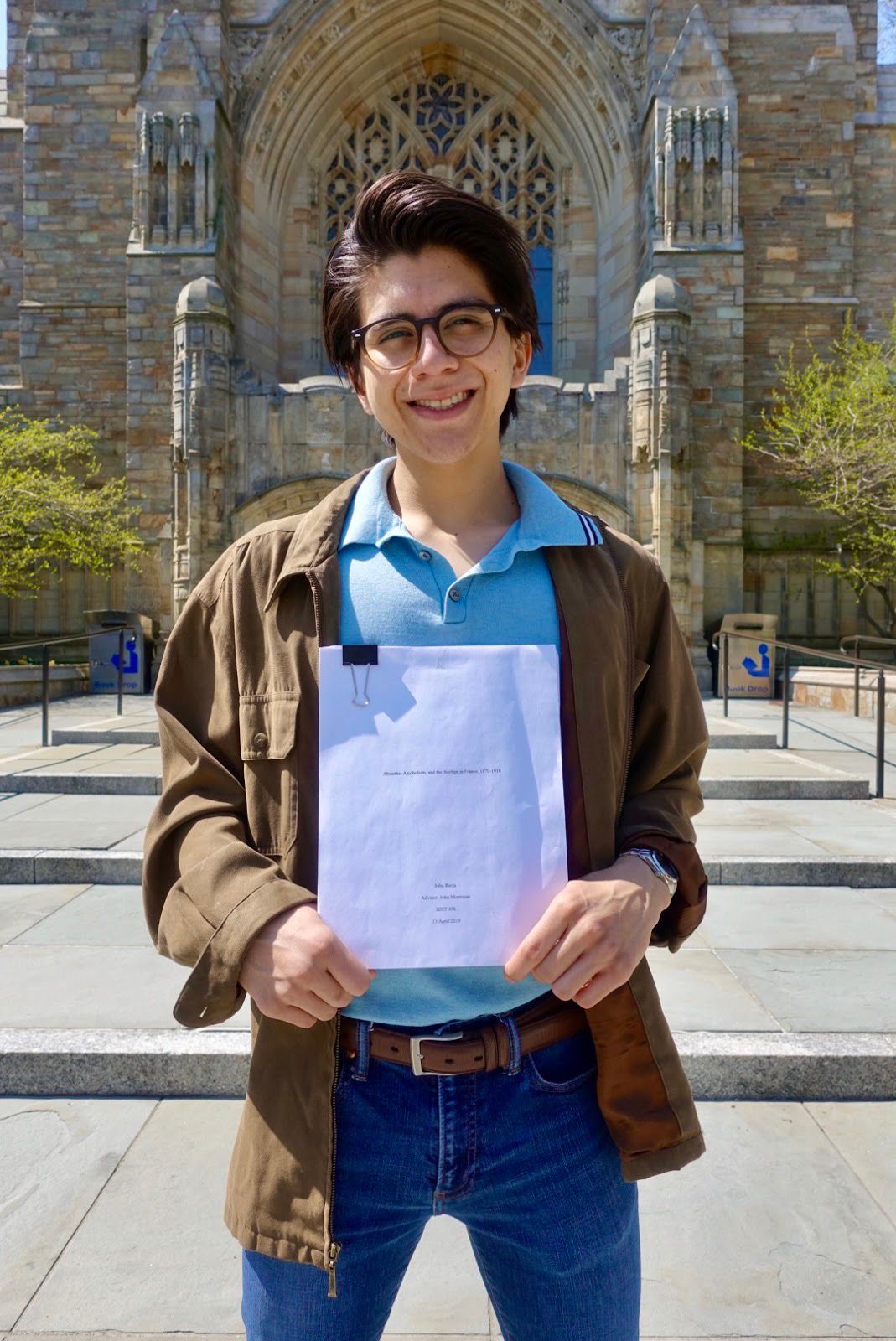

Isabella Smeets sits down with John "JJ" Borja, author of Absinthe, Alcoholism, and the Asylum in France, 1870-1918.

Isabella Smeets (IS): Firstly, I was just wondering what inspired you to write about Absinthe, Alcoholism, and Asylum in France from 1870-1918?

John Borja (JB): I think the first thing was taking John Merriman’s History of Revolutionary France 1789-1871 lecture during my first semester at Yale. At some point in that course, he started talking about absinthe and silk. It got me interested in the beverage. He was telling us about how absinthe has these certain effects; it makes you hallucinate, it’s green, the wormwood, and all that fantastic stuff. I got back to my dorm after that class and I talked to my friend. I asked him, “Have you heard of this stuff, absinthe?” And he said “Yes, it's just a regular alcohol. There’s nothing special about it.” But I told him about what John Merriman said, and we got into this debate about wormwood and the active chemical, thujone. I was stuck there for a while. I continued through school, learned more, and eventually I started to piece the themes of my senior essay together. I knew I wanted to study absinthe for my senior essay by the spring of my junior year. As I was starting out, I knew there was something weird about absinthe. It either did have these effects or didn’t have these effects, but I knew that it really couldn’t be both. So I tried my hardest thinking of all the ways that I could reconcile this paradox and how I could bring these two sides of the argument together. It took my senior year to actually get that together, find all the different threads, and make sense of them. It was mostly Foucault that was able to do that, so that's why he's [such a heavy influence] in the essay. I couldn't really make sense of the contradictions within the discourse without Foucault, so I needed that. It was a risk for sure because not everybody supports that methodology of addressing these kinds of things.

IS: You also talk about using the Archives Départementals of the Doubs in Besançon and the municipal archive of Pontarlier. How did you discover and decide to use these records?

JB: The first thing was that I knew I needed to go to France. I knew I wanted to be in the records.

At the end of the day, regardless of what I studied, I wanted to be in the archives and do original archival research as the capstone of the history major. So, I talked to John Merriman about this, and he was on board with absinthe. He told me to read Susanna Barrows who had worked at Yale for a number of years herself. Michael Printy, Yale’s librarian for Western European Humanities, was a student of hers and a huge asset to my research. Barrows had been a pretty big figure at Yale and within the history of alcoholism. So, I kind of took her lead there with some of the primary sources. But to get down to the actual archives that I was using, I consulted John Merriman who was my advisor throughout the whole thing. I started this process in January of 2019. He told me that the departmental archives of the Doubs would be the key archive to explore; John is the master of departmental archives. He is exhaustive; he’ll go to every departmental archive in France when he does his research. I was not prepared to do the same just yet; I knew I wanted to target Pontarlier, which is the center of absinthe production. I needed to get to the departmental archives to get a lot of the local, governmental stuff that was happening there. Then I wanted to go to the Municipal Archives. I actually got more out of that visit to the Municipal Archives than any of the other archives; it had a lot of really deep information about absinthe production and unionization, as well as quite a bit of secondary literature from past archivists and researchers. And basically, more or less, every historian that has studied absinthe in France has had to go through that archive in one way or another. I was able to work closely with the archivists at those archives, which was a super big resource because they know where everything is and they remember researchers from years past who found use in certain documents. They were extremely helpful, and they were familiar with my topic. I convinced them that I was not just some American, but that I actually knew what I was studying. So gaining their trust and support allowed me to dig deeply into the archives. But I chose those archives mainly with the guidance of John Merriman. I also went to the National Archives in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, Paris, but I didn't get much out of those archives to be honest.

IS: You speak a lot about your thesis advisor John Merriman’s influence on your thesis and all of his help. I was wondering more about his role in your thesis. How did you get connected with him in the first place? Was your first interaction with him in the lecture you took?

JB: It was really through his classes that I got to know John. It’s been a long connection. I've known John since my first semester of freshman year. I took his class, and I loved it. Then I thought, “Okay, I need to get more of this man. I love this guy, and he's a very unique teacher.” I don't know that I've had any teacher, in history or otherwise, that that is quite like him. I trust him as a historian and as a political actor. I took a junior seminar with him the second semester of my freshman year which was all about Vichy France, and I was totally unprepared. The final essay for that class was the first semi-substantial work I'd written, and John helped me go through it. He was super encouraging the whole time, even though I was falling flat on my face. He encouraged me by telling me that “your French is there, your research is there, your story is there.” He helped me refine my writing and epistemology. In particular, he started pointing out my presumptions about the normal people’s relationship with religion and ideology, which helped me to grow in my historical thinking. He really pushed me to think empathetically but critically and not take cause and effect as a given. He honed down my historical methodology, and I took basically every class that he offered. It was unfortunate that I could never take the second half of that 1871 to present day French history class, but I took every other class that I could with him. Those experiences were super beneficial, and I gained that social-historical methodology focusing on “history from the margins” from them. I reference a number of Merriman’s books, as well as collections that he edited, a number of times throughout my thesis. He laid the groundwork for a lot of the social research within French history, especially with regard to the labor and policing movements. He knows fin-de-siècle France, the “crime” within it, and the relationship between the government and crime better than any historian that I've met. So I really relied on his research but also his mentorship over the last four years. He was there helping me decide on my classes each semester. He was there when I was deciding to go to Nantes, France to study abroad. He's just been one of those people that everyone knows within my field of study. So if I go anywhere within the history department, they know John Merriman. They know his work and all that, so they often know where I stand on certain issues. Having a really strong mentor relationship and someone that you can really adopt their way of thinking will set you up for a really strong foundation to go do your own thing. John Merriman and I really diverged methodologically in this essay, and yet he was fully supportive of it. He was fully supportive of my critique of the discourse of alcoholism and insanity, which I discovered in his class. He's been involved in every step of the way.

IS: I was also wondering, in general, how you went about conducting your research? You’ve mentioned of course going to the archives in France, but I was wondering if you made use of any of Yale’s resources as well?

JB: Yeah, Yale has some of the best archives and research systems in the world. I don’t know that anyone has a library system like Yale; you can find any book on any subject and a librarian with immense knowledge to aid you. Most of the books I was researching were written in the eighties because that’s where the historiography really leaves off. There were a couple popular reproductions which just recycle the myths of absinthe as something completely hallucinogenic and mind boggling. The real historiography is found in the 1980s; most of what I utilized historiographically left off at about 1984. Without Yale and its librarians, I wouldn't have been able to access all of those works and get a hold of some really esoteric historical journals. That was all for my secondary source research; the rest was archival, but I really started with Yale. I checked out every book with the keyword absinthe and went through them for the first six months. The first thing was digging into the precise history; I got a number of books on Pontarlier. I started with the basic stuff, trying to break down the science, going into medical journals, trying to draw conclusions. A lot of pharmacologists have studied Van Gogh and have tried to see what the connection is between his mental mental illness and his alcoholism (he had a love of absinthe). Later on, this type of research would become part of my critique of the discourse of alcoholism. So by then I had the basic details, and I could write a basic paper about what happened in Pontarlier and France around 1915. Then I started studying laws and prohibition; I was looking at the progression of restrictions on alcohol consumption. There was basically a firm line in the sand in 1914 that there would be no more absinthe. Yet, I couldn’t find any records from 1914 in the National Archives, the departmental archives, or the Municipal Archives. There was nothing. All I could find were documents discussing how they were going to collect all the absinthe when they made it illegal. They also discussed how they were going to reasonably compensate all of the ingredient producers. When I talk about how the political economy of prohibition set up the unique terms of absinthe’s interdiction, I am talking about how it took absinthe’s opponents in the government a really long time after 1907 to figure out how exactly they were going to make the drink illegal resolutely. So I started studying the change and discourse and asking myself why it started to shift in 1907. There are a number of reasons: the revolt, the media, World War One militarisation, the rise of psychiatry, and the colonies. I say in the essay that there is something very colonial to this discourse. My work is incomplete; I need to research and reconcile the situation in the colonies, particularly Tunisia and Algeria, where absinthe was also made illegal at the exact same time. I am still contemplating the role of interdiction in North Africa, and I really can't get there. I'm stuck without those archives and perspectives. I know one researcher is studying this exact phenomenon. Dr. Nina Studer, who is presently at the University of Bern, is studying alcohol/absinthe within Algeria. Her work addresses many of the exact dimensions I discuss in my essay, including the relationship between the asylum/psychiatry and women, class and drinking culture, Christianity and Islam, and, of course, civilized settler and questionably-civilizing native. Her work is the bridge between the two contexts and will lead the way for future research on the subject. Dr. Studer has done groundbreaking research for the history of alcoholism in Algeria, and her upcoming publications should accelerate the research in the field dramatically.

IS: That would be some very interesting additional research! Going back to your thesis, in your introduction you write about your aims, and you proclaim “I am to provide an image of French temperance as the legislative product of a long genealogy that intricately links alcohol consumption to the social isolation of the physically disfigured/disabled and the mentally ill, the degeneration of individuals and their descendants, the transfer of venereal disease, political revolution (especially following the Paris Commune in 1871 and the Révolte du Midi in 1907), and a threat to the industrial prosperity of the nation.” This is a weighty and well thought out argument! Did you go into your research with this idea in mind or did you cultivate your argument through your research process?

JB: Definitely through the process. As I said before, I started with the ontology, the bare “facts” about absinthe. Then I was stuck. I didn't have an epistemology, a framework that could link all these ideas together. I began with the social framework, with John Merriman talking about action and agency on a ground level, how communities are formed, and how ordinary people exert influence. But, I didn't really understand the concepts that were more abstract, like degeneration and eugenics. Also, the scientific mechanisms by which all these things are carried out were not as well established as today. So I knew I couldn’t go with a fully modern scientific lens because this particular lens would not have existed at the time. They didn’t have the same research, institutional structure, or presuppositions as researchers and advocates today; the particular form of scientific research we have today would have been completely unavailable to anyone back then. But at the same time, I can't just buy into the discourse that there's something inherently different about absinthe just because people said it in archived works and official documents. I took a seminar with Professor Carolyn Dean, who is a professor and researcher of intellectual history, and overall it was her class that transformed the way I approached this history. I got a solid, historical foundation in my first few years at Yale, but it was in Carolyn Dean's class, called “Readings in European Cultural History,” that really did the 180. It was there that I discovered Foucault in the way that I did and genealogy as a way to explore my subject. So rather than that chronology, I talked about how there's this gap between 1907 and 1914 and how genealogy solves that gap. It doesn't matter if it's a day or seven years, because genealogy allows me to connect the discourses to the documents that I do have without necessarily having to find a proximate cause and effect relationship, the exact tie that links it all together. It also allowed me to broaden my scope geographically and culturally. It allowed me to go and compare the situation in France with the histories of prohibition (or lack thereof) in different provinces in Canada, in the United States, in Northern Europe, and all these places. I was getting that cultural, historical perspective particularly through post-structuralist philosophers. I certainly mentioned Foucault a lot; Society Must be Defended is one of those works. I also mentioned Madness and Civilization. I started with this idea that there was something disfiguring about absinthe, and it started to make a lot more sense. So starting with the leper and physical disfigurement allowed me to connect it very strongly with all the media imagery of absinthe which primarily showed disabled, outwardly-different persons. You don't find a single image of the absinthe drinker where they are an upstanding bourgeois white male citizen. It’s a dirtier, if not darker skin, generally feminine, generally in the form of a prostitute, green person. There’s fire, purity, and bystanders looking by and saying, “Look at what this non French person has done to our race.” This idea of race is super strongly fed within Foucault’s genealogy. There’s the philosophy of Foucault and there’s his genealogies. I adopted both the genealogies and the methodology for this project, starting with the history of the lepers, and then moving up through the consecration/medicalization of ideas about physical/mental difference, and how the psychiatric turn in particular started to unite those two with a particularly eugenic goal. I'm bringing the discourse to alcoholism, which is something that Foucault only mentioned early in his genealogy, but then really gives up later. So I'm trying to fill in his project with my essay. I see this project as a genealogy that extends into today: the war on drugs and all this stuff. My project is to propose a pretty transparent genealogy that you can apply both to today and the past. I was trying to link the two, so that was what I was really going for at the end. But at the beginning, I had no clue that that’s what it was going to be. I started with the idea that absinthe may be hallucinogenic or may not be. But then it turned out to be the whole discourse of hallucination; the physical difference and mental difference. I tried to make a lot of historical points as well about population, natalism, and all that to bring it more into focus without the abstract kind of genealogy that I'm referencing constantly.

IS: A more general question: Did you go into Yale knowing that you wanted to be a history major? Did you ever consider studying French?

JB: This is interesting because I studied history in high school, and I was fond of it. I really liked it, and by my senior year I was set on political science with maybe history as a minor (were I not to attend Yale). I did a program called Freshman Scholars at Yale and that took me away from political science. I was not into it. So I started doing math, and math was actually what I wanted to do during my first year at Yale. But I took MATH 230, fell flat on my face, and at the same time I was taking John Merriman's class. I realized that I wasn't doing any of my MATH 230 work, but I was doing every single page of reading for John Merriman's class and for Carlos Eire and Jeff Brenzel's Catholic Intellectual History class. I found myself really digging into those courses. And within my first class at Yale, John Merriman’s French Revolution class, I found myself using French that I’d studied in high school. My sister had learned some French in our high school when we went to the same high school. I took French, and I wasn't as committed to it. I liked language somewhat, and I was okay at it. But when I came to Yale, I thought I should try another language. I ended up going back to French by my second semester after using it a little bit my first year in John’s class. I started loving French when I got to French 140 the following year, and we started studying Vichy, as I had done the year prior. I started thinking that I could use my knowledge of French as a utility if I wanted to be a historian, which by my sophomore year I was thinking I did. I needed to have my language skills solid in order to use them as a foundational tool in my historical research. So I started studying French intensely, and I decided I wanted to study abroad. So I went to Nantes, France and studied there for a semester at the University of Nantes. That experience not only kicked up my French abilities, but I was actually able to form some connections with the History department in Nantes and discuss with my professors what the archives were like, how to use them, and how to effectively engage with them. My French education and my historical education are in many ways intimately tied; I could not have done any of the historical things I wanted to without the language. In the same way, I wouldn't have had the drive to learn the language at all if it weren't for history, making it a necessity in many ways. And of course, it becomes self reinforcing; you just eventually learn to love the language, the people, the culture. I did consider majoring in French, but when I decided to do the M.A. program in History, I thought it best to focus on the one program and senior essay. I do not think I would have considered French as a major had I not already committed to history.

IS: Your knowledge of French really was integral to your historical work. Looking to your future, does your thesis lead into your postgraduate work at all?

JB: I would say no in many ways. I am currently pursuing my M.Ed. at the University of Arizona, in order to become a high school history teacher. The insights I found as I wrote my thesis expand out to general themes of anti-racism, anti-sexism, and anti-conformity, which I bring to the center of my classroom. So, in some sense, my research definitely informs who I am as a teacher. I want to continue the research; the research isn't over. As I said before, I need to go to the archives in Algeria before anything and build from Dr. Nina Studer’s works. If I ever visit France, I will definitely stop by the archives. I do plan to continue my research during the summers, but time will tell what I am able to produce.

IS: What would you say was your favorite part of being a history major at Yale? You mention John Merriman’s clases a great deal, but I was wondering if there were any other highlights.

JB: Firstly, I have to give a huge thank you to Professor Merriman and Professor Carolyn Dean. The most beneficial part was also the most stressful part. I did the B.A./M.A. dual degree program at the same time as this essay, so in my last year, I was essentially taking all masters-level classes. Those were really great. They stretched my mind and my writing abilities to a level that I did not foresee. I thought I was a strong reader; I'd taken these junior seminars and could knock out a book in two days if I needed to. I didn't realize that there was a totally different dimension to graduate-level work. In particular, in Carolyn Dean's class, there were three of us in this class, and it was just sitting there with a book, breaking it down and stretching it out as much as possible. The historiographical knowledge of my classmates and professor changed my entire view of history and philosophy. There was a level of discussion and discourse there that was unlike anything I'd ever had. It was so intellectually satisfying every single day. It was just light bulb after light bulb after light bulb, and when you get those, you're so grateful for them. You remember them forever. What I remember is my whole thesis coming together in that class like dominoes falling down. That kind of class taught me that history doesn't have to be fact and fact and fact. History doesn't have to be 123, even if some historians will tell you that it does, that it does have to be an accurate record of all the things that happen. I'm coming from a not only post-structuralist place but also an intersubjective place, which seeks to make unique the voice of the writer and to not speak on the behalf of others. So, in some ways I'm doing that, and I'm allowing my work to say “this is what I think about it.” You can adopt this view; you can adopt this methodology. You can ignore my conclusions about what I think the effect of absinthe on the twenty-first century discourse of drugs and alcoholism was. But, at the same time, you are getting one view of it, and you're getting one part of the discourse that you can reference. I think that's the strongest way to build knowledge. It's not through the citation of supposedly-objective facts but rather through saying, “Hey, this is what I'm saying. You can agree with it or you can disagree with it, but reckon with the ideas.” I'll even source the original quote that inspired my thoughts. “You'll get something useful if you entertain my epistemology.” I am not trying to treat the subject comprehensively: I am simply trying to provide one way of seeing the issue and add depth to the body of research.

IS: My final question is if you have any advice for prospective history majors at Yale?

JB: The first thing I would recommend is to take classes that interest you. Take mostly seminars. Don’t worry about reading loads; you’ll get through. The key is looking for different ways of viewing history. It's not about different regions’ histories. It's not a difference of German versus American versus Canadian. There are certainly differences, and you'll get way, way more out of the indigenous literature and history courses than you will get out of courses about great men, kings, and state-building (in my personal view). I've taken my fair share of demography classes and great men classes; those courses definitely exist and have their place in the historian’s toolbox. That is not a form of history that's totally disappeared. My advice would be to find the historians and figures at Yale who are onto the right path politically and socially. I wouldn't look at course descriptions; I would look at professors, above all. At the end of the day, you’re really looking for an epistemology because for the rest of your life you can read a book and learn the basis of any subject’s history. What you won't get after you leave college is exposure to all these different ways of thinking about history. It's about gaining as many different perspectives on the same subject as you can, that's going to make you the best historian and the best student and the best thinker. It will make everything you do that much richer; you can look at any text and look at all of its implications from indigenous studies to Science and Technology Studies (STS). I would say just keep reading and keep leaving your comfort zone.