By Yiyun Huang

Edited by Maggie Grether, Felipe Prates Tavares, Michael Zhao, Carolina Melendez Lucas, and Gisela Chung-Halpern

Introduction

… 妇又至,曰:是贼太无情,相与好合许时,无一分顾恋意,忍弃我邪?宜速

反。黄不敢答,但冥心祷天地,默诵经。妇忽长吁曰:此我过也,初不合迷谬,至

逢今日。没前程畜产,何足慕?我独不能别择偶乎?遂去。其怪始绝。1

… The woman came again and said, “You bastard is too heartless! We have been

together happily for so long. How can you bear to abandon me without considering any love [between us]? You’d better go back with me now.” Huang Sheng did not dare to answer, but silently prayed to the heaven and earth and recited Buddhist scriptures. The woman suddenly let out a long sigh and said, "This is my fault. I shouldn't have enticed you at the beginning and led you to the wrong path, which has led to today. A man who has neither official career nor livestock — what is there to admire about you? Can't I find someone else?” Hence, she left. The ghost never came back to Huang Sheng since then.

Chinese folktales on supernatural romance often convey an undertone of admonishment when discussing sexual affairs between humans and ghosts. Yet, beyond warning against desire, this twelfth-century story from Yijian zhi—a compilation of oral folktales collected by contemporary scholar Hong Mai—also reveals alternative perceptions of sexual relationships in the Southern Song society in which it was created and circulated. In her disillusionment with Huang Sheng, the female ghost voices subversive perspectives on emotional investment in sexual encounters and standards of male success. Her final remark also ends the story with an ambiguous moral stance: of the readers who sympathize with the woman for entrusting herself to the wrong person, not all would support her decision to “find someone else.” Playing on the boundary between subversion and entertainment, stories of sexual entanglements can be valuable sources that unveil common people’s experience of and attitudes towards extramarital affairs.

The Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279) is commonly remembered for its military

failures on the northern borders and commercial and cultural prosperity in the southern cities. The year 1127 marked the end of the Northern Song empire as part of the court fled south from the invading Jurchen, moving the capital from Kaifeng to Hangzhou. The humiliation of losing the northern territory and signing peace treaties with the Liao (907-1125) and the Jin (1115-1234) still resonates among Chinese people today. 2 In the shadow of the failure to retake lost territory and frustration against the corrupt court, disillusioned Neo-Confucian scholars envisioned stabilizing the society by emphasizing morality. 3 Meanwhile, moving the political center southward facilitated economic success due to the advanced water transportation system and a climate favorable for agriculture. 4 Commercialization and urbanization saw the growth of cities and a newfound culture of books and entertainment for an unprecedented literati population. 5 As Robert Hymes suggests, the pervasive Neo-Confucian discourse was a reaction against the budding market for cultural and material goods. 6 Yet for most commoners who traveled between cities and their rural homes, life was shaped by the stark contrast between the glamor of urban life and the uncertainty of poverty and banditry in the countryside. In the turbulence caused by frequent warfare, people might have sought a sense of security in the family by embracing conventional family and moral values.

Contemporary historians debate the ways in which Southern Song family and gender dynamics were influenced by social changes and new moral standards such changes produced. On the subject of chastity, for example, Ma Yufeng argues for the rising emphasis on chastity in rural and urban households alike, which is reflected in the numerous retribution stories between dead husbands and unfaithful wives. 7 In contrast, Chen Xueming and Qin Bo suggest that chastity functioned as a means for the educated elite to demonstrate their own virtue, hence affecting elite women more than peasant women. 8 Lower-class women enjoyed a degree of freedom of movement and pursuit of love, but they were not completely free from the influence of the circulating Neo-Confucian discourse and local or familial efforts to regulate their sexuality. Patricia Ebrey observes the double-edged effects of certain social changes for women: commercialization gave women more opportunities to be self-sufficient, but they also became more vulnerable to human trafficking. 9 In comparison to the extensive works on women’s family roles and social status, the study of sexual behaviors unrecorded in orthodox sources has not been given adequate scholarly attention. Beyond their experiences as daughters, wives and mothers, it is important to appreciate the sexual dimension in the lives of women who, like contemporary men, looked for erotic possibilities in books and reality.

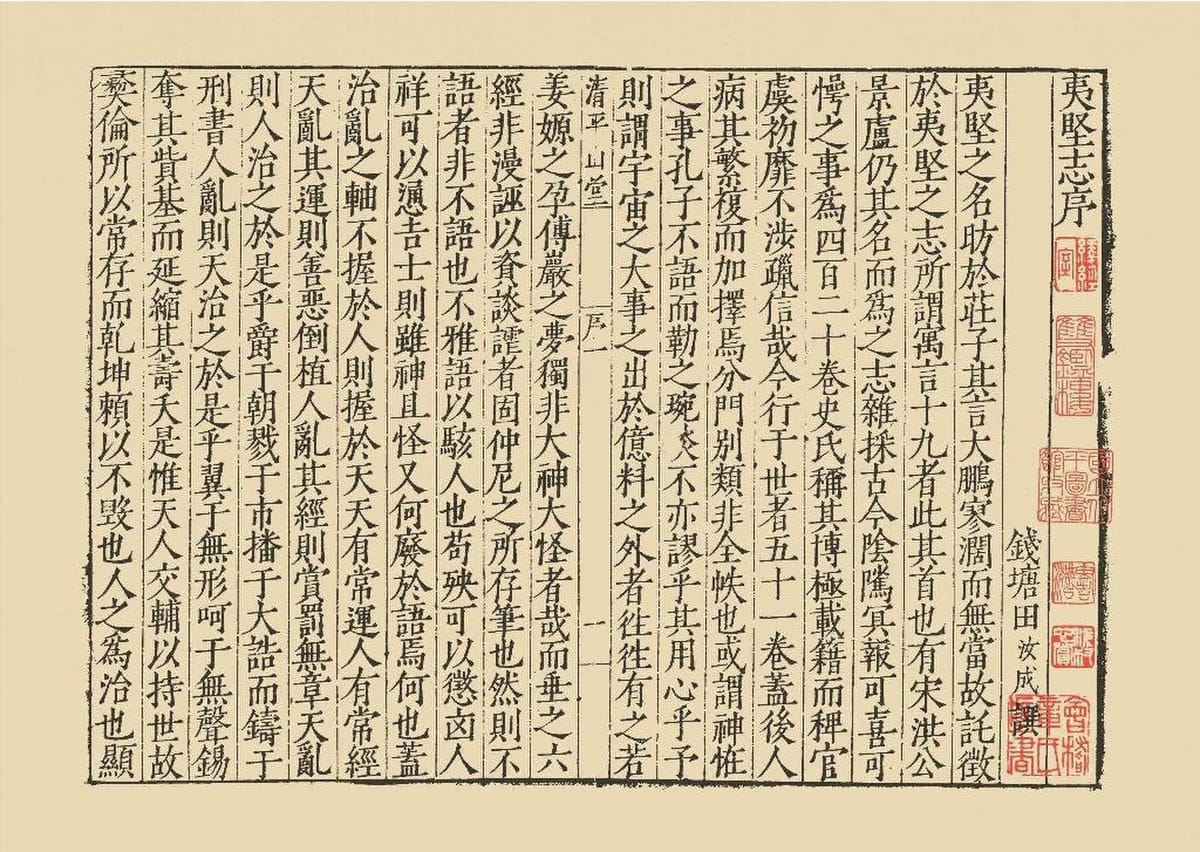

To study the desires of common men and women, one needs to look outside orthodox historical records. Yijian zhi 《夷坚志》(commonly known as “Record of the Listener”) is a collection of contemporary anomalous tales compiled by Hong Mai roughly between 1161 and 1189. Born in a prominent family of scholar-officials, Hong Mai entered the civil service in 1145 and attained a position as high as a Hanlin academician, who served the court and interpreted Confucian classics. Yet, like many, his official career suffered from factional struggles that resulted in demotion to the rural provinces. The experience of travel and political frustration might both have contributed to his later interest in collecting oral folktales from across social boundaries. Published in thirty-two installments over almost forty years, Yijian zhi contains about four hundred chapters (juan 卷) among which less than half survive into today. With the sheer number of anecdotes and the geographical range it covers, the collection is an unparalleled source for the study of the everyday life of common people. Unfortunately, existing gender history studies that employ Yijian zhi as the primary text have generally found the writing more didactic than subversive.

This study intends to read Yijian zhi from a new perspective and reconsider the significance of supernatural elements in selected stories. Yijian zhi belongs to the Chinese literary tradition of zhiguai 志怪 (“accounts of the strange”) popularized in the third century. “Supernatural” can be translated differently to “different” (yi 异), “anomalous” (guai 怪) or “marvelous” (qi 奇). To some extent, both the Chinese and the West perceive the “supernatural” as departures from the natural order, system or cosmography. Yet, the nuanced differences between yi, guai and qi suggest that authors and readers of zhiguai had fluctuating understandings of what characterizes the “strange” and the moral implications behind them. In Southern Song China in particular, the spread of different popular religions and local cults did not produce authoritative texts to control the interpretation of prevailing “strange” incidents—in comparison to medieval England where the Church and the scripture enjoyed considerate power in making sense of the supernatural. The lack of authoritative interpretation contributes to the variety of “strange” entities in zhiguai—ghosts, spirits, immortals, monsters, etc.—and the distinct ways these conceptions challenged social norms.

Through a close reading of stories on sexual entanglements from Yijian zhi, this paper explores different aspects of extramarital affairs in Southern Song society. When possible, the paper references orthodox historical records, which allows one to distinguish between historical practices and cultural attitudes from the “reality” constructed by the text. Starting with an evaluation of Yijian zhi as a historical source, the first section delves into the text’s connection with vernacular culture and its power to shape popular perceptions. This is followed by a discussion of the potential reasons for the recurrence of extramarital affairs. The next section compares the male and female experiences in sexual encounters, highlighting the different fantasies constructed and the varying degrees of power exercised. Finally, the final chapter features study of the consequences of extramarital affairs unveils the nuanced moral and emotional dimensions behind these actions. Through interpreting people’s subjective experiences through the gaze of the wider public, Yijian zhi reveals the complexity of Song commoners’ understanding of morality and desire. As Ebrey theorizes, we can only discover tensions and ambiguities if we “find ways to grasp the cultural whole larger than rationalized ideas in Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism.”

- Historicity, fictionality and orality in Yijian zhi

Before analyzing individual tales, it is helpful to consider some questions regarding Yijian zhi as a historical source. How does one tackle the issue of historicity and fictionality in a fantastic source that claims to be built on factual bases? Is the text a reflection of the historical oral tradition or literary entertainment? By connecting Yijian zhi to the wider vernacular culture, the answers to the above questions shed light on the tales’ power to capture contradictory views and shape contemporary perceptions of sexuality and morality.

In twelfth-century China, the vast majority of the population was illiterate and left few or no written records of its own. Zhiguai is one of the alternative sources that fills the gap with information on common people’s lives. Before the emergence of xiaoshuo 小说 (“minor talk”, close to the modern concept of fiction) in the Song Dynasty, zhiguai was regarded as historical works rather than a literary genre. Although pre-Song readers clearly understood the differences between zhiguai and orthodox historical records, historians should refrain from dismissing the zhiguai tradition as fiction all together. Hong Mai compiled Yijian zhi during a transitory period for zhiguai as a genre. His experience as a historian in the Hanlin academy might also have influenced his methodology in putting together Yijian zhi, further blurring the boundary between historical record and fictional stories. The title of the collection, “Yijian’s Record,” references the ancient philosopher Liezi and suggests that the book is “a record of hearsay.” While it is impossible to determine the fictionality in the accounts provided by the alleged informants, Hong Mai arduously followed a method of oral history, identifying his informants for every tale and revising stories in later installments if he found any mistakes. As Hsiao-wen Cheng points out, it is more appropriate to translate the preface of installment yi (yizhi 乙志)—“皆表表有据依者”—as “all based on traceable informants” rather than “factual sources.” Yijian zhi tales are essentially hearsay told by people who often did not witness the happening of anomalous events. Hong Mai’s written record retains the final shape of the narrative after such hearsay traveled across people.

If historicity in Yijian zhi is understood as historically accurate hearsay, fictionality is best interpreted as the space created by the tales for subversion. Jennifer Fyler proposes that subversive narratives such as stories of women visited by male fox-lovers in zhiguai are made possible only when “an alternative world is safely proposed from the vantage point of fiction.” Zhou Yuhua and Guo Hongying’s study on Yijian zhi also reveals the tales’ tendency to limit free love to ghost lovers, who evade the moral constraints of Neo-Confucianism over the living. These stories retain historicity through their status as written hearsay and conceal fictionality in their more-than-strange content. The liminal status of Yijian zhi enables it to record and reflect social phenomena of the real world, many of which were deemed inappropriate to be included in orthodox sources. Through the fictional contents, historians may catch a glimpse of everyday life and the ways common people understood the society they lived in.

On the question of Yijian zhi as a reliable historical source, Hong Mai takes an ambiguous stance. In the preface of installment yi, he claims, “谓予不信,其往见乌有先生⽽问之 (if one does not believe me, they may go to Mr. Nobody and ask him),” thereby implying that it is impossible to verify the stories. He takes a further step back in the preface of installment zhiding (zhizhiding, 支志丁): “信以传信,疑以传疑......读者曲而畅之,勿以辞害意可也 (Those who believe it should say “it’s true,” those who doubt it should remain skeptical...... Readers should find ways to make the story coherent, without being trapped in the meaning of the words so that they distort the author’s intention)”. Hong Mai’s account indicates the need to treat the stories as “belief tales”—tales not universally accepted but which “concern phenomena that many people believe could be true.” These “belief tales” create a space for imagination and speak into the audience’s fantasies and fears. They capture the multiplicity of attitudes towards real and fantastic phenomena, and thus expose experiences that might have been concealed by orthodox records.

On the other hand, the extent to which Yijian zhi accurately reflects the oral culture in Southern Song society is subject to greater skepticism. Though Hong Mai claimed that his stories came from “poor people, monks living in retreats, retired officials, Daoist priests, blind shamans, ordinary women, lowly clerks, and runners,” B. J. ter Haar’s close study of the informants shows that Hong Mai’s source of information mainly consisted of friends and family, fellow scholars and officials, and the greater kinship and marriage ties (yindang 姻党). Moreover, one of the prefaces reveals the issue of transcribing oral tales. Hong Mai alleged, “盖每闻客语,登辄纪录... 乃亟示其人,必使始末无差戾乃止 (each time I hear a guest’s tale, I write it down... Then I quickly show it to the person who told me the tale, in order to make sure that there are no differences in detail). While Valerie Hansen interprets this practice as a genuine reflection of the folklore, Teiser dismisses it as “widely divorced from oral storytelling” because Hong Mai could not have produced a written version of the conversation between those who could not read. Taking into consideration the difference between the spoken vernacular (baihua 白话) and the written literary language (wenyan 文言), Yijian zhi is unlikely to be a verbatim transcription of Hong Mai’s informants.

However, the educated elite’s contribution to Yijian zhi does not make it a project solely designed by and dedicated to the literati. Ronald Egan maintains that not only did many protagonists of the story belong to the lower class, but the writing also existed outside the traditional literary genres of poetry and prose. The literati’s ambivalent, if not disparaging attitude towards Yijian zhi can be seen in the numerous critiques from contemporaries and later scholars. Despite the distaste of certain literati, the stories possibly circulated in the feasts of educated elites and maintained some elements of oral literature. David Johnson’s study on communication in late imperial China observes that one hidden dimension of elite culture is the role of upper-class women—who generally received less literary education—in instilling non-classical culture into the minds of their husbands and sons. Concubines and servants of the household also served as sources of information outside the literati circle. One can speculate a similar level of female contribution in the Southern Song society, during which marriages between merchants and official families were popular. Yet regardless of the origin of the stories, they only reached Hong Mai when they were told by literati men. It is also likely that Hong Mai deliberately attributed stories to a male informant whose name and identity could be traced—rather than women who originally told the stories—to gain authenticity for his writing. The elements of oral culture in Yijian zhi should not be neglected, but one should also pay attention to the literati’s voice that shaped the narrative choices.

To determine the connection between Yijian zhi, a written text, and oral storytelling, it is helpful to consider the concept of “casual storytelling” proposed by Leo Tak-hung Chan. In contrast to professional storytelling, e.g., shuoshu 说书 (“telling books”), casual storytelling invites the participation of both the teller and the listener and turns stories into meaningful communicative acts that illustrate points or simply generate laughter. In particular, Hymes argues that zhiguai “provided the literati a means to discuss topics unsuitable for formal genres.” In this sense, orality is exercised and amplified by the casual context of storytelling and exchanging ideas, much as Hong Mai described in the preface. More importantly, orality can also be understood in terms of the multivocal nature of Yijian zhi. Cheng identifies multiple agents in the writing of《观音偈》“Guanyin Jie,” in which transmitters add or omit details that eventually make the narrative multilayered and fragmented. Seeing the stories as a whole, the range of messages communicated by different stories also marks the entire collection with multivocality.

Situated between historicity and fictionality, oral and literary genre, Yijian zhi is perhaps best understood in the framework of vernacular culture. According to Glen Dudbridge, “vernacular” is different from “popular” or “folk” because it welcomes the participation of scholars and officials as well as the common people. In Liu Fang’s study of Song urban culture, he highlights the dissolution of fangshi zhidu 坊市制度 (the system that separates markets from living areas in cities) and the rise of private printing shops that created new urban aesthetic tastes. This change makes Johnson’s model of intercommunication between groups with varied literacy suitable for Southern Song society. As social groups intermingled, people who could and could not read might have lived closely, enjoyed similar entertainments, and exchanged beliefs and values. Hoping to publish books to attract diverse audience groups in the city, the flourishing printing shops also paid close attention to the conversation between their customers. As a product of intercommunication, Yijian zhi could reflect ideas discussed by elites and commoners alike. Furthermore, Hong Mai only decided to continue his work after the first printed installment became immensely popular. The audience’s curiosity for strange stories that mirrors the world they live in but challenges norms clearly influenced the choice of tales collected in each installment. During the forty-year period of publication, the thirty-two installments closely followed contemporary tastes and became a source of influence over people’s beliefs and attitudes.

As historically accurate hearsay, Yijian zhi recorded fantastic events that gave those who told and read the stories a space to express hidden opinions and desires. Although the original oral tales were transcribed into the literary language, a sense of multivocality was retained by the varying beliefs Yijian zhi transmitted across class boundaries. Mirroring and influencing contemporary perceptions, Yijian zhi provides an entry point for grasping the often-contradictory moral codes and practices regarding extramarital affairs in Southern Song society.

- Contextualizing Extramarital Affairs in Southern Song Society

Besides a few words of admonition, prescriptive sources such as classical texts for female education tend to avoid discussing stigmatized practices like extramarital affairs. The private and taboo nature of extramarital affairs also meant that many cases stayed inside the family, without leaving traces in legal records. It is impossible to gather a clear picture of the sex lives of people from the lower-class. However, investigating the social changes that might have encouraged people to be involved in such relationships can provide insight into the society Yijian zhi reflects.

Increased movement of people between cities and villages could have been the major factor contributing to the increased frequency of extramarital affairs. As commercialization made interregional communication possible, people of all classes traveled more frequently, spending much more time outside the family and seeking opportunities for sexual encounters. Officials went on work trips; the literati organized outings with fellows and courtesans; merchants traveled on land and water routes for trades; students from the peripheries visited the capital for the imperial examination. Even poor farmers would have been no strangers to movement. As the Song government lifted restrictions on the private ownership of land, farmers in poverty often sold their land and became tenant farmers who moved from place to place. Despite the increased number of people in movement, traveling remained risky due to the constant social unrest. In Yjian zhi tale《刘子昂》“Liu Ziyang” (32), the official Liu Zi’ang traveled to Hezhou without his family because “方淮上乱定,独身入官 (the upheaval in the Huai River region was just quelled, [so he] took his office alone).” Trips could take weeks and months, during which married men were not always accompanied by their wives. In both《王彦太家》 “Wang Yantai Jia” (2) and 《张四妻》 “Zhang Si Qi” (3), monsters took advantage of the husband’s long-term absence to enter the household and assault the wife. Wang Yantai was a wealthy merchant while Zhang Si was a porter. Their experiences reflect a shared anxiety about the sexual insecurity of the wife left behind, regardless of social status.

As for the male travelers in Yijian zhi stories, they seemed to develop a common practice of starting a causal relationship at the place they stayed and ending it when they left. This is especially true for the scholars visiting the capital for the imperial examination. The sexual encounters on the road might have relieved the pressure of exams and the hardship of travel. When the scholar Huang Yin decided to leave the hostel for the examination, he did not bother to bid farewell to the woman he had been sleeping with for the past half a month. He said nothing and offered her five taels of silver. Huang Yin’s lack of compunction towards the woman suggests that such casual relationships were normalized among the scholars and afforded women some economic benefit.

Wives who understood their husbands’ susceptibility to sexual temptations on the road might have experienced the anxiety of infidelity. While extramarital affairs could be tolerated if the husband returned home, legal records contain several cases of desertion. Presumably, a number of the men started a new family elsewhere. Southern Song law stipulated that if the husband left for more than three years without returning, the marriage was dissolved and the woman was free to remarry. The need to establish an ordinance to approve remarriage after the long-time absence of the husband suggests such situations were common. While the Song government could not control how long marriages lasted, it could encourage the formation of new families in order to maintain social order and replenish the war-stricken population. The narrator’s anxiety towards the breakdown of family order due to travel is also reflected in stories such as 《陶彖子》“Tao Tuan Zi” (5), 《星宫金钥》 “Xinggong Jinyao” (6) and 《石六山美女》 “Shiliushan Meinü” (7), in which the female spirit/immortal attempts to snatch the man from his household to live in an otherworld. These stories often conclude with the female supernatural being advising the man to return to his family, thereby making a didactic statement against desertion. Such endings prevent the stories from being overtly subversive, so the audience can safely enjoy the protagonist’s temporary departure from family responsibilities.

Turning to female travelers, historians Tie Aihua and Zeng Weigang’s work surveys stories concerning erotic encounters between humans and ghosts and concludes that women of all classes traveled for various socially acceptable reasons. Building on their findings, this chapter draws attention to the conventional exchange between the spirit-disguised female traveler and the enticed man. In a typical encounter, the woman gives a reason for her solo appearance, followed by the man offering her a place to stay. The woman's reason for being alone does not always stand up to scrutiny. In 《京师异妇人》“Jingshi Yi Furen” (8), the woman alleges that she came to the lantern festival with her friends but became separated from them, so she decides to go with the scholar to avoid the danger of being abducted. Later she becomes a concubine of the scholar, who does not question why her family did not search for her during her six-month absence. The fact that the man is comfortable living with a woman of unknown origin implies that he possibly perceived her as a private prostitute (siji 私妓) who evaded governmental records and traveled solo. The narrative conceals the woman’s identity as a prostitute and the man’s real motive to offer her a place to stay, which suggests that the story might have been told from the man’s perspective. To skirt the ambiguous moral and legal liability in entering relationships with these women, men often claimed that they bought the woman as a servant or concubine, which then legalized the action.

Illicit sexual affairs happened inside the household, too. Under the spread of local cults and popular regions, it was common for traveling monks and Daoist priests to visit homes in the name of religious practices and sleep with the mistress. 《妙净道姑》“Miaojing Daogu” (9) describes a man who disguised himself as a female Daoist priest to enter people’s houses and seduce their wives. The bluntest commentary on the phenomenon comes from 《方氏女》“Fangshi Nü” (11), in which the possessed girl mocks the Daoist priest, “汝与某家妇人往来. 道行如此, 安得敢治我 (You are having an affair with somebody’s wife. This is your diaoheng (the correct way and practice). How dare you find yourself qualified to punish me)?” Besides criticizing the immoral behaviors of monks and Daoist priests, these stories illustrate the possibility of sexual encounters inside the supposedly safeguarded home, which added to men’s insecurity about their wives’ sexuality.

Another noteworthy social change at this time was the expanding market for concubines and prostitutes, a result of the growth of the educated class and the legalization of prostitution. Many poor peasants sold their daughters to pay taxes or debts, which made it more difficult for men of lower classes to find spouses. Du Bing also points out that, despite the law stipulating that only men who remain childless over forty could take concubines, many took concubines at a much earlier age. For widows, remarriage was not compulsory, because their increasing involvement in production allowed them to be self-sufficient. Therefore, it is likely that single men and widowers from lower classes encountered some challenge in finding a wife. Men who did not marry might have sought casual physical relationships as an alternative. This is certainly the circumstance reflected in Yijian zhi, in which the craving for a spouse drives many into a sexual relationship with a spirit or monster. In 《茶仆崔三》“Chapu Cui San” (13) and 《管秀才家》“Guan Xiucai Jia” (12), both protagonists choose to continue the relationship after knowing that the woman they had been sleeping with is a monster. They suspect that they will never get another chance to be with a beautiful woman in their state of servitude. In 《郑四妻子》“Zheng Si Qizi” (14), the sixty-year-old goatherd Zheng Si does not divorce his wife, even though she did not bear any children and was having an affair, possibly out of the understanding that it would be extremely difficult to remarry. For those who could not afford to marry, remarry or buy concubines, a causal relationship appears to have been the practical solution to sexual needs.

One should not forget that extramarital relationships remained stigmatized and adultery was punishable by two years of penal servitude. Yet surviving legal records hint that officials preferred not to handle these cases and often gave lenient or no punishments. Officials probably adopted a neglectful attitude to avoid extra work caused by the recurrence of extramarital affairs. Certain scholar-officials did share an interest in regulating family practices and establishing models for emulation among the commoners. For instance, the renowned Neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi expressed his discontent about the peasants of Tongan who completely disregarded orthodox marriage rites. In reality, efforts from the local literati to control illicit sexual activities might have only received limited results. In 《游节妇》“You Jiefu” (15), the local magistrate Dai is impressed by the fact that “闾阎匹妇而能守义保身 (a peasant woman can protect her chastity)” and rewards the peasant woman You the title of “节妇” (jiefu, a chaste woman/wife). Although Dai is described as “不能察 (lacking discernment)” and falsely sentences Ning Liu (brother of You’s husband) to death based on You’s fabricated charge of sexual assault, his handling of the case still reflects the contemporary attitude of extolling exceptional chastity and ignoring conventional licentiousness.

This acquiescent attitude towards extramarital relationships is a product of the social changes that influenced the behaviors of people in Yijian zhi and the wider Southern Song society. Travel and mobility impacted both men and women: they were simultaneously drawn to the excitement of sexual adventures and troubled by their partner’s uncontrolled sexuality in their absence. The contrast between the admonition from prescriptive sources and the pervasiveness of the practice reveals the ambiguous moral implications and uncertain legal consequences of extramarital affairs. As stories construct fantasies about suppressed desire, they reflect and work through real-life anxieties.

- Comparing female and male perspectives in sexual encounters

Besides the social reasons that contributed to the recurrence of extramarital relationships, as examined in the previous section, stories in Yijian zhi show that men and women carried different grievances and entered sexual entanglements with different motivations. An investigation into how sexual encounters were initiated and how “consent” was negotiated gives historians a glimpse into the construction of masculinity and femininity in the Song society.

In several stories involving a female spirit and a mortal man, one observes that it is often the man who attempts wooing first. In 《小陈留旅舍女》“Xiaochenliu Lüshe Nü” (4), the scholar Huang Yin offers the statue-turned-girl wine and flirts with her: “微言挑谑,略不羞避,遂就寝 ([he] tantalized [her] with words, yet [she] was not shy, thus [they] went to bed)”. A more revealing case can be found in 《胡氏子》“Hushi Zi” (17), in which the single young man makes an offering every day to the allegedly stunning woman buried behind a shrine, hoping to meet her one day. A reflection of the sexual repression of single men who turned to the otherworld as an outlet, these stories also demonstrate that seduction and courtship from men were normalized and did not harm one’s reputation. In fact, it seems more common to assign the blame for illicit affairs to the female party. Such is the case in 《丘鼎入冥》“Qiu Ding Ruming” (18): although the story does not specify who started the affair, the official of the underworld court assumes that the woman seduces the man Qiu Ding, an act that compromised her integrity and made her unworthy to reincarnate into a man.

Stories of female supernatural beings seducing men may alternatively reflect the contemporary understanding of sexual attraction and desired masculinity. As Tie and Zeng point out in their research, scholars and merchants make up the main social groups that encountered enticing spirits in Yijian zhi. This can be attributed to their physical mobility, but scholars in particular were also associated with sexual attraction. In 《小陈留旅舍女》“Xiaochenliu Lüshe Nü” (4), the spirit girl knocks on Huang Yin’s door and said, “少好文笔,颇知书。所恨堕于女流,父母只令习针缕之工,不遂志愿......闻君读书声,欢喜无限,能许我从容乎 ([I] was interested in writing and books since [my] youth. Unfortunately, [I] was born a woman and against [my] wish, [my] parents asked [me] to study weaving only... Hearing you reciting books makes me incredibly happy, could I stay)?” For women who emulated literati practices, the scholarly achievements of traveling students like Huang Yin were particularly attractive. A similar understanding can be seen in 《蔡五十三姐》“Cai Wushisan Jie” (20), where the runaway girl finds the “xiucai” (title of scholar who passed the entry-level imperial examination) Li Sheng suitable as her future husband. Li Sheng was a runway student and certainly did not pass the exam to earn the title of “xiucai,” but his scholarly vestments might have misled the girl into thinking that he had hopes for an official career. As the imperial examination system reached maturity during the Song dynasty, more commoners had the chance to move up the social ladder by becoming officials. The female spirits’ affinity for scholars reveals women’s desire for the social mobility accessed by marrying an aspiring student and the form of ideal masculinity embodied by hard-working students.

In comparison, stories with reversed genders disclose women’s longings and discontents in their married life. Just as stories concerning enticed men often depict the youthfulness and beauty of the female spirit, enticed women were equally attracted by appearance. The admiration of looks is evident in both 《永康倡女》“Yongkang Changnü” (21) and 《苦竹郎君》“Kuzhu Langjun” (22), where the captivating look of the clay idol or statue renders the woman motionless in adoration. The fact that appearance was not the most important factor in arranging a marriage probably left many dissatisfied with their spouse’s looks. One may assume that incidents like Cai Wu running away from his wife because she looks nothing like the matchmaker described were not uncommon. For unhappily married men and women, stories of humans receiving the favor of a supernatural beauty—whose looks were depicted in vivid detail—provide them an opportunity to escape from reality and exercise their erotic imagination.

Enticed men received little criticism, but enticed women were usually associated with 淫 yin: the inappropriate and excessive desire of a licentious person (usually a woman). The story “Kuzhu Langjun,” for example, describes the enticed woman as “淫冶 (licentious and seductive).” Women were expected to hide their sexuality, and the Song people often explained acts of deviation as spirit possession—possibly to protect the reputation of the woman and her family. In “Fangshi Nü” (11), the allegedly possessed woman “盛饰插花就枕... 必酒色著面.喜气津津然 (decorated her head full of flowers before sleeping... [and woke up] with wine on her breath and a joyful face)” The unusual display of sexual attraction and emotion reveals the suppressed desire made visible by the male spirit’s possession. Additionally, certain stories emphasize the sexual prowess of the monsters that seduced or possessed women. 《江南木客》“Jiangnan Muke” (23) notes that spirits and monsters not only altered their appearance according to what people found attractive, but also had “阳道壮伟 (strong and magnificent penises)” Such a description speaks into the fantasies of women suffering from sexual dissatisfaction, while mirroring the sexual insecurity of their husbands.

Women’s dissatisfaction with marriage extends to the grievance against an incompetent husband. In 《五郎君》“Wu Langjun” (24), Zheng, renowned for her beauty, marries the poor and haggard Liu Yang who can not make a living and drinks with his friends all day, leaving her “饥寒寂寞 ([suffering from] hunger, cold and loneliness)”. It is only after Zheng is possessed by a spirit that she completely changes her attitude and finds every chance to humiliate Liu Yang. Similarly, in《程山人女》“Cheng Shanren Nü” (25), Cheng, who is enticed by a snake, mocks her husband, “此是好士大夫,爱怜我...... 岂汝贱愚工匠之比 ([The snake] is a good man who loves and takes care of me... How could a poor and foolish craftsman like you compare [to him])?” Zheng and Cheng’s dissatisfaction with their husbands’ neglect and failure to provide material wealth, reflect married women’s unmet expectations. Cheng’s words suggest that unequal intellectual sophistication also presented an issue. Cheng, the daughter of a shanren (scholar-recluse), received some education and finds the snake disguised as a scholar more attractive than her craftsman husband of limited scholarly attainment. Through voicing their grievances with their husbands and pursuing more attractive lovers in the otherworld, wives in these stories offered an outlet to real women dissatisfied with married life.

Unfortunately, discontented wives in the real Song society did not have the range of options enjoyed by women in Yijian zhi. Even within Yijian zhi, female agency is limited. The story leaves no words on whether Liu Yang’s wife wishes to live with the spirit. In reality, the desires of women sold as wives were probably disregarded. Women entering rich households as concubines were also subject to violence from the husband and the mistress, illustrated by various Yijian zhi tales on jealous wives beating concubines to death. In another case, “Lang Yan Qi” (1), the ghost of Lang Yan’s wife abandons Huang Sheng because she sees no future for him in the official career or abundance of property. Yet many women who held grievances towards their husbands could not walk away like Lang Yan’s wife or initiate a divorce on the grounds of their husband’s incompetence. Although one should not completely dismiss their subversive potential, stories containing dissident voices may be better considered an imaginative escape from the disappointing reality of married life rather than a reflection of women challenging the established conducts.

Considering the negotiation of “consent” further reveals the imbalance of power between men and women in sexual encounters. Although few resisted the temptation, men in stories generally had the power to reject the invitation from female spirits. In 《梦女属对》“Mengnü Shudui” (26), the female ghost fails to seduce the scholar to sleep with her, because he is too absorbed in exam preparation to pick up the erotic connotation of her words. In 《陈舜民》 “Chen Shunmin” (27), when Chen Shunmin recites scriptures to repel the female ghost, she replies angrily, “何必如此 (why do you have to take it to this end)?” The female ghost is not offended by Chen’s rejection, but by the hostile way he reacts, which implies that she does not plan to coerce him. In contrast, when women attempt to reject the approach of men, the human or supernatural man often assaults them violently, as seen in the stories “Shiliushan Meinü” (7) and “Wang Yantai Jia” (2). In cases like “Fangshi Nü” (11), where the story omits how the male spirit approached the woman and starts off straight with the abnormal acts caused by spirit possession, one sees a more limited agency exercised by the woman. As many scholars point out, the tendency is to emphasize women as the passive object rather than the subject of desire.

Yet, Yijian zhi still recorded instances of women actively expressing their desire and attempting to coerce men into physical relations. In 《张三店女子》“Zhang San Dian Nüzi” (28), the fox-disguised woman threatens to accuse Li Qi of abducting her if he doesn’t take her in. However, such threats might only intimidate those at the bottom of the social hierarchy, who had neither power nor money to influence the judgment of the local court. In comparison, women were much more susceptible to slander, an alternative form of violence. In 《王武功妻》“Wang Wugong Qi” (29), the Daoist priest frames the wife for adultery, causing her husband to abandon her and giving the priest the opportunity to snatch her from the house. Whether human or supernatural, women had significantly less agency and power to coerce men into a sexual relation and to reject men’s approaches.

Stories in Yijian zhi also demonstrate that the economic exchange became a prominent incentive for sex. In “Zhang Si Qi” (3), the wife in the story goes to bed with the ghost after he gives her several taels of silver. In contrast, instead of using economic benefits to lure men into sexual entanglements, female spirits appeared to give out money only to subsidize the man in financial difficulty, as demonstrated in “Lang Yan Qi” (1) and “Chapu Cui San” (13). Given the obvious association with prostitution and obtaining money from sexual encounters, such stories explain the economic gains as women’s generous help to financially struggling men, thereby avoiding posing an explicit challenge to the gender order. This also explains the statue-turned-girl’s “flushed, as if it’s a guilty look” after she receives five taels of silver from Huang Yin. She is humiliated by the fact that Huang Yin interprets their relationship as an economic rather than romantic exchange. The financial gains brought by extramarital affairs often led to the husband and the family’s tolerance of the relationship. After Liu Yang’s wife confesses her affair to him, he is said to be “意虽愤愤,然久困于穷,冀以小康,亦不之责 (angry, but [he] was impoverished for too long and hoped to be moderately well-off, so he did not blame [his wife].” The parents in 《雍氏女》 “Youngshi Nü” (30) also tolerate their daughters’ relationship with the immortal because he can make pearls appear from the rice which quickly gives them enough money to build manors. For poor commoners, economic benefits significantly outweighed the concern for their wives or daughters’ chastity and the judgments from the community.

Comparing male and female perspectives on sexual encounters in Yijian zhi illustrates how men and women expressed their discontent and constructed their fantasies in tales differently. Each tale describes an anomalous event but speaks to shared sentiments on unsatisfactory marriages and suppressed desires. The difference between female and male experiences in sexual encounters also demonstrates that women exercised a significantly limited agency in entering and rejecting a relationship. The role of money further complicates the nature of consent and the relationship. Beyond a binary divide between romantic or economic exchanges, extramarital affairs reveal tensions in the contemporary moral codes which Yijian zhi did not attempt to resolve and invited its audience to make their judgment.

- Consequences of and attitudes towards extramarital affairs

Most stories on sexual encounters in Yijian zhi share a similar ending: the parties separate and the seduced person dies or returns to normal life. While such endings point to a general discouraging attitude towards illicit affairs, individual stories contain different voices that reveal contemporaries' emotional responses and moral concerns towards extramarital relationships. The narrative thus constitutes a psychological space in which people confront and attempt to solve contradictions.

In stories where extramarital affairs end peacefully, characters demonstrate an understanding of the relationship’s temporary nature. For instance, although details were omitted, it is reasonable to assume that interactions between Qiu Ding and the woman begin and end naturally: “...乃少年日与此女杂居,朝夕往来,因与之合,后嫁某氏子 (when [Qiu Ding] was young, they lived closely and saw each other every day, so they slept together, later [she] married someone’s son…”). Most stories attribute the separation to the exhaustion of 缘分 (yuanfen, fateful coincidence)––the force that determines the destined affinity between two people. This concept implies that how the affair develops is out of human control and that ending the affair complies with the natural order. Such is the attitude adopted by the woman in 《西湖女子》“Xihu Nüzi” (16), who recommends the official takes a medicine mentioned in Yijian zhi––a skillful authorial move to show the popularity and reliability of the text––to expel the 阴气 (yinqi, yin energy) from his body. In doing so, she not only expresses concern for the official before leaving him, but also makes the supernatural romance a transient episode that will not disturb the rest of his life.

Nevertheless, many tales depict parting scenes with tears and regrets, demonstrating emotional investment in extramarital relationships. Before the supernatural being leaves, they often express their wistfulness towards separation. As the willow spirit in “Tao Tuan Zi” (5) puts it, “久与子游,情不能遽舍,愿一举觞为别 ([I] have been with your son for a long time and have deep feelings that [I] cannot let go at once. [I] wish to have a drink [with him] as parting).” Sometimes the depiction is more subtle: when Qian Yan confesses to his lover that he knows she is a snake, she “默默不语 (remained in silence and could not speak a word).” The silence allows readers to imagine the complexity of emotions the female spirit might have experienced after her identity is revealed. Similarly, not all humans moved on easily from their encounters with supernatural beings. Years after, the official in “Xihu Nüzi” (16) still speaks of the woman with “凄怅” (sorrow and frustration). As for the girl in “Yongshi Nü” (30) who remains unmarried after the male immortal left, “每忆畴昔少年之乐,至潸然陨涕 (whenever [she] recalled the happiness of her youth, [she] shed tears)”. In the most extreme case, after his parents destroy the statue that has been turning into a girl and enticing him for the past few months, Wang Fu dies in grief. While the story does not praise or criticize Wang Fu’s unusual reaction of dying for love, the intense emotional appeal certainly reflects the importance of emotional investment in sexual encounters.

Casual sexual encounters could also develop into long-term relationships which involved different commitment expectations and moral consequences of breaking the “contract” (yue, 约) people made to each other when they started cohabitation. In 《崔春娘》“Cui Chunniang” (31), Zhang Lin passes the examination and plans to marry a rich widow instead of Cui Chunniang. Cui accuses Zhang of breaking their vow before the temple god and he later dies in regret and fear. Cui Chunniang perceives her relationship with Zhang Lin as marriage both because of the alternative (but unofficial) marriage contract she forms by vowing to the god, and because “居数年,尝宿其家 (for years, [Zhang Lin] often stayed at her house).” The understanding that long-term cohabitation between a man and a woman makes them unofficially husband and wife is also reflected in “Liu Zi’ang” (32), as the female ghost reminds Liu Zi’ang that they “相待如夫妇 (treat each other like husband and wife)”. Cui San’s description of “义均伉俪 (the sentiments [we have for each other] equals those of a married couple)” also demonstrates his perception of his relationship with the fox spirit. The implication is that people lived together like a married couple and thus held some moral and legal responsibilities towards each other. This may explain why both men are reluctant to listen to suggestions to break off with the female spirit, which they consider an act that violates the unofficial marriage contract.

The role of Daoist priests and monks in sabotaging the relationship deserves special attention. In the stories examined, Daoist priests and monks tend to be blamed for disturbing the family order. This reflects real-life discontent with traveling Daoist priests and monks who entered homes to seduce women and/or frame them as supernatural beings to extract money. This is the belief held by Cai Wu: he curses the monk who warns him of his wife’s dubious identity for “欲诱化吾妇 (trying to seduce my wife).” His ghost-turned-wife replies, “我与尔作夫妇岁馀,今已怀妊,白地撰此恶语 (We have been husband and wife for years now and I am pregnant. How could [he] fabricate these malicious words out of the blue)? One interpretation in Zhou and Guo’s study is that Daoist priests and monks represent the intervention of Neo-Confucianism that seeks to admonish the reader about the immorality of living with women of unknown origins. On one hand, introducing an outsider who insists on expelling the harmful spirit removes some of the moral condemnation one would receive from abandoning their partner. On the other hand, it exposes the susceptible nature of the man in the story: he is easily influenced by a stranger and does not feel guilty about leaving the woman who was like a wife to him. The Daoist priest or monk’s intrusion thus makes a morally ambiguous comment on the man’s decision to end a long-term affair.

Yet besides moral condemnation, men who abandoned their human or ghostly lover do not always receive karmic retribution. This indicates that abandonment was considered less serious moral misconduct compared to, for example, being extremely unfilial or bloodthirsty. At the end of “Cai Wushisan Jie” (20) and “Qian Yan Shusheng” (36), both enticed men return to their normal lives after the spirit is expelled. In cases where the man suffered or died, the narrative tends to attribute it to the inherent negative influence of yin energy from sexual entanglement with a ghost. Impaired health thus serves as a warning against excessive desire rather than abandonment. However, there are examples of active retribution from the abandoned women, such as the fox spirit in “Zhang San Dian Nüzi” (28) who retaliates against Li Qi’s attempt to leave her by depriving him of his spirit and appetite. Though the story ultimately aims to illustrate the female spirit’s terrible retribution, it presents a possibility of reversing the gender dynamic, where the woman overpowers the man and forces him to stay in the relationship.

Another unusual form of retribution is infanticide, of which the most representative example is《岛上妇人》“Daoshang Furen” (35). In the story, a shipwrecked merchant is stranded on an island, where he meets a woman who takes him in and has three children with him. Seven or eight years later, after seeing the merchant getting on a ship to leave the island, the woman tears apart the three children before him. Yet, compared to the woman’s extreme grief and rage that causes her to “扑地,气几绝 (fall onto the ground and almost stop breathing),” the man only makes a gesture of apology and sheds tears. He does not appear to be unduly distressed by the death of his children. The difference in the importance of children to the man and woman raises the question of how children produced outside marriage were perceived, on which Yijian zhi provides different interpretations. In “Cai Wushisan Jie” (20), after the ghost mother is expelled by the Daoist priest, the children stay with their father, though readers do not know whether they were discriminated against in the family and community. However, the female spirit in “Qian Yan Shusheng” (36) takes away the child after Qian Yan discovers her identity. He makes no attempt to retain them.《鼎州兵妻》“Dingzhou Bingqi” (37) contains a particularly disturbing description of the unfaithful wife being beheaded, leaving the infant – though unspecified, who could be fathered by another man– sucking milk from the breast of the headless body.

While these stories reveal the dispute over children produced outside marriage, they convey a general lack of concern and love for them. This indifference seems to contradict the idea of jen’ching (universal human feelings) promoted by the Song literati. The idea reached the wider public through visual mediums such as the fan painting “Knick Knack Peddler,” in which the peddler, a stranger, rushes to aid the children in danger of being bitten by a snake. Love for children became a popular subject in high and folk arts alike, but it is unclear whether such sentiments extended to children born out of wedlock. The treatment such children received in the Southern Song society is a topic worth further investigation. The evidence examined so far only suggests that the lack of legal connection between the spouses and between parents and children resulted in a weak sense of responsibility and emotional tie—something Hong Mai might intend to criticize, or at least give attention to, by including a few words on the children’s tragic endings.

More scholars have studied the consequences for women who were passively possessed by spirits or who actively pursued sexual encounters outside marriage. In short, such women were susceptible to greater bodily damage, but generally met no difficulty in returning to the marriage or getting married later, a dynamic which again reflects the disregard for chastity among peasants. Instead, this study explores the boundary that determines whether extramarital sex was tolerated or punished. As Section 2 discussed earlier, men from the lower class often tolerated their wives’ infidelity. The reason given by Zheng Si was “畏邻里耻笑 (the fear of mockery from neighbors)”. Similarly, Ning Liu was said to “每侧目唾骂,无如之何 (every time slanted his eyes and cursed [the unfaithful wife of his brother], but there was nothing he could do)”. It is not until Zheng Si hangs himself to escape mistreatment from his wife, and Ning Liu is accused of the false charge made by his brother’s wife, You, that village members send the adulterous wives to the local authority in rage. If kept in a private or semi-private sphere, adultery was more acceptable than the public abuse of the head of the family. Even if the affair reached the public’s ears, the local community seemed to be amused rather than appalled by such incidents. As 《郑二杀子》“Zheng Er Shazi” (10) illustrates, extramarital affairs could become a neighborhood joke that generated laughter from the crowd and embarrassed the couple on public occasions like one’s wedding feast. Many lower-class men tolerated their unfaithful wives out of fear of gossiping and mockery from the local community, but the community could simultaneously provide them the power to punish adultery. The fact that Zheng Si only dares to intimidate his wife after his death when she is in prison, demonstrates a subtle power dynamic between the husband and wife in the rural village that could be altered by the community’s involvement.

Ending an extramarital relationship had different consequences for the men and women involved. The temporary nature of such relationships made the separation an intense emotional experience. The emphasis on honoring marriage contracts made outside legal procedures was undermined by the inconsistency in the retribution for abandonment. The protagonists in the stories also undertook the punishments for the unfaithful differently. The contradictions in these stories reflect the mixed contemporary attitudes toward illicit affairs, encouraging the audience to affirm or challenge their established beliefs.

Conclusion

The story “Dingzhou Bingqi” (37) concludes, “盖此妇当诛,故委曲如是,使周祐先半日死,则妇幸免矣 (This woman was destined to be killed, which is why things were so convoluted. If Zhou You had died half a day earlier, then this woman would have been spared)!” It is unclear whether this is a comment from the compiler Hong Mai or the transmitter of the story, though the choice to include it suggests an ambiguous, if not dissident moral stance taken by the narrator. Hong Mai rarely expressed his own opinion or made any explicitly didactic remarks, but occasional comments like this encouraged the reader to find pleasure in the ambiguity of the moral message. The contradictions within individual stories and between messages conveyed by different stories make Yijian zhi a multivocal text that captured the opinions of various social groups and spoke to an audience with diverse beliefs. The text is thus a valuable mirror of Southern Song society’s vernacular culture, which welcomed the participation of people across class boundaries and literacy levels.

Yijian zhi also gives historians insight into the private lives of people whose activities and beliefs were rarely covered in orthodox records of Neo-Confucian scholars, such as people who engaged in extramarital affairs. The increased movement of people might have contributed to the commonality of casual sexual encounters, which then fed into the anxieties and sexual fantasies of men and women at the time. The tales in Yijian zhi served as a psychological space in which people exercised their imagination to channel discontent and express unfulfilled desires in reality. As men and women voiced their grievances and constructed their fantasies, one sees the expectations of male and female expression (or suppression) of sexuality, as well as the ways people responded to them. The stories also covered a range of attitudes toward and consequences of extramarital affairs, encouraging the reader to negotiate contradictions between ethics and desire. The range of ideas represented in the collection situate contemporary behaviors and perceptions within a vibrant culture of storytelling and entertainment.

Yijian zhi seldom falls into the didactic mode, instead embracing moral ambiguity. Reflecting a society where legal codes and public opinion produced inconsistent attitudes toward sexuality, stories about sexual entanglements in Yijian zhi show how contemporary people expressed and suppressed desire in varied ways. This world of humans and ghosts situated between reality and fiction became a space to defend or challenge ideas of deviancy, leaving questions instead of answers and mirroring readers’ own ambiguous moral codes. Within this unresolved tension, one can glimpse the diverse living experiences of the common people of the Southern Song society.

[1] 《郎岩妻》“Lang Yan Qi” (1), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》[Yijian zhi], ed. J. He (Beijing, 1981), p. 701. A table of numbered English synopses of the selected stories is attached in the appendix.

[2] J. Chaffee, ‘Introduction: Reflections on the Sung’, in J. Chaffee and D. Twitchett (eds), The Cambridge History of China (15 vols, Cambridge, 2015), v, p. 2.

[3] P. Ebrey, The Inner Quarters: Marriage and the Lives of Chinese Women in the Sung Period (Berkeley, 1993), p. 4.

[4] H. Cheng, ‘Traveling Stories and Untold Desires: Female Sexuality in Song China, 10th-13th Centuries’ (Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington, 2012), p. 2.

[5] F. Liu, 《盛世繁华:宋代江南城市文化的繁荣与变迁》[Prosperous times: the prosperity and changes of urban culture in Jiangnan during the Song Dynasty] (Hangzhou, 2011), pp. 52, 372.

[6] Chaffee, ‘Introduction: Reflections on the Sung’, v, p. 7.

[7] Y. Ma, 《论 <夷坚志>中的女性形象及其妇女观》[On the Image and View of Women in Yijian zhi], 高等函授学报(哲学社会科学版), 27/12 (2012), p. 56.

[8] X. Chen and B. Qin, 《经与权:中国传统女性观与妇女生活的变迁》[Classics and Power: changes within the Chinese traditional view of women and women’s lives] (Sichuan, 2015), p. 42.

[9] P. Ebrey, ‘Engendering Song History’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 24/1 (1994), pp. 341-2.

[10] S. Xu,《宋代妇女史研究述评》[A Review on the Research of Women’s History in Song Dynasty], 浙江理工大学学报 (社会科学版), 40/5 (2018), p. 493.

[11] Ebrey, ‘Engendering Song History’, p. 342.

[12] V. Hansen, Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127-1276 (Princeton, 1990), pp. 17-8.

[13] See, for example, D. Bo, 《〈夷坚志〉婚恋小说分析》[An Analysis of Marriage and Love Stories in Yijian zhi] (2009); Y. Ma., 《论 <夷坚志>中的女性形象及其妇女观》[On the Image and View of Women in Yijian zhi] (2012); X. Yan, 《从〈夷坚志〉看宋代婚姻》[A Research of Song Dynasty Marriage in Yijian zhi] (2016).

[14] J. Zeitlin, Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale (Stanford, 1993), p. 5.

[15] See Durkheim’s definition of “supernatural” in B. Saler, ‘Supernatural as a Western Category’, Ethos, 5/1 (1977), pp. 34-5, and Campany’s definition of anomaly accounts in R. F. Campany, Strange Writing: Anomaly Accounts in Early Medieval China (Albany, 1996), pp. 3, 12.

[16] C. S. Watkins, History and the Supernatural in Medieval England (Cambridge, 2007), pp. 23-4.

[17] K. Minoru, ‘New developments in the study of Chinese fiction—Theoretical issues and a discussion of the application of the colloquial story (xiaoshuo/小说) to the study of social history’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 35/1 (2005), p. 140.

[18] Ebrey, ‘Engendering Song History’, pp. 342-3.

[19] Z. Zhang, Hidden and Visible Realms: Early Medieval Chinese Tales of the Supernatural and the Fantastic (New York, 2018), p. xxviii.

[20] S. M. Allen and J. W. Chen, ‘Fictionality in Early and Medieval China’, New Literary History, 51/1 (2020), p. 233.

[21] Hansen, Changing Gods, p. 18-9.

[22] R. Egan, 《洪迈<夷坚志>中宋代妇女处境之探讨》[Exploring the Lives of Song Dynasty Women through Hong Mai’s Yijianzhi], 文艺理论研究, 37/6 (2017), p. 45.

[23] Cheng, ‘Traveling Stories’, p. 21.

[24] J. L. Fyler, ‘Social criticism in traditional legends: Supernatural women in Chinese zhiguai and German Sagen’ (Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts, 1993), p. 175.

[25] Y. Zhou and H. Guo, 《理学束缚下的潜抑情欲——论<夷坚志>中的人鬼之恋》[The Suppressed Sexual Desires under the Constraints of New-Confucianism — On the Love between Humans and Ghosts in Yijian Zhi], 江西广播电视大学学报, 2 (2004), p. 35.

[26] Minoru, ‘New developments in the study of Chinese fiction’, p. 139.

[27] M. Liu, ‘Theory of the Strange: Towards the Establishment of Zhiguai as a Genre’, (Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Riverside, 2015), p. 37.

[28] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 967.

[29] J. C. Berry, ‘Animal Demons as Humans: Sex, Gender, and Boundary Crossings in Six Dynasties Zhiguai Literature’ (Ph.D. thesis, Indiana University, 2002), p. 3.

[30] B. J. ter Haar, ‘Newly Recovered Anecdotes from Hong Mai's (1123—1202) "Yijian zhi”’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 23/1 (1993), p. 20.

[31] Hong Mai,《夷坚志》, p. 1135. See a full English translation of the preface of installment zhigeng in Hansen, Changing Gods, p. 20.

[32] S. F. Teiser, ‘Reviewed Work(s): Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127-1276 by Valerie Hansen’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 27/1 (1997), p. 142.

[33] R. Egan, ‘The Tang Dynasty in Song-Period Stories: The Case of Yijian zhi’, Tang Studies, 37/1 (2019), pp. 111-2.

[34] See, for example, Z. Hou, (ed),《中国文言小说参考资料》[References for Chinese Literary Novels] (Beijing, 1985), p. 431. Hu Yinglin, sixteenth-century scholar, criticized Yijian zhi as “靡不成书 (so dispersed that it does not constitute a book)”.

[35] D. Johnson, ‘Communication, Class, and Consciousness in Late Imperial China’, in D. Johnson, A. J. Nathan and E. S. Rawski (eds), Popular Culture in Late Imperial China (Berkeley, 1985), pp. 62-3.

[36] L. T. Chan, ‘Text and Talk: Classical Literary Tales in Traditional China and the Context of Casual Oral Storytelling’, Asian Folklore Studies, 56/1 (1997), pp. 37, 58.

[37] Liu, ‘Theory of the Strange’, p. 46.

[38] Cheng, ’Traveling Stories’, pp. 19-20.

[39] Egan, 《洪迈<夷坚志>中宋代妇女处境之探讨》, pp. 45-6.

[40] Liu, 《盛世繁华:宋代江南城市文化的繁荣与变迁》, pp. 51, 445-6.

[41] Johnson, ‘Communication, Class, and Consciousness’, pp. 38-9, 64.

[42] J. Ye,《论 〈夷坚志 〉叙事的民间性》[A Perspective on Folk Narrative Issue of Record of the Listener], 江西教育学院学报 (社会科学) , 33/1 (2012), p. 133.

[43] B. Zhang, 《两宋时期的社会流动》[Social Mobility in the Song Dynasty], 四川师范大学学报(社会科学版), 2 (1980), p. 64.

[44] 《刘子昂》“Liu Zi’ang” (32), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 222.

[45] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 796-7.

[46] 《小陈留旅舍女》 “Xiaochenliu Lüshe Nü” (4), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 976.

[47] X. Zhu, D. Zhen, et al. (eds),《名公书判清明集》[The Judicial Records], ed. Chinese Academy of History, (Beijing, 1987), p. 353.

[48] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 498-9, 514-5, 1304-5.

[49] See, for example, “Shiliushan Meinü” (7): “君之家人失君久,晓夕叫呼... 君宜遽归 (Your family has been searching for you for a long time. They call your name day and night... It’s best for you to return soon)."

[50] A. Tie, and W. Zeng, 《旅者与精魅:宋人行旅中情色精魅故事论析—以<夷坚志>为中心的探讨》[The Traveler and the Enchantress: An analysis of stories of Song people encountering erotic spirits and goblins in traveling: a discussion centering Yijian Zhi], 中国史研究, 1 (2012), p. 144.

[51] See, for example, 《京师异妇人》“Jingshi Yi Furen” (8),《小陈留旅舍女》 “Xiaochenliu Lüshe Nü” (4),《张三店女子》“Zhang San Dian Nüzi” (28),《建德茅屋女》“Jiande Maowu Nü” (33).

[52] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 65-66.

[53] See, for example, “Jingshi Yi Furen” (8): “吾以金买得之 (I bought her with gold).”

[54] Ebrey, The Inner Quarters, pp. 4, 251.

[55] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 816-7.

[56] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 446-7.

[57] Ebrey, The Inner Quarters, pp. 19-20.

[58] B. Du, 《〈夷坚志〉婚恋小说分析》[An Analysis of Marriage and Love Stories in Yijian Zhi], (Master’s thesis, Sichuan Normal University, 2009), p. 16.

[59] H. You, 《宋代民妇之家族角色与地位研究》[Research on peasant women’s role and status in the family during the Song Dynasty] (Master’s thesis, Tung Hai University, 1988), p. 182.

[60] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 805-6, 801. “崔以人奴获好妇,惬适所愿,不复询究本末。” “仆知为魅也,而庸奴贪色,竟留与接。”

[61] 《郑四妻子》“Zheng Si Qizi” (14), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1262.

[62] Ebrey, The Inner Quarters, pp. 250-1, 260.

[63] P. Ebrey, ‘Women, Marriage and the Family in Chinese History’, in P. Ropp (ed), Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives on Chinese Civilization (Berkeley, 1990), p. 223.

[64] Zhou and Guo, 《理学束缚下的潜抑情欲》, p. 35.

[65] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 746-7.

[66] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 976.

[67] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 55-6.

[68] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 953-4.

[69] Tie and Zeng, 《旅者与精魅》, p. 144.

[70] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 976.

[71] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 1697-8.

[72] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 147, 1627. “...... 容状伟硕.两股文绣飞动.谛观慕之.眷恋不能去.” “见土偶素衣美容,悦慕之,瞻视不能已.” See more in Cheng’s thesis on the erotic power of humanlike statues and images in the Song Dynasty.

[73] 《建德茅屋女》“Jiande Maowu Nü” (33), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 1373-4.

[74] Berry, ‘Animal Demons as Humans’, p. 98.

[75] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 446-7.

[76] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 695-7.

[77] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 717-8.

[78] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1425.

[79] Ma, 《论 <夷坚志>中的女性形象及其妇女观》, p. 55.

[80] See the extract and translation at the top of page 3.

[81] H. Dou (ed), 《宋刑统》[A Comprehensive Records of Song Law Codes] (Beijing, 1984), p. 223. The law code also specified that a wife’s desertion of husband was punishable by two years of servitude.

[82] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 268.

[83] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 369.

[84] Cheng, ‘Traveling Stories’, p. 108.

[85] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 1489-90.

[86] As illustrated in “You Jiefu” (15), where the peasant Ning Liu refused to bribe the local prison officer who then reported You’s fabricated charge against Ning Liu to the Prefecture of Jianchang.

[87] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 902.

[88] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 797.

[89] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 701, 805. “黄或窘索.必窃资给之.” “袖出官券十千与之. 其后屡致薄助...”

[90] “Xiaochenliu Lüshe Nü” (4), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 976. “... 其色赧赧然若负愧之状。”

[91] “Wu Langjun” (24), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 717.

[92] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 1690-2. “米中得北珠数颗。自是每日皆然,转盼成富人,建第宅。”

[93] “Qiu Ding Ruming” (18), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 953-4.

[94] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 755.

[95] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 499.

[96] 《钱炎书生》“Qian Yan Shusheng” (36), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 1755-6.

[97] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 755.

[98] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1692.

[99] 《建昌王福》“Jianchang Wang Fu” (19), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 766.

[100] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1801.

[101] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 222.

[102] “Chapu Cui San” (13), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 805-6.

[103] Daoist priest who allegedly expelled an evil spirit from a woman and made her disappear sometimes faced legal consequences. See examples in 《京师异妇人》(pp. 65-6) and 《鄂州南市女》(pp. 1136-7).

[104] “Jiande Maowu Nü” (33), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 1373-4. In this story, Cai Wu ran away from an uxorilocal marriage and later got together with this woman. So it was unclear whether they went through official marriage rites. Cai Wu referred to her as his wife, but the narrator referred to her only as “the woman”.

[105] Zhou and Guo, 《理学束缚下的潜抑情欲》, p. 36.

[106] Yijian zhi contains several stories on the unfilial shrew dying horribly or turning into animals. A similar metamorphosis also occurs in people who kill animals extensively.

[107] Zhou and Guo, 《理学束缚下的潜抑情欲》, p. 36.

[108] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1490.

[109] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 59-60.

[110] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 60.

[111] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 1697-8.

[112] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 787, 1755-6.

[113] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1564.

[114] M. Powers, ‘‘Humanity and ‘Universals’ in Song Dynasty Painting’ in M. Hearn and J. Smith (eds), Arts of Song and Yuan (New York, 1996), pp. 140-1.

[115] On the notion of passivity, in Cheng, ‘Traveling Stories’, p. 120, she argues that adultery could be disguised in exorcistic rhetoric, which turns the women from passive object to active subject of desire.

[116] Tie and Zeng, 《旅者与精魅》, pp. 149-50.

[117] “Zheng Si Qizi” (14), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1262.

[118] 《游节妇》 “You Jiefu” (15), in Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 746.

[119] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, pp. 960-1.

[120] Hong Mai, 《夷坚志》, p. 1564. In this story, the severely ill Zhou You reported his wife’s mistreatment of him and her affair to his general. He died a moment later after she was beheaded.

[121] Ebrey, The Inner Quarters, p. 271.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Printed

Dou, H. (ed),《宋刑统》[A Comprehensive Records of Song Law Codes] (Beijing, 1984)

Hong, Mai,《夷坚志》[Yijian zhi], ed. J. He, (Beijing, 1981)

Hou, Z. (ed),《中国文言小说参考资料》[References for Chinese Literary Novels] (Beijing, 1985)

Zhu, X., Zhen, D., et al. (eds),《名公书判清明集》[The Judicial Records], ed. Chinese Academy of History, (Beijing, 1987)

Secondary Material

Books and Articles

Allen, S. M. and Chen, J. W., ‘Fictionality in Early and Medieval China’, New Literary History, 51/1 (2020), pp. 231-34

Campany, R. F., Strange Writing: Anomaly Accounts in Early Medieval China (Albany, 1996)

Chaffee, J., ‘Introduction: Reflections on the Sung’, in J. Chaffee and D. Twitchett (eds), The Cambridge History of China (15 vols, Cambridge, 2015), pp. 1-18

Chan, L. T., ‘Text and Talk: Classical Literary Tales in Traditional China and the Context of Casual Oral Storytelling’, Asian Folklore Studies, 56/1 (1997), pp. 33-63

Chen, X. and Qin, B.,《经与权:中国传统女性观与妇女生活的变迁》[Classics and Power: Changes within the Chinese traditional view of women and women’s lives] (Sichuan, 2015)

Ebrey, P., ‘Women, Marriage and the Family in Chinese History’, in Ropp P. (ed), Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives on Chinese Civilization (Berkeley, 1990), pp. 197- 223

Ebrey, P., The Inner Quarters: Marriage and the Lives of Chinese Women in the Sung Period (Berkeley, 1993)

Ebrey, P., ‘Engendering Song History’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 24/1 (1994), pp. 340-346

Egan, R.,《洪迈<夷坚志>中宋代妇女处境之探讨》[Exploring the Lives of Song Dynasty Women through Hong Mai’s Yijianzhi], 文艺理论研究, 37/6 (2017), pp. 44-9

Egan, R., ‘The Tang Dynasty in Song-Period Stories: The Case of Yijian zhi’, Tang Studies, 37/1 (2019), pp. 111-128

Haar, B. J. ter, ‘Newly Recovered Anecdotes from Hong Mai's (1123—1202) ‘Yijian zhi’’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 23/1 (1993), pp. 19-41

Hansen, V., Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127-1276 (Princeton, 1990)

Johnson, D., ‘Communication, Class, and Consciousness in Late Imperial China’, in Johnson, D., Nathan, A. J. and Rawski, E. S. (eds), Popular Culture in Late Imperial China (Berkeley, 1985), pp. 34-72

Liu, F.,《盛世繁华:宋代江南城市文化的繁荣与变迁》[Prosperous times: the prosperity and changes of urban culture in Jiangnan during the Song Dynasty] (Hangzhou, 2011)

Ma, Y.,《论 <夷坚志>中的女性形象及其妇女观》[On the Image and View of Women in Yijian zhi], 高等函授学报(哲学社会科学版), 27/12 (2012), pp. 53-7

Minoru, K., ‘New developments in the study of Chinese fiction—Theoretical issues and a discussion of the application of the colloquial story (xiaoshuo/小说) to the study of social history’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 35/1 (2005), pp. 138-150

Powers, M., ‘‘Humanity and ‘Universals’ in Song Dynasty Painting’ in Hearn, M. and Smith, J. (eds), Arts of Song and Yuan (New York, 1996), pp. 135–145

Saler, B., ‘Supernatural as a Western Category’, Ethos, 5/1 (1977), pp. 31-53

Teiser, S. F., ‘Reviewed Work(s): Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127-1276 by Valerie Hansen’, Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 27/1 (1997), pp. 137-147

Tie, A. and Zeng, W., 《旅者与精魅:宋人行旅中情色精魅故事论析—以<夷坚志>为中心的探讨》[The Traveler and the Enchantress: An analysis of stories of Song people encountering erotic spirits and goblins in traveling: a discussion centering Yijian zhi], 中国史研究, 1 (2012), pp. 139-54

Watkins, C. S., History and the Supernatural in Medieval England (Cambridge, 2007)

Xu, S.,《宋代妇女史研究述评》[A Review on the Research of Women’s History on Song Dynasty], 浙江理工大学学报 (社会科学版), 40/5 (2018), pp. 487-95

Ye, J.,《论 〈夷坚志 〉叙事的民间性》[A Perspective on Folk Narrative Issue of Record of the Listener], 江西教育学院学报 (社会科学) , 33/1 (2012), pp. 132-5

Zeitlin, J., Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale (Stanford, 1993)

Zhang, B., 《两宋时期的社会流动》[Social Mobility in the Song Dynasty], 四川师范大学学报(社会科学版), 2 (1980), pp. 61-7

Zhou, Y. and Guo, H.,《理学束缚下的潜抑情欲——论<夷坚志>中的人鬼之恋》[The Suppressed Sexual Desires under the Constraints of New-Confucianism — On the Love between Humans and Ghosts in Yijian zhi], 江西广播电视大学学报, 2 (2004), pp. 34-6

Zhang, Z., Hidden and Visible Realms: Early Medieval Chinese Tales of the Supernatural and the Fantastic (New York, 2018)

Unpublished Theses

Berry, J. C., ‘Animal Demons as Humans: Sex, Gender, and Boundary Crossings in Six Dynasties Zhiguai Literature’ (Ph.D. thesis, Indiana University, 2002)

Cheng, H., ’Traveling Stories and Untold Desires: Female Sexuality in Song China, 10th-13th Centuries’ (Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington, 2012)

Du, B.,《〈夷坚志〉婚恋小说分析》[An Analysis of Marriage and Love Stories in Yijian zhi], (Master’s thesis, Sichuan Normal University, 2009)

Fyler, J. L., ‘Social criticism in traditional legends: Supernatural women in Chinese zhiguai and German Sagen’ (Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts, 1993)

Liu, M., ‘Theory of the Strange: Towards the Establishment of Zhiguai as a Genre’, (Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Riverside, 2015)

You, H.,《宋代民妇之家族角色与地位研究》[Research on peasant women’s role and status in the family during the Song Dynasty] (Master’s thesis, Tung Hai University, 1988)

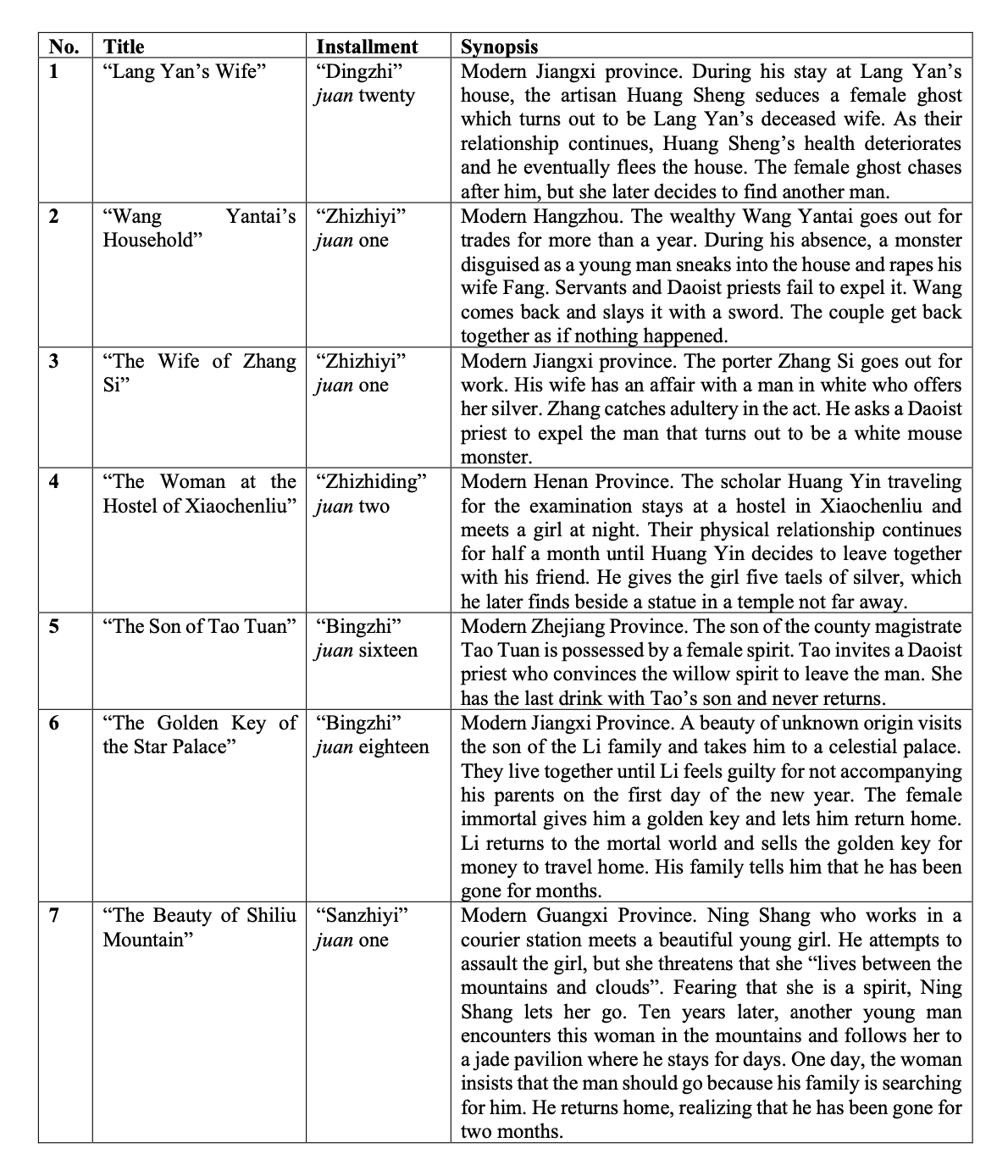

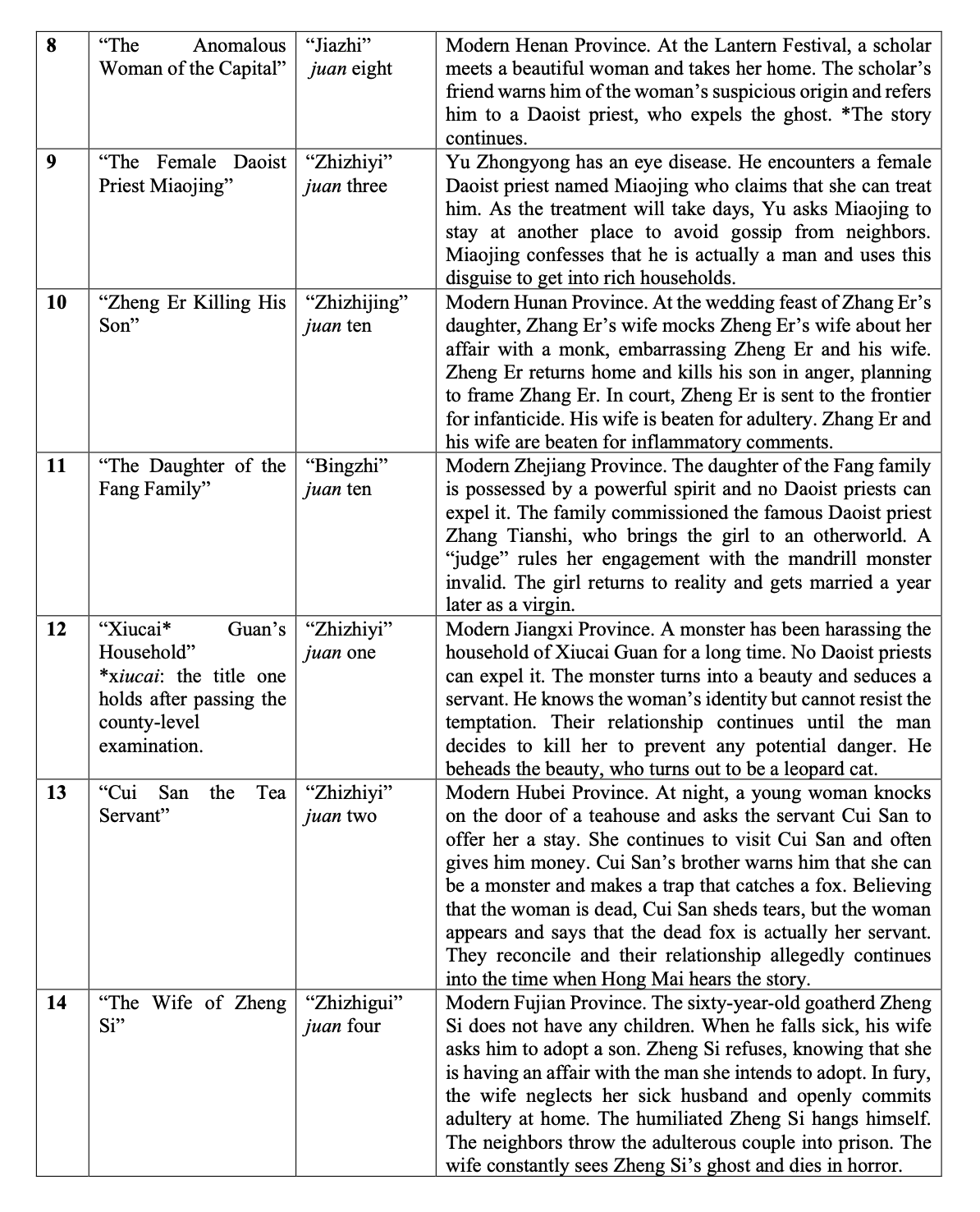

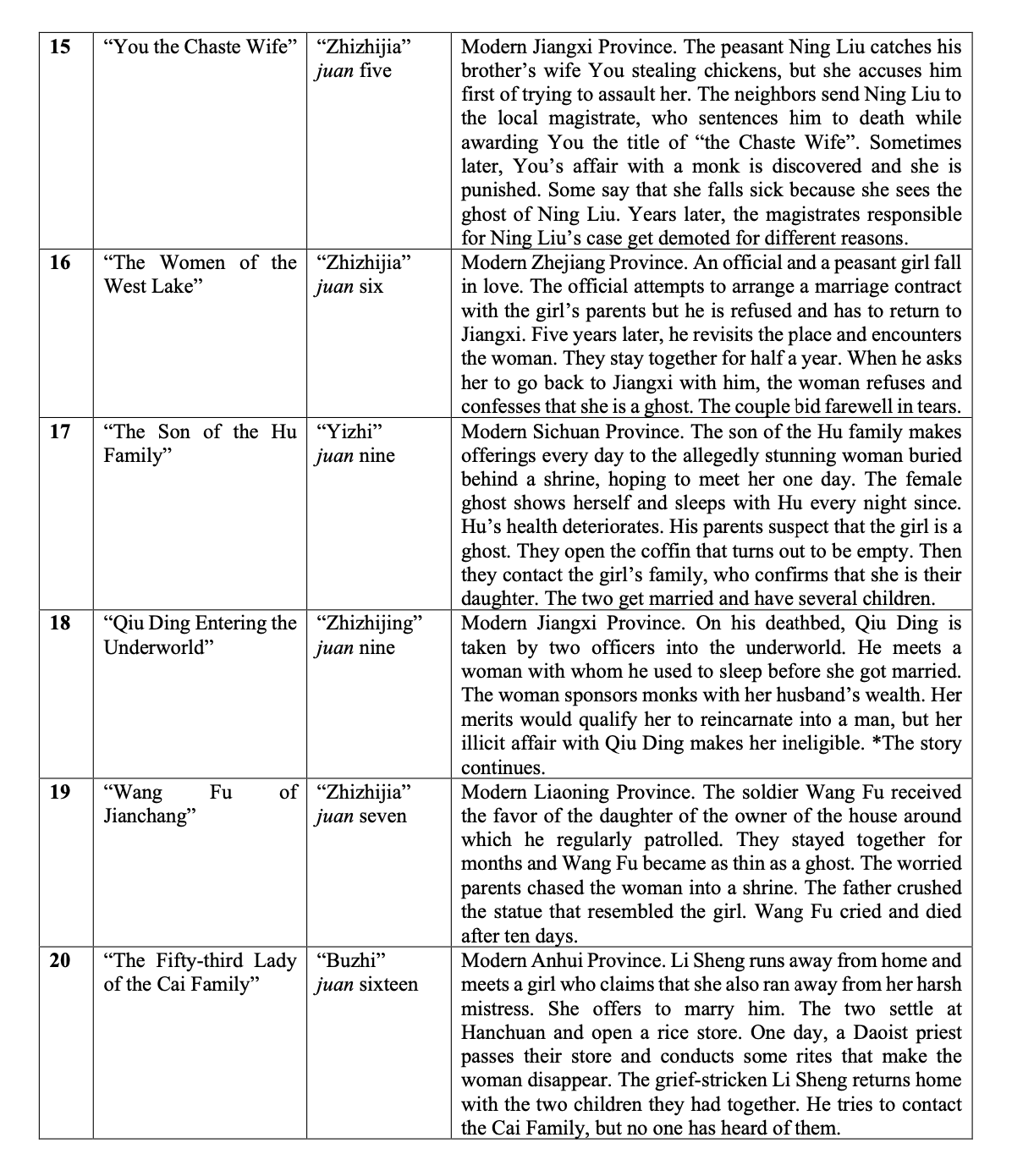

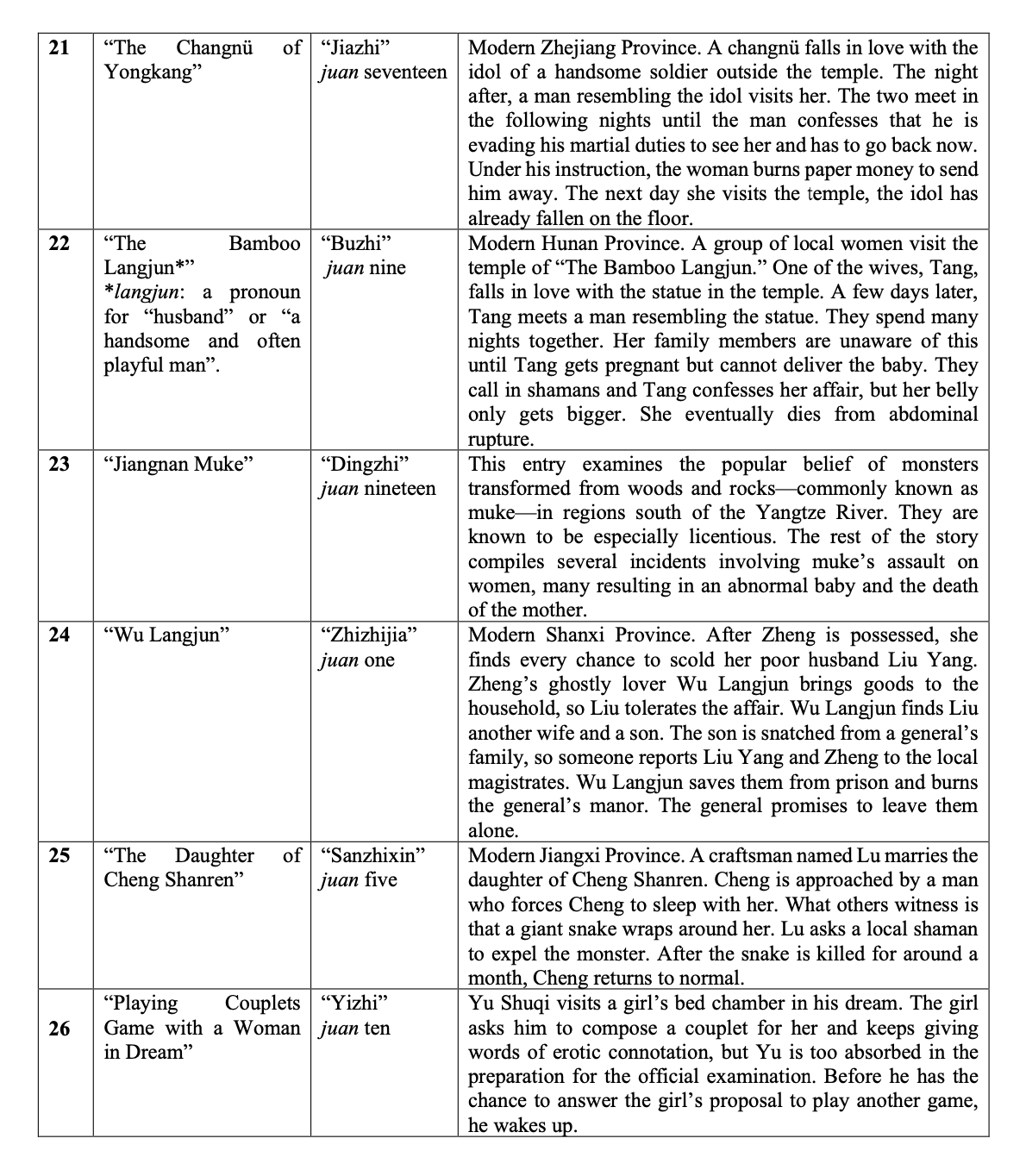

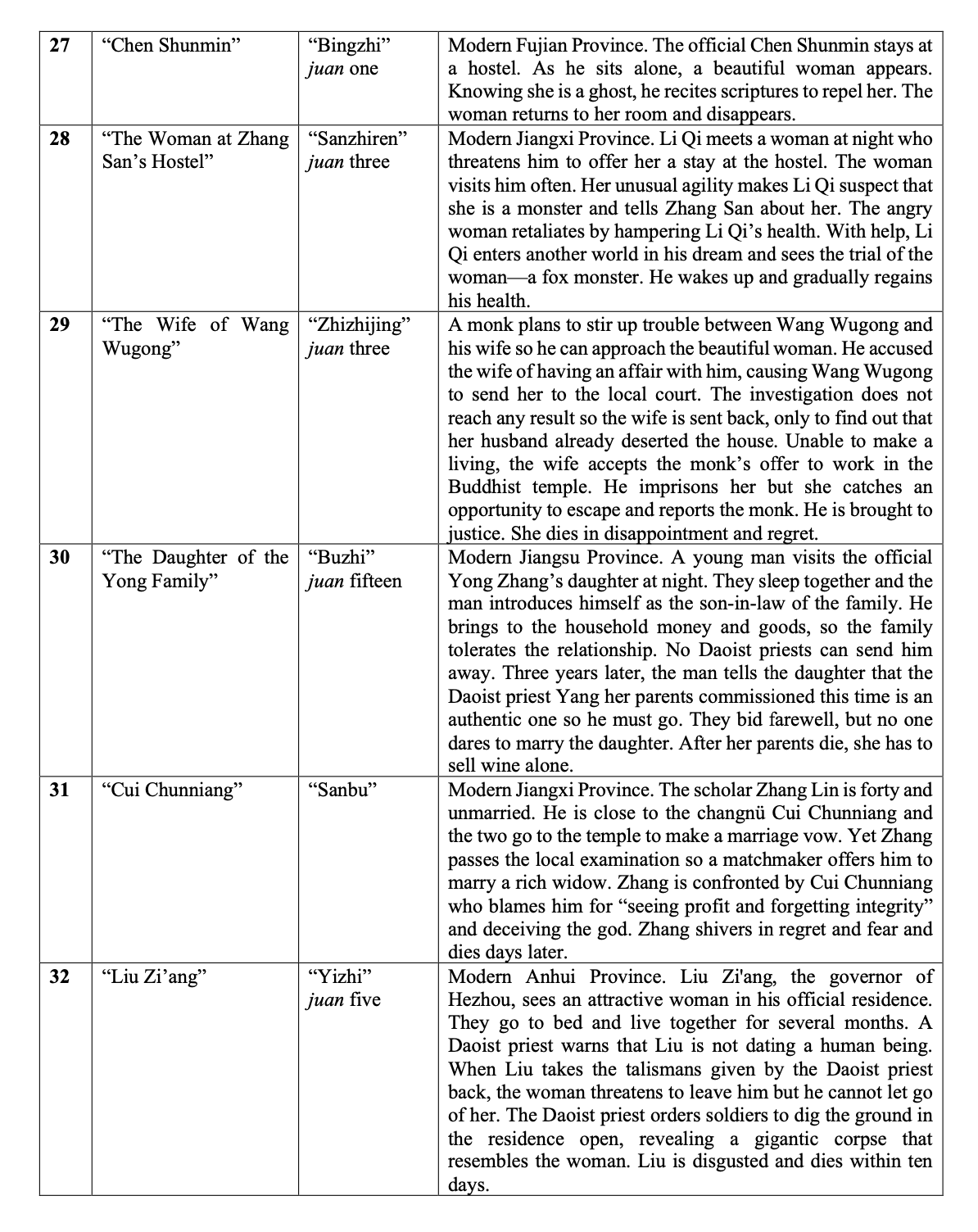

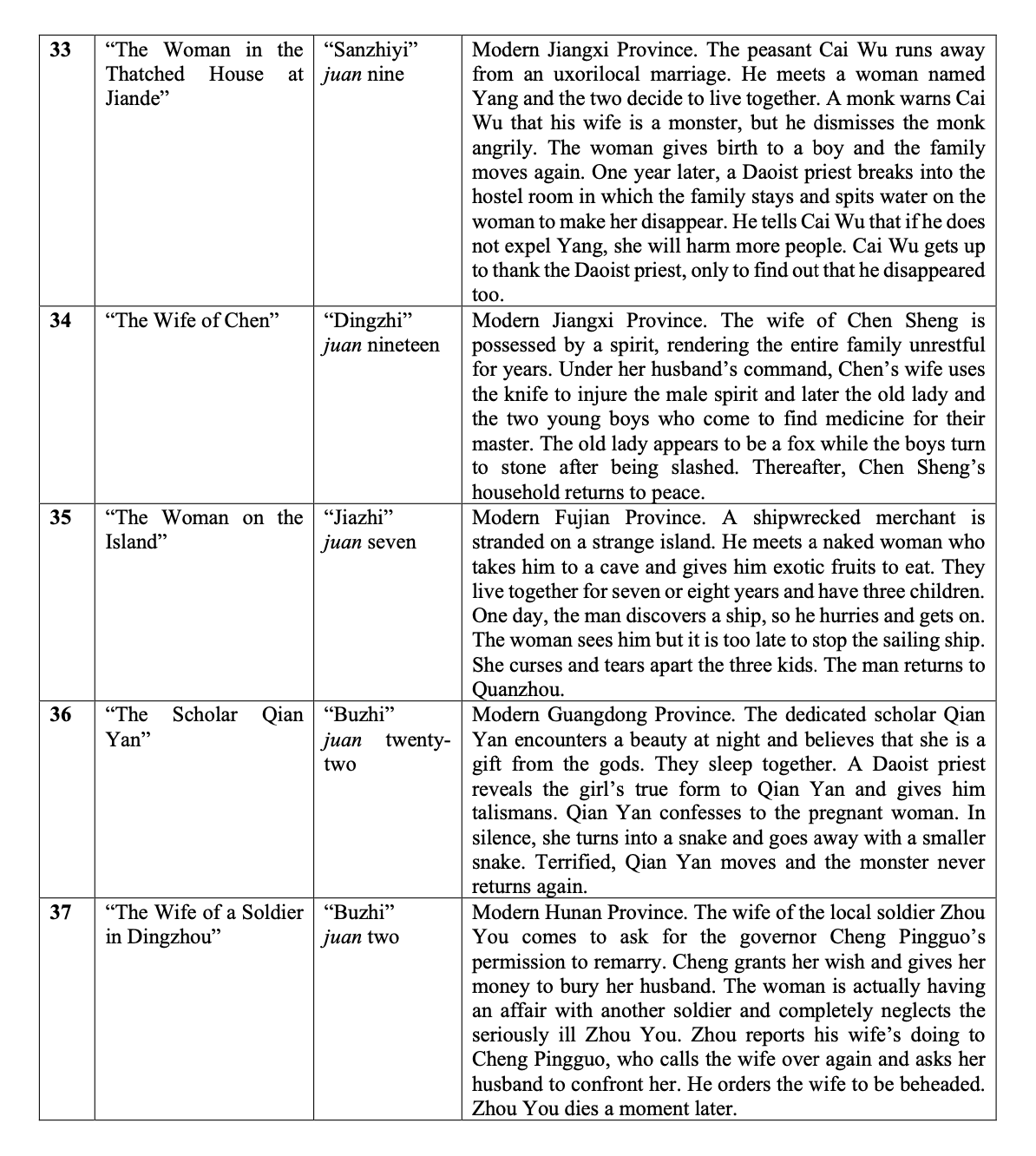

Appendix

Synopses of Selected Stories from ‘Yijian zhi’

Details and sections that are irrelevant to the analysis in this study have been omitted.