Interview and transcription by Zoe Bernicchia-Freeman

August 14, 2021

Dr. Shaun Wallace is a social historian of the eighteenth and nineteenth century United States. His research examines transatlantic slavery, with a particular focus on fugitives and fugitivity in the Antebellum South. He was awarded his PhD from the University of Stirling, UK, and is currently a Lecturer in United States History at the University of Bristol, UK. His forthcoming monograph In Pursuit of Freedom: Enslaved Runaways and Resistance in the U.S. South, 1790-1860 stands to make a major contribution to historiographical understandings of slavery throughout the Atlantic world from the turn of the nineteenth century as only the second major quantitative study of fugitivity in the United States. His Fugitive Slave Database, a unique digital archive preserving American fugitivity advertisements from the American South, is the first systematic investigation of fugitivity in early national Georgia and Maryland.

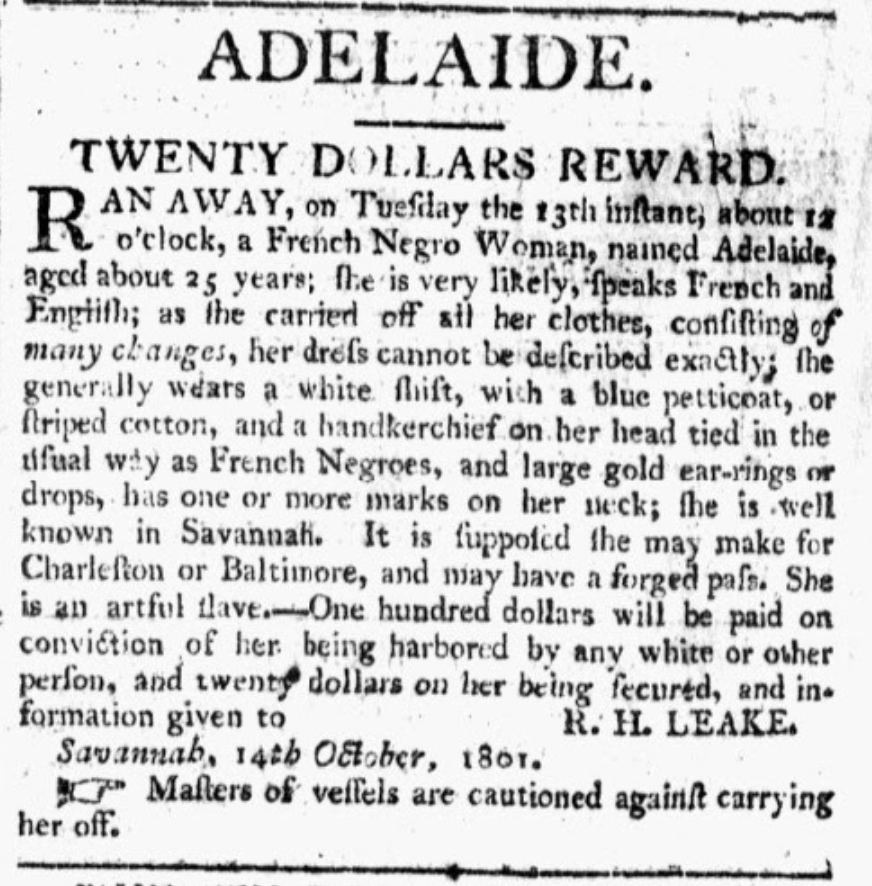

Zoe Bernicchia-Freeman (ZBF): To begin, can you provide me with some background information about fugitive slave advertisements? How would you explain the purpose of these notices to an individual who was not familiar with the history of Antebellum slavery and print culture?

Shaun Wallace (SW): The first American fugitive slave advertisement was published in The Boston News-Letter in 1705 by a Scotsman named John Campbell, who served as the postmaster of Boston. Its publication marked the birth of an advertising genre that existed until approximately 1864, near the end of the American Civil War. We don’t really know how many advertisements were published in total over slavery’s lifetime, but a conservative estimate rests at around 100,000.

Regarding the purposes and intentions behind these advertisements, I could give you many different answers. In its most basic definition, this type of notice was taken out to publicly identify enslaved fugitives for the goal of recapturement. When an enslaved person escaped, advertisers with vested interests (e.g., slaveholders, jailers) constructed notices and sent them to their local printers to be published in newspapers or circulated. The majority of these advertisements included physical descriptions of the fugitive and a monetary reward for recapturement. Other details sometimes included the date of the escape, likely destinations, and any other identifying characteristics.

At first glance, one might look at these sources and think that they all look the same; many notices included similar details, and it’s easy to group them together by their common typographical attributes. However, as historians we must remember that every advertisement is unique.1 Every single fugitive was a unique person with specific attributes, skills, and motivations to escape. Different slaveholders also undoubtedly had different motivations for taking out certain advertisements and for manufacturing them the way they did. Some notices, for instance, contained incredibly vague descriptions, which raises the question: were all of these advertisements actually being used to identify fugitives, or were some of these notices simply published as an attempt to exert power and control? Perhaps a way for slaveholders to have the last word after fugitives escaped? Overall, these sources provide us with historical insight into the lives of countless fugitives whose experiences were never otherwise recorded. This is where my work comes in.

ZBF: At the heart of your inquiry is the Fugitive Slave Database, which you worked on at the University of Stirling as part of your doctoral research project. Can you tell me more about how you compiled this fascinating archive?

SW: When I began my PhD, my idea from day one was quite broad. I wanted to know who the fugitives of Georgia and Maryland were, specifically from 1790 to 1810. Other databases allowed historians to access scans and transcripts of fugitive advertisements from various eras and locations, but no piece of work had ever attempted to build detailed prosopographies of recorded fugitives from Georgia and Maryland during those years.

I began going through every single page of every newspaper published in Georgia and Maryland between 1790 and 1810. Whenever I found a fugitive slave advertisement, I recorded its contents in a database, which was constructed and populated to include as many details as possible. ID numbers were assigned to each notice and fugitive. These ID numbers were then linked to descriptions of identifying characteristics (e.g., names, ages, appearances), as well as any geographical comments (e.g., escape locations, likely destinations) and fugitive attributes (e.g., skills, personality traits). That way, if we wanted to look into any of these individuals or make statistical comparisons between different profiles, all of the necessary details were easily accessible. But, as a historian, the last thing I wanted to do was reduce human beings to numbers. So, we included both quantitative and qualitative details in order to build as many well-rounded profiles as possible. For example: if a fugitive was described as “musically talented,” these types of details made it into the database as well.

Over the course of three years, we developed a database which recorded and categorized as many details as possible from every fugitive slave advertisement we found. The database currently holds more than 12,500 unique records. I worked with my supervisor, Dr. Colin Nicolson, who supported me; without him, this project would not have been possible.

ZBF: Since these sources were authored by slaveholders, how can we reconcile their inherent bias? Can the details in these advertisements be taken as fact?

SW: That is a very important question. For a long time, historians felt uneasy about using these sources – and for good reason. I want to make clear that none of these notices should be conclusively accepted as objective fact; since they were authored by slave-owning men and women, their inherent biases urge us to investigate the socio-political intentions behind every source. When describing a fugitive’s physical attributes, for instance, a slaveholder is unlikely to publicly accept blame for any visible injuries or scars. A few haunting instances come to mind where fugitives’ injuries were explained away in suspicious descriptions that seemed to conceal brutal physical abuse.

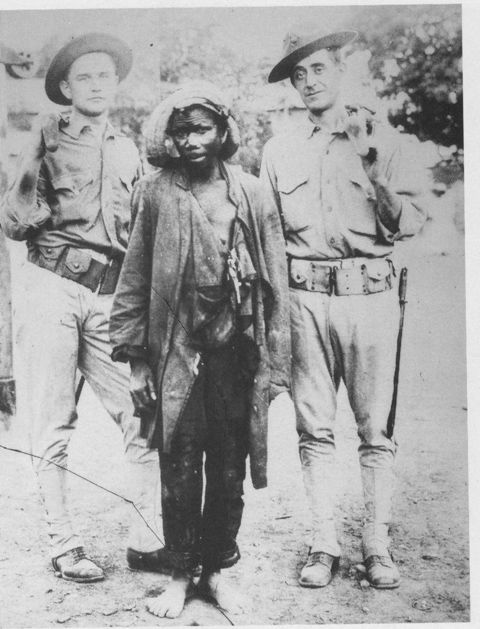

Clearly, these sources must be handled with caution as they were created to assert and maintain Antebellum white supremacy and power. However, so long as we remain mindful and critical of the authors’ interests, these sources have the potential to help us uncover historical trends about enslaved individuals whose stories have never been investigated.

As a historian constructing a database of primary source material, it was not my job to go into these sources and start meddling with their content. This is why I did not analyze any of the sources while the database was being populated; my sole concern was to capture everything. By providing digital profiles of all available source content, this database allows future historians to engage critically with the advertisements themselves and conduct their own investigations. Most importantly, we are not using these sources the way slaveholders intended; rather than using them to dehumanise enslaved individuals and reinforce historical systems of white supremacy, we are using them to revive the stories of fugitives who did not necessarily document their experiences of enslavement. Ignoring these sources would fail to do justice to the countless fugitives who risked their lives in the pursuit of freedom.

ZBF: After you finished populating the database, which stories and variables piqued your interest the most?

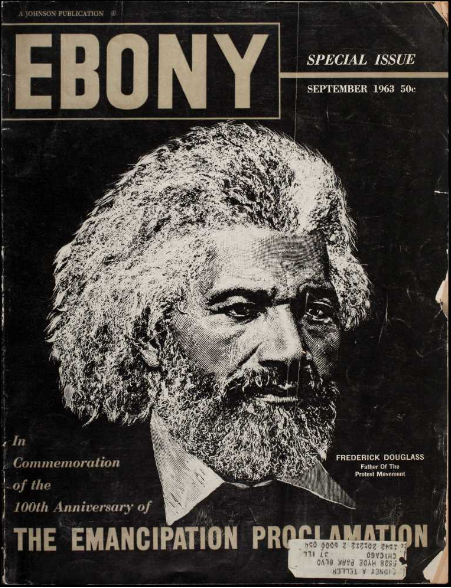

SW: The authors of these sources used their words very deliberately. Something for me that became fascinating was the use of the word “artful” to describe fugitives. When I was inputting data, this adjective kept coming up, and many of the advertisements which referred to “artful” fugitives also included other common traits. For example: “artful” fugitives were often described as “cunning” individuals who would attempt to “deceive” people by changing their names, changing their appearances, endeavoring to pass as free people, and so on. Overall, the word “artful” was usually employed to describe an unpredictable individual who challenged the status quo and was not easily controlled. This is why exploring “artfulness” is very similar to exploring literacy. In Frederick Douglass’ narrative, his master fears him becoming literate because he equates literacy with rebelliousness. However, since the instruction of enslaved people in reading and writing was illegal in places like Georgia (but not Maryland), slaveholders were not likely to admit fugitive literacy in public advertisements. This means that adjectives like “artful” may have been used as coded language between slaveholders to refer to fugitives who were literate… and these types of links bring up even more questions. Using fugitive slave advertisements to establish literacy rates is, in itself, something quite new, but it’s one of the variables I’m particularly drawn towards because most of my initial interest in fugitivity came from reading Douglass’ narrative.

ZBF: I was fortunate enough to read a draft of the first chapter of your forthcoming monograph, In Pursuit of Freedom, and was particularly drawn to your discussion of fugitive slave advertisements as a “historical snapshot … into black agency, empowerment, and self-actualization.” Can you elaborate on how you engage with the topic of fugitivity in your work, and why you were initially drawn to it?

SW: When I began studying the literature of Antebellum fugitivity, I noticed that academics repeatedly used the phrase “running away.” I found this odd because “running away” contains many assumptions. First off, fugitives didn’t necessarily “run” away; they escaped on horses, on boats, in canoes, for short-term purposes, for long-term purposes … many unique variables contributed to each fugitive’s situation. Second, while fugitivity was often reactive (e.g., many fugitives escaped in response to abusive treatment, inhumane labour conditions, or out of fear of punishment), the term “running away” only captures the push factors of fugitivity. But, as S. Charles Bolton articulates in his new work, there must have been a pull factor as well.

Fugitivity was, I argue, a fundamentally political act. Every individual who escaped knew that they were likely to be punished for such behaviour. With the expansion of American print culture and the rise of American newspapers from the end of the eighteenth century, slaveholders were emboldened by their increasing ability to hunt down fugitives through the written word. But enslaved men and women never stopped trying to escape, which was truly remarkable. “Running away” was not only a reaction to the horrors of slavery. It was a statement of empowerment, defiance, and a challenge to the societal power structures of the Antebellum South. So, when we look at these sources, we are gaining a window into a really crucial moment in someone’s life. Whether their escape was temporary or permanent, and whatever their unique push factors may have been, this moment of transition embodied self-actualization. In my opinion, viewing fugitivity solely as a reactive by-product of slavery strips fugitives of their agency and obscures the political nature of fugitivity. We might never know what came before or after, but in these historical snapshots we can try to make sense of not only who the fugitives were, but also what motivated them to escape. I still think fugitivity is massively misunderstood. There is a lot of research that still needs to be done.

ZBF: Since the Fugitive Slave Database allows us to explore historical narratives through statistical profiles, I am fascinated by its potential as a body of knowledge which combines the arts and the sciences. Has your work inspired any other interdisciplinary inquiries?

SW: As a social historian, I always want to prioritize human stories and experiences. However, when building and populating a database with fixed variables, our profiles also need to be statistically sound. The combination of these two priorities allows the database to exist as an interdisciplinary body of knowledge which includes key values and features from both the arts and the sciences. Like many other digital humanities projects, this work pedals an approach which challenges the notion that academic research must be either qualitative or quantitative. By using statistical methodologies to investigate thousands of micro-histories, we allow ourselves to ask questions that can be both extremely specific and extremely broad.

Let’s say that I’m using the database to research gender. If I want to construct graphical models for the gender distributions of all recorded fugitives in Maryland and Georgia from 1790 to 1810, I can generate these findings. But I can also investigate which types of adjectives were predominantly used to describe fugitives of different genders. Perhaps I could look into whether enslaved men were described as “artful” more often than enslaved women. This may lead me to theorize about how slaveholders in Maryland and Georgia perceived and treated enslaved women differently than men, which could inform historical research into the diverse experiences of enslaved individuals in the Antebellum South.

Since the database lends itself to so many different fields, I’ve also had students approach me with their own specific interests. One of my students was interested in art, so she looked through all of the data entries where fugitives were described as musical (i.e., “plays the fiddle”). Interestingly, she found that many of these individuals were listed in the advertisements for above-average reward amounts. One fugitive from Maryland named “Mike,” for example, was described as “Very fond of playing on the fiddle.” His owner took out 108 ads for him in total, publishing the same notice nearly every single day for several months in 1806.

These findings could lead us to question how some slaveholders may have valued fugitives differently based on their creative abilities, as these comments are at odds with the traditionally dehumanizing nature of these sources. We can also look into musicality as a presentation of rebellion and agency, since some enslaved individuals stole their masters’ instruments when they escaped.

These are only a few examples. I’ve had other students approach me with their own ideas, and it’s been great to see how the database fits into a broader story of people using these types of projects to better understand history.2

ZBF: How do you see your database being used in the future?

SW: From the very beginning, this database was designed with the idea that it would become an accessible resource for anyone to use. My long term goal is to eventually have an online presence that can be accessed for free. We’ll definitely have to do some fundraising to get it up and working, but someday I want people to be able to dive into the database themselves and look for their ancestors. I would love for people from diverse fields and disciplines to incorporate this tool into their work, since there are still so many variables in the database that I have not studied in detail. We’ve got a really fantastic resource on our hands, and I’m not a believer in keeping this type of work to myself. These findings should be made accessible to anyone who wants to join us in reviving the stories of empowered men and women who rebelled against a system intent on commodifying them. For me, this is what history is about.

Wallace’s chapter (titled “Artfulness, Performance, and ‘the other’ in Advertisements for African and African American Fugitives in the Early National United States”) in American Cultures as Transnational Performance (ISBN: 9780367501310) is now available for pre-order.

Wallace’s In Pursuit of Freedom: Enslaved Runaways and Resistance in the U.S. South, 1790-1860 is forthcoming with the University of Georgia Press https://ugapress.org

Endnotes

1. This statement excludes repeat advertisements, which occurred when the exact same notice was taken out more than once. —ZBF

2. Dr. Wallace has written two pieces recently about his database: one is about how the database can be used to study fugitivity through a performance studies lens, and the other concerns digital methodological interventions when studying fugitive slave advertisements. The breadth and depth of Wallace’s work is exemplified in these two pieces, as they were written for such distinct fields yet both draw from the Fugitive Slave Database. —ZBF