what it actually meant to be “human.” I find that the humanity that Butler configured for the sex worker was a precarious one. In Butler’s accounts, sex workers appear as infantilized, animalistic or deadened, barely holding onto a minimum level of humanity. Butler thus situated the sex worker on a threshold. The sex worker tentatively possessed humanity, but in certain cases, she could be denied it. I identify these cases as instances when the sex worker did not embody a model of humanity defined by the conditions prescribed by Victorian feminist ideology.

Though both the Western and the colonized sex worker had to meet these conditions—primarily of innocence and shame—it was more important for the colonized, non-white woman to affirm them. Intimately tied together, innocence and shame provided a model of womanhood that, if emulated, brought the sex worker closer to the womanhood, as well as to the humanity, of the Western feminist. If a woman did not approach this model that reflected “civilizedness,” especially in the case of colonized populations, she risked being refused her humanity in the Victorian feminist imagination. Thus, while Butlerite feminism constructed the humanity of all sex workers—English, French, Indian—precariously, it did so in such a way that non-white sex workers needed to imitate Victorian womanhood more in order to be considered human-rights subjects.