Written by Marcus Loiseau

Edited by Frank Lukens '22 and Larissa Jimenez '23

Kreyol pale, kreyol komprann.

Que Dieu bénisse my country et le monde

Abstract:

This thesis demonstrates the legacy of the U.S. Occupation of Haiti through the dynamic historical scope of the Harlem Renaissance and Négritude Movement. These two major cultural and literary movements unequivocally transformed the discourse about racial equality, black identity, American democratic values, and modern black transnationalism. The actors and sources highlighted in this essay centralize the influence of Haiti and the U.S. intervention in the country to further the narrative that this dynamic historical event had major symbolic implications on the black world. Additionally, the scholarship affirms the fact that one country can inspire a whole racial group to mobilize and unify by virtue of cultural similarity, intellectual veneration, and most importantly, commonalities in experience--specifically as they pertain to systemic oppression.

Introduction

Haiti was the first black republic in the world, broadcasting to the predominantly white Western-dominated international system the structural power of black mass resiliency, tactical acuity, and democratic spirit. This paper argues that the U.S. occupation of Haiti inspired newfound intellectual connections between Harlem Renaissance and Négritude writers, who, despite their linguistic differences, connected on bonds centered on a common racial heritage and vision for equality. In doing so, my essay will first contextualize Haitian history in the post-Revolution period, illuminating the profound intellectual connections between the leaders of the first black Republic and the American abolitionist movement. The Haitian Revolution, as literary sources show, emboldened the moral and rhetorical calls for racial equality in a hemisphere and world which unabashedly questioned and viewed with contempt black self-worth and achievements. Following this introduction, my paper will provide the policy justifications for the U.S. occupation of Haiti, the considerable backlash from black rights advocates in America and the burgeoning growth of black transnationalism soon after.

Throughout the decades preceding the Haitian Revolution, African Americans, who were also forcibly dispersed or oppressed by white Americans, intimately empathized with the diplomatic and economic struggles of Haitian people. Although African Americans and Haitians have had friendly historical ties since the birth of the Haitian republic, the U.S. invasion of the black-governed island nation fundamentally expanded the intellectual the relationship between Harlem Renaissance authors, most of whom were African Americans, and black Négritude writers, who came from French-speaking countries like Haiti, Senegal and Martinique. This historical thesis contends that the 19-year U.S. occupation of Haiti ( 1915-1934) strongly fueled the social sentiments pertaining to racial inequality, economic marginalization and Western imperialism that influenced the later ideological basis, as it pertains to Pan-Africanism, of two major cultural movements: the Harlem Renaissance, which took place in New York City from the early 1920s to the mid 1930s, and the Négritude Movement, a French-based black-focused literary movement between the 1930s and 1940s. Additionally, America’s imperialism renewed and fortified two vital aspects in the interactions between preeminent black actors from both respective cultural movements: the sense of intellectual and rhetorical solidarity as well as the generational commitment towards greater economic and racial equity for black people around the world.

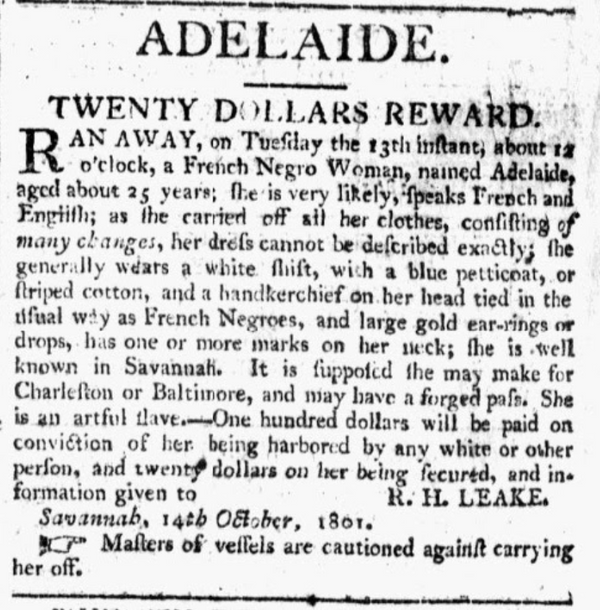

I. Pre-Occupation (1804 - 1915): Haiti as a National Model for the Black World

Since Haiti declared its sovereignty on January 1, 1804, free African Americans have seen the predominantly black nation-state as a representative of genuine democratic values--unlike the claims of other governments during the Revolutionary period. As the editor of The Colored American, a weekly newspaper published and circulated in free communities of color in the Northeast U.S., commented in 1836, “in morals and in literature, Hayti takes the lead of all South American Governments…[Haiti] will compare with our own, at the same age of independence.”1 Haiti’s model for democratic governance and independent black society was celebrated by the freed black world because it took place in an era in which the enslavement of Africans was not only morally and religiously justifiable, but also was the foundation for various labor and economic systems throughout the globe. The newfound independence of the black populace in Saint Domingue would unequivocally dismiss various Eurocentric notions about the lack of leadership capability and resolution of the whole black race. In defeating their French oppressors, Haitians marked a new chapter for the arguments of anti-slavery advocates and the self-esteem of African slaves around the Americas. William Watkins, a black abolitionist and editor for the Frederick Douglass Papers, proclaims that the country “will furnish an irrefragable argument...the descendants of never were designed by their Creator to sustain an inferiority, or even a mediocrity, in the chain of beings.”2 The will and power to strategically coordinate against enslavement of African peoples in Haiti affirmed that rhetorical fragility of pro-slavery advocates in the Western world. Despite their lack of consistent contact, black intellectuals from Haiti and America concurred against the prevailing presuppositions of white supremacy as it related to legal rights of black people. This enlightenment not only psychologically empowered--mostly freed--African Americans back in the U.S., but it also initiated a social connection between Haiti and the larger black world. Haiti would come to represent the aspirations of marginalized men and women facing the burdensome shackles of slavery, racism, and social exclusion.

African Americans admired the self-deterministic and democratic values of the formerly enslaved Haitian people so much that they launched emigration campaigns in which thousands of educated, financially stable, and/or freed people of color fled to Haiti. Generations later, African American immigrants not only successfully integrated but also became high-ranking leaders in Haiti’s most powerful institutions. For example, Prince Saunders, an African American educator, served as the Attorney General in President Jean-Pierre Boyer's administration.3 Just as Jamestown, Virginia, was a “new world” to English Protestants, so was Haiti to the disenfranchised and financially restricted African American population. Haiti offered political freedoms that the United States could not offer. Furthermore, Haitian political elites like President Boyer, the country’s second President explicitly embraced this immigration, stating that the country was a sociopolitical promise land, or symbolic asylum, for all the African diaspora.4 New African American immigrants earned political rights, racial dignities and unparalleled economic opportunity that had been unprecedented in Europe or other parts of the Americas. Haiti’s diplomatic positioning as an anti-colonial and anti-slavery nation near to American shores meant that black Americans would not only gain constitutional rights, but they could also potentially thrive in a society morally congruent with their own political values. In Haiti, an African American man could receive the natural rights that he was denied in “democratic” nations in Europe and the rest of the New World. The equality and freedom Haiti’s institutional leaders gave African Americans essentially reinforced the credibility of a relationship which would eventually be structurally tested during the later U.S. occupation.

II. Occupation (1915 - 1934): The Justifications for American “Assistance”

In the period preceding WWI, American intervention throughout Latin America was considerably dictated by geopolitical and economic positioning against the world’s major military powers. As a result, the 1915 U.S. intervention in Haiti was “justified” by policymakers who focused on Haiti’s multi-decade political instability and Germany’s growing economic influence in the region. Similar to the way Cuba was viewed in the 1950s, American foreign policymakers viewed Haiti as both a strategic point uniquely vulnerable to Germany, an American foreign policy adversary, and as a country of financial value for the powerful class of American investors. The perceived threats to American national security was also understood by the period’s robber barons as merely a chance to profit off international misfortune.

Haiti's executive branch indeed had shown longstanding structural challenges which created opportunities for manipulation by foreign and domestic forces. Between 1853 and 1915, 22 different men, using either military force and/or politically nefarious means, assumed power in the Haitian territory.5 American interventionists who believed that the hemisphere’s micro-political instabilities created potential vulnerabilities, which could be exploited by Europeans, felt increased pressure to intercede in the critical political, fiscal, and military institutions serving Haiti--and other Latin American nations. In the century that fortified gunboat diplomacy and the Monroe Doctrine, which continued the U.S.’ hemispheric hegemony over unstable Lain American countries, Haiti--an ill-protected country near America’s shores (700 miles away)--inevitably would be forced to receive American assistance. This “assistance” ultimately showed to have insurmountable costs, including the restructuring of laws to favor Western (mostly American) occupants, the strengthening of Social Darwinist notions, and the economic disenfranchisement of Haitians. American lawmakers were fearful of their geopolitical and financial investments in the country, as well as the domestic national security threats to the U.S. mainland posed by German-Haitians and their connection to the German Empire. In 1910, German-Haitians, who intermingled with native wealthy elites in an effort to legally own assets, comprised only 200 people who controlled 80% of Haiti’s international commerce.6 Many policymakers in various U.S. presidential administrations of the early 20th-century were alarmed by German presence on the island because diplomatic tensions between the U.S. and Germany were abnormally high. Additionally, German Kaiser Wilhelm II was interested in using the Port of Saint-Nicholas Mole, on the northwest tip of the island, as a naval base for his empire. In the age of German militarism, American officials feared they would be seen as weak, capitulating to German interests in the global arms race if they did not respond to what their allies viewed as Prussian encroachment in the Americas. To make matters worse, Germany was playing a strong role in financing and influencing other foreign revolutions, including the Haitian Civil War of 1912.7 Junker aristocrats, who were monarchy-supporting and landowning elites, led the German foreign policy apparatus and staffed its military, to further augment German power. Junkers would fuel the notions which suggested the German military threat was literally never too far away. Americans deeply worried that German power in Haiti would come at the cost of American financiers, and most importantly, the safety of U.S. citizens. Thus, U.S. intervention in Haiti was seen as advantageous not only for imperialists and profit-seeking businessmen, but also for the parties who feared the possibility of diplomatic and military German aggression, especially in Latin America. These multitude of reasons combined with the racial sentiments of the era made an action which would symbolize U.S. imperialism in the black world seem strategically appropriate.

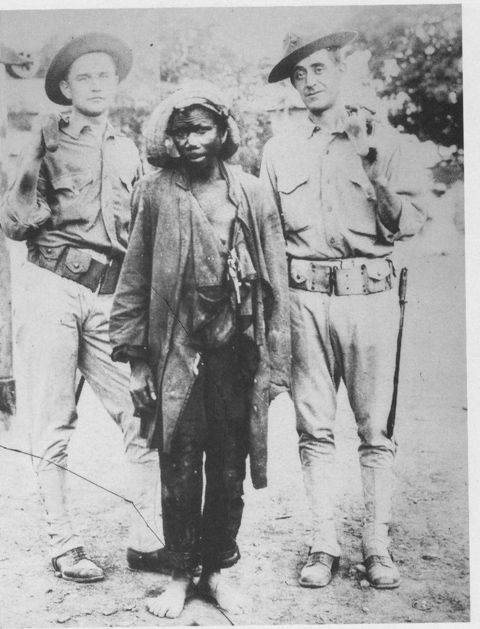

The Underlying Motive for Occupation: There is No Imperialism Without Racism

In the late 20th-century, people of Anglo-Saxon descent internalized both the philosophical premise of The White Man’s Burden and scientific racism. Discriminatory racial notions not only influenced the marginalization of racial minorities domestically, they were central to U.S. foreign policy abroad. World’s Work, a pro-business American magazine, asserted that Haiti was a natural paradise ruined by its predominantly black inhabitants, who were “inherently filthy and lacked moral acuity.”8 Therefore, in the eyes of white Americans, disregarding the sovereign rights of Haitians was appropriate simply because the inhabitants of the country were identifiably black. U.S. Marines, especially from the South, despite coming in to “restore order,” transferred their racist worldviews and violent behavior to Saint Domingue, the island comprising both Haiti and Dominican Republic (which was occupied 1 year after Haiti). Less than 6 months prior to the American invasion, D.W. Griffith’s silent film, The Birth of a Nation, which depicted white people as virtuous heroes and black people as futile criminals and sexual predators, was released and commemorated by the White House’s chief executive, President Woodrow Wilson. Thus, in support of the values of American society and commander-in-chief, many white soldiers traveled to Haiti proudly reflecting the Post-Bellum racism accentuated by the movie. These soldiers earnestly believed their mission in Haiti and treatment of the country’s citizens was, indeed, altruistic, like the film’s so-called protagonists. Additionally, when troops entered the island, the Klu Klux Klan, an organization whose central identity is based on racial hatred and discriminatory violence toward African Americans, was widely accepted among political and social circles all over the states.9 Unsurprisingly, the influence of the Klan’s ideology motivated U.S. troops to treat Haitians with the same homegrown racist disdain as they did to African Americans in the Jim Crow South: committing sexually violent acts towards women, intentionally segregating themselves from the black populace, and killing men and children with minimal justifications. Marines, who had initially intervened to quell the geopolitical fears of white American policymakers and provide political order in Haiti’s executive office, became the prime instigators in the country’s institutional violence and newfound racism.

Black writers acknowledged the heinous conducts of U.S. troops and utilized their occurrence in their larger struggle against colonization and racial discrimination by Western forces. These foreign forces had racially and socioeconomically fractionalized societies in their various (former) colonies. Due to ingrained perceptions of black people, some Marines had arrived in Haiti “ready only to do battle with a racial enemy.”10 Indeed, the central focus of some military members was not to stabilize Haiti politically. As the mission plan had originally stated, it was to fight against what they saw as “violent and disruptive black people.” The race-based sentiments held by policymakers and military personnel is central to comprehending why the U.S. foreign policy itself was an instrumental impetus for black men and women from all over the world to formally collaborate, under the symbolic banner of black internationalism. Unanimously, all understood how racism had transformed and impacted nearly every institution in their societies--justifying their unequal treatment, as well as, limiting their holistic potential as a group. Colonial rule in Haiti was yet another structural test of black resilience that would be met with dialectical vigour on the global stage.

The Weldon Johnson Report: Lobbying for Haiti’s Freedom

When U.S. Marines invaded Haiti on July 28, 1915, African Americans were among the first foreign groups to provide moral and rhetorical support to the beloved island nation. As news about the inhumane actions of the Marines came back to the U.S., Afro-American civil rights leaders began to mobilize to contend against America's military presence in Haiti, the subsequent harsh treatment of fellow black people, and the policy justifications provided by the Wilson administration. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and its leaders, such as W.E.B Du Bois, adamantly lobbied against the occupation by publishing newspaper articles, persuading Republican lawmakers to disavow the foreign policy, and connecting other black intellectuals who indisputably opposed any form geopolitical and economic hegemony. James Weldon Johnson, a Jacksonville-born civil rights activist/lawyer and Harlem Renaissance writer with Haitian ancestry, was employed by the NAACP to investigate the impact of U.S. ground forces on the island and their behavioral conduct towards the black citizenry. His previous foreign policy experience as President Roosevelt’s appointed consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua made him the optimal candidate for the investigation. Johnson asserted that coupled with their nonchalant conversations about torturing Haitians, “brutalities and atrocities on the part of American marines have occurred with sufficient frequency to be the cause of deep resentment and terror.”11 Like European imperialists, American troops gave little to no value to the lives of non-whites in the order of the racial caste system. Under this thinking, black people, no matter their place of origin, were regarded with the same inferiority abroad and in America. Military members, emboldened by the impunity of their actions, killed civilians without cause, further alienating the country's people, both wealthy and poor. Johnson points out that their reasoning was simply based on “pacification...which means hunting ragged Haitians to the hills with machine guns.”12 Those being “hunted” were farmers and children, who, maintaining the revolutionary history of their ancestors, fatally tried to confront their adequately armed foes. These groups of rural rebels called the cacos, armed with 19th-century guns and agricultural tools were captured, tortured, and slaughtered; however, their Mackadalian sentiments would be continuously celebrated by community-members and black foreigners alike in their struggle against neocolonialism. Weldon’s research enlightened both his targeted population, African Americans, and Négritude writers, who, coming from the French-ruled developing world themselves, were intimately aware of resistance campaigns by rural insurgents (in their own countries) and the logical contradictions of Western imperialism. Considering white lynching of black men was considerably high in the U.S. during this time period, ethnic sympathy for foreign minorities, who were victims of organized white violence, was strong among the Afro-American community. Weldon’s writings informed people of color around the world about the true severity of the calamity taking place in Haiti. The publicity of Weldon’s 1920 report titled “Self-Determining Haiti” would be the great awakening for African American readers who were unaware of their nation’s foreign policy in Haiti and its resemblance to Jim Crow laws in Southern states. Weldon made sure to highlight the crucial commonalities and virtues which have historically shaped the dynamic between African Americans and Haitians. In an article he published called “The Truth About Haiti,” Johnson asserted:

The colored people of the United States should be interested in seeing that this is done, for Haiti is the one best chance that the Negro has in the world to prove that he is capable of the highest self-government. If Haiti should ultimately lose her independence, that one best chance will be lost.13

In the eyes of Johnson, leading the anti-occupation efforts in Haiti had a larger significance than just diplomatically assisting and protecting a poor country in Latin America from U.S. interests. The Haitian anti-occupation movement was a historical posturing of black solidarity in a nation that symbolized that very principle for the greater black world. Johnson’s commitment towards Pan-African solidarity after his travels to the island was passed on to many of his later Harlem Renaissance literary contemporaries like Langston Hughes, who would later travel to Haiti in the midst of the occupation, meet with other black intellectuals abroad, and depict the characters and experiences pertinent to Haiti in their works. Given the fact that his documented experiences urged Afro-Americans to travel and personally witness the jarring realities taking place in Haiti (and other predominantly black countries), Johnson became a unifying intermediary, central to the relationship between actors from both the Harlem Renaissance and Négritude Movement.

The (Re)-Emergence of Black Transnationalism in 1919

After the invasion, the black cultural and political world was re-energized against the generational struggle maintaining Western-fueled neocolonialism. Certain activists from Africa and around the world had consistently campaigned against imperialism and racism, but their efforts were largely focused in their specific homelands, rather than the greater black community. Within four years of U.S. Marines landing in Haiti, W.E.B. Du Bois organized the first meeting of the Pan-African Congress in February 1919, with various civil rights and intellectual leaders from all over the black world speaking about the exploitation of the continent and its former peoples.14 This event was a focal point for the social and intellectual history of Pan-African Movement because it was the first occasion when principals from both African and African diaspora communities had officially assembled for the purpose of addressing imperialism and its limitations on black people. In 1921, in the early phase of the Harlem Renaissance, the Pan-African Congress formally re-convened in London, with representatives from 26 countries, including Haiti. The Congress agreed upon an issuance that denounced the present state of racial affairs and the subsequent need for a fairer distribution of the world’s resources.15 In light of the fact that early Harlem Renaissance intellectual and artistic expressions had been taking place in the same year, the world was undergoing a racial upheaval characterized by political justice within the international order. The spectrum of social experiences of representatives in attendance would add experiential depthness to these black international exchanges, which would collectively further the objectives of all colonized or socially marginalized citizens, regardless of if they were located in the U.S., Haiti, or anywhere else in the world. In many ways, W.E.B Du Bois showed the souls of black folk around the world could galvanize through common tribulations of pain, sorrow and rejections, in the grand pursuit of civic equality and happiness.

Harlem Rennaissance: The New Negro Movement is Born!

The Harlem Renaissance was a period of black artistic expression, in which various social, political, and intellectual actors convened in New York City to highlight the nuances of racial expression in America and illuminate African American artistry. Between the early 1920s and mid 1930s, African Americans who had fled the South to the North during the Great Migration began to create their own communities dominated by philosophical notions countering Jim Crow-based segregation and white supremacy. The Harlem Renaissance placed high value on the new negro, a term coined by Alain Locke signifying a race-conscious African American inspired by historical literacy and black cultural heritage.16 These black men and women proactively use their knowledge for racial progression in America. This is all whilst celebrating black cultural identity through the rhythmic jazz of Cab Calloway at The Savoy Ballroom, high tempo Lindy Hop dances, and avant-garde visual artworks by sculptors like Richmond Barthé. New Negroes were not only knowledgeable about Black history in America, but they were also cognizant of the achievements and structural impediments of black people around the world, just as Weldon Johnson had hoped. Considering 380,000 black veterans had just returned home from World War I frontlines after successfully defending democratic principles abroad, they felt a renewed sense of deservance and patriotic determination in their fight to fully gain rights promised in their own constitution.17 This meant being treated fairly under the due process of law in America’s judicial system; being able to vote without threats from race-centered government restrictions (like poll taxes and literacy tests) or murderous terrorist groups like the KKK; and being economically freed from the involuntary servitude system that sharecropping had created. The new negro would shed blood and tears, not from the battles in France’s Somme River Basin, but through cultural self-expression in the urban streets of Harlem.

Despite being an American-based movement, many aspects of the Harlem Renaissance resonated with Haitian cultural identity. African Americans and Haitians would share both historical experiences and genealogy, since many of the movement’s leaders, like W.E.B. du Bois and Marcus Garvey, had Haitian or West Indian ancestry.18 Due to these connections in lineage, African American viewed Haitians as their Caribbean siblings with the same racial experience but different cultural and social history. Furthermore, New York City during this time had a vibrant Caribbean community composed of immigrants from countries like Jamaica and Haiti who immigrated to Harlem, which was frequently described as the “Negro metropolis.”19 Coming from racially homogenous countries and experiencing the worst of America’s racial caste system, many of these immigrants became politically engaged to combat systemic discrimination. The strong relationship which emerged between Caribbean immigrants and African American community members coupled with their pronounced cultural distinctions motivated Afro-Americans to be increasingly engaged about world issues--especially affecting the Caribbean region. Considering that many of the Harlem Renaissance’s most influential actors explicitly outlined the Haitian Revolution’s influence on their own artistic depictions and race-related worldview, the U.S. government's occupation would justify Harlem Renaissance leaders to unequivocally condemn American imperialism--and its related discriminatory impetus, whilst providing an opportunity to support a global Pan-African movement. The Haitian diaspora experiencing and contributing to the Harlem Renaissance movement in the U.S. would also link the ideas of this American literary revolution with later forming social movements like the Négritude. Both the Négritude and Harlem Renaissance Movement would consistently highlight the influence of Haiti’s historical events on their own revolutionary intellectual philosophies about race and culture.

The Emergence of the Negritude Movement: The Literature of Black Paris

The Négritude Movement, similar to certain themes in the Harlem Renaissance, was launched to celebrate black identity and counter the notions of “natural” racial superiority argued by Western imperial powers. Like Harlem Renaissance writers, Paris-living authors from Francophone countries, especially the Caribbean and West Africa, rhetorically delineated from popular views--in both black and white communities--highlighting their cultural ties to Africa and centralizing the celebration of black identity or blackness. This fundamentally contradicted the dominant and disseminated perceptions of Euro-American culture, which aimed to suppress the glorification of anything related to Africa. In the consciousness of the white world, one’s racial identity was synonymous with a person’s innate character and, in many cases, analytical capacity--and Africans and their diaspora naturally lacked the ability to think on their own or to the same levels as individuals with European descent. Thus, in justification of rebutting these racist views and literally capturing the similar experiences (or struggles) of black people, the Négritude movement was launched. The term ‘Négritude,’ as Aimé Cesairé, the poetical father of the French-written movement, states, was coined when “a few dozen Negroes..from Guiana, Haiti, North America, the Antilles came together in the Paris of the thirties,” to discuss the politics of assimilation--specifically Black/African identity in a world that despised anything related to Africa, black skin, and intellectual pride by people of color.20 Understanding of these topics, subsequently, brings forth cultural consciousness and pride, a characteristic hated by Europeans who saw the rest of the non-White world as uncivilized and, logically, in need of white intervention. White superiority towards people of color was widely accepted by not only Europeans but also by the people they controlled--who had grown up in a world violently shaped by Western culture and institutions. Understandably, the movement was an intellectual channel to rebel against white military and political control, as well as the prevailing European cultural hegemony, which completely disregards and/or minimizes the accolades of Haitians and other citizens of African descent. Négritudinists could articulate their particular experiences to highlight their commonalities with other distant intellectual movements, as well as, advance their passionate claims for racial justice.

The Influence of Haiti in the Negritude Movement: The Connection of Ideas & Experiences

Since the early beginnings of this movement, Négritudinists--if they were not already Haitian--had affirmed their deep deference for Haiti, and its respective historical contribution to black history. Cesaire was inspired by Haiti, so much so, that in his most famous poem, “Cahier d'un retour au pays natal,” he passionately claims in 1939, “Haïti où la négritude se mit debout pour la première fois et dit qu'elle croyait à son humanité” (Haiti where the négritude stood for the first time and said she believes in her humanity).21 In other words, the ethos of this 20th-century movement was first epitomized in 1791, when the anti-colonial insurrection on the island of Saint Domingue first began. African slaves attempting to be consciously recognized as humans (rather than mere commodities, beasts, or sub-humans) and gain racial freedom against their European oppressors fought back; whilst still maintaining and celebrating their African traditions (ex: voodoo). The significance of Haiti--and its symbolic ideals, provided Pan-African scholars, even prior to the commencement of the Négritude Movement, with clear justification to convene with other Afrocentric movements, like the Harlem Renaissance, even if the linguistic differences posed as a major communicative and cultural barrier. The amplification of Western encroachment efforts in Haiti (and in other black countries), as well as, the institutional defiance of members of the populace provided contextualization and purpose to differing cultural literary movements, which, in spite of their geographic fluctuations and ideological contrast, celebrated black identity and cohesion. Rabaka contends:

The new, even more radically cultural and artistic movements found foothold, first, in the United States, then in Haiti, and finally in Paris, where French-speaking black students from Africa and the Caribbean, enamored with the innovations of the Harlem Renaissance and the Haitian Renaissance, established their own distinct version of black radical cultural and artistic movement: le mouvement de la Négritude. 22

The black youth of Francophone countries traveling and studying in Paris became intellectually invested in historical events related to imperialism and its consequent interaction with race in their respective motherlands. Race discrimination was universally comprehensible for Anglophone and Francophone black writers alike, since their lives had at every single minute been impacted by their racial identity or, as W.E.B Du Bois would desribe, double consciousness. Césaire writes that “the dominant feeling of the Negro is the feeling of intolerance. An intolerance of reality because it is sordid...from dark heavy dregs of anguish, of suppressed indignation.”23 Whether a poet came from Haiti, Martinique, Senegal or even the United States, they had endured the everyday minutiae of living in an inequitable society, directly, because of the limitations posed by their skin color.

In light of American subjugation, Haitian thinkers became closer aligned with their contemporaries in Africa. Leon Francois-Hoffman, a French essayist on Haitian history, argues that “as then treated as underdeveloped natives, Haitians had to face the fact that their fight for independence and national dignity had much in common with that of their African brothers.”24 This meant an unequivocal racial collectivity in which the discourse about American imperialism in Haiti was viewed in the same moral and legal light as French colonialism in Africa. Parallel to their ancestors (or the cacos), these Négritude students waged war against white oppression with their weapons being essays and poems that artfully commemorated their African heritage.

Le Generation De L’occupation: The Representation of Haitian Suffering in Poetry & Literature

America's imperialism psychologically triggered Haitians to symbolically rebel through a literary revolution meant to galvanize the masses of African-descent citizens in the intellectual struggle against Eurocentrism, colonialism, and racism. As Damas, a Négritude poet from French Guiana, argues, “l’occupation américaine provoqua chez l’Haïtien un ébranlement dans l’ordre psychologique. Cette crise profonde détermina dans les diverses couches de la nation une révolution dans l’ordre moral qui donna lieu à la création de foyers de résistance.”25 Despite the country’s long-standing social and political discord in Haiti, foreign control had invariably unified the nation’s conflicting political groups and social classes, whilst affirming the cultural identity of Haiti’s revolutionary people abroad. Upper-class Haitians, who as James Weldon Johnson had observed, were treated as second class citizens by less educated and poorer U.S. troops. Their travels to Paris afforded them with the free speech right and literary capability to document the socio-politico caused by American troops, who had, indeed, transformed Haiti and its very meaning to the world. Haitians thinkers of the time era, also known as le generation de l’occupation (“the occupation generation”), began to travel abroad--especially to places with established Haitian communities like New York City and Paris, emphasizing: the harsh treatment of ordinary people by American troops; some of the Afrocentric cultural and literary movements developing in Haiti like l’indigenism and l’africanism; and the need for cross-cultural unity. Furthermore, they would highlight the press censorship and jailing of radicals by the U.S. military officials to curb the frequency of street protests.26 Their voices would be used as microphones, further publicizing inequities in Haiti directly tied to American imperialism.

Langston Hughes, the Harlem Renaissance's most famous poet, was persuaded to travel to Haiti by fellow civil rights leaders Walter Francis White and James Weldon Johnson. Thus for 3-months, in the late years of the occupation in 1932, Hughes poetically elaborated on his wide-ranging observations in the island nation. He stated that “Haitians who had lived abroad know all the steps of Broadway and of Paris…[however, Haitians] seem to remember Africa in their souls.”27 During his travels, Hughes observed that, despite the fact that some Haitians were educated and well-traveled, much of the country’s cultural characteristics--like Kreyol (an Africanized patois of French spoken in Haiti), Haitian Vodou, and dances--were derived from African traditions. Hughes saw that, in spite of the historical difference, his own admiration and affinity for a country so Africanized meant that cultural unity among Negritude writers and their Lenox Avenue-based counterparts was certainly possible. The most important commonalities re-energizing scholars from both movements was the centralization African identity in intellectual discourse and the crisis in Haiti. Haiti was no ordinary country for Langston Hughes (and other Harlemnites), as Hughes said in his autobiography, “I had read of Toussaint L’Ouverture, Dessalines, King Christophe, proud black names, symbols of a dream--freedom--building a citadel to guard that freedom.” 28 Haiti for so long had embodied black freedom and leadership--for people around the world; however, with the--dominating--presence of American military and financial interests, Saint Domingue was anything but free. On a metaphorical level, this meant that blacks around the world were seemingly hegemonized by Western imperialists, and if not politically mobilized and unified, would continue to live in an inequitable nightmare. As one historian puts it, the occupation of the island nation became the prise de conscience (“wake up call”) in the Negro world; therefore, much of the concepts of Negritude movement grew out of the events taking place in the country.29 Langston Hughes would hear the “wake up call,” with the same attentiveness as Caribbean and West Africans writers, who also had been generationally marginalized as well as culturally despised by Frenchmen. Haiti served as the symbolic bridge of the black world, linking the superbly innovative Harlem Renaissance minds of the U.S. to brilliant black French-speaking icons in Africa and the Caribbean.

Equality For All: The Proactive Leadership of Women in the Negritude Movement

In the midst of the Occupation, various Haitian-based publishers became the prime linkage to disseminating information abroad about everyday life in the presence of the American military and introducing different parties from both movements. These daily or weekly newspapers gave an international voice to Négritude poets, musicians, and novelists that would be well-received across the Pan-African world--even among English speaking Harlem-based intellectuals. In terms of reach and influence, no Haitian-founded newspaper informed readers about African identity and the Haitian crisis like the La Revue du Monde Noir (“The Review of the Black World”), a publication co-founded in 1931 by Dr. Leo Sajour, a Haitian writer, and Paulette Nardal, a Negritude poet and writer from Martinique who had aspired to linked black writers from Harlem and Paris to:

Donner a l’elite intellectualle de la Race noire et aux amis des Noirs un organe ou publier leur oeuvres artistiques, litteraires et scientiques.Etudier et faire connaitre par la voix de la presse, des livres, des conferences ou des cours, tout ce que concern la CIVILISATION NEGRE.30

[give to the intellectuals of the black race and their partisans an official organ in which to publish their artistic, literary and scientific works. To study and popularize, by means of the press, books, lectures, courses, all which concerns NEGRO CIVILIZATION.]

Bearing in mind the Occupation, RBW writers would depict social intricacies in both the U.S. and other “negro civilizations” using the combination of black transnational news and humanistic literature, which had yet to be done. Furthermore, it should be noted while the content in this syndication was revolutionary, the mere fact that the publication had presented each page in both English and French affirmed the conscious goal of amplifying cross-cultural communication between intellectuals whose most pronounced social barrier was their differences in native language. The fact that these highly educated black women led and edited the magazine showed that, in some ways, the Occupation also provided a newfound opportunity to black women from both the Anglophone and Francophone world to strengthen intersectionality, that is women’s rights and sexuality, in discourses that were largely male dominated. Paulette Nardal would go on to inspire a generation of leaders being a successful feminist writer and first black person to graduate France’s prestigious Sorbonne University, but her journalistic contributions to both literary movements remains one of her greatest achievements.

The Economic Interests of a Few Above the Marginalization of the Many

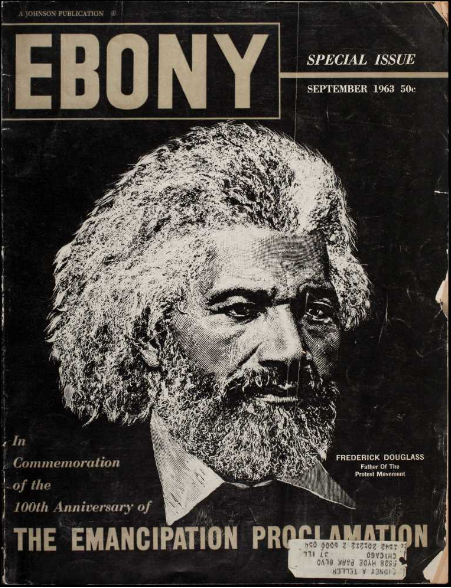

Financial interests of American commercial investors posed as major forces for the aggressive and controlling U.S. foreign policy in Haiti. U.S’ economic investments in the Caribbean were seen as instrumental for the nation's overall economic development and output. As aforementioned, American business interests were particularly influential to the formulation of the State Department’s policy frankly because they undermined the significant Franco-German influence in the country and it would expand on the continuance of American economic satellite states (ex: 1930s Cuba).31 To writers coming from West Africa and the West Indies, which had virtually parallel economic systems, this diplomatic justification for economic exploitation was all too familiar. Additionally, the occupation itself was disproportionately worsening the population’s most economically vulnerable groups, black peasants and farmers. Hughes argues, “All the work that keeps Haiti alive, pays for the American Occupation, and enriches foreign traders--that vast and basic work--is done by Negroes with no shoes.” 32 American investors were the neocolonial versions of French and Antebellum Southern slave-masters, profiting from the work of the disenfranchised black populace. Hughes was witnessing an inconsumable reality, the U.S. intervention had reversed not just the economic progress of Haiti, but for all people of African descendants, who, unanimously, had perceived the country as the best representation of black economic autonomy. The Gendarmerie went to insofar re-establish a colonial corvée law that forced peasants to either build roads or pay a tax, which most could not even afford.33 This demonstrated how neocolonialist were willing to establish a morally-contested system of modern-day slavery for the sake of profit. Johnson during his NAACP-centered voyage witnessed a corvée raid, citing, “[Marines] seized men wherever they could find them, and no able-bodied Haitian was safe from such raids, which most closely resembled the African slave raids of past centuries. And slavery it was.”34 One can imagine that these series of events not only traumatized everyday Haitians but they also had a profound effect on African Americans and Négritude writers who engaged in this truth--and the notions it raised about threats to their own lives. Unfortunately, Haiti wasn’t the only country in which citizens were being coerced to work by foreign powers, this was largely the framework of labor in many other countries, especially as the French and other European powers scrambled for Africa. Thus, writers from each movement had an moral linkage considering the extreme labor practices that commodified the ancestors of Harlem Renaissance writers, before the issuance of the emancipation proclamation, only 53 years prior to the commencement of the American intervention were, indisputably, revitalized in the lands of Négritude writers in present-day Hispaniola and French West Africa.

The refusal of Europeans siphoning Haiti’s domestic capital and sovereign budget acted as another unanimously-agreed worldview for well-educated black people from both movements, especially for Négritude writers who, in nearly all cases, had come from financially privileged backgrounds. Leopold Senghor, a preeminent Négritude poet and son or a wealthy businessman, inspired by the adverse fiscal effects of neocolonialism in Haiti and Africa, said in his 1945 poem, “Prayer for Peace,” that:

The Great Tax Collectors have used for seventy years

To fatten the Empire's lands

Lord, at the foot of this cross - and it is no longer You

Tree of sorrow but, above the Old and New Worlds,

Crucified Africa,

And her right arm stretches over my land

And her left side shades America

And her heart is precious Haiti, Haiti who dared

Proclaim Man before the Tyrant

At the feet of my Africa, crucified for four hundred years

And still breathing

Let me recite to You, Lord, her prayer of peace and pardon 35

Africans and the African diaspora, all had been financially drained of their vast resources, or “tax,” while whites accumulated generational wealth from the subsequent crucification of these aforementioned people. Although Haitians had revolted in the forms of insurgencies led by slaves (1791), the country was eventually seized and structurally deprived by ‘The Great Tax Collectors.’ In the specific case of Haiti, the National City Bank of New York (NCBNY), in coordination with the United States government and military, took over the nation’s customs house to stop payments to public employees/servants whilst literally carrying out $500,000 worth of gold from the Haiti’s reserves to be transferred the bank’s vault on Wall Street.36 Although the country still had a viable economic hierarchy, Haitian intellectuals--which had solely come from elite families--were well aware that much of their own wealth could be effected, if not, confiscated by U.S. forces. Certainly, these institutional actions could have been argued on sovereign legal grounds; yet, they were not because elites who had authority before the occupation soon became politically powerless or complacent after the implementation of coerced policy reforms. The occupation reminded writers and intellectuals, despite their current place within the social stratification of their respective countries/societies, the nature Western imperialism meant their status--unlike their white counterparts--was invariably susceptible to change. The institutional events that happened in Haiti only evinced the notion that without unity on matters related to personal and sovereign wealth, intellectuals from both movements, who nearly always came from privileged backgrounds, were themselves subject to wealth eradication or job loss by under the prevailing economic order. Without holistic changes in action and thinking, colonial history, in their view, would continue to be an amalgamation of forewarnings.

III. Late to Post-Occupation (1934 - Present-Day): The Romanticization of Marxist Perspectives

In response to the financial and political impediments of the U.S. intervention, various radical voices in Haiti adopted Marxist worldviews during désoccupation and the post-Occupation years, impacting both their literary style and acceptance of communism. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 changed not only Eastern Europe but the whole world. Many citizens of African descent, naturally, viewed themselves as the global proletariat and their struggle as a class conflict--since race and class during this era were intrinsically linked. Karl Marx, himself, in 1867 book Capital stated that “every independent movement of the workers was paralyzed as long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the Black it is branded.”37 In other words, the global labor struggle could not be realized unless black people from around the world were freed from slavery, or other forms of economic abuse and disenfranchisement, which characterized neocolonialism.

Roumain & Hughes: A Literary Friendship with Ideological Connections

Due to the disproportionate wealth inequality and the strong influence of American bankers, some Haitian Négritude writers adamantly supported socialist/communist doctrines on the island and abroad. Jacques Roumaine, a poet and writer educated in Switzerland and France, was a central figure in introducing communism in political discourse.38 In spite of his land-owning familial background--like men from the intelligentsia, Roumaine was a staunch socialist, analyzing the hardships pertaining to American imperialism and the struggles of the black peasant class through the lens of Marxism.The emergence of communism--and its linking principles of egalitarianism (no matter race) and class unity aroused a newfound sociopolitical opportunity for Afro-Caribbeans, who had lived through intolerable external political dominance, economic exploitation and American-style racial segregation, to connect with fellow African Americans and their Francophone peers. Roumain points this out in his 1937 article, "La Tragédie haïtienne," for Regards (a left-wing French newspaper), saying that “the soil no longer nourishes these black peasants, these persistent workers, of whom it suffices to quote the magnificent title they bestow upon themselves, gouverneurs de la rosée (masters of the dew), and to describe the deprivation and pride with which they experience their destiny.39 Roumain, who would later host other French-speaking poets and Anglophone poets like Langston Hughes (prior to his trip to Russia), in asserting that the land--which symbolized power in Haiti--became virtually worthless, furthering the need for communal social ownership, instead of being controlled by an elite few--comprised of government officials, bankers, and businessmen. Whether in the U.S. or Haiti, lower/working-class racial minorities were being exploited and discriminated against in the labor market for greater profits and to industrialize their nations. In his 1933 essay “Negroes in Moscow: In a Land Where There Is No Jim Crow,” Hughes argues:

The Negro workers are so well absorbed by Soviet life that most of them seldom remember that they’re Negroes in the old oppressive sense that black people are always forced to be conscious of in America or…[the] colonies…[Russians are sympathetic] to the widespread and difficult struggles of the peoples of the capitalist lands where they are subjected to exploitation and oppression as serfs and colonials.40

This comparison of the lives of black people in the Soviet Union versus other black people around the world truly shows how substantially different--and specifically better--the social experiences of the USSR-living black diaspora was compared to their foreign counterparts. While Russians had moved to transform their society away from feudalism, in countries like Haiti, citizens were being used as neocolonial serfs in their own sovereign states. New Negro and Negritudinists would--in philosophical concurrence--show a distinct penchant for Marxist-centered perspectives, simply because of their systematic marginalization as a result of deeply race-influenced systems of capitalism.

In a show of intellectual deference and ideological commonality, Langston Hughes in 1947 translated in English and published Roumain’s most famous novel, “Gouverneurs de la Rosée,” a socialist-inspired realist novel written in 1944 about the class solidarity and the political frameworks exacerbating poverty-stricken Haitians. Contextualizing the late and post-Intervention time period in Haiti and the world, it’s evident that despite the formal reduction of American troops from Saint Domingue, Western-based policymakers and financiers still, disproportionately, influenced the Western hemisphere’s economic resources, succeeding governmental administrations, banks, and to a larger degree, its poor black populace. Alarmingly, the same social phenomenon of economic exploitation of black people was still active globally; therefore, black novelists and poets expressed their criticisms and frustrations with white capitalists. Optimistically, they believed properly implemented socialism in their countries would not only bring forth economic justice, but also racial equality. Claude McKay, a Jamaican-born American-based Harlem Renaissance writer, was one of the first African American artists to live in post-October Revolution Moscow and intersect communist ideals with black identity. McKay, likewise to his French-speaking counterparts the region (Haiti, Antilles, French Guiana, etc.), represented a dialectic literary and political reaction to imperialism, Caribbean radicalism. In his autobiography published in 1937, McKay stated in his visit to Russia that: “There is magic in the name of Lenin, as there is splendor in the word Moscow…[and] Lenin himself, whose life was dedicated to creating a glorious new world,” characterized by the spreading of communism.41 In Mckay’s world, black proletarians--like Leninist 20 years--needed to organize, coordinate, and revolt and rise “out of that system” of capitalism. Parallel to Mckay, Négritude writers, especially from Africa, would profess their assent with socialist ideas. Senghor, who would become the first president of Senegal, would intersect Africanite´, or the African-centered identity awareness--inspired by Jean Price Mars’s L’indigenism movement, with socialist perspectives. In speaking about black socialism in the period succeeding the post-Occupation era, Senghor highlights:

The specific objective of African [or Black] socialism, after the Second World War was to fight against foreign capitalism and its slave economy; to do away, not with inequality resulting from the domination of one class by another, but the inequality resulting from the domination of the European conquest, from the domination of one people by another, of one race by another.42

Societal oppression of people of color everywhere, after the major events like WWII and white imperialism, had fundamentally changed the views of Francophone and Anglophone intellectual’s views about socio-political justice for people of African descent. Considering the racial violence which had taken place, race was still front and center; however, socialism seemingly provided a viable political foundation for the black transnationalism, that had been spurred by the historical events such as the U.S. intervention in Haiti.

Haitian Political Discourse in the post-Occupation Era

In Haiti, post-Occupation leaders, intimately understanding the racial misery and degradation of Western imperialism, used citizens’ experiences as political capital for public office. One leader, President Dumarsais Estime, thoughtful of both his own personal limitations because of the intervention and the black/African-memorialized ideologies popularized by the era’s cultural movements, used an anti-Occupation, anti-mulatto platform/philosophy called noirism (“blackism”) to get elected.43 In execution of his rhetoric, Estime--increasingly--institutionalized racial colorism in Haiti, purposely appointing and endorsing, mostly, dark-skinned--rather than light-skinned--citizens for civil servant and cabinet positions. This policy, which was antithetical to all administrations during the Occupation, mobilized anti-American voters in the predominantly dark-skinned, whilst affirming the influence of social ideas from the Harlem Renaissance and Negritude Movement. Both movements centralized the celebration of blackness and African aesthetics, in light of the historical oppression of black people by individuals European ancestry. In Haiti, the lightness of one’s skin was not only a vestige of colonialism, it was a physical reminder of the central socioeconomic schism in the country: elite or poor; French-speaking or Kreyol-speaking; employed or unemployed; voodoo-worshipper or voodoo-denier; Eurocentric aristocrat or African peasant. Blackness, in Estime’s administration, however, reversed these notions; pushing the nation’s cultural identity more towards African roots, using institutional reforms. These political reactions by the people, despite their egalitarian intentions, intensified the nation’s long-established socioeconomic and racial divisions. President Duvalier (also known as “Papa Doc”), Haiti’s 13-year dictator (from 1957-1971), was equally inspired by the Occupation--and prevailing racial notions that came out of this historical event. Duvalier would advantageously promulgate his dark skin tone and Afrocentric ideals, as a method to touch upon the societal resentments of negres, or black Haitian population, during the American Occupation. As Bellegarde-Smith explains:

Although they saw themselves as a vanguard for those behind or below them, Haitian intellectuals were unlikely to emphasize class issues in view of their own status as elites. Transformed into black nationalism/internationalism, political négritude lost some of its “revolutionary” fervor and became increasingly opportunistic. Opportunistic négritude was exemplified later by the right-wing governments of President Francois Duvalier.44

Despite his despotic nature, Duvalier, by virtue of these aforementioned racial characteristics and Négritude-inspired posturing, represented the marginalized black population (90% of the country). He would consistently hold a political base in Haiti. Those who were unduly marginalized and neglected, found hope in individuals like Papa Doc, who as a college-age intellectual studying the black-oriented literature (like Négritude) in the 1920s-30s, understood how powerfully anti-colonial ideas could mobilize “black,” or dark-skinned, Haitians. As Haiti became increasingly authoritarian and alienated by U.S. policymakers, Duvalier strategically re-visited the anti-American/anti-Western notions, which were, in many cases, formed during the historical indignations of Haitians during the American Occupation. This both energized his domestic supporters and seemingly created opportunities to engage like-minded governments, harboring Pan-African, anti-Western, and/or anti-imperialist convictions. Authoritarian leaders, like Duvalier, exploited the psychological traumas of everyday Haitians in their lust for political power.

Conclusion

Was the intercultural connection between Harlem Renaissance and Négritude writers able to survive beyond the U.S. intervention? Overwhelmingly, yes! Writers, poets, and artists from the Harlem Renaissance and the Négritude Movement became political and diplomatic leaders, civil rights activists, and academics, who not only remained in contact, but also reiterated the profound socio-political impacts of the 19-year Occupation in changing the trajectory of intellectual discourse around the world. Both cultural movements fought for a simple yet profoundly progressive principle: people, no matter their skin tone or race, should be treated with empathetic human dignity and equality. The Bantu tribe of South Africa have the term “ubuntu,” which encapsulates the universal bond of humankind and literally translates to “I am because we are '' in English. There are few other terms that truly epitomize the soulful human connection between black intellectuals of the 1920s and 30s, and the spiritual strength of their justice-centered collectivism. Much should be celebrated about the human ability to overcome structural burdens through the principles of universal compassion and conscious interconnectedness.

Bibliography

Anderson, Kevin. “Slavery, War, and Revolution” Jacobin Magazine. Published May 16, 2017. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/05/civil-war-marx-slavery-capital-race-reconstruction.

Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick. Haiti: The Breached Citadel. Revised and Updated Edition ed. Toronto, CA: Canadian Scholars Press, 2004.

Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick and Alex Dupuy and Robert Fatton Jr. and Mary Renda et. al. "Haiti and Its Occupation by the United States in 1915: Antecedents and Outcomes." Journal of Haitian Studies 21, no. 2 (2016): 10-43. https://muse.jhu.edu/ .

Cesaire, Aimé. Cahier D'un Retour Au Pays Natal. Paris, France: Presence Africaine, 1983.

Franklin, John Hope. "The New Negro History." The Journal of Negro History 42, no. 2 (1957): 89-97.

Hastedt, Glenn P. Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. Facts on File Library of American History. New York : Facts On File, c2004., 2004.

Hughes, Langston. I Wonder as I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey. New York: Hill and Wang, 1964.

Hughes, Langston, De Santis Christopher C.. Essays on Art, Race, Politics, and World Affairs. Vol. 9. Columbia, Mo.: Univ. of Missouri Press, 2002.

Ikonne, Chidi. Links and Bridges: A Comparative of the Writings of the New Negro and Negritude Movements. Ibadan, Nigeria: University Press PLC, 2005.

Jean Louis III, Feliz. Harlemites, Haitians and the Black International: 1915-1934. PhD diss., Florida International University, 2014. Miami, FL: FIU Digital Commons. 1-134.

Johnson, James Weldon. Self-Determining Haiti: Four Articles Reprinted from the the Nation Embodying a Report of an Investigation Made for the National Association For Advancement of People of Color. Nation, 1920.

Johnson, James Weldon. The Truth About Haiti: An N.A.A.C.P Investigation. The Crisis, 1920.

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/civil-rights/crisis/0900-crisis-v20n05-w119.pdf

Kuryla, Peter. “Pan Africanism.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Published April 29, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pan-Africanism

Williams, Chad. “African Americans Veterans Hoped Their Service in World War I Would Secure Their Rights at Home. It Didn’t.” Time USA. Published November 12, 2018. https://time.com/5450336/african-american-veterans-wwi/

Lewis, David Levering. W. E. B. Du Bois - Biography of A Race: 1868-1919. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1993.

McKay, Claude. A Long Way From Home. San Diego, CA: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1970.

Munro, Martin. "Can't Stand up for Falling Down: Haiti, Its Revolutions, and Twentieth-Century Négritudes." Research in African Literatures 35, no. 2 (2004): 1-17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3821341.

Pamphile, Léon Dénius. Haitians and African Americans: A Heritage of Tragedy and Hope. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001.

Patti M. Marxsen. ""Masters of the Dew," 1938: A Story by Jacques Roumain." Journal of Haitian Studies 24, no. 1 (2018): 146-155. https://muse.jhu.edu/.

Popeau, Jean Baptiste. Dialogues of Négritude: An Analysis of the Cultural Context of Black Writing. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2003.

Rabaka, Reiland. The Négritude Movement: W.E.B. Du Bois, Leon Damas, Aimé Cesairé, Leopold Senghor, Frantz Fanon, And The Evolution of an Insurgent Idea. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015.

Renda, Mary A. Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of US Imperialism, 1915-1940. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Schmidt, Hans. The United States Occupation of Haiti: 1915-1934. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Pr., 1995.

Senghor, Leopold. "A Prayer for Peace,”(1945). University of Houston, Clear Lake. Accessed April 07, 2019. http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/LITR/5731copo/readings/senghorprayer.htm.

Sommers, Jeffrey William., and Patrick Delices. Race, Reality, and Realpolitik: U.S.-Haiti Relations in the Lead up to the 1915 Occupation. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016.

Endnotes

1. Léon Dénius Pamphile, Haitians and African Americans: A Heritage of Tragedy and Hope (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001), 17.

2. Pamphile, Haitians and African Americans, 16.

3. Pamphile, Haitians and African Americans, 38.

4. Pamphile, Haitians and African Americans, 40.

5. Glenn P Hastedt, Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. (New York : Facts On File, 2004), 204.

6. Jeffrey William Sommers, Race, Reality, and Realpolitik: U.S.-Haiti Relations in the Lead up to the 1915 Occupation. (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016), 10.

7. Sommers, Race, Reality, and Realpolitik, 8.

8. Sommers, Race, Reality, and Realpolitik, 47.

9. Mary A. Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of US Imperialism, 1915-1940. (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2006), 58.

10. Renda, Taking Haiti, 137.

11. James Weldon Johnson, Self-Determining Haiti: Four Articles Reprinted from the the Nation Embodying a Report of an Investigation Made for the National Association For Advancement of People of Color. (Nation, 1920.), 17.

12. Johnson, Self-Determining Haiti, 10.

13. James Weldon Johnson, The Truth About Haiti: An N.A.A.C.P Investigation. (Baltimore: The Crisis, 1920), 224.

14. Peter Kuryla. “Pan Africanism.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, published April 29, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pan-Africanism.

15. David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois - Biography of A Race: 1868-1919. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1993), 414.

16. John Hope Franklin, "The New Negro History." The Journal of Negro History 42, no. 2 (1957): 89-97, 96.

17. Williams, Chad, “African Americans Veterans Hoped Their Service in World War I Would Secure Their Rights at Home. It Didn’t.” Time USA, published November 12, 2018. https://time.com/5450336/african-american-veterans-wwi/

18. Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois, 18.

19. Jean Louis III, Feliz. Harlemites, Haitians and the Black International: 1915-1934. (PhD diss., Florida International University, 2014), 1-134.

20. Jean Baptiste Popeau, Dialogues of Négritude: An Analysis of the Cultural Context of Black Writing. (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2003), 6.

21. Aimé Cesairé, Cahier D'un Retour Au Pays Natal. (Paris, France: Presence Africaine, 1983), 24.

22. Reiland Rabaka, The Négritude Movement: W.E.B. Du Bois, Leon Damas, Aimé Cesairé, Leopold Senghor, Frantz Fanon, And The Evolution of an Insurgent Idea (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015), 28.

23. Popeau, Dialogues of Négritude, 90.

24. Martin Munro, "Can't Stand up for Falling Down: Haiti, Its Revolutions, and Twentieth-Century Négritudes." Research in African Literatures 35, no. 2 92004), 1-17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3821341.

25. Munro, “Can't Stand up for Falling Down,” 5. (the American Occupation really shook up the Haitian psychologically. This deep crisis brought about a moral revolution across all levels of Haitian society, one which gave rise to new centers of resistance)

26. Renda, Taking Haiti, 33.

27. Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1964), 31.

28. Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander, 16.

29. Hans Schmidt, The United States Occupation of Haiti: 1915-1934 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 151.

30. Chidi Ikonne, Links and Bridges: A Comparative of the Writings of the New Negro and Negritude Movements (Ibadan, Nigeria: University Press PLC, 2005), 88.

31. Schmidt, The United States, 55.

32. Langston Hughes and Christopher C. De Santis, Essays on Art, Race, Politics, and World Affairs. Vol. 9 (Columbia, Mo.: Univ. of Missouri Press, 2002), 27.

33. Renda, Taking Haiti, 32.

34. Johnson, Self-Determining Haiti, 13.

35. Senghor, Leopold. "A Prayer for Peace,”(1945). University of Houston, Clear Lake. accessed April 07, 2019. http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/LITR/5731copo/readings/senghorprayer.htm.

36. Sommers, Race, Reality, and Realpolitik, 9.

37. Kevin Anderson, “Slavery, War, and Revolution” Jacobin Magazine, published May 16, 2017. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/05/civil-war-marx-slavery-capital-race-reconstruction.

38. Schmidt, The United States, 151.

39. Patti M. Marxsen, ""Masters of the Dew," 1938: A Story by Jacques Roumain." Journal of Haitian Studies 24, no. 1 (2018): 146-155, 146. https://muse.jhu.edu/.

40. Hughes, Langston, De Santis Christopher C, Essays, 67.

41. Claude McKay, A Long Way From Home (San Diego, CA: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1970), 157.

42. Rabaka, The Negritude, 216.

43. Patrick Bellegarde-Smith and Alex Dupuy and Robert Fatton Jr. and Mary Renda et. al, "Haiti and Its Occupation by the United States in 1915: Antecedents and Outcomes." Journal of Haitian Studies 21, no. 2 (2016): 10-43, 23.

44. Patrick Bellegarde-Smith, Haiti: The Breached Citadel. Revised and Updated Edition ed. (Toronto, CA: Canadian Scholars Press, 2004), 117.