Written by Adrian J. Rivera, JE 20'

Advised by Professor Jay Gitlin

Edited by Lica Porcile, BF 21',

Grace Blaxill, PC 22'

Table of Contents

Introduction

Section 1: Beginnings, 1889 - 1939

Biographical Sketch: 1889 – 1926

London Years: 1926 – 1939

Section 2: Fringe, 1939 – 1951

Tyler Kent, An American Whistleblower, 1939 – 1946

United States v. McWilliams, 1944

Aftermath and American Action, 1945

Section 3: Post-War

Conclusion

Bibliographical Essay

Bibliography

Introduction

On July 1, 1942, Charles Parsons issued the latest edition of the Parsons Information Service.[1] “What is the Parsons Information Service?” he began. “It is a non-professional news service solely instituted by me and issued at my expense for the benefit of relatives and friends who, through ignorance or prejudice, are blinded to the truth, in order that they may learn the facts concerning national affairs undistorted by the administration controlled press, radio, and motion pictures, and with the hope that, when aware of the grave dangers that now threaten their country, they will become aroused to righteous anger, will discard their spirit of slothful indifference, and will join in a jehad or holy alliance to throw each and every one of the traitors to this republic out of office and out of the country.” Parsons wrote not as a citizen of Hitler’s Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, or Stalin’s Soviet Union, but as a citizen of Roosevelt’s America. And Roosevelt, in the eyes of Parsons, was the traitor-in-chief.[2]

Little known in his own time and seldom remembered today, Charles Parsons spent almost thirty years fervently writing about and organizing around various conservative causes. Though the issues on which Parsons would focus changed over the course of his life, the roots of any given problem remained the same: New Dealers, Communists, Jews, and Internationalists were always to blame for the country’s ills. Behind even these groups, however, lay an even greater threat.

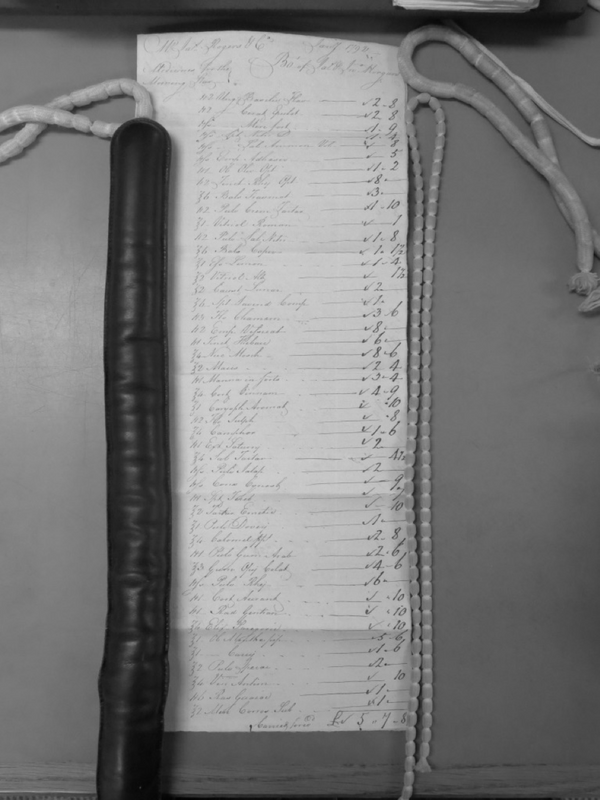

On December 6, 1957 Parsons received a letter from Robert Donner, an industrialist and frequent correspondent of his.[3] “I note that you have known about the ‘Illuminati’ a long time so, of course, you know that it is, or the people behind it are responsible for what is happening to our country and the world today,” Donner wrote, attaching the chart shown in Figure 1.[4]

A few months later, Parsons sent Donner a letter filled with copies of materials in which there were “many confirming facts stated regarding the Illuminati, the Jacobins of France, and some about the French Revolution.”[5] One copy contained the text of Timothy Dwight’s 1798 Fourth of July address, a speech in which Dwight expressed his thoughts on, among other things, the Illuminati: Dwight wrote, “The great and good ends proposed by the Illuminati, as the ultimate objects of their union, are the overthrow of religion, government, and human society civil and domestic.” To Dwight, a Christian minister, President of Yale, and staunch Federalist, any ends involving the overthrow of religion, humane society, and government were neither good and certainly not great.(6) As we will see through a reading of his personal papers, Parsons thought that shadowy, malevolent forces were behind the leading problems of the day, personifying an ideology that would become known as “the paranoid style in American politics.”[6]

This ideology was first described by twentieth-century American historian Richard Hofstadter. Hofstadter referenced the same Timothy Dwight speech when coining the term “the Paranoid Style in American politics” in an essay of the same name appearing in the November 1964 issue of Harper’s Magazine, in which[7] he argued that a “style of mind” defined by a “sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” was an “old and recurrent phenomenon in our public life.” It was this style of mind that constituted “the paranoid style.” [8] Drawing on the anti-Illuminism of Timothy Dwight, the anti-Catholicism of Samuel F. B. Morse, and the anti-Communism of Joseph McCarthy among other examples, Hofstadter would write a book entitled The Paranoid Style whose first essay was an expanded version of the one published in Harper’s and that now examined the candidacy of Barry Goldwater within the context of “the paranoid style.” As we will see, Parsons writings are nothing if not heatedly exaggerated, suspect of many, and conspiratorially fantastical.

Let us return, for a moment, to the exchange between Parsons and Donner. As their letters suggest, the two believed that the French Revolution played a central role in developing many of the elements responsible for the ills of the day. This is the essential intellectual resonance linking Parsons to mainstream conservatism. As Corey Robin has argued in The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump, “many of the characteristics we have come to associate with contemporary conservatism — racism, populism, violence, and a pervasive contempt for custom, convention, law, institutions, and established elites — are not recent or eccentric developments of the American right. They are instead constitutive elements of conservatism, dating back to its origins in the European reaction against the French Revolution.”[98] For Robins and other historians, sociologists, philosophers, and intellectuals in general, the French Revolution represents, and has represented from the time it occurred, a fundamental inversion of the old order, an order based on a hierarchy dating back to the time of Adam and Eve (kings were said to be direct descendants of Adam, for example.)[99] Counterrevolutionaries considered it a theo-cosmic event, so great was the change ushered in by the Revolution.[100] The events of the late eighteenth century ushered in the modern world, and with it, modern conservatism: all forms of it. Regardless of whether one agrees with Robin’s argument that those characteristics are, in fact, associated with contemporary conservatism, Robin’s essential premise is that modern conservatism and its adherents — from Republicans with a capital “r” to the likes of Parsons and his friends, from the conventional conservative to the paranoiac and conspiracist — have roots in 1789. But are those two brands of conservative distinct? Or do they lie on a spectrum that encompasses both, a spectrum that actually allows for one to be both conventional and conspiratorial, for one to hold fringe views while still being able to be in the public eye?

Parsons left behind a body of work that links him to not only the leading provocateurs, ideologues, and conspirators of the day, but to ordinary people and figures in mainstream politics. His oeuvre spans thirty years and consists of hundreds of letters to the editor and thousands of pages of correspondence with conservative colleagues, much of which is riddled with, in the words of Hofstadter, heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy. Parsons personified the paranoid style in American politics, and worked to bring this style into the mainstream.

Because Hofstadter linked Goldwater — a symbol of the more extreme side of American conservatism in the later 20th century — to the paranoid style Parsons personifies, later historians would be quick to dismiss him on the grounds that he wrote off conservatives as little more than “backwards-looking fringe radicals.”[9] Leo Ribuffo, considered a dean of American Conservative historiography, wrote that “Richard Hofstadter’s famous catch phrase, the ‘paranoid style in American politics,’ should be buried with a stake in its heart.”[10] By Ribuffo’s own admission, he tried to do just that.[11] One swing at the stake was his 1983 book The Old Christian Right, a book that examined the lives of Gerald Winrod, William Pelley, and Gerald L.K. Smith, Far-Right Protestants that Hofstadter would have considered emblematic of the paranoid style (Winrod believed that the Illuminati were responsible for the New Deal, and Pelley founded the Silver Legion of America, a white-supremacist, fascist group whose origins were inspired by a mystical vision experienced by Pelley).[12] Ribuffo sought to “understand his subjects rather than merely treat them as target practice.”[13] Rather than view these people and others like them as targets, Ribuffo sought to understand them on their own terms. Where Hofstadter identified the intellectual roots of the paranoid style and sought to enervate their outgrowths — The Paranoid Style is a history but it is also a polemic — Ribuffo was merely interested in describing the far-right elements of the 1930s and 40s. But I fear that in so doing, Ribuffo normalized ordinary people having extreme beliefs, and, more concerningly, extreme people masquerading as proponents of ordinary ideas.

Because Ribuffo’s method was less polemical and more in line with conventional history writings, much of subsequent history focusing on American conservatives or conservatism follows in Ribuffo’s intellectual footsteps. Indeed, Lisa McGirr’s Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right sought to apply Ribuffo’s methodology to groups of people rather than lone individuals.[14] Hers is a grassroots history of the conservative movement. Rather than study iconoclastic ideologues like Smith, Winrod, and Pelley, McGirr focuses on, as just one example, housewives gathered around kitchen tables in Orange County, thinking of ways they could contribute to the Goldwater Campaign, and eventually, conservative causes in general. It is these housewives gathered around kitchen tables, and others like them, that would help lead Ronald Reagan to victory in 1980, who would help inaugurate the age of conservatism in which we find ourselves today. According to these histories, people like Smith, Winrod, Pelley, and Parsons, are anomalies, fringe actors, uncharacteristic of the broader conservative movement. They are worthy of study only in terms of how they fit into the broader context of conservatism, only worthy of study in terms of how they are normal. Therefore, their rantings and ravings are downplayed or ignored. For historians of conservatism coming after Hofstadter, there was a clear dichotomy between “kitchen-table activists'' and political paranoiacs. Even then, however, historians like Ribuffo were hesitant to exile people into the latter category; consequently, Parsons — rescued from the realm of irredeemable extremists — is merely an isolationist, an anti-New Dealer, a conservative of the mid-twentieth century.

This is, of course, an oversimplification of the historiography of twentieth-century American conservatism. But the supposed dichotomy remains: most scholars would box Parsons into either the “paranoid style” category or into the “kitchen table activist” category. And because Hofstadter’s term has fallen out of fashion, Parsons would likely be studied only in terms of his conventional beliefs and behavior. Most academics, were they to acknowledge him at all, would attempt to fit Parsons into a framework that views even the most outlandish figures of the Right as part and parcel of more conventional conservative politics.

But to do so would be a mistake. In 2011, Kim Phillips Fein, noted historian of American conservatism, released an essay entitled “Conservatism: A State of the Field.”[15] In it, she lauded the move toward studying so called “kitchen table activists” because it expanded the scope of study; scholarship on conservatism in the last thirty years has flourished because it has been able to encompass more people. But, she adds, “there is a tendency to normalize the political world view of the Right, to treat even its most outlandish and radical ideas with patience. Scholars have, at times, felt the need to make the argument that conservatives are just ordinary citizens who happen to hold ideas that are different from those of liberals or leftists.” “Historians who write about the Right,” she continues, “should find ways to do so with a sense of the dignity of their subjects, but they should not hesitate to keep an eye out for the bizarre, the unusual, or the unsettling.” It is only by doing so that we will elucidate what Phillips-Fein identifies as one of the most serious problems historians face today when thinking about the Right: its origins.[16]

Parsons and his life serve as a near perfect synthesis of two major schools of thought concerned with modern American conservatism. He was not only a force unto himself, but a colleague of many other paranoiacs and mainstream Republican political players. When not working in tandem with fringe writers, radio personalities, publishers, and Republican Congressmen, Parsons worked to influence the everyday American’s politics by writing searing invectives, distributing conspiracy-filled mail, and organizing like-minded, disaffected operators. For these reasons, Parsons’s life, and the lives of his conservative compatriots, deserves study. His life offers insights into the origins of modern American conservatism, origins that have been forgotten — willfully or otherwise. He proves that ordinary people with extreme beliefs and extreme people with ordinary appearances are one and the same.

This paper will be divided into three major sections. Section one, “Beginnings,” will offer a general overview of Parson’s biography from 1889 up until 1939 along with brief remarks on how the events described — and his involvement with them — may have affected his ideological framework. Section two — “Fringe” — will examine Parsons as a paranoiac, rage-filled conspiracist, prolific writer, and friend of fascists, anti-Semites, and seditionists. It will do so by examining Parsons’s involvement in three events: the arrest and imprisonment of Tyler Kent; the sedition trial of 1944; and the development of American Action Inc., events that, like Parsons, do not hold places of prominence in American memory. Section three — “Postwar” — will study Parsons as an ordinary man, an avuncular patron of the arts who nevertheless continued to proselytize to anybody who would listen. Altogether, this paper will consider the overlap between the paranoid and the ordinary, the conspiratorial and the quotidian, the conservative and the reactionary, an overlap not as distinct as one might wish, and one that offers insight into the origins and legacies of conservatism as we know it today.

Section 1: Beginnings: 1889 – 1939

Biographical Sketch: 1889 – 1926

Born into privilege, Parsons would face significant tragedy throughout the early part of his life. While his personal papers reveal little about how he conceived of his early years, and a retroactive psychological analysis can only ever be speculative, it is hard not to wonder what the effect of these personal tragedies had on Parsons’s future personality and ideology.

*

Charles Parsons Jr. and Frances Louise Parsons married in the late 19th century. Parsons Jr. was a Yale graduate of the class of 1878 and attended Columbia College Law School, but not before making a fortune as an administrator of major railroad companies. He eventually opened his own firm — Charles Parsons and Company, Brokers — and started a family.[17] Their daughter Winifred was born on July 26, 1884 and their first son, Charles, was born on May 31, 1889.[18] A second son, Henry, was born on May 15, 1890.[19]

Alas, the parents of Charles III died young: France Louise in 1896 and Charles Jr. in 1889, leaving their three children in the care of a relative.[20] The two boys were sent to the Pomfret School, a private boarding school in central Connecticut; Winifred died in 1908, the same year that Charles started at Yale and a year before Henry started at Yale.[21]Before they were 20, the two brothers had lost three of their immediate family members.

Charles ran on the Freshman Track team, was on the governing board of the Yacht Club, and would join Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE), then a fraternity for the upper-crust scions of the Northeast; judging from a card bearing the DKE insignia, then, as now, secretive initiation rites necessarily accompanied access to exclusive clubs: “Arrive at the meeting place tonight at 11:30. Do not be late. Bring a towel.”[22] In the spring of his junior year, Charles would be tapped by Scroll and Key, one of Yale’s oldest and most powerful secret societies.[23] A year later, on the eve of graduation, “Parsons’ future occupation [was] undecided.”[24] In practice, Parsons would spend the next few years trying his hand at various occupations, none of which he stuck with for very long: he had a stint at a railroad company loading freight, he helped set up a mining operation with some friends in the eastern part of Death Valley, and he even joined New York City’s Squadron A Cavalry unit, a united deployed to the Texas-Mexico border to defend against potential attacks from Pancho Villa.[25] About a year later, in 1917, Parsons enlisted in the army to aid the American forces in the First World War. He served with the 153rd Depot Brigade until the war’s end.[26]

In the meantime, two significant developments took place in Parsons’s personal life. First, while traveling through Europe in the time between graduation and his serving with Squadron A, Parsons met Mary Elizabeth Curry, the love of his life. Originally meeting onboard the RMS Lusitania, the two wouldn’t marry until 1918, just a few months short of the close of the war.[27]

Second, Henry — Charles’s younger brother — would follow a path that ran parallel to his elder brother’s. He was a member of the Elizabethan Club and the Yacht Club, he was a part of the Dramatic Association, and graduated with honors in English, a subject in which he was able to graduate with both a Bachelor and Master of Arts. He, too, was a part of Scroll and Key, alongside a good friend and roommate, Cole Porter. Then, he went off to Oxford for a yearlong fellowship at Balliol College. When he returned to the U.S. in 1914, he began his legal education at Harvard Law School. World War I interrupted his studies, of course, when he volunteered to join an ambulance unit. Eventually, he was granted a First Lieutenant’s commission and helped to command the Echelon American Parcs A and C on the front lines in France. In 1917, his service would earn him a Croix de Guerre and the right to wear the hat of the Chausseurs d’Alpins, an elite mountain infantry unit in the French Army. He was the first American to win such an honor. In 1918, his service also earned him an evacuation from the front in the face of a bout of pneumonia. While recovering from that illness, he developed an abscess in his leg, from which, the Obituary Record tells us, “he barely recovered.” Henry returned home in 1919 and landed a job with the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland in New York City. He’d work there until June 17th, 1920, when on that date “he shot and killed himself.” “It is thought,” the Obituary Record reports, “that he may have been suffering from shell shock at the time.” What was then shell shock is now considered post-traumatic stress disorder, of course.[28]

After his brother’s suicide, Charles began a new chapter of his life. He and Elizabeth Curry gave birth to Mary Curry Parsons just a month before Henry’s death. At the time, Parsons was working in the burgeoning motion picture industry in Dallas, Texas, but by 1921, the office for which he worked had shut down. According to the Finding Aid, this was the last time Parsons would be employed — at least, in any normal capacity.[29]

Tragedy struck yet again in 1925 when Mary Curry was just about to turn five years old. Elizabeth Curry died on March 29, 1925, leaving Charles to raise his daughter alone. By the time he was thirty-six years old, Parsons had lost his mother, his father, his brother, his sister, and his wife. It is small wonder that he fled with Mary Curry to London in 1926. They would live there until the outbreak of World War II in 1939.[30]

London Years: 1926 – 1939

Parsons was able to live off of the enormous wealth he inherited from his parents. He spent his time in London working as a book collector and cavorting with writer and literary types, chief among them James Branch Cabell and Arthur Machen. While it is fundamentally unclear what drew Parsons to the two authors, it must be considered that the nature of their writings — fantastical, otherworldly, and premised on the idea that there were forces at work beyond what met the eye — influenced Parsons’ own worldview. At the very least, Parsons’ fascination with the work speaks to his proclivities for the extraordinary, the outlandish and the mysterious.

*

Not well remembered today, James Branch Cabell was, at one time, among the most famous writers of the 1920s, ranking among those like H.L. Mencken and Sinclair Lewis.[31] Cabell wrote what was then called “Escapist” fiction, or what would today be called fantasy. His most famous novel was entitled Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice.[32] The story was set in Poictesme, a mythical world of Cabell’s creation in which he set several of his books. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the book “chronicles the adventures of a pawnbroker named Jurgen who, motivated by guilt and gossip, sets off reluctantly in search of Dame Lisa, his loquacious nagging wife who has been abducted by the Devil. Along the way, Jurgen encounters Dorothy, the love of his youth, who does not recognize him. Through the power granted him by the earth goddess, he relives one day with Dorothy. Jurgen and legendary women such as Guinevere share erotic experiences, but he is ultimately reunited with his wife.”[33] “Veracity,” Cabell once wrote, “is the one unpardonable sin, not merely against art, but against human welfare.”[34] Such a quotation speaks to Cabell’s own worldview, of course, but could just as easily apply to Parsons’ own way of thinking: for Parsons, “veracity” was something that needed to be uncovered rather than passively perceived. There was always some greater truth to be had.

On February 12th, 1945, for example, Parsons sent several bulletins to his friend Clifford Ahlers, a California rancher. “President Roosevelt,” he wrote, “flatters, decorates, and promotes the generals and admirals and they back up all his traitorous schemes to enslave the public and destroy the nation through war. The generals and admirals don’t want the war to stop just as FDR doesn’t want it to stop.” Rather than align himself with the general consensus — that the Roosevelt administration wanted to win the war as soon as possible — Parsons took the heterodox view, to put it lightly, that the administration was actually working to prolong the war in the name of enslaving and destroying the American public. This was the truth for Parsons, and he actively worked to communicate it.

Parsons’ other friend, Arthur Machen, wrote books of a similar kind. Known to at least one modern writer as “the forgotten father of weird fiction,” Machen influenced and paved the way for horror writers like H.P. Lovecraft and Stephen King; indeed, King called Machen’s most well-known story The Great God Pan “one of the best horror stories ever written. Maybe the best in the English language.”[35] The premise of the novella is that a brain surgeon seeks to operate on his patient to give her a glimpse of the pagan god Pan, the god of the wild. The doctor, an expert in “transcendental medicine,” as he calls it, wants to reveal the reality of the world we see before us, wants to highlight that there is more to the world than the truth offered by science and reason.[36] Machen was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society dedicated to the occult. Fellow members included W.B. Yeats and Aleister Crowley, the occultist and alleged Satanist.[37] “Every branch of human knowledge, if traced up to its source and final principles, vanishes into mystery” Machen once wrote.[38] The quotation, taken to its logical conclusion, implicitly asks if there is a truth to be had at all. Such epistemological uncertainty appears to be at the heart of every conspiracy theory — for who is really to say what is beyond the realm of possibility and what is not — and would, whether consciously or otherwise, play an important part in Parsons later life.

Parsons was a big fan of the two authors, believing that the world needed to listen to the message they sought to spread. Years later, he would contribute to that very cause. “Since the autumn of 1939, Mr. Charles Parsons, B.A. 1912, has been presenting the University Library with his collections of recent English and American novelists,” read a press release issued by the Yale University Library. “These are a most welcome gift. Few libraries are able to concentrate on modern writers the attention an intelligent collector gives to his books, and as Mr. Parsons has worked with knowledge and enthusiasm in his chosen field, the Yale Library has been greatly benefitted in a new and essential direction.” He donated 193 volumes of Machen’s and 216 of Cabell’s, in addition to biographies, bibliographies, criticism, and periodicals relating to the two men. All remain in the possession of the library to this day and are accessible to students and researchers alike.[39]

But Parsons didn’t just make friends with writers and mystics. Sometime in the 14-year period in which Parsons lived in London, Parsons made the acquaintance of a man named Tyler Kent, a code clerk at the American Embassy in London. It would be the story of Tyler Kent — and Parsons’ role in it — that would lead Machen to remark in 1943, “It would be a good thing for Parsons if he got laid by the heels & given the solitude and opportunity for reflection that a cell affords. There was always something queer about him,” Machen concludes, “and he has certainly been getting queerer, in a very unpleasant fashion.”[40] For these authors obsessed with the odd, Parsons had become too odd even for them.

Section 2: Fringe: 1939 – 1951

For the last twenty-six years of his life, Parsons spent much of his time writing and organizing around various issues. The vast majority of the Charles Parsons Collection consists of received mail. Few outgoing letters survive within this particular archive. But when considering what does survive — and when considering what Parsons must have had to have written to warrant some of the responses that he received — we see that though the specific object of his and his colleagues’ ire would change over the years, the voice of his op-eds, personal correspondence, and their writings in general, would remain the same. Often angry, accusatory, and self-righteous, Parsons’s prose and that of his friends’ offers a glimpse into the hatred they felt toward anyone and anything that they considered an enemy. Friends who floated the idea of breaking ranks even slightly were subject to the strictest scrutiny. Writing in 1945 to E. M. Biggers, a Texas publisher of anti-New Deal propaganda and a long-time Parsons pen-pal, Parsons condemned Biggers after he suggested that he might align himself with Arthur Vandeburg, a Republican Senator who, initially against Roosevelt and the New Deal, came to support Roosevelt’s foreign policy: “I neither agree with nor comprehend your political reasoning. You say that if Senator Vandeburg adopts New Deal ideas, ‘I shall accept it as necessary evil we must go along with, for I have great faith in Vandeburg.’ I do not respect any such immoral reasoning as that. Because a man you have respected suddenly stultifies himself and renounces his life long convictions to serve the devil (in the person of Franklin D. Roosevelt) for personal profit, you feel you must go along with him. By renouncing Americanism and embracing internationalism, Vandeburg has read himself out of the Republican party and branded himself as a TRAITOR.” (Need footnote) For Parsons and his allies, the hatred that they felt and with which they wrote was a means to an end, a kindling that fueled the fiery fight against an administration — and its legacy — that was, according to them, fundamentally antithetical to what they believed to be the American interest. That was, as the above quotations suggestions, Satanic.

*

Tyler Kent, An American Whistleblower: 1939 – 1946

Parsons’ participation in the defense of Tyler Kent — a man among the first “whistleblowers” in 20th century American history — offers insights into Parsons’ approach toward the world. Whether the controversies surrounding Kent helped to solidify Parsons’ already isolationist worldview or whether Parsons’ already isolationist worldview drove him to intervene in the case of Tyler Kent, one thing is certain: his activities surrounding the affair marked his first known foray into politics, and would eventually propel him into a network of anti-Semites, seditionists, and fascists.

*

Late morning, Monday, May 20th, 1940. Tyler Kent, an American code clerk at the American Embassy in London, was just a few minutes from Hyde Park in his apartment on Gloucester Place. Four Scotland Yard detectives broke the Monday morning peace, however, when they broke down the door to Kent’s apartment. Bearing a search warrant for documents that Kent had allegedly stolen from the American Embassy, the detectives found what they were looking for: 1,500 confidential cables dealing with American diplomacy, all kept under the mere security of Kent’s locked apartment door. Kent was arrested for violating the British Official Secrets Act, but of course, he believed his actions to have been warranted. After all, Kent thought that he was exposing a conspiracy concocted by President Roosevelt and, at the time the “conspiracy” began, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill. Their alleged plot? To negotiate a plan that would bring America into the war on the side of Britain, a plan contradictory to Roosevelt’s promises to keep the country out of war. [41] It was a scheme that, in Parsons’ eyes, confirmed Roosevelt’s interventionist and internationalist tendencies. And according to Parsons, “Internationalism [was] TREASON to the United States.”[42]

But what was the exact nature of the correspondence between Roosevelt and Churchill? As is the case with almost every conspiracy theory, a grain of truth lay at the center of Kent’s case against the two leaders. Here are the facts we know today: Roosevelt and Churchill had exchanged secret letters, but where Kent initially said that the letters numbered in the thousands, eventually revising the number down to around a hundred, there were, in reality, only fifteen. Kent had eight of them in his apartment. Kent had argued that he stole the documents because he “considered that their contents [were] concrete proof of non-neutral activity on the part of Roosevelt and co.” Roosevelt and Churchill had discussed the affairs of the day, which obviously encompassed the war, but according to the historians Warren Kimball and Bruce Bartlett, the authors of one of the only serious accounts of this entire episode, “Neither all fifteen Roosevelt-Churchill messages nor all the other documents found in Kent's apartment contained anything to substantiate [Kent’s] charge.” Indeed, “there was nothing about Churchill planning to replace Chamberlain as prime minister, nothing to suggest firm promises to aid England in any secret, illegal way...there was no promise of American intervention by the U.S. ambassador in France, William Bullitt, and no word of any plan by Roosevelt to circumvent Congress and provide aid to Britain. In fact, the president told Churchill that any transfer of destroyers would have to be approved by Congress.”[43]The very last point directly contradicts the charge that Roosevelt was unilaterally attempting to bring America into the war, that he was attempting to subvert the authority of the legislative branch — he was doing just the opposite.[44] In short, Kent’s charge of conspiracy on the part of Churchill and Roosevelt was almost entirely unfounded. Yes the two had discussed the war, but there was no talk of America entering the war, there was no discussion of the Lend-Lease Bill, and there was nothing to indicate that Roosevelt wanted to go to war. If one wonders why the two leaders were discussing the war in the first place, Roosevelt must have considered the possibility that America would be drawn into war, but that is very different from Roosevelt wanting war, as Parsons alleged: “...I charge, without fear of contradiction, that the late unlamented incumbent of the White House plotted with Winston Churchill to put this country into war, six months before he campaigned for election to a third term on the promise to keep us out of war.”[45] One imagines that these were the exact accusations that Roosevelt and Churchill wanted to avoid by keeping their correspondence secret. But in trying to avoid accusations of an unholy preemptive alliance between America and Britain, the two leaders made themselves vulnerable to that very accusation. It was Kent who laid bare that vulnerability.

And it was Parsons who helped promulgate that accusation. A friend of Kent’s from his days in London, Parsons worked with both Mrs. Ann H. P. Kent, Tyler’s mother, and an anti-war organization called “We, the People, Sovereign” over the course of several years to secure Kent’s release, confirm his innocence, and prove Roosevelt’s guilt. While they largely failed at each of these goals, the documents surrounding their organizing reveal strong connections between anti-Roosevelt sentiment, anti-Semitism, and conspiracy theorizing. In the case of Tyler Kent, paranoia met political organizing.

Though Parsons “spent the better of [his] time to preserve this Republic from those who wish to destroy it,” he could not preserve the Republic on his own.[46] That is where the help of organizations like “We, the People, Sovereign” came in. The organization was led by Kenneth Dent Magruder, a former leader of an America First Committee chapter in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The America First Committee was a national anti-war organization committed to advocating for non-intervention in World War II.[47] America First-ers had various principles behind their preferences for neutrality. Charles Lindbergh, for example, was a prominent spokesman for the Committee as well as a Nazi-sympathizer.[48] Other members of the AFC, including Kingman Brewster, future President of Yale, Potter Stewart, future Supreme Court Justice, and Gerald Ford, future U.S. President, were simply anti-war.[49] The Committee, at one point boasting almost a million members, disbanded in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor.[50] Some former members whole-heartedly embraced the war effort. Others were, to put it generously, slow to abandon their previously held beliefs. Kenneth Magruder was one such person. Working hand in hand, Parsons and Magruder would work to create a network on par with what America First once had.[51]

Parsons initially operated without the support of Magruder and his organization, but his efforts in his home state of Maine were so successful that Magruder offered him the Chairmanship of the American Justice for Tyler Kent Committee and the Vice-Presidency of Magruder’s own organization. “We, the People, Sovereign” wanted Parsons working with them at the national level in as many capacities as possible.[52] He turned down both positions, but refocused his efforts anyway.[53] Lobbying Republican leaders for more information about Kent’s arrest and imprisonment in England, Parsons was a point person for anyone interested in the case of Tyler Kent, including Kent’s mother. “Dear Mr. Parsons,” wrote Mrs. Kent on September 1, 1944, “Thank you for your kind letter of August 29th with the names of the members of Congress whom you so kindly saw on your recent trip to town...Rep. Mundt is in England now, according to the newspapers. He has always been most sympathetic. Do you think some prominent Republicans might cable him: ‘Bring news of Kent if possible.’?”[54] Because Kent had been tried in camera away from the prying eyes of the press, precious little was known about the entire affair. This fact added mystery and intrigue to a case already rife with secrecy and unanswered questions.

Roosevelt detractors capitalized on the mystery and intrigue surrounding another major moment from just a few years before: The attack on Pearl Harbor. Mary Howard Hoopes, a pamphleteer and contemporary of Parsons from California, wrote him a letter on October 2, 1944 to express her thoughts on the best strategy moving forward: “I think our VERY best chance for Tyler Kent IS to link the cases together with the strong chain of constitutional rights. The public have had almost three years to think over the tragedy of Pearl Harbor but such silence and secrecy has surrounded the case of Tyler Kent that they may not have had time to properly ‘digest’ all that it implies.”[55] It is unclear if Parsons already had suspicions about the attack on Pearl Harbor or the Kent Case led him to believe that similar treachery had been at work in the Pearl Harbor attack, but in any event, Parsons took Hoopes’s advice. The events leading up to both events shared the most superficial of similarities, but that was enough for Parsons. Roosevelt’s alleged failure to prevent the attack was, in Parsons’s book, yet another pretext to expel him from the presidency.[56]

In the wake of the events of December 7, 1941, some Americans wondered how such an attack could have occurred completely by surprise; others wondered why such a significant portion of the American fleet had been stationed in one place.[57] These questions, among others, came up in a book entitled The Truth about Pearl Harbor by John T. Flynn. Beyond questions, however, the book provided answers. And Flynn’s answer to the most fundamental question of the day — why did the attacks happen — was that the attacks happened because they were allowed to happen. Flynn alleged that Roosevelt deliberately allowed the attacked to happen, that he had, in fact, wanted the attacks to happen, so that he would have an excuse to bring America into the war.[58] Coincidentally, Flynn was a cofounder of the American First Committee, a friend of “We, the People, Sovereign,” and Charles Parsons. The questions and hypotheses surrounding the Pearl Harbor attacks, and the voices behind them, drew enough attention to the Pearl Harbor conspiracy theory that Congress was forced to hold hearings regarding the apparent intelligence failures of the U.S. Parsons, “We, the People Sovereign,” and Mary Edward Hoopes wanted to achieve something similar with the Kent case.

But to what end? Parsons and his colleagues certainly wanted Kent to be released, but they wanted, too, to use this entire affair as an opportunity to expose Roosevelt and his treachery. 1944 was an election year, after all, and Roosevelt and his administration had been in power for fourteen years by that point. As Mary Hoopes noted in her October 2 letter, “We certainly need the biggest ‘house cleaning’ this country has ever had.”[59] She went on to praise the presidential potential of Thomas Dewey, the Republican nominee for president, hoping he would be able to bring together a country desperately in need of unity. “The Dark Forces of disintegration have taken a pretty heavy toll I feel with our national life and honor.” Hoopes’ use of the phrase “Dark Forces” brings forth associations of evil and secrecy, makes it seem as though there is something out there arrayed against her and her fellow Americans. But what could those “Dark Forces” be?

The Roosevelt Administration was certainly, in the eyes of Parsons and his contemporaries, one such force. On September 2, 1944, the State department released a 2000-word statement outlining the circumstances of Kent’s arrest. It described Kent’s involvement in “a group of persons suspected of conducting pro-German activities under the cloak of anti-Jewish propaganda.” Later, Kenneth Magruder, Parsons’ friend and co-worker in “We, the People, Sovereign”, would lament the “smear” of being labelled anti-Semitic.[60] In any event, being a part of an anti-Semitic group was not illegal on its own. But the statement added that “prominent in this group was Anna Wolkoff,” a White Russian émigré. “After the outbreak of the present war,” the statement continued, “the British police had become interested in Miss Wolkoff’s activities, believing that she was in sympathy with certain of Germany’s objectives, that she and some of her associates were hostile to Britain’s war effort, that she was involved with pro-German propaganda, that she had a channel of communication with Germany and that she was making use of that channel of communication.” The statement went on to characterize Wolkoff as “having been in frequent contact with Kent.”[61] Decades later, after the release and declassification of documents related to the matter, historians would learn that Wolkoff was passing along information to Germany via a third-party, and that this information had, wittingly or otherwise, been provided by Kent.[62] In the moment, however, guilt by association and the thought that classified documents could fall into pro-German hands was enough to earn Scotland Yard a warrant, and enough to convince the American Ambassador to England, Joseph P. Kennedy, to waive Kent’s diplomatic immunity. The conspiracy theorists had their explanation.

The statement satisfied neither the conspiracy theorists nor Kent’s mother, as evidenced by a letter she and the American Justice for Tyler Kent Committee sent to Secretary of State Cordell Hull: “...the long release by the State Department on September the 2nd relative to Tyler Kent, left completely unanswered the point on which the American people demand an answer, i.e., the existence or non-existence of secret pre-war agreements made by the President of the United States without ‘the advice and consent of the senate.’”[63] Almost certainly at the direction, implicit or otherwise, of Parsons and “We, the People, Sovereign,” the individual case of Tyler Kent’s indiscretions was now being conflated with whether or not, in effect, Roosevelt had committed an impeachable offense, just as had happened with the events of Pearl Harbor. “Very few persons beside his mother are interested in Tyler Kent per se,” Mrs. Kent continued, “but one hundred and thirty odd million Americans are vitally concerned to learn whether it is true that in a time of peace, one year before the Lend-Lease bill and other measures were put before the Senate, they had been planned ‘between the American president and the British navy head.’”[64] Roosevelt and Churchill, in their quest to avoid indications to the contrary, had brought on the appearance of impropriety, adding to the laundry list of reasons their detractors had to despise them. Even though their claims would be disproven, the conspiracists had planted their seeds of doubt, if not in the minds of Americans at large, then in their own minds at the very least.

The conspiracists did, however, seek to nurture those seeds of doubt in the minds of as many Americans as they could. They tried to convince ordinary people. On June 21, 1945, one of these ordinary people, a Ms. Maude DeLand, wrote to Parsons to express her concern that “Congress investigate and find out the contents of the cables which passed between Roosevelt and Churchill, so that the people could know if Roosevelt was planning with Churchill to get this country into war at the same time that he was assuring the American people ‘again and again and again’ that our boys would not be sent into a foreign war.”[65] Under the orthodox historical perception of conservatives, DeLand’s concern is perfectly normal, especially considering that, at the time, the contents of those letters were not known to the general public. But DeLand concludes with the following: “The Executive branch controls the Legislative branch through his patronage distributing power, and controls the Judicial branch through his appointment of the federal judges and the judges of the Supreme Court. I would rather have a totalitarian state frankly proclaimed than to talk of freedom and achieve totalitarianism through hypocrisy and stealth.”[66] To criticize the secrecy that surrounded the Roosevelt-Churchill exchange is one thing, but to compare it to totalitarianism? Again, we see the focus on the existence of a deeper truth hidden behind ordinary political life, and again, we see ordinary political means propagating paranoid-style politics to excavate that deeper truth.

Moving from their abstract conceptions of totalitarianism to accusations of assassination, successful and attempted, the conspiracists inched further and further toward the pale. On the day that Kent returned to the United States, for example, Parsons wanted to serve as Kent’s bodyguard: “I informed Mrs. Kent that you [Charles] would like to be Tyler’s bodyguard.”[67] Why did Parsons think Kent needed a bodyguard? It is unclear when exactly he did so, but sometime before Kent’s return, Parsons copied by hand an article from the Sunday, January 3rd, 1943 edition of The New York Times.[68] The article detailed the death of John Bryan, grandson of William Jennings Bryan, and friend of Tyler Kent. The two had met while they had been imprisoned on the Isle of Wight. According to the Times, authorities initially suspected foul play in Bryan’s death. “Because of bruises on his head and face and fresh blood, Detective John Maguire listed the death as suspicious and an immediate autopsy was performed,” the paper continued. “This showed, however, that the bruises were sustained some time ago and Assistant Medical Examiner Milton Helpern, who performed the autopsy, announced that the death was due to natural causes and listed the specific cause as “general congestion of the viscera.” Bryan was 38 years old at the time of his death. Robert Lehman, of Lehman Brothers fame, identified the body; Bryan had been his brother-in-law.[69]

That meant, of course, as John Howland Snow pointed out in The Case of Tyler Kent, a non-peer reviewed account of Kent’s story, that Mrs. Robert Lehman was involved.[70] And “Mrs. Robert Lehman, of New York’s Park Avenue, sister of the deceased, was the wife of the late adopted son of former Governor Herbert Lehman of New York. Ex-Governor Lehman is presently Director General of U.N.R.R.A. [United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration], that international body about which there has been, is, and will be, such violent discussions both in and out of congress.”[71] Reading between the lines of this this seemingly innocuous paragraph, resonances that Parsons, and others like him, would have picked up on, become clear.

First, Lehman was a Jewish person in the banking industry, a fact that Parsons used to bolster his image of the stereotypical Jewish banker. Next, a relative of Lehman’s was involved with the United Nations, an “internationalist” organization if there ever was one, an organization that Parsons would eventually label as a Communist front, a front that, in Parsons eyes, was organized by “the Jews.”[72] Finally, the U.N.R.R.A. helped relocate tens of thousands of Holocaust survivors.[73] Parsons was a close correspondent of Harry Elmer Barnes, a prominent American historian in the 20thcentury, and a Holocaust revisionist — while there’s no explicit mention of Parsons being a Holocaust denier, one must wonder what he found so compelling in Barnes’ revisionism, must wonder what led him to secure Barnes’ trust to the extent that Barnes entrusted him with an unpublished manuscript.[74]

The plot thickened: just above the information regarding Mr. and Mrs. Robert Lehman stood the following lines: “On July 20th, 1944, the [N.Y. Journal-American] carried an interview with Upton Close, famous commentator and historian. The dead man, Close is directly quoted, ‘did some talking about the Kent case around town, apparently trying to get it printed, but everybody was afraid of him...(and) before he could be brought to Washington he was found dead on January 2 (3), 1943.’”[75] Parsons copied by hand The New York Times article, was fascinated with Bryan’s death, believed that Kent needed a bodyguard because of the information Close had peddled. Information peddling was something Close had done for a while. Upton Close, also known as Josef Hall, was a foreign correspondent in Asia who, upon returning home, because a “nationalist” armed with the power of a radio show and a newsletter entitled Closer-Ups.[76] Close was a peddler of the Pearl Harbor conspiracy, too, and became a frequent correspondent of Parsons. Indeed, when Parsons wrote a treatise on the Pearl Harbor attacks, “Upton [liked it] very much,” according to Close’s secretary. Close liked it so much that he wanted to know if Parsons had “mimeographed a quantity for sale...so [Close] could give them a plug in some newsletter when he [had] the space to do so.”[77] So as it concerned the alleged murder of Bryan at the hands of some unknown entity, an entity that wanted to retain the secrecy surrounding the Kent Case, Parsons trusted Close’s information. If such a thing could happen to Bryan, the same thing could happen to Kent.

But nothing of the sort happened to Kent. He returned to the United States, got married, squandered his wife’s fortune, and lived out the rest of his life in relative obscurity. He became a vocal anti-Semite and conspiracy theorist, although his anti-Semitism was present even at the time of his arrest in the 40s.[78]

Anti-Semitism was a theme within the Tyler Kent narrative. From Kent to Magruder to Parsons, all exhibited a hatred of Jewish people. One might write this off as merely the spirit of the era, but the extent of their hatred was extraordinary even for the time. For example, on March 30, 1945, Magruder wrote to Parsons that “On this Good Friday, I’ll continue my tale where I left off last night, though I am feeling pretty depressed by news that one Hyman, not an Irishman, has bought the apartment house where my mother and I have been living since the building was completed in 1929. The new owner shows immediately the usual characteristics. Squirrel Hill has been one of the best districts of Pittsburgh, and our apartment house has been admired as exceptionally fine...however, the plague of “refugees” had swept over this area, converting Squirrel Hill into ‘Kike’s Peak’...”[79] “Hyman” refers to the Jewish first name “Hyman” or “Chaim,” and was often altered to the slurs “Hymie” or “Heimy.”[80] We see in this paragraph, too, the conflation of “refugees” and Jewish people. And because the UNRRA is a part of the United Nations, the definition and product of “internationalism,” Parsons would have considered the seemingly innocuous aid organization complicit to a vast Zionist conspiracy. Though it is clear by now that Parsons exhibited some level of anti-Semitism, Magruder basically equates the pair’s hatred when stating the following: “In addition to your fine letter to me, I have enjoyed as usual all your enclosures. It seems to me that you hit the nail on the head every time. I already had Klein’s ‘Frankfurter’ and Dr. Smith’s ‘British Plot’ but certainly can put to good use the extra copies. It is real service for you to be circulating such valuable information. Your views and mine seem to coincide on every point.”[81] Magruder makes it clear: he and Parsons were cut from the same cloth.

But who were Klein and Dr. Smith? Why was Parsons sending copies of their letters to Magruder? The answer lies in a study of the largest sedition trial to ever take place in U.S. history, a trial that brought together some of the most strident reactionaries of the day, reactionaries with whom Parsons was well acquainted. In the wake of the Kent case, it was with this collection of anti-Semites, fascists, and Nazi sympathizers with whom Parsons would align himself.

United States v. McWilliams, 1944

Around the same time Parsons was involved in the Tyler Kent case, he was corresponding with defendants and lawyers in United States v. McWilliams. Largely forgotten or written off as an abuse of civil liberties on the part of the Roosevelt administration, McWilliams stands as the largest sedition trial in U.S. history: thirty pamphleteers, columnists, radio hosts, newsletter writers, and organizers were charged with violating the Smith Act.[82] The Smith Act, passed in 1940, “made it a criminal offense to advocate the violent overthrow of the government or to organize or be a member of any group or society devoted to such advocacy.”[83] Though the act was initially — and successfully — used against socialists and communists, Roosevelt eventually directed the Attorney General, Francis Biddle, to turn the Department of Justice’s attention toward right-wing extremists.[84] “When are you going to indict the seditionists?” he is reported to have asked Biddle.[85] And so the Attorney General and Department of Justice turned their eye toward prominent anti-Semites, Nazi-sympathizers, and self-proclaimed fascists in the summer of 1942, when the first grand jury indictments came through for the case that would eventually turn into McWilliams. It was with several of these defendants that Parsons would later work to create a “nationalist” organization dedicated to spreading the very ideas for which the defendants were being prosecuted.

*

Among some of those initially indicted was Leon C. de Aryan. Originally born Constantine Lagenopol in Romania, Lagenopol moved to the U.S. and took up a version of Christian mysticism known as Mazdaznan.[86]Mazdaznan held that members of the “Aryan race” were the true inheritors of the earth and that other races would eventually fall by the wayside. Lagenopol would change his name to “de Aryan” in honor of his new religion and become Editor-in-Chief of The Broom, a San Diego newspaper.[87] How Parsons came into contact with The Broom or with de Aryan is uncertain, but Parsons became a columnist for the newspaper, writing for de Aryan throughout the 40s and 50s.[88]

The Broom peddled conspiracies and allegations in line with the paranoid style characteristic of Parsons, de Aryan, and so many of the defendants in the sedition trial. One of the title headings for the January 1, 1951 issue for example, reads “Jewish Vegetarian Propaganda.”[89] The article continued, “Don’t fall for the request of the American Vegetarian Union to register with them as vegetarians. They are a Jew-controlled Sanhedrin handmaiden to catch suckers and well-meaning imbeciles...”[90] The anti-Semitism didn’t just apply to vegetarians. Referring to Herbert Lehman, the relative of the Lehmans allegedly involved in the Bryan murder that so fascinated the Kent conspiracists, de Aryan wrote, “On the closing day of the recent session [in the Senate] Senator Lehman delivered a glowing tribute to Sen. Frank Graham who has just been turned down by the voters of his own party. Nuf sed! (sic). The presence of that kike Lehman in that once honorable and dignified body has degraded it to a new low.”[91]

The anti-Semitism was not just limited to Parsons’ associates. In a letter addressed to Governor of New York Thomas Dewey, the unsuccessful Republican nominee for President in 1944, and reprinted in The Broom, Parsons wrote “Playing for the votes of the internationalist bankers and oil producers, who put their selfish interests above loyalty to their country, you went all out for the damnable United Nations Organization which was conceived by traitors and swallowed by fools. The ‘U.N’ was founded for the purpose of sending American boys to their death in foreign wars that are not, and never have been, any of our affair. This monstrous Tower of Babel was also erected for the purpose of putting over Zionism and Communism, both of which are plots to destroy the Christian World.”[92] The quotation highlights Parsons’s isolationism and anti-Semitism, implicit and otherwise. It calls back to Parsons’s fixation on opposing internationalism, and recycles language used during World War II, e.g. the claim that the war is “not our war.” But the anti-Semitism of The Broom wasn’t just limited to gentile writers.

Yet another frequent writer for The Broom was Henry H. Klein, a lawyer in the McWilliams trial and a Jewish person. On December 25, 1950, Klein condemned the leaders of the then-10 million Jews in the United States in a Broomcolumn entitled “Jews are Victims of their Leaders.”[93] “Judaism is the most lucrative racket on Earth,” Klein wrote. “A large part of the resources of Jews has been drained for ‘protection.’ Jewish leaders keep them scared so that they can continue to drain them. As one Jewish writer expressed it, ‘A frightened Jew is the best contributor.’ It’s about time Jews demanded an accounting of their contributions.”[94] Klein was also the author of A Jew Exposes the Jewish World Conspiracy. In this book and in his Broom columns, Klein drew on his Jewish heritage to make the case against the very people from which he descended.[95]

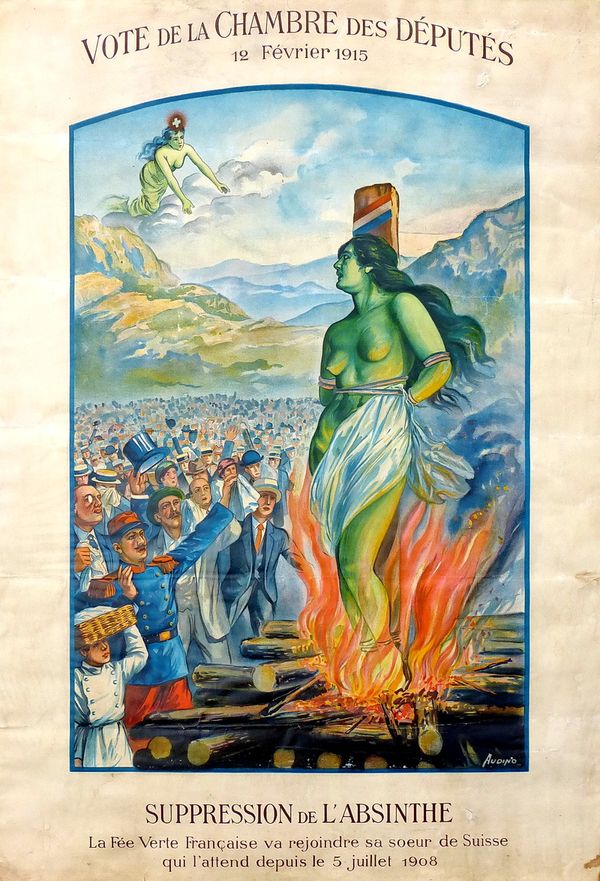

It wasn’t just the defendants who had fringe views in the 1944 sedition trial: Klein was Colonel Eugene N. Sanctuary’s attorney.[96] Sanctuary was one of those indicted for violating the Smith Act. The founder of the American Christian Defenders and author of Are These Things So, Sanctuary was a virulent anti-Semite as well as intensely opposed to Roosevelt. Sanctuary subtitled his book “A Study in Modern Termites of the Homo Sapiens Type,” implicitly referring to Jewish people as pests. The book, Sanctuary wrote, was compiled by the WAAJA, or the World Alliance Against Jewish Aggressiveness. On the next page, Sanctuary dedicated his book to the following, among others: “To the Foes of ‘Aggressiveness’ named on [the] title page,” and “to ‘Constitutionalists’ as opposed to the ‘New Deal,’ inasmuch as some parts of the New Deal can be traced back to the French Revolution of 150 years ago.”[97] The fact that Sanctuary was anti-Semitic is not surprising after having examined some of his associates and their writings. But nevertheless, it is striking that Sanctuary’s alludes to the French Revolution, making yet again explicit the link between paranoid style politics and conservatism.

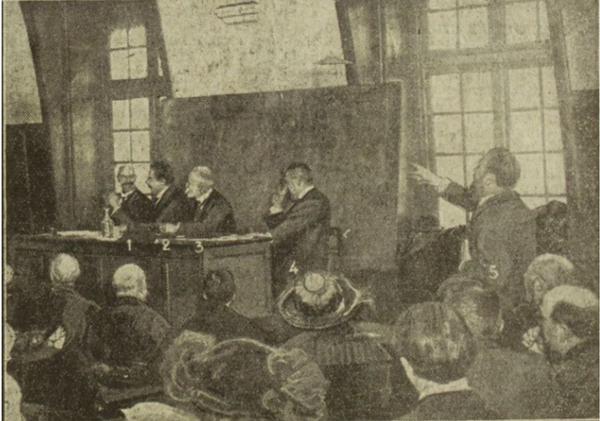

The events of that trial are as follows: beginning on April 17th, 1944, the thirty defendants were called to the D.C. district court.[101] These included Eugene Sanctuary and Joseph E. McWilliams, pictured in Figure 2. McWilliams was the leader of the Christian Mobilizers, a group dedicated to spreading anti-Semitic, fascist, and anti-Roosevelt propaganda.[102]

Lois de Lafayette Washburn, a right-wing propagandist was there, too. She gave a Nazi salute on the steps of the courthouse. Henry H. Klein was there to represent Sanctuary. Other Parsons correspondents were present as well. By this time, de Aryan had been dropped from the list of those indicted, but a similarly prolific right-wing influencer had taken his place. This was Lawrence Dennis, who has been called “the public face of U.S. fascism.”[104] In short, even with de Aryan’s absence, “Seldom have so many wild-eyed, jumpy lunatic fringe characters been assembled in one spot, within speaking, winking, and whispering distance of one another.”[105]

These “fringe characters” caused a ruckus throughout the trial. To give just a few examples, Ribuffo explains that Henry Klein, for example, “moved for postponement until he could secure testimony about the war from Roosevelt, Biddle, and Secretary of State Cordell Hull; Winston Churchill and Rudolph Hess would be helpful too.” Klein also “distributed literature calling for Roosevelt’s impeachment” when on recess. During opening statements, Klein “listed Justice Felix Frankfurter among Jewish Communists and accused Roosevelt of submission to Stalin.” These, along with many other postponement tactics, frivolous objections, and downright absurdities that occurred over the course of the next several months, might have contributed to the presiding judge’s death on November 29, 1944. Or at least, so thought a U.S. senator, as Ribuffo reports: “Solomon himself could not have survived the trial.”[106] In any event, the judge’s death forced a mistrial. The prosecution lost months of work and recent decisions issued by the Supreme Court led chief prosecutor O. John Rogge to wonder about the utility of bringing the charges again. Indeed, Rogge had wondered about the value of bringing the alleged seditionists to trial in the first place.[107] But that is not to say that Rogge doubted their intentions to undermine the Roosevelt administration, the war effort, and the country more broadly. In fact, Rogge’s actions during and after the trial point toward his being a fundamental believer in the fight against American fascism.

The then-youngest graduate of Harvard Law School, Rogge quickly made a name for himself in the Department of Justice. He was promoted to the role of Assistant Attorney General, and shortly after, in 1943, had been directed by Attorney General Biddle to “conduct an investigation of certain people accused of sedition. This led me to a study of international fascism, for the people under investigation were part of an international movement to destroy democracy both here and abroad.” The study of international fascism led him to a fact finding mission in Europe, where he and his team “encountered such a wealth of material that we could not help but collect some facts which appeared to us to be pertinent to the security of the United States, even though not directly connected with the mission.” The facts in question showed that some high-ranking American politicians had been contacted and perhaps influenced by Nazi officials in Germany. Rogge detailed his findings in an eighty-thousand word report, a report that he believed the Attorney General — now Tom Clark, appointed by Harry Truman after Roosevelt’s death in 1945 — would make public. Rogge thought that presenting a study of how Nazi Germany had sought to influence government officials would help the country defend against Soviet influence. “However,” Rogge continued, “when Attorney General Clark saw some of the names mentioned in the report, specifically the name of Burton K. Wheeler, he told me the report would not be made public. Nevertheless, I completed the report.”[108]

Wheeler was an isolationist and a former America First-er. He had voted against the Lend-Lease bill, against increases in the army and navy, and did not vote when the time came to declare war on Germany and Japan.[109] This information would have been known to Rogge and other Americans at the time. But what Rogge did not know was that Attorney General Clark and Senator Wheeler were friends. Wheeler was friends, too, with former Senator Harry S. Truman, who was now the sitting president. As historian Bradley Hart describes in Hitler’s American Friends, when Truman was made aware that Rogge named Wheeler in his report, “the president summoned Clark to the White House and ordered him to fire Rogge. The excuse given was that Rogge had quoted publicly from his own report, which was officially considered secret.”[110] And so Rogge was fired from the Justice department. “The sequence of events is this,” he said in a statement following his dismissal: “On Tuesday, I went on vacation and started making a series of speeches telling the American people about international fascism, the Fascist threat to the democracy, and attempted Nazi penetration into this country. I spared no one, either high or low. On Friday the Attorney General terminated any appointment. This sequence speaks for itself. The country has a crying need for more statesmen and fewer politicians.”[111] In the years following the trial and Rogge’s Germany investigation, the FBI began to surveil him in the name of anti-Communism. Allegations had arisen that Rogge had been working in the interest of the Soviets after he had aligned himself with the progressive causes of the 1950s and 60s.[112] Burton Wheeler, the rest of the Americans named in Rogge’s report, and most of the alleged seditionists, got off relatively scot-free.

This included Lawrence Dennis, who became a frequent correspondent and friend of Parsons. No friend of Rogge, he nevertheless supported him in his quest to release the information that he had found in Germany implicating members of the U.S. government. He saw Clark’s attempted stifling of Rogge as nothing more than political, or so he wrote in a letter to his attorney, Maximilian St. George, that he shared with Parsons: “...Clark does not want the big political smear of some Truman’s supporters like John L. Lewis and Wheeler.”[113] Though some of his codefendants wanted the report suppressed, “Hell, I want it published,” Dennis wrote. “The more Rogge smears big isolationists, the better I like it. Rogge knows his evidence won’t support a charge of conspiracy to cause insubordination, but that it is good smear material against the Tafts, Wheelers and anti-New Dealers. I want the latter to get plenty of the mud I have been getting. When they have had their yellow pusses rubbed in it as much as mine has been, it may penetrate their thick ivory that persecution should unite its victims against persecution and in favor of decency and fair play.” Dennis wanted all factions of the right — the moderates, like Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio, the ardent isolationists like Wheeler, and the pro-business lobby of the Republican party — to unite against perceived persecution at the hands of the liberal order of the day. Toward the end of his letter, Dennis noted that “The American Action crowd should realize that while pink commentators can be given the best periods nightly, their Upton Close can’t be kept on.”[114] Upton Close, of course, had been involved in promulgating the Pearl Harbor conspiracy and was a correspondent of Parsons. But who was the “American Action crowd”?

Aftermath and American Action, 1945

By the time of the sedition trial’s end in 1947, Parson had developed relationships, both professional and personal, with several of the trial’s defendants and their lawyers. The alleged seditionists were connected to a network of more palatable, but not necessarily any less extreme, conservative conspiracists and crusaders. Parsons, if not already connected to this network, would soon join them and their mission. This event is representative of a larger phenomenon of so-called “crackpots” working with business and political leaders in the name of achieving mutually desired ends.

*

In December of 1946, Dennis passed along to Parsons another one of his letters to Maximilian St. George. He discusses the trial and the financial recompense he hopes to receive after being the “victim” of the government, but he then returns to the subject of Upton Close, who, after a brief period of being off-air, had found a new station. Dennis and his co-defendants received a special shout-out from Close. “And this brings me to express to you my enthusiastic praise and gratitude for the full five minutes Close gave to the case in his weekly broadcast last night, which I heard with amazement and admiration. I know you had something to do with getting Close to what he did.”[115] St. George, apparently, knew Close personally and had persuaded him to talk about the sedition trial in praise of the defendants, or at least, against the government: “Close, I think, was mighty smart to do it. He is far more smeared than I in Carlson’s last book. I heard Carlson over the air last night on the Columbians. They are now concentrating on Close, Smith, Hart, and the Chicago Tribune.” Dennis is referring to The Plotters, written by John Roy Carlson in 1946. The Plotters, in the words of its author, “is a personal adventure report covering America’s first year of ‘peace’ and is based almost exclusively on undercover activity since V-J Day.” John Roy Carlson was the pen name of Avedis “Arthur” Derounian, an Armenian transplant to America during the First World War. After having attended journalism school at New York University, Derounian chanced upon “an anti-Semitic pamphlet that led him to the American Nationalist party.”[116] From that moment on, he’d spend the better part of his career investigating the members of the far-right.

The beginning of that career came with the publication of Undercover. Joining and reporting on the activities of groups like America First, Derounian characterized his investigation as “[His] Four Years in the Nazi Underworld of America.”[117] In The Plotters, Derounian sought to study the leadership of the organizations he wrote about in Undercover. As he had done for the reporting that formed Undercover, Derounian used his racial ambiguity to blend in with the right-wing extremists he wrote about.[118] From meetings with congressmen sympathetic to the far-right cause to conferences among “the plotters” themselves, Derounian participated in these activities so as to detail extraordinary opposition to the New Deal.[119]

One such conference Derounian wrote about was held in Chicago. Attended by Upton Close and John T. Flynn, both Parsons correspondents, in July of 1945 the conference was sponsored by American Action Inc., a political advocacy organization founded by Merwin K. Hart. Hart was a businessman who had also founded the National Economic Council — both the Council and American Action were vociferously anti-New Deal, anti-Roosevelt, and anti-Communist. Hart, too, had “once charged that Zionists were largely responsible for Hitler's going berserk.”[120] Creating legitimate, public organizations that superficially dealt with “American Action” or “Economics” enabled Hart to covertly advance his conspiratorial agenda. Thus, Hart operated at the level of the conventional and the paranoid. The Chicago conference was to be an expansion of his own methods to a broader group of people.

Hart had brought together Close, Flynn, and a host of other writers, publishers, printers, political operatives, lawyers, and even a former Colonel, to draft, according to Derounian, a “statement of principles” for American Action Inc.[121] Drawing from an American Action booklet, the organization, in its own words, was to be “a militant movement, local and national in scope, carefully planned by Democrats, Republicans, and Independents.” It then outlined its goals, which were as follows: “to organize the great majorities of the Right more effectively than alien-minded radicals have organized the vociferous minorities of the left; to meet head-on the CIO-PAC and its anti-American collaborationists by openly challenging and exposing their terroristic tactics, their smears and their deceits; to purge both major parties of opportunistic leadership that sells out American principles for minorities’ votes; to protect from smear and political reprisal party leaders and public officials who uphold American principles, and drive out those who compromise American principles.” The booklet eerily anticipates the events of the second Red Scare and McCarthyism in its emphasis on purging, organizing against and driving out allegedly “anti-American collaborationists.” And though the organization’s actual influence on politics is uncertain, its successors — groups like the John Birch Society, for example, of which Hart would join and become the New York Chapter leader, and other innocuously named political organizations like the Young Americans for Freedom or the American Legislative Exchange Council — would go on to organize the Right.

Salem Bader, who Derounian describes as an “associate of Close,” organized the Chicago conference. Months later, he’d write a letter to Parsons thanking him for receipt of an issue of a newspaper Parsons had passed along. “I had hoped there would be a letter also telling me about yourself and what you are doing. Permit me to say that you were one of the very few during that convention in Chicago that struck me as most conscientious and public spirited about the whole doings. You certainly understood the international question and most of the boys present did not. They do not realize that at the core of all of what is going on is the international question.”[122]

Gathered in the company of Close and Flynn, Hart and Bader, and several other arch-conservatives, Parsons, too, had attended the conference in Chicago with hopes of rescuing the country from Roosevelt and his legacy. Even among fellow ideologues, however, Parsons stood out for his devotion to the cause of anti-internationalism. It is a cause to which he had dedicated his life, and to which he would now advance among everyday people. A request at the bottom of the portended as much: “Will each of you [the conference attendees] send us the name and address of some veteran of your acquaintance, of World War II, whom you think would be interested in learning something about what is going on in the world today? We will send this man our publication for a number of months.”[123] The promise of education would merely be a means to an end, would be co-opted into advancing political beliefs.

Section 3: Post-War

Parsons was not only an associate of radical conservatives. He knew many people who had nothing to do with politics. Though relationships with these people might have begun apolitically, he nevertheless transformed these benign associations into political ones by trying to influence his friends via mailings, writings, and conversations. Even people who were inclined to agree with him could not keep up with the pace at which he wanted to talk about the politics of the day.[124] In short, Parsons was obsessed with politics until the end of the days, and had been obsessed since the Tyler Kent case, his first significant involvement in politics.

*

In 1948, a few years after the Tyler Kent affair, the sedition trial, the American Action conference and the end of World War II, Parsons suffered a serious bout of appendicitis. He was incapacitated from October to November of 1948 and had a team of nurses care for him while he was recovering.[125] Parsons kept in touch with these young women even after they had left his service, sending them letters, gifts, and beginning a correspondence with their husbands if and when they married. Doris Buck, (“Trained Nurse, Bryn Mawr Hospital”) for example, told Parsons about her role in a local religious youth group.[126] Parsons sent her husband, a junior at West Point, books whose authors criticized Dean Acheson and the Truman administration.[127] The word “criticized,” of course, fails to capture the angry, conspiratorial perspective that surely formed the bases of those books. For example, another pamphlet Parsons sent to Doug Waters, Doris Buck’s future husband, dealt with the case of James Forrestal, a retired Secretary of Defense in the Roosevelt Administration. Forrestal committed suicide in 1949, with many attributing his death to despair over the state of the war. The conspiratorially minded, however, alleged that Forrestal didn’t commit suicide, but was in fact, murdered. The assassins? Members of the Truman administration who sought to punish Forrestal’s refusal to support the creation of the state of Israel. It is a conspiracy theory that is still circulated today (link to amazon book.) Concerning the Forrestal pamphlet and the others sent to him by Parsons, Waters wrote that “fantastic stories of administrative corruption and diplomatic blundering told in the above mentioned articles has my imagination captured. If they are as true to the extent imagined, or even to half of it, things are indeed in a dangerous order. To be frank, I cannot accept them. Part of myself says yes; the other half says no. Perhaps in my indecision lies the tragedy of my generation.” (Need footnote) Parsons and his ilk had planted the seeds of doubt in the mind of a West Point cadet, a cadet who, when weighing the evidence for and against the Roosevelt administration, lamented that he could not immediately see the truth. Such was the effect of Parsons’s paranoid, kitchen-table activism.

Parsons did not only write to former nurses. After serving as a vocal instructor at “Music Meadows: Summer Colony of Music and the Arts at Kennebunkport, Maine,” Parsons kept up a correspondence with former students. Anne Gay Chaffee, a 15-year-old girl in 1949, was among them. He sent her maple sugar candy (“I can’t tell you how happy I was when your maple sugar arrived. A friend of mine was here, and we ate quite a bit of it!!”).[128] If he had the permission of parents of his young correspondents, he took them to football games including the Yale-Harvard game (“I just don’t know where to begin in thank you for such a wonderful day on Saturday!!! Every single thing was just perfect!!”).[129] And of course, he sent news clippings and books — “It was very kind of you to send the books,” wrote Chaffee’s father, “and while I cannot guarantee that she will read all of them now, with all her other reading, I am going to pick out certain important chapters.” Parsons then began to send materials to Mr. Chaffee. “Thank you for the Economic Council letters which I have read very carefully,” wrote Mr. Chaffee. “It is all too true and one can become very depressed in contemplating what we are apparently headed for.”[130] While the contents of the Economic Council letters are unknown, they almost certainly aligned with the views and the tones of Merwin Hart, Parsons, and others like them, especially given the words Mr. Chaffee uses to describe the experience of reading them.