By Libby Hoffenberg, Swarthmore College '20

Advised by Professor Timothy Burke

Edited by Daniel Ma, Gabby Sevillano, and Katie Painter

INTRODUCTION

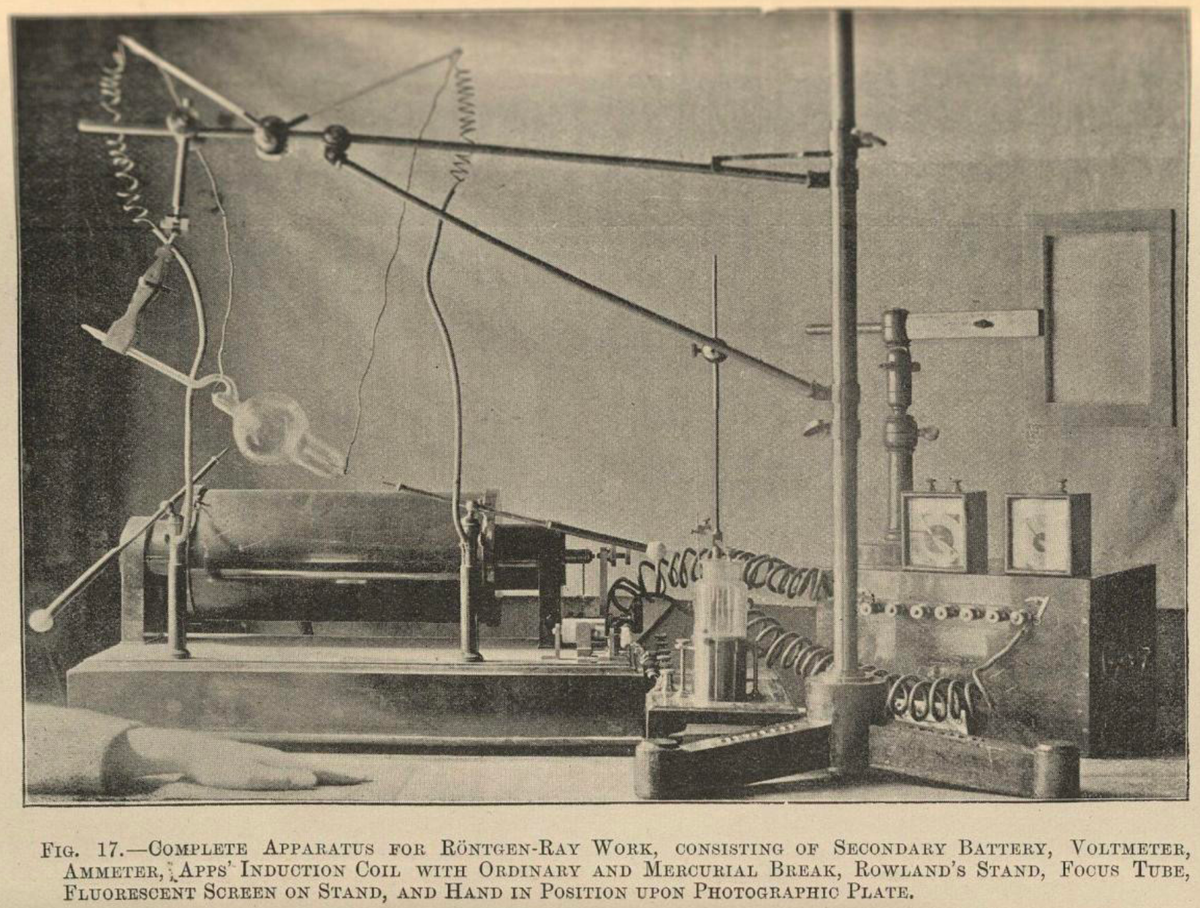

In November of 1895, physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered a wavelength of electromagnetic radiation that came to be known as the “x-ray” or the “Röntgen ray.” Within months, experimenters and laypeople were producing x-ray images using a simple set of machinery. In order to make an x-ray exposure, one needed just three elements: a current source, a Crookes tube, and a photographic plate. Although the process was relatively simple, material limitations made the apparatus brea- kable, bulky, and unreliable. Historians have referred to this phase of the x-ray’s existence as the “gas tube era,” which more or less ended in 1913 when stronger and more versatile equipment was developed.

The unwieldiness of the x-ray machine as a physical object mirrored its clumsy implementation in various medical and non-medical enterprises. The x-ray was regarded with fascination as a device that clearly did something—it “miraculously” revealed the body’s interior and produced outwardly observable effects on the body—but it had ambiguous uses and meanings. It was entertained as a therapeutic tool in treating everything from blindness to cancer, a photographic novelty that produced chic and “coquettish” images of women of means, and a way to substantiate prosecuted criminals’ claims to insanity, among many other uses.

Historians have duly noted the dramatic public reception of the x-ray, as well as many of its initial experimental applications. Theorists in visual studies particularly emphasize the public’s reaction to the x-ray as “spectacle” and the capitalization of novelty by professionals of various standings to substantiate their authority. This interpretation importantly complicates teleological narratives of the x-ray and articulates the multiple and unstable significations of a new technology. It upends the idea that the x-ray was, from its inception, destined to claim the authoritative place it holds in current healthcare practices. It affirms that technologies do not arise in response to pre-existing needs, but they become institutionalized by and in service of contingent relations of power.

Most histories of the x-ray, however, consider its development as a diagnostic screening tool and fail to consider, or make only cursory reference to, its use as a therapeutic agent. These accounts obscure the epistemological complexities implied by the selection of the nascent technology’s diagnostic use over its therapeutic one. In this chapter, the narrowing epistemic field of the x-ray is considered alongside the shifting contexts and contents of American medicine. Across approximately the first half of the twentieth century, multiple potentialities of the x-ray were winnowed to a single diagnostic use just as a modern scientific healthcare paradigm was emerging. In other words, the x-ray technology and its symbolic power evolved alongside changes in the knowledge practices sanctioned by modern healthcare. The negotiation of the x-ray’s potentialities can be contextualized by investigating how the uses for the x-ray were entertained in a medical context that was itself uncertain. Different philosophies, metaphors, and interests were called upon to justify its privileged position as a device of specialized visibility.

While the x-ray was invented in Germany, many novel uses of and deliberations over the technology took place in American hospitals, journals, and other sites of medical activity. The x-ray’s early days of use and experimentation—from its invention in 1895 until roughly 1940 reveal an unruly history that broadly parallels navigations of ambiguity in the American medical system. The x-ray moved through a series of epistemological and professional paradigms, each of which shaped and were shaped by x-ray practice. The x-ray debuted in a medical system that was largely constituted by idiosyncratic doctor-patient relationships, which were themselves relatively closed worlds of therapeutic practice. In the context of this testing ground, the x-ray proved amenable to a number of explanatory frameworks, as eclectic practitioners integrated thedevice into their own ideological priorities. Many early practitioners understood the x-ray’s therapeutic potential in relation to other therapeutic uses of electricity, thus revealing the technology’s absorption into vitalistic, or spiritualized, medical paradigms.

During the x-ray’s “middle years,” approximately 1900 to 1918, the technology assumed an aura of professional appeal based on its capacity to authoritatively image the body’s interior. At this time, the x-ray became privileged for its capacity to produce certain scientifically verified images. The ascendance of the x-ray’s diagnostic use sheds light on the growing primacy of visual knowledge, and specifically of mechanically-produced images, within medical practice.

In its post-WWI years, the x-ray became embedded in large industrial-scientific medical institutions. It was in this context of broad redefinitions of healthcare that the x-ray assumed its diagnostic legitimacy, taking its place alongside a host of other organizational and information technologies that tethered together the practices of different physicians into a single system. At this time, healthcare was increasingly reconfigured as a business that was premised on the modern individual’s health-seeking efforts.The x-ray helped to produce the notion of the body as a site of continual maintenance, as it made the authoritative visualization of the body’s interior a coordinating principle for diagnostic activity. Esteemed medical professionals increasingly augmented their medical judgment with the x-ray’s technologically-advanced capacity to objectively discern the most fundamental structures of any individual.