Pacta Sunt Servanda

Volume IV: December 9, 2021

Written by Nicholas Rice

Edited by Judah Millen

Introduction

This essay will investigate the connections between the aesthetic and political philosophies of Alexander Pope, Edmund Burke, and Immanuel Kant, arguing that we can trace in them the development of competing liberal and conservative structures of feeling. In so doing, we follow Eagleton in taking aesthetics not as “a language of art” but as a “social phenomenology”, concerned basically “with all that follows from our sensuous relation to the world” (53). Equipped with this understanding of aesthetics, we can use the concept of ‘structures of feeling’ elaborated in Williams’ The Long Revolution (1961) to describe those ways of thinking about the world that constitute themselves in the cultural hinterland between official discourses and popular understandings and thus connect our aesthetic institutions to our political inclinations.[1]

In characterising these structures as liberal or conservative, we follow Wallerstein’s definition of the terms as they were understood in eighteenth-century Europe. He sees conservatism as defined by an “antipolitical bias” (5); as “reactionary in the simple sense that [it is] a reaction to the coming of what we think of as modernity” (3); as resistant to the imposition of “rational deductive schema on the political process” (3) and the idea that “all [is] possible and legitimate through politics”; as believing in “an organic conception of society” (4) and “the radical inadequacy of the political as a final account of man” (White 1-2); and as grounded in “a penchant for localism” (4). His liberalism, in contrast, “defined itself in opposition to conservatism” (5). It sought to rid “the world of the ‘irrational’ leftovers of the past” in the form of the “false idols of tradition”, believing that “in order for history to follow its natural course it was necessary to engage in conscious, continual, intelligent reformism, in full awareness that the passage of time would naturally bring the greater happiness of the greater number (5-6); otherwise put, it sought “to control the pace of change so that it occurred at what [it] considered to be an optimal speed” (6).

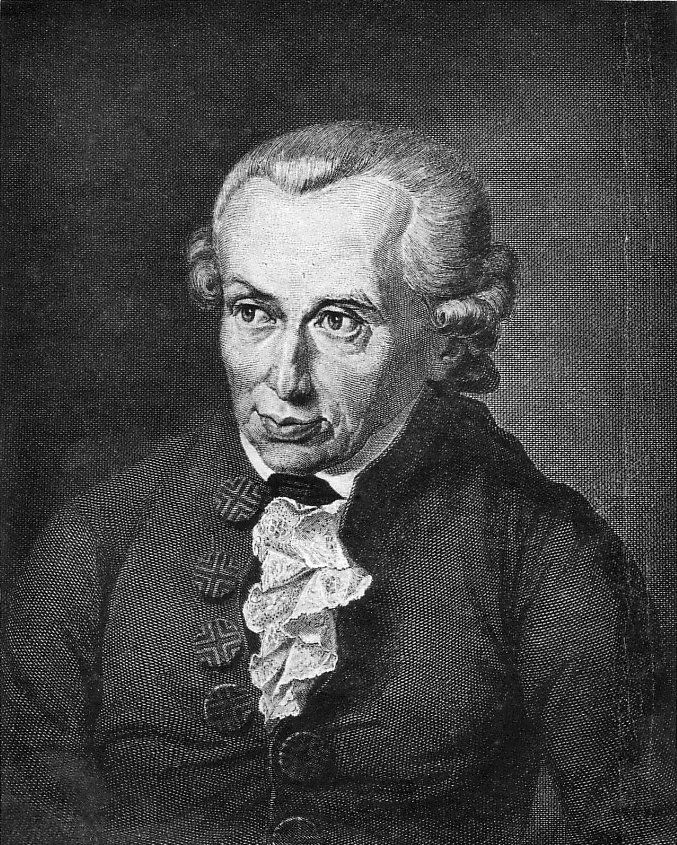

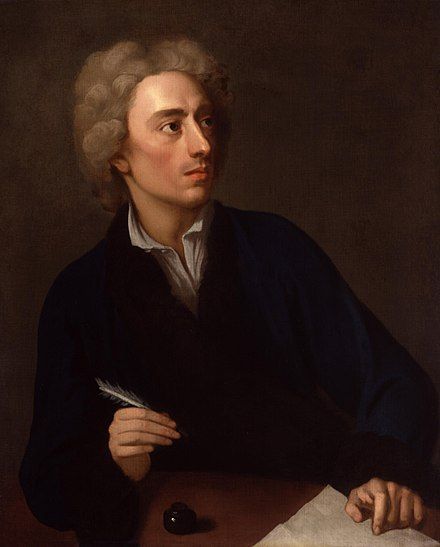

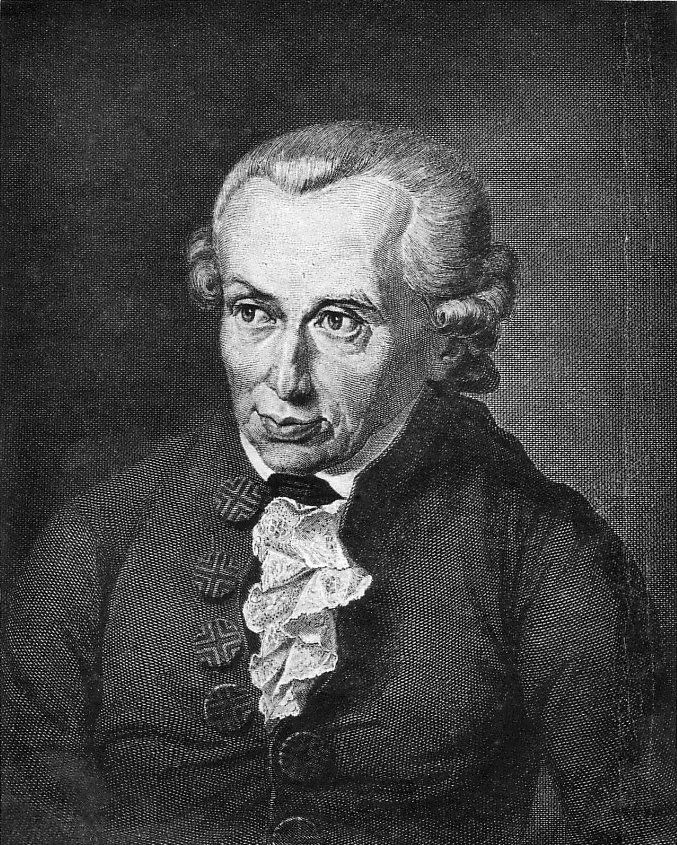

With these understandings of liberalism and conservatism in mind, we will proceed by investigating three important dyads of aesthetic and political philosophy over the course of the eighteenth century: Part I will take up Pope’s Essay on Criticism (1711) (‘Criticism’) and Essay on Man (1734) (‘Man’), Part II will deal with Burke’s A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origins of the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) (‘Inquiry’) and Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) (‘Reflections’), and Part III will consider Kant’s Critique of Judgement (1790) (‘Judgement’) and What Is Enlightenment? (1784) (‘Enlightenment’). For each dyad, we will analyse in turn their aesthetics, their politics, and the structures of feeling they jointly produce. Having examined these three dyads, we will conclude by reflecting on what they tell us about the importance of understanding the confluence of aesthetics and politics in structures of feeling to our ability to critically analyse state power.

Part I: Pope’s Criticism (1711) and Man (1734)

Pope’s Criticism can be easily misread as dogmatically expounding a set of traditional and natural aesthetic criteria as the “Source, and End, and Test of Art” (Criticism line 73). Such readings mistakenly identify endorsements of nature and the canon as Pope’s definitive aesthetic heuristics. Here are two such endorsements (Criticism 67-71, 124-129):

First follow Nature, and your Judgement frame

By her just Standard, which is still the same:

Unerring Nature, still divinely bright,

One clear, unchang’d, and Universal Light,

Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart,

At once the Source, and End, and Test of Art.

…

Be Homer’s Works your Study, and Delight,

Read them by Day, and meditate by Night,

Thence form your Judgement, thence your Maxims bring,

And trace the Muses upward to their Spring;

Still with Itself compar’d, his Text peruse;

And let your Comment be the Mantuan Muse.

Both of these passages undoubtedly laud the importance of nature and the canon as aesthetic standards. The enumeration of “Nature” as the first aesthetic commandment is reinforced by its characterisation as unitary and ubiquitous, its “Universal Light” constituting the source of all “Life, Force, and Beauty”. The same is true of “Homer” – here synecdochal for the canon of antiquity – whose “Text” is taken as the “Spring” of all “Maxims” of aesthetic “Judgement”. Importantly, however, Pope proposes these traditionalist heuristics not to establish them as dogma but to “confront” what Alvarez describes as “the threat of anarchic individualism posed by the relativity of taste and the proliferation of print” (104). Following Alvarez, these heuristics are thus not “abstract universals that demand submission from poets and critics” but things that “can be transgressed and augmented through successful poetic practice,” meaning that Pope is essentially arguing for “a dynamic form of aesthetic universality” (111).

This is apparent on the level of form: in choosing to write a poem instead of an essay – as Addison did in his aesthetic essays in the Spectator (1711-1712) – he appeals both to the logic of poetic argument and to the alogical meanings that arise from the aesthetic perception of thematic and phonological poetic patterns. The argument of his text is therefore not strictly expository but playfully expansive: for instance, the hylomorphic nature of beauty as constituted from parts and wholes is explored with the use of concatenated sentence fragments (Criticism 243-246), the righteousness of the Aristotelian preference for moderation is expressed in the balancing of metrical feet (Criticism 740-744), and the use of rhyme in heroic couplets is used to obliquely deride and laud different poetic subjects (Criticism 26-29). Further, the language of improvement in which art is described gestures towards the possibility of developing new aesthetic standards: though attention must be paid to nature and tradition, this language indicates that these aesthetic standards can still be altered diachronically. This is clearest when Pope deploys a discourse of subject-object relation to describe the way art – and the aesthetic standards it enlists – can act on its objects (Criticism 297-300, 315-317):

True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest,

What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest,

Something, whose Truth convinc’d at Sight we find,

That gives us back the Image of our mind …

…

But true Expression, like th’unchanging Sun,

Clears, and improves whate’er it shines upon,

It gilds all Objects, but it alters none.

The function of “true expression” here is to dress “to advantage” its “Objects”. Given that it cannot “alter” them essentially, its sole aim is their aesthetic improvement by arrangement into forms of beauty or sublimity. There is thus room in his aesthetics for meliorist improvement based on a foundational respect for nature and the canon.

Just as we may easily misread Pope’s Criticism as advancing a dogmatically traditionalist and naturalist aesthetics, so too may we easily misread the politics of his Man as advancing an aristocratic faith in traditional hierarchy. In it, Pope venerates “that Chain which links th’immense design” (Man 4.333) and echoes the Miltonian injunction to “be lowly wise” (Man 8.173) by accepting limits on our knowing imposed by our human status (Man 4.394-8):

Whatever is, is right;

That reason, passion, answer one great aim;

That true self-love and social are the same;

That Virtue only makes our Bliss below;

And all our Knowledge is, ourselves to know,

These concluding lines of the final canto certainly echo an injunction to epistemic and ontic humility in their emphasis on the righteousness of present circumstances and situation of our epistemic telos in our own nature. The outline of a conservative structure of feeling thus begins to form. However, this declaration does not enjoin a conservative quietude that seeks simply to maintain the blunt contingency of given circumstances; rather, as was the case of his emphasis on nature and the canon in aesthetics, it seeks to give bounds to the proper realm of political change. This notion of giving bounds to the realm of political action is made apparent morphologically through metaphors of vision and phonologically through repeated deployments of balanced syntaxes and metrical patterns. Though human vision is partial and occluded, there exists a “God of all,” who sees “a hero perish or a sparrow fall” with “equal eye,” since a “bubble” and a “world” are of equal insignificance before him (Man 1.87-90). In view of this humbling epistemic myopia before a divine omnipotence, we are enjoined to caution in urging political change. The importance of this via media of cautious change is further emphasised by Pope’s metrical balance and coupled rhyme (Man 1.289-294):

All Nature is but Art, unknown to thee;

All Chance, Direction, which thou canst not see;

All Discord, Harmony, not understood;

All partial Evil, universal Good:

And, spite of Pride, in erring Reason’s spite,

One truth is clear, ‘Whatever is, is right.’

The phonological sense of balance and order generated by the stable coupled rhyme scheme and regular metrical patterns underwrites the thematic principles of “art”, “direction”, “harmony”, “good”, and “reason” that the lines discuss, together creating an aesthetic impression of the political importance of preserving order. Political progress may still be made towards discovering the art we cannot find, the direction we cannot understand, the harmony we cannot define, and the good we cannot see; in so doing, however, we must remain cognisant of the aesthetic humility enjoined by the epistemic and ontic constraints on our experience.

With this understanding of Pope’s aesthetics and politics in mind, we can see the emergence of liberal structures of feeling in his work. Pope’s belief in certain aesthetic certainties – i.e., the need to depend on nature and the canon in creating and judging art – and political necessities – i.e., the need for cautious change given the epistemic and ontic boundaries that encircle us as humans – appears conservative. This conservative portrait, however, is complicated by the qualifications to it elaborated above: reasonable aesthetic innovation can occur, just as political order can be modified within reasonable bounds. With this meliorist possibility in mind, Pope’s aesthetics and politics can best be characterised not in Alvarez’s terms as “totalising or totalitarian” (111) or possessing “democratic potential” (116) but as enacting an embryonic form of Wallerstein’s liberalism in its preference for gradual and rational change.

Part II: Burke’s Inquiry (1757) and Reflections (1790)

The understanding of aesthetics advanced by Burke in his Inquiry is significantly more schematic than that advanced by Pope. Taking “taste” to be “that faculty … [by] which we are affected with, or which form a judgement of the works of imagination and the elegant arts” (Inquiry 13), Burke affirms a singular understanding of taste as a guide to proper conceptions of the sublime and beautiful (Inquiry 22-23):

Whilst we consider taste merely according to its nature and species, we shall find its principles entirely uniform; but the degree in which these principles prevail, in the several individuals of mankind, is altogether as different as the principles themselves are similar.

This “taste” that is the “true standard of the arts” is simultaneously “uniform” and “in every man’s power”, (Inquiry 49) meaning that where there exists dissent from Burke’s unitary understanding, it is deemed the product of a “defect of judgement” (Inquiry 23). Importantly, the faith this shows Burke placing in the righteousness of universalising his aesthetic intuitions is indicative of a faith in intuition understood by Wallerstein as characteristic of conservatism.[2] Within this unitary theory of taste, beauty – defined by Burke strictly as “that quality or those qualities in bodies by which they cause love, or some passion similar to it” (Inquiry 83) – is understood schematically as a concept denoting properties of smallness, smoothness, variety, non-angularity, delicacy, clear and bright coloration, and diversity (Inquiry 107). By reducing the beautiful to a set of characteristics (Inquiry 107) acting “mechanically upon the human mind” by the intervention of the senses (Inquiry 102), Burke radically stabilises understandings of beauty in a manner unlike Pope. A similar fixity is applied to the sublime. For Burke, the sublime arouses feelings of “horror,” “astonishment,” “admiration, reverence, and respect”; (Inquiry 53) its “ruling principle” is “terror”, (Inquiry 54) which describes the feeling of “delight” (Inquiry 47) that comes with having escaped pain. As with beauty, a set of properties characterise the objects Burke believes we may call sublime: power (Inquiry 59), vastness (Inquiry 66), infinitude (Inquiry 67), greatness in dimension (Inquiry 69), difficulty (Inquiry 71), magnificence (Inquiry 71), loudness (Inquiry 75), suddenness (Inquiry 76), and atavism (Inquiry 77).[3]

Given his discussions of the “society of the sexes” that exists between men and women and the “general society” that exists among men, women, animals, and “the inanimate world”, (Inquiry 37) in addition to his identification of passions of “self-preservation” and “society”, (Inquiry 35) Burke is evidently concerned with the politics of this aesthetics of the sublime and the beautiful. According to White, for Burke, “to speak of what we think of as the distinct sphere of aesthetics was also necessarily to speak of power, gender, moral sentiment, tradition, and social hierarchy” (508). This connection between aesthetics and political behaviour is mechanised by behaviourist theories of sympathy, imitation, and ambition. Beauty, for instance, is motivated by sympathy and imitation. Its “social quality” – that is, its ability to “inspire us with sentiments of tenderness and affection towards [other] persons” (Inquiry 39) – arises from the sympathy in which we engage by “enter[ing] into the concerns of others” (Inquiry 41) through “poetry, painting, and other affecting arts” (Inquiry 41). We only arrive at this shared ability to enact proper taste and detect the beautiful in objects via imitation, whereby our “natural constitution” moves us to “have a pleasure in imitating” and “copy whatever [others] do” (Inquiry 45). The politics of Burke’s aesthetics is thus partly founded on a social love produced by common understandings of beauty and mechanised by sympathy and imitation.

If the beautiful defines our sociality, the sublime defines our relationship to the state. Ryan notes Burke’s sublime denigrates the perceiving subjectivity (266): its basic affect is a “delight” (Inquiry 45) at having been spared by a greater power, not a sense of transcendence into the rational fullness of our being as in Kant. The terror we feel in the sublime – of having escaped a great danger before an entity beyond our ontic or epistemic access – is the kind of reverence Burke wishes the citizen to abide before the state in his Reflections (80):

[The state] is to be looked on with other reverence because it is not a partnership in things subservient only to the gross animal existence of a temporary and perishable nature. It is a partnership in all science; a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue and in all perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born. Each contract of each particular state is but a clause in the great primeval contract of eternal society, linking the lower with the higher natures, connecting the visible and invisible world, according to a fixed compact sanctioned by the inviolable oath which holds all physical and all moral natures, each in their appointed place.

The language of totality, sense of temporal infinitude, suggestion of epistemic inaccessibility, and discourse of sanctity that describe the state in this passage recapitulate the properties of the sublime identified by Burke above. He is at times even more explicit in characterising this subject-state relation as one of sublimity, for instance arguing that “sublime principles ought to be infused into persons of exalted situations, and religious establishments provided that may continually revive and enforce them” (Reflections 77).[4] Given this association of sublimity with political submission, it appears surprising that Burke associates it behaviourally with the disruptive force of ambition. To prevent an “eternal circle” of aesthetic recycling created by sympathy and imitation, Burke suggests that, “God has planted in man a sense of ambition, and a satisfaction arising from the contemplation of his excelling his fellows in something deemed valuable amongst them” (Inquiry 46). However, as Eagleton explains, by displacing this ambitious impulse from the political to the aesthetic domain, the state successfully guarantees the awe of its subjects while ensuring that their ambition is channelled towards neutered versions of those “traditionalist patrician virtues of daring, reverence, free-booting ambition [that] must be at once cancelled and preserved” in the modern state (57). In sum, therefore, the politics of Burke’s aesthetics moves us to associate society with beauty and the state with sublimity, approaching the former with love and the latter with awe.

Where Pope offered us a liberal structure of feeling in which stable aesthetic and political understandings were trusted but subject to change, Burke offers us fixed aesthetic concepts of the beautiful and the sublime with fixed political connotations: the beautiful generates love among subjects while the sublime engenders the obedience of those subjects to the state. In his preference for intuition over reason in the Inquiry and political reactionism in the Reflections, Burke advances a clearly conservative structure of feeling.

Part III: Kant’s Judgement (1790) and Enlightenment (1784)

Where Pope was largely unconcerned with aesthetic categories and Burke dealt in a dichotomy of the beautiful and the sublime, Kant establishes a fourfold aesthetic scheme comprising the sublime, the agreeable, the beautiful, and the good. As Ryan explains, Kant’s sublime is importantly distinct from Burke’s in that where Burke’s sublimity involves a “critique of reason” and suggests “the subject’s sese of limitation,” Kant’s sublimity “allows us to intuit our rational capacity” and overcome our initial sense of limitation before the sublime (266). Otherwise put, Kant’s sublime, after confronting us with “a momentary inhibition of the vital forces”, is “followed immediately by an outpouring of them that is all the stronger” (Judgement 98). Turning from the sublime, Kant offers us the following definition of his three remaining categories: “we call agreeable what gratifies us, beautiful what we just like, [and] good what we esteem … [or] endorse, … i.e., that to which we attribute ... an objective value” (Judgement 52). The category of the agreeable describes what we identify as pleasurable, which is the product of “sense impressions that determine inclination,” “principles of reason that determine the will” and “forms of intuition that we reflect on and that determine the power of judgement” (Judgement 47). The beautiful, by contrast, is perceived by a “taste” for the object not “based on a concept (since then it would be the good)” (Judgement 57) but on a “favour [that] is the only free liking”; free “in the sense that we are not compelled to identify something as beautiful by any “interest … of sense or reason” (Judgement 52). It is distinguished from the good only in the sense that the good relies on “a [determinate] concept of … what sort of thing the object is [meant] to be” (Judgement 49) and is thus determined “by the presentation of the subject’s connection with the existence of the object” (Judgement 51).[5]

Though Kant understands the beautiful and the good as universal in a manner analogous to Pope and Burke, we cannot understand the particularity of his understanding without addressing the fundamental difference between the implicit Cartesian dualism of Pope and Burke and Kant’s transcendental idealism. Suggesting a bifurcated reality of noumena (i.e., things in themselves) and phenomena (i.e., things as they appear), Kant argues that we are unable to cognize noumeous realty, meaning we are restricted to the sensible and rational perception of things as they appear to us phenomenally.[6] Therefore, an object cannot be sublime or beautiful for Kant in the same way it can for Burke; the sublime object, for instance, cannot itself be sublime but can only “exhibit a sublimity that can be found in the mind” (Judgement 99). Following onto-epistemology, the beautiful is defined by Kant not as a conceptual category instantiated by objects possessing common characteristics – as was the case for Pope and Burke – but as a descriptor that denotes objects that cause pleasure in perceiving subjects.[7] He is able to assume this uniform response of pleasure by positing what Zimmerman calls the “Kantian mind”; that is, the taking of the mind to be “a delicately balanced machine which is individuated in this or that body [but] whose machinations are repeatable and duplicative even though they occur in different bodies” (337). On the basis of this assumption, Kant claims subjective “universal validity” (Judgement 57) for his understanding of the beautiful and objective “universal validity” (Judgement 58) for his notion of the good. There is a basic ambiguity concerning whether these claims of objective and subjective universality are “constitutive” and “factual” or “regulative” and “imperatival”, to use Rogerson’s (passim) terminology. Where constitutive ideas describe things as-they-are, regulative ideas provide recommended heuristics for achieving things as-they-should-be (Rogerson 305); where factual ideas describe what we could rationally expect of all people, imperatival ideas describe what we could rationally demand of all people (Rogerson 304). It is important to understanding the politics of Kant’s aesthetics that we take his understandings of beauty and the good as simultaneously factual-constitutive and imperatival-regulatory.

The politics of Kant’s aesthetics is resumed in his Enlightenment with respect to both the problem of universal validity and the politics of the sublime. In the case of the good, the coincidence of factual-constitutive and imperatival-regulatory ideas is made apparent in his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) (‘Groundwork’), wherein the concept of the “kingdom of ends” (Kant 83) denotes that political community in which the moral imperative towards the good – i.e., Kant’s categorical imperative – is universally abided. This imperative is abided not because it is enforced in the first instance in the manner of an imperatival-regulatory idea but because it is self-given (Groundwork 66) – i.e., factual-constitutive – and thus assumes in the second instance the status of an imperatival-regulatory idea. This same logic applies to the beautiful in Kant’s Enlightenment, wherein Kant declares that having “the courage to use your own intelligence is … the motto of the enlightenment” and that “enlightenment among men” can only be achieved by “the public use of a man’s reason [being] … free at all times” (1). The only way, Kant argues, to move from an “age of enlightenment” to “an enlightened age” is to grant to all the freedom to “work freely” and “use their minds securely” (Enlightenment 2). Only through the free use of reason demanded by Kant can we come to freely deploy our aesthetic powers and thus come to realise constitutively and factually the imperatival and regulatory universal validity of our understandings of beauty and the good. This same political conclusion is gestured towards by Kant’s aesthetics of the sublime. By confronting us with our limitations and then allowing us to rationally transcend them, a relationship of sublimity to the state allows for the self-actualisation and liberation of the political subject as a free and rational agent.

In view of this analysis of Kant’s aesthetics and politics, there are three important conclusions we can make about the structure of feeling operative in his work. The first concerns the sublime. In conceiving of a sublime defined by our rational overcoming of ontic and epistemic limitations, Kant contradicts the Burkean injunction to awed submission before a sublime state and excels Pope’s belief in the possibility of progress grounded in an appreciation for tradition and natural law.[8] The aesthetic definition of the Kantian subject’s relationship to the state as sublime thus affirms a political belief in the free rational subject advanced by Wallerstein’s liberalism. Our second conclusion concerns the agreeable, which accounts for the interested pleasure individuals take in phenomenal objects through sense and reason. As a private category not concerned with shared aesthetic preferences, it enacts the belief propagated by Enlightenment liberalism that there exist distinct private and private spheres with distinct codes of behaviour. Our final conclusion concerns the importance of ideas of objective and subjective universal validity, in that these claims to universality illustrate a liberalist understanding of political subjects as self-legislating, erecting imperatival-regulatory ideational structures on the basis of constitutive-factual ideas understood to inhere in the rational expression of human nature. As a canonical essay in the history of Enlightenment thought, Kant’s Enlightenment illustrates a faith in the possibility of a more enlightened political community emerging from the free exercise of aesthetic reason. The structure of feeling motivated by Kant thus vitiates Burke’s conservatism and accelerates Pope’s nascent liberalist tendencies, promising an enlightened political future made free and rational by the universal validity of our aesthetics.

Conclusion

The connections between aesthetics and politics we have identified in Pope’s embryonic liberalism, Burke’s conservatism, and Kant’s fully-elaborated Enlightenment liberalism allow us to trace the historicity of two major structures of feeling that connect the way we experience the world aesthetically to the way we act in it politically.

Our ability to do this is important. In elaborating these aesthetic-political connections, we see the truth of Eagleton’s statement that “the whole concept of the aesthetic [is] indissociable from an emergent project of bourgeois political hegemony” that sought to “redefin[e] the relations between law and freedom, [the] mind and the senses, [and the] individual and the whole” (54).[9] Given the involvement of the aesthetic in this political project, it is thus impossible to posit aesthetic conclusions without political consequences since they necessarily participate in structures of feeling with political ramifications. Only the aesthetic is capable of producing what Eagleton calls a “spontaneous consensus among social subjects, … whose locus is neither the state (ultimately a coercive force) nor civil society (a place of atomised, competitive individuals) but the realm of ‘culture’ itself” (55). In his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935), Benjamin was aware of this aesthetic power over culture. He argued that fascism was not a political but an aesthetic movement that “attempt[ed] to organise the newly created proletarian masses without affecting the property structure”, instead offering them “a chance to express themselves” (Benjamin 241). It was engaged, therefore, in the aestheticization of politics, just as “communism” was conversely engaged in “politicizing art” (Benjamin 242). By tracing, as we have done in this essay, the liberal and conservative structures of feeling motivated by Pope, Burke, and Kant we can become more adept at identifying and combating the fascist structures of feeling emergent again in our time.

Bibliography

Books

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. 1935. Edited by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn, New York, Schocken Books, 1969.

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Burke, Edmund. Reflections on the Revolution in France. E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1950.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgement. Translated by Werner S. Pluhar, Hackett Publishing Company, 1987.

Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. 1785. Translated by Mary Gregor. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Milton, John Paradise Lost. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Pope, Alexander. The Poems of Alexander Pope. Edited by John Butt, Yale University Press, 1963.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789-1914, University of California Press, 2011.

White, Reginal James. British Political Tradition Book 4: The Conservative Tradition, edited by Reginald James White, Nicholas Kaye Press, 1950.

Chapter in Edited Book

Marvin Perry, et. al. Sources of the Western Tradition, Volume II, 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995, pp. 56-57.

Articles

Alvarez, David. “Alexander Pope’s ‘An Essay on Criticism’ and a Poetics for 1688.” Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, 1660-1700, vol. 39, no. 1/2, 2015, pp. 101–123.

Eagleton, Terry. “Aesthetics and Politics in Edmund Burke.” History Workshop, no. 28, 1989, pp. 53–62.

Rogerson, Kenneth F. “The Meaning of Universal Validity in Kant’s Aesthetics.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 40, no. 3, 1982, pp. 301–308.

Ryan, Vanessa L. “The Physiological Sublime: Burke's Critique of Reason.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 62, no. 2, 2001, pp. 265–279.

White, Stephen K. “Burke on Politics, Aesthetics, and the Dangers of Modernity.” Political Theory, vol. 21, no. 3, 1993, pp. 507–527.

Zimmerman, Robert L. “Kant: The Aesthetic Judgment.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 21, no. 3, 1963, pp. 333–344.

Websites

n.a., “Structures of feeling.” Oxford Reference. Date of access 11 May 2021, <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100538488>

Endnotes

[1] We rely here on the understanding of structures of feeling provided by the Oxford Reference (n.p.):

[Raymond] Williams would develop this concept further, using it to problematize (though not refute) Antonio Gramsci’s concept of hegemony. Hegemony, which can be thought of as either ‘common sense’ or the dominant way of thinking in a particular time and place, can never be total, Williams argued, there must always be an inner dynamic by means of which new formations of thought emerge. Structure of feeling refers to the different ways of thinking vying to emerge at any one time in history. It appears in the gap between the official discourse of policy and regulations, the popular response to official discourse and its appropriation in literary and other cultural texts. Williams uses the term feeling rather than thought to signal that what is at stake may not yet be articulated in a fully worked-out form but has rather to be inferred by reading between the lines. If the term is vague, it is because it is used to name something that can really only be regarded as a trajectory. It is this later formulation that is most widely known.

[2] See Burke (Inquiry 31):

Nothing is more certain to my own feelings than this. There is nothing which I can distinguish in my mind with more clearness than the three states of indifference, of pleasure, and of pain.

[3] For a full demonstration of the schematicity of Burke’s understanding of the beautiful and the sublime, see the conclusion to Part III of the Inquiry (113-4):

For sublime objects are vast in their dimensions, beautiful ones are comparatively small; beauty should be smooth, and polished; the great, rugged, and negligent; beauty should shun the right line yet deviate from it insensibly; the great in many cases loves the right line, and when it deviates, it often makes a strong deviation; beauty should not be obscure; the great ought to be dark and gloomy; beauty should be light and delicate; the great ought to be solid and even massive. They are indeed ideas of a very different nature, one being founded on pain, the other on pleasure; and however, they may vary afterwards from the direct nature of their causes, yet these causes keep up an eternal distinction between them, a distinction never to be forgotten by any whose business it is to affect the passions.

[4] The fact that Burke’s own relationship to state power is characterised by feelings of sublimity is everywhere apparent in the Reflections. See, for instance, his description of the humiliation of Marie Antoinette (Burke Reflections 63):

It is now sixteen or seventeen years since I saw the queen of France, then the dauphiness, at Versailles, and surely never lighted on this orb, which she hardly seemed to touch, a more delightful vision. I saw her just above the horizon, decorating and cheering the elevated sphere she just began to move in—glittering like the morning star, full of life and splendour and joy. Oh! what a revolution! and what a heart must I have to contemplate without emotion that elevation and that fall! Little did I dream when she added titles of veneration to those of enthusiastic, distant, respectful love, that she should ever be obliged to carry the sharp antidote against disgrace concealed in that bosom; little did I dream that I should have lived to see such disasters fallen upon her in a nation of gallant men, in a nation of men of honour and of cavaliers. I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. But the age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists; and calculators has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever. Never, never more shall we behold that generous loyalty to rank and sex, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom. The unbought grace of life, the cheap defence of nations, the nurse of manly sentiment and heroic enterprise, is gone! It is gone, that sensibility of principle, that chastity of honour which felt a stain like a wound, which inspired courage whilst it mitigated ferocity, which ennobled whatever it touched, and under which vice itself lost half its evil by losing all its grossness.

[5] Kant elaborates this scheme with reference to the example of a rose (Judgement 59):

The rose is agreeable (in its smell), is also aesthetic and singular, but it is a judgment of sense, not of taste. For a judgment of taste carries with it an aesthetic quantity of universality, i.e., of validity for everyone, which a judgment about the agreeable does not have. Only judgments about the good, though they too determine our liking for an object, have logical rather than merely aesthetic universality; for they hold for the object, as cognitions of it, and hence for everyone.

[6] As Zimmerman puts it (333):

[For Kant,] in aesthetic experience we are not concerned with an object but with the representation of an object in the subject's mind. It is the object as a perceived entity that produces the feeling of beauty.

[7] Rogerson explains how for Kant, “to claim that an object is beautiful is to say that appreciating the object is an intrinsically pleasurable experience, a pleasure not peculiar to me, but in some sense one that can be imputed rightfully to all” (301).

[8] Here, I take issue with White, who ignores the important political consequences of Kant’s aesthetic of the sublime (508):

I will suggest that Burke's notion of the sublime should not be considered simply as a stepping-stone toward Kant but as superior to Kant in terms of its relation to moral-political reflection. Kant's sublime ultimately reduces to an experience whose main value lies in its getting us to marvel at how elevated the human moral will is above the world of social and natural phenomena.' It gives us a taste of our participation in the infinite, in the noumenal world. In conceiving of the sublime in this way, Kant unwittingly involves himself in a "humanizing" of the sublime, precisely what Burke finds to be at the heart of what disturbs him about the mix of will and politics in modernity.

[9] Eagleton goes on (54):

The aesthetic was the way power, or the Law, would be carried into the minutest crevices of lived experience, inscribing the very gestures and affections of the body with its decrees. … In a world that was rapidly shifting away from autocratic regulation and towards the free autonomy of the subject, the aesthetic was the way in which existing regimes of power could control and regulate the behaviour of subjects. The conditioning of the aesthetic sensibilities of political subjects became "a new kind of political requirement, in a world where the dismantling of the centralised structures of absolutism, and the emergence of marketplace relations, meant that the human individual had to become his or her own seat of self-government.