By Heidi Katter, Yale University '20

Edited by Oona Holahan and Louie Lu

Introduction

In July 1889, the United States government sent a commission to northwestern Minnesota to counsel with the Ojibwe of the White Earth and Red Lake Reservations. The object of these visits was straightforward: to negotiate the terms of the newly established Nelson Act, An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota. The ambiguous title fails to convey its insidious intentions. The commission was charged to “negotiate…for the complete cession and relinquishment in writing of all [the Ojibwe’s] title and interest in and to all the reservations…except the White Earth and Red Lake Reservations.” The lands of White Earth and Red Lake would “be allotted…in severalty…in conformity with” the General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act. Any lands remaining after granting Ojibwe individual allotments would “be disposed of by the United States to actual settlers only under the provisions of the homestead law.”1 Even though the Ojibwe at White Earth and Red Lake retained the “privilege” of remaining on their reservations, the Nelson Act powerfully advanced settler colonialism as the federal government infiltrated Ojibwe territory.

The terms of the act met different degrees of success upon the two reservations. The White Earth Ojibwe, after thorough negotiation, complied with the act. In the council minutes documenting the commission’s meetings with members of White Earth, Chief Wob-on-ah-quod proclaimed, “If I was a young man and had the advantages now thrown open to these young men…I should actually overflow with joy.” Another elder, John Johnson, agreed to sign because of the opportunity “to conquer poverty by our exertions” in assuming a sedentary, agricultural existence upon allotted lands. Although some Ojibwe expressed concern that “there would hardly be enough land” for everyone to receive his or her respective allotment, by the end of the meetings, the White Earth Ojibwe agreed to the assimilatory project.2

The Red Lakers, in contrast, remained staunchly opposed to the act throughout their councils with the commission. Statements such as “your mission here is a failure” and “we do not believe it is to our interest to comply with [your] request” frequent the elders’ speech. The Red Lakers not only expressed their resentment of the act, but they also succeeded in resisting some of its terms. Chief May-dway-gon-on-ind dug in his heels, saying “I will never consent to the allotment plan. I wish to lay out a reservation here where we can remain with our bands forever.”3 And indeed, the Red Lake Ojibwe never consented to allotment, nor were they forced to. Red Lakers ceded almost three million acres during the negotiations, but they continued to hold their unceded lands in common—Red Lake remains one of the only reservations nationwide that successfully resisted allotment.4

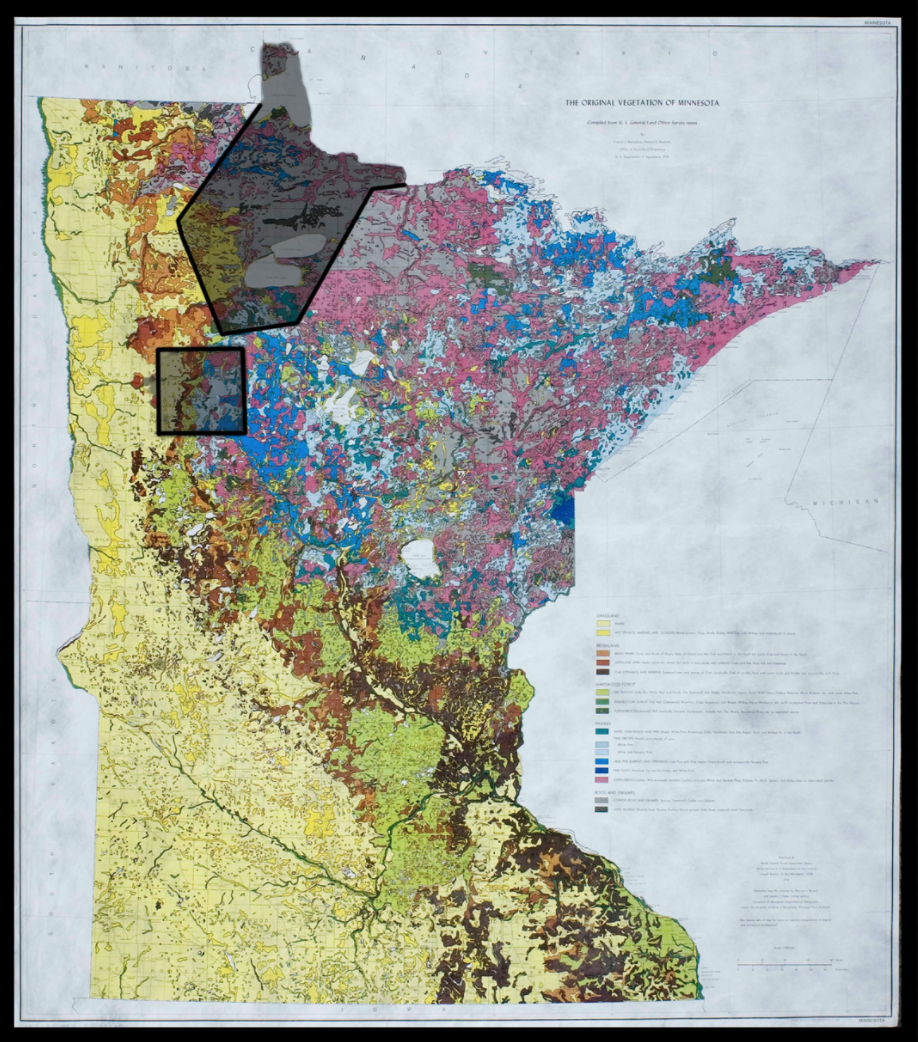

Analyzing maps of Minnesota from this period clarifies the political divergence between White Earth and Red Lake during the Nelson Act negotiations. On the following pages, figures 1–4 show the territorial stakes of this divergence. These figures, depicting General Land Office (GLO) and atlas maps from the mid to late nineteenth century, illuminate how gridded township plats indicating Euro-American legibility—via surveying—unfurl across the White Earth Reservation. The Red Lake Reservation, however, eludes the grid, and the varied visual representations of Red Lake itself reveal the degree to which the United States government remained ignorant of the reservation’s topography and ecosystems. Robert Proctor and Londa Schiebinger coined the term “agnotology” to describe the process of the creation of ignorance. Proctor argues how ignorance “can be a form of resistance to...dangerous knowledge.”5 Drawing upon Proctor’s argument, this paper posits that federal ignorance of Red Lake lands empowered the Ojibwe people to “resist” federal incursion into and settler colonialism of their territory. This essay employs the framework of agnotology to interrogate how and why Red Lake evaded the map compared to White Earth, and to demonstrate how this cartographic invisibility accorded Red Lakers power in their negotiations with the federal government.

The images and captions in this paper narrate the argument as much as the text, so please carefully consider each image and caption while reading. Figures 1–4 comprise a nineteen-year period. The first two figures invite the reader to explore the surveying differences at White Earth and Red Lake between 1866 and 1885. Figure 3, published in 1874, provides a more intimate view of northwestern Minnesota than the first two maps. Figure 4 is a 1878 map that easily locates White Earth and Red Lake for the viewer, serving as a useful reference point for the rest of the essay.

When viewing figures 1–4, it is tempting to explain the differences between White Earth and Red Lake’s legibility in terms of geographic isolation. In the far north of Minnesota, Red Lake lay out of easy grasp of Euro-American settlers, so this seems a reasonable assumption. White Earth was first surveyed in the 1870s; Red Lake not until the 1890s.6 In fact, one of the Nelson Act commissioners told the Red Lakers that “it would be impossible to make the individual allotments” for their reservation in the same manner as for White Earth, as “your reservation has not been surveyed.”7 But the concept of “isolation” itself requires explanation. Isolation is historically produced and malleable, and it has as much to do with the broader logic of settler colonialism as it does with physical distance. How did Red Lake become isolated, while White Earth became legible and appropriable? What factors were involved in producing this isolation?

Reading the GLO and county atlas maps alongside other historical sources exposes the converging factors that resulted in Red Lake’s perceived isolation. The environmental differences between White Earth and Red Lake, the varying political situations of the Ojibwe bands (at the two reservations), and the evolving Euro-American interests in the economic potential of Minnesota’s northern lands all defined the United States’ territorial ignorance of Red Lake in the mid to late nineteenth century. As geographic knowledge enables expropriation, the absence of this knowledge afforded Red Lakers greater autonomy than the White Earth Ojibwe. This historically produced isolation, and ignorance, of Red Lake emerges as the differentiating factor between the White Earth and Red Lake Ojibwe in their meetings with the Nelson Act commissioners.

Scholars have studied the effects of the Nelson Act at White Earth and Red Lake, but none has delivered a large-scale comparison between the two reservations, nor has anyone heavily consulted cartographic sources to inform their research. In The White Earth Tragedy: Ethnicity Dispossession at a Minnesota Anishinaabe Reservation, 1889-1920, Melissa Meyer interrogates the long-term effects of allotment at White Earth. She argues that the opening of reservation lands to Euro-American settlement enabled the rapid dispossession of the Ojibwe, leading over eighty percent of lands to be in the hands of Euro-American homesteaders, speculators, and timber tycoons by 1909.8 Anton Treuer, in Warrior Nation: A History of the Red Lake Ojibwe, frames his narrative of Red Lake around exceptional leaders in the Ojibwe band’s past. While he discusses a variety of factors that defined Red Lake’s historical trajectory, Treuer emphasizes the persevering, “warrior” character of the Red Lake people as setting Red Lake apart from other Ojibwe bands and reservations in Minnesota.9 This paper draws upon these existing narratives while intervening with a cartographic bend to facilitate a comparison between the White Earth and Red Lake Ojibwe Reservations.

The opening section of this essay details the environmental differences between the lands inhabited by the White Earth and Red Lake Ojibwe. The following section highlights how Red Lakers’ ancestral lands were less “isolated” than the White Earth Ojibwe’s in the early nineteenth century owing to the fur trade, and how this changed with the advent of settler colonialism in the American West. The increased “isolation” of Red Lake following the fur trade underscores how historical forces, rather than physical distance, produced Euro-American ignorance of Red Lake lands. The final section employs maps to track how settler colonialism, railroad expansion, environmental conditions, and differing federal legibility of White Earth and Red Lake lands all contributed to the divergence between the Red Lakers’ and White Earth Ojibwe’s responses during the Nelson Act negotiations in 1889.

Forests and Fields

The White Earth and Red Lake Reservations reside in different ecosystems. When Francis Marschner compiled the original survey notes of Minnesota into a vegetation map of the state in the early twentieth century, he crafted a source that illuminated the environmental contexts of White Earth and Red Lake in the era of the Nelson Act . Upon the map in figure 5, White Earth straddles three distinct ecozones—grasslands, deciduous forests, and coniferous forests. When the United States government relocated the Mississippi Band of Chippewa Indians (Ojibwe) to White Earth in 1867, federal agents established a reservation that spanned the three ecosystems to facilitate the Ojibwe’s transition from a hunter-gathering to agricultural lifestyle; in other words, to prepare the Ojibwe to assimilate to a Westernized, settler existence.10 In contrast, the Red Lakers’ ancestral homelands (and eventual reservation) occupied a region rich in coniferous forests, though the western edge of their reservation transitioned to the grasslands that comprise the fertile-soiled Red River Valley. While in the 1880s White Earth consisted of forests and fields, Red Lake was largely forested. Figures 5 and 6 provide visual detail of the ecosystem divisions within each reservation.

Understanding the environmental differences between the two reservations lays the groundwork for evaluating their differing visibility on federal maps. Not only do forests and fields create different experiences in traversing the landscape, but they also hold more or less interest to Euro-Americans depending on contemporary economic incentives. Tracing Ojibwe-Euro-American encounters and their relationships to the land from the fur trade to the reservation era elucidates the role the environment played in Red Lake’s evading the map.

1800s-1850s: The Fur Trade and Exploring the Mississippi “To Its Very Sources”

The map William Clark completed in 1810 (that hangs in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library) shows Red Lake with detailed interest. Lewis and Clark never ventured as far north as Minnesota, but Clark drew on existing geographical sources to fill in information about regions he never visited. While geometrically inaccurate on Clark’s map, the lake is clearly labelled “Red Lake.” When viewing figure 7, notice how a swarm of other words surround the lake: some indicate latitudes, others list “NW Co.,” and others name lakes that form a chain leading southeast from Red Lake. The presence of locations marked as “NW Co.”—representing the North West Company, a fur trade company headquartered in Montreal—reveals the degree to which Euro-American geographic knowledge of Red Lake in the period converged with fur trade interests.11

Euro-American geographic knowledge of Red Lake from the fur trade emerged from navigating the land. Before the fur trade became economically extinct in the 1840s, the northern forests of Minnesota abounded with trading posts where Ojibwe trappers exchanged furs for items such as guns. Relations between early fur traders (especially of French origin) and the Ojibwe resulted in a new ethnic group called the métis, or mixed bloods. The Ojibwe, métis, and European traders coexisted in what Richard White terms the “middle ground.”12 The middle ground describes the process by which Europeans and Ojibwe depended on each other for resources and survival, and the geographic information that adorns European maps from this period grew out of these partnerships.13 The chain of lakes on Clark’s map linking Red Lake to nearby lakes did not develop from a settler colonial desire to survey the land. Rather, fur trade companies created maps to navigate the waterways to manage the outposts that facilitated their economic success. In this way, Red Lake’s visibility on fur trade-era maps did not threaten the Ojibwe’s autonomy. While Red Lake’s forested ecosystems came under European and Euro-American scrutiny for the resources they could provide, the extraction of furs did not coincide with the national project of legibility for land commodification.

In the final years of the fur trade, the Louisiana Purchase redefined the United States’ geographic interest in Minnesota. The parties sent to traverse this northern region were tasked with exploring the “Mississippi river…to its very sources.”14 The first of such explorers, Zebulon Pike, heeded orders from Thomas Jefferson “to make a survey of the river Mississippi to its source” in 1805.15 Similar expeditions soon followed, and maps and travel narratives of the expeditions illuminate the type of geographic knowledge the federal government desired. Figures 8–10 show maps produced by Henry Schoolcraft in the 1830s and Joseph Nicollet in the 1840s that illustrate their attempts at depicting the geometric accuracy of the curvature of the Mississippi and its tributaries. The negative space surrounding the waterways on these maps indicates the degree to which these early expeditions focused more on surveying the immediate waterways and their banks than on the interior lands.

In addition to maps, travel narratives convey the other types of knowledge collected. The War Department “directed [Schoolcraft]” to record “all the statistical facts he [could] procure” about the Indigenous peoples occupying the lands adjacent to the Mississippi River.16 Schoolcraft’s 1830s expedition served as a surveillance mission to record the contemporary Ojibwe occupants of the land. Upon closer inspection, figure 8 lists the precise location of an Ojibwe village near the headwaters of the Mississippi River. The identity of the Ojibwe Schoolcraft encountered in this region sheds light on their future dispossession: they are the Mississippi Band of Chippewa Indians, the band that experienced a forced relocation to the White Earth Reservation in 1867.17 By marking them on his map in his “survey” of national territory, Schoolcraft initiated the project of legibility that would enable their removal.

Schoolcraft not only documented the Ojibwe’s presence, but he also co-opted their geographic knowledge. He hired them as guides, “request[ing] [them] to delineate maps of the country” and asking them “to furnish the requisite number of hunting canoes and guides.”18 By guiding Schoolcraft to Lake Itasca, where he “erect[ed] a flag staff” to claim the land for the United States, the Mississippi Band Ojibwe became unwitting partners in their own dispossession.19 Other contemporary maps, such as those prepared by Nicollet, feature Ojibwe place names alongside English and French names (see figure 9). Although this may signify Nicollet’s respect for the Indigenous inhabitants, the visibility of Ojibwe names nevertheless indicates their complicity in working with the federal government to document the land.

Unlike the Mississippi Band Ojibwe, the Red Lakers lay outside the federal government’s immediate geographic interest. Schoolcraft’s map in his 1834 narrative does not even show Red Lake. And while Nicollet features Red Lake, the detail of the upper Mississippi River region does not carry over to Red Lake or to the waterways surrounding the lake. Nicollet does note the “Indian Village” at Red Lake, but the map gives the impression that the Red Lakers remain isolated. After all, on figure 9 “Chipeway Country” labels Red Lake, while the intricately depicted waterways of the Upper Mississippi region no longer bear such an epithet. A different Schoolcraft map (created with “Lieut. J. Allen” in 1832) recognizes Red Lake’s heritage as a fur trading hub by documenting a chain of lakes reminiscent to what appears on Clark’s map and labeling it “Traders Route to R. Lake” (see figure 10). These depictions highlight the degree to which Red Lake remained in the federal government’s consciousness because of its historical fur trade prowess. Nevertheless, the dawning era of Western settler colonialism led the federal government to favor the Mississippi River regions instead of the forested lands of northern Minnesota.

A travel narrative from 1824 suggests that Red Lake posed challenges for travel that diminished interest in visiting the region and its inhabitants in the early years of surveying. While Major Long, who led the expedition discussed in the narrative, was “proposed to travel along the northern boundary of the United States to Lake Superior,” local settlers informed him “that such an undertaking would be impracticable; the whole country from Red Lake to…Lake Superior, being covered with small lagoons and marshes” that would impede travel by horse.20 Such insight suggests that not geographic isolation, but rather environmental conditions, made Red Lake less enticing for Euro-Americans to visit in the era of surveys. Moreover, William Keating (the author of the 1824 travel narrative) writes that instead of fur trading, the region west of Red Lake must “with a view to the future improvement of the country” focus on producing “agricultural resources.”21 The Euro-Americans’ evolving designs for the land slowly erased Red Lake from cartographic consciousness.

The Mississippi Band and Red Lake Ojibwe experienced differing relations with Euro-American entities in the first half of the nineteenth century. While the Mississippi Band engaged in councils with Euro-American expeditions, Red Lakers sent offerings to these meetings but refrained from visiting. As Schoolcraft recounts, a Red Lake man sent the federal party a peace pipe “as a token of friendship” in “remembrance of the power that permitted traders to come into their country to supply them with goods.”22 As Red Lakers lived out the final years of middle ground trading relations, removed from initial federal surveys, the Mississippi Band Ojibwe unified to assist the federal project of documenting their ancestral lands. The early years of settler colonialism contributed to both Euro-American knowledge of Mississippi Band lands and ignorance of Red Lake territory.

1860s-1889: Railroads Carving a “Route Through Her Own Valleys”

Before railroads wended their way across the Minnesota terrain, a system of oxcart trails traversed the landscape when the earliest Euro-American settlers began to populate Minnesota. Assessing the trails’ routes alongside Marschner’s vegetation map of Minnesota underscores Keating’s conjecture that the future of the country’s “improvement” lay in its “agricultural resources.” While some trails, such as the Woods Trail, briefly cross the Upper Mississippi, most trails hug the western border of Minnesota and entirely bypass Red Lake (see figure 11). The trails, termed the “Red River Trails,” have the Red River Valley as their destination: a region, according to Marschner’s map, of “prairie” and “wet prairie” that lent itself to agricultural pursuits (see figure 6). Oxcarts bounced along these trails, delivering agricultural yields to the burgeoning Minneapolis-St. Paul markets. The object of these trails foreshadowed the function of railroads in succeeding years.

Soon after Minnesota gained statehood in 1858, Governor Alexander Ramsey praised the benefits of railroads in his Inaugural Address. Ramsey declared that “a railroad to the Pacific from some proper point in the Mississippi valley, is already regarded as too important to be longer delayed. It would be most advantageous to…Minnesota…that the question should be determined in favor of the route through her own valleys.”23 Ramsey’s quote anticipates the geographic route the transcontinental line would take to the Pacific Ocean as the young state helped build the national empire from coast to coast.

The oxcart trails also defined the railroads’ routes. While Minnesota contributed to the transcontinental railroad goal, the railroads also functioned locally to deliver prospective homesteaders to farmlands and to shuttle produce to Minneapolis-St. Paul and Eastern markets. In Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West, William Cronon argues that the railroads’ ability to forge “intimate linkages” between city and country allowed Chicago to emerge as an economic power.24 The agricultural produce, such as grain, streaming in from the hinterlands empowered Chicago, and this model can also be applied to Minneapolis and St. Paul in the mid nineteenth century. When the federal government passed the Homestead Act in 1862—granting anyone willing to settle and farm 160-acre plots of land in the West—Minnesota’s population exponentially increased by forty-five percent in three years.25 The converging demographic shifts and railroad expansion in the state determined the rapidity and patterns of settlement.

The process by which the land was surveyed and granted to railroads came to bear on the experiences of the Mississippi Band and Red Lake Ojibwe in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1864, Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act, granting the Northern Pacific Railroad (based in St. Paul) a large tract of public land on which to construct its transcontinental line.26 The act also allowed the railroad company to sell acreage to settlers on either side of its to-be-constructed line as reimbursement for the enterprise.27 The railroad land grant and terms of the Homestead Act required the land to be officially surveyed, and therefore legible, to the federal government. The initial, exploratory surveys that the Mississippi Band Ojibwe participated in decades earlier reached new heights in the 1860s to appease white land hunger and railroad developments.

Turning to figure 1, it is clear that the Mississippi Band’s ancestral lands were fully legible to the federal government by 1866. When read alongside a map of the railroad lines completed in Minnesota by 1870 (figure 12), the surveys appear to facilitate the routes of the railroads. The Ojibwe’s legibility also enabled dispossession, and the Mississippi Band was relocated to the White Earth Reservation (that lay just beyond the farthest extent of the surveys) only a year after this 1866 map was prepared.28 By relocating the Mississippi Band to White Earth, the federal government divorced the Ojibwe from the ancestral lands they willingly shared with explorers decades earlier.

In the milieu of rapid Euro-American settlement and railroad expansion, the federal government resorted to an assimilatory reservation policy in its establishment of White Earth. While granting the White Earth Ojibwe a swath of land encompassing grasslands served to encourage their transition to agriculture, setting aside agricultural lands for the Ojibwe’s benefit also placed the White Earth Ojibwe in the line of fire. By the 1870s, the Northern Pacific Railroad passed less than twenty miles south of White Earth and Euro-American settlements sprang up along the line, leading to white encroachment at the reservation.29 An 1887 map advertising the Northern Pacific Railroad’s lands for sale near the reservation shows White Earth at the top of the map, and the extension of the railroad’s land grant within reservation borders highlights the shaky security the reservation offered its inhabitants in a region under high demand from railroads and settlers (see figures 13 and 13a). A Northern Pacific Railroad guide book, The Great Northwest, even features the White Earth Reservation as a tourist destination. The book urges Euro-Americans to visit “this beautiful reservation, as fair a country as the sun ever shone upon,” stressing that visitors “are always received with kindness.”30 The reservation’s proximity to lands conducive to settler agriculture, in addition to ploys by the railroad to entice Euro-Americans to the lands in and around the reservation, exposes the power Euro-American land interests had in endangering Indigenous land sovereignty.

The extension of the Northern Pacific’s land grant into the reservation encouraged the surveying of reservation lands, which made the White Earth Ojibwe legible twice over: once on their ancestral lands and once again on their reservation. The surveyors first arrived at White Earth in the early 1870s—coinciding with Northern Pacific Railroad developments in the region. By 1877, Indian agent Lewis Stowe wrote to the Surveyor General of Minnesota requesting the “latest map of Minnesota,” as he was “very anxious to procure one with the reservation surveyed thereon.”31 By “procur[ing]” a surveyed map of the reservation, White Earth Indian agents acquired knowledge of what land existed and how it was/could be used (see figure 14). This quantified legibility of White Earth—noting every tree, brook, and clearing upon the reservation—empowered the federal government and enabled the commissioners to coerce the Ojibwe into taking individual land allotments in 1889.

According to the council minutes during the Nelson Act negotiations, though, some of the White Earth Ojibwe not only complied with the act but also endorsed it. Wob-on-ah-quod’s response, that he would “overflow with joy” at the terms, appears too positive considering their history of dispossession.32 Nevertheless, reevaluating mid-nineteenth-century GLO and county atlas maps, and situating these maps in the long history of Ojibwe participation in federal survey processes, gestures to an explanation. As explorers like Schoolcraft exploited Mississippi Band Ojibwe geographic knowledge for federal purposes, Ojibwe sovereignty gradually slipped away until gridded surveys displaced Ojibwe presence on the land. Once within the realm of “known” territory, the White Earth Ojibwe could no longer use territorial ignorance as a form of resistance to federal incursion. For the White Earth Ojibwe, receiving allotments became an opportunity to reinsert themselves into the territorial narrative after relocation, albeit under the terms and using the standards of land commodification. County atlases from the early twentieth century, such as the one shown in figure 15, feature White Earth Ojibwe as owning parcels of land, highlighting the visibility that results from reclaiming land in the form of allotments. Nevertheless, although surveying empowered White Earth Ojibwe to receive individual land allotments, the legibility surveying afforded also paved the way for expropriation—something that White Earth Ojibwe faced in the years following the Nelson Act.

While agricultural and railroad interests defined the White Earth Ojibwe’s experiences leading up to the Nelson Act, environmental circumstances dictated the Red Lakers’ interactions with Euro-American influences. Red Lakers, following the fur trade legacy, remained largely removed from Euro-American entanglements. As most of Red Lake land lay in pine forests, the land did not attract the interests of those traversing the oxcart trails west of the reservation. Returning to the GLO and county atlas maps of the mid nineteenth century reinforces that the federal government remained largely ignorant of Red Lake lands (see figures 1-4).

One particular moment in Red Lake history reveals the degree to which their environmental situation determined their path leading up to the Nelson Act. Red Lakers, unlike the White Earth Ojibwe, always remained on their ancestral lands, but they nevertheless ceded millions of acres through treaties. In 1863, the federal government approached the Red Lake Band and pressured them to cede their lands stretching west of Red Lake into the Red River Valley.33 When reading this treaty alongside Marschner’s vegetation map and the map of the oxcart trails, the agricultural promise of the Red River Valley appears to have determined the federal government’s desire for the lands (see figures 6 and 11). The Red Lakers ceded the lands and in so doing agreed to occupy their remaining homelands in what officially became their reservation.34 Red Lakers experienced dispossession as did the White Earth Ojibwe, but by inhabiting lands less conducive to settler agriculture, they remained out of federal consciousness for a longer duration.

Revisiting figures 1–4 undermines the assumption that Red Lake remained unsurveyed because it was geographically isolated. After Red Lakers ceded lands in the Red River Valley, GLO and atlas maps reveal how quickly the grid extended into the ceded lands. Figures 16 and 17 also show how quickly the railroads followed suit: their focus on tapping into agricultural resources and extending to the Pacific coast made traversing the prairie lands of the Red River Valley more relevant than the pinelands of Red Lake. The Red River Valley resides equally as far away as Red Lake, challenging the use of geographic isolation to explain how Red Lake eluded the grid. If anything, the argument presented in the 1824 travel narrative—that the forested and swampy environment at Red Lake “rendered [the land] impenetrable”—appears a more suitable explanation for why Red Lake evaded surveys until the 1890s.35 Red Lake’s perceived isolation emerges as a historical and environmental, rather than a geographical, construct.

The lack of decent infrastructure—even roads—to Red Lake illuminates the challenges facing the federal government in gaining knowledge of the land. While the government’s disinterest in the land fostered ignorance, the absence of navigable roads reinforced this ignorance. Figure 18 features an 1870s survey conducted at White Earth, which shows a “Red Lake Wagon Road” running through some of the township plats. Red Lake remained so removed from the railroad that the White Earth Agency delivered Red Lake’s mail on a weekly basis. In White Earth’s council minutes in 1889, Kesh-ke-we-gah-bowe complains that the road to Red Lake is “a very bad one,” leading him to repair his wagon weekly to “carry…the mail.”36 That White Earth Ojibwe struggled to reach Red Lake via their road underscores the multiplicity of factors leading to Red Lake’s territorial invisibility.

Federal ignorance of Red Lake lands fueled the Red Lakers’ resistance to the Nelson Act, empowering them to stand by their ancestral and emotional connections to land more than the White Earth Ojibwe. Whereas several of the White Earth Ojibwe greeted the act with enthusiasm, the Red Lakers successfully resisted allotment because their connection to and sovereignty of their ancestral lands had never been shattered. In the council minutes, comments such as “I love my reservation very much” and “we own the land in common whenever we are a community” divulge the Red Lakers’ gratitude and appreciation for their land in its contemporary condition.37 And without survey knowledge of the reservation, the federal commission could only agree that allotting the reservation in the same manner as White Earth would indeed be “impossible.”38 Shaped by environmental conditions, changing Euro-American designs for the land, and political differences at the two reservations, the historically produced isolation of Red Lake emerges as the differentiating factor between the Red Lake and White Earth Ojibwe during the Nelson Act negotiations.

Escaping Notice: The Land as Producing Ignorance

Comparing the White Earth and Red Lake Ojibwe’s ancestral and reservation lands suggests that the land itself also possesses agency over the process of becoming visible. While the upper reaches of the Mississippi River invited early surveyors into the White Earth Ojibwe’s homelands, Red Lake remained largely “impenetrable” except to those adept at navigating “the principal streams in bark canoes.”39

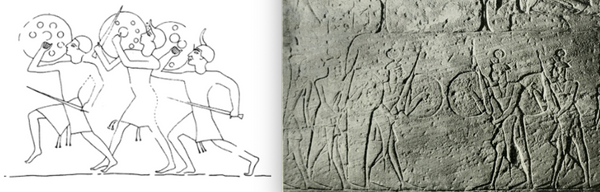

If federal maps reveal Euro-American ignorance of Red Lake lands, then Red Lakers’ experiences highlight the degree to which the land cloaked itself in an aura of mystery—so that even its inhabitants remained ignorant of some goings-on upon the land. When the Ojibwe first settled at Red Lake around 1760, they ousted its contemporary inhabitants, the Dakota, through violent conflict. Yet, unknown to the Ojibwe, a secret village of Dakota continued to dwell at Red Lake for the following sixty years.40 Historian William W. Warren recounts how the Dakota “built a high embankment of earth” and “took every means in their power to escape the notice of the Ojibways.”41 The land facilitated the protection of the Dakota and the ignorance of the Red Lake Ojibwe until 1820, at which time the Ojibwe routed the village.42

In succeeding decades, the transition from fur trading to settler agriculture, the federal survey project, and railroad expansion converged to shift white attention away from the Red Lake region. White Earth instead faced the brunt of Euro-American incursion in the mid nineteenth century, with some Ojibwe viewing allotments as a way of attaining agency in a landscape legible to and commodified by federal powers. While Euro-American interests and Red Lake Ojibwe solidarity contributed to the historical agnotology of Red Lake on the eve of the Nelson Act, the survival of the undetected Dakota village for six decades stresses that the land itself also staked a claim in its persistent evasion of the map.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota. Public Law. U.S. Statutes at Large 24 (1889): 642-646.

An Act granting Lands to aid in the Construction of a Railroad and Telegraph Line from Lake Superior to Puget's Sound, on the Pacific Coast, by the Northern Route. Public Law. U.S. Statutes at Large 13 (1864): 365-372.

An Act to secure Homesteads to actual Settlers on the Public Domain. Public Law. U.S. Statutes at Large 12 (1862): 392-393.

Andreas, A.T. Map of Northern Minnesota, 1874. Map. 1:760,320. Chicago: A.T. Andreas, 1874. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Clark, William. Clark’s Map of 1810. Map. No scale given. 1810. Lewis and Clark Expedition Maps and Receipt. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Description of lands and country along the line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1884. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Great Northern Railway Company. Great Northern Railway line and connections. Map. 1:2,730,000. St. Paul, MN: Great Northern Eisenbahn, 1892. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Keating, William. Narrative of an expedition to the sources of St. Peter’s River, Lake Winnepeek, Lake of the Woods, etc. Volume 2. Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea, 1824. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Marschner, F.J. The Original Vegetation Map of Minnesota. Map. 1:500,000. St. Paul: North Central Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1930.

National Archives at Kansas City, MO. Record Group 75. Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Department of the Interior.

Red Lake Councils, “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” Box 50, White Earth Agency.

White Earth Councils, “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” Box 50, White Earth Agency.

Nicollet, J.N and J.C. Frémont. Map of hydrological basin of the Mississippi River. Map. 1:600,000. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congress, Senate, 1842.

Northern Pacific Railroad Company. Map of the Northern Pacific Railroads and Connections. Map. 1:7,500,000. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally, 1879. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Northern Pacific Railroad Land Department. Map of Becker and Otter Tail Counties, Minnesota. Map. St. Paul: Land Department, Northern Pacific Railroad, 1887. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Page, H.R. & Co. Map of Minnesota. Map. 1:1,260,000. Chicago, IL: H.R. Page & Co., 1885.

Pike, Zebulon. An account of a voyage up the Mississippi River, from St. Louis to its source; made under the orders of the War Department by Lieut. Pike of the United States Army, in the years 1805 and 1806. In The Boston Review 4, Appendix, pp. 25-52. Boston: Munroe and Francis, 1807. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Ramsey, Alexander. Inaugural Address. St. Paul: Minnesotian and Times Printing Company, 1860.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. and J. Allen. Map of the Route passed over by an Expedition into the Indian Country in 1832 to the Source of the Mississippi. Map. No scale given. In Schoolcraft and Allen—expedition to northwest Indians. Washington, D.C.: Gale & Seaton, 1834. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Narrative of an expedition through the upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1834. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. Sketch of the Sources of the Mississippi River. Map. No scale given. In Narrative of an expedition through the upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1834. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Standard Atlas of Becker County, Minnesota. Chicago: A. Ogle & Co., 1911. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

Stowe, Lewis. Letter Book. 1876-1877. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

“Survey Details – BLM GLO Records.” Township 144 N – 41 W. Original Survey (1871). Bureau of Land Management. General Land Office Records. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed November 8, 2019. URL:https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/survey/default.aspx?dm_id=234111&sid=ryx0vnfb.gal #surveyDetailsTabIndex=1.

“Survey Details – BLM GLO Records.” Township 144 N – 39 W. Original Survey (1874). Bureau of Land Management. General Land Office Records. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed November 8, 2019. URL:https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/survey/default.aspx?dm_id=115193&sid=zcvrcb5d.ep5 #surveyDetailsTabIndex=1.

“Survey Details – BLM GLO Records.” Township 154 N – 38 W. Original Survey (1892). Bureau of Land Management. General Land Office Records. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed November 8, 2019. URL:https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/survey/default.aspx?dm_id=49167&sid=a1xfoecp.cvt.

The Great Northwest: A guide-book and itinerary for the use of tourists and travelers over the lines of the Northern Pacific Railroad, its branches and allied lines. St. Paul: W.C. Riley, 1889. Yale Collection of Western Americana. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. New Haven, CT.

“Treaty between the United States of America and the Chippewa Indians of the Mississippi: concluded March 19, 1867; ratification advised, with amendment, April 8, 1867; amendment accepted April 8, 1867; proclaimed April 18, 1867.” Treaties between the US and the Indians, No. 196, Washington, D.C., 1867.

“Treaty between the United States of America and the Red Lake and Pembina bands of Chippewas: concluded March 2, 1863: ratification advised by Senate with amendments March 1, 1864: amendments accepted April 12, 1864: proclaimed May 5, 1864.” Washington, D.C., s.n., 1864.

U.S. Congress. House. Report intended to illustrate a map of the hydrological basin of the upper Mississippi River, made by J.N. Nicollet, while in employ under the Bureau of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. January 11, 1845, 28th Cong., 2nd sess., 1845, S. Vol. 2, serial 464, p. 3.

U.S. General Land Office. Map 8 – Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan. Map. 1:1,267,200. New York: Julius Bien, 1878. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

U.S. General Land Office. Sketch of the Public Surveys in the State of Minnesota. Map. 1:1,140,480. Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Land Office, 1866. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Secondary Sources

Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1991.

Gilman, Rhoda R., Carolyn Gilman and Deborah M. Stultz. Red River Trails: Oxcart Routes Between St. Paul and the Selkirk Settlement, 1820-1870. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1979.

Hoffbeck, Steven R. “Frontier Hotelkeeper: John Wesley Speelman and Buena Vista, Minnesota.” Unpublished manuscript, Minnesota History Center, 1989.

Meyer, Melissa L. The White Earth Tragedy: Ethnicity and Dispossession at a Minnesota Anishinaabe Reservation, 1889-1920. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

Proctor, Robert N. and Londa Schiebinger, eds. Agnotology: The Making & Unmaking of Ignorance. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Prosser, Richard S. Rails to the North Star: A Minnesota Railroad Atlas. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Treuer, Anton. Warrior Nation: A History of the Red Lake Ojibwe. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2015.

Warren, William W. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650- 1815. 20th anniversary ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Wills, Jocelyn. Boosters, Hustlers, and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005.

Endnotes

1. An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota, Public Law, U.S. Statutes at Large 24 (1889): 642-6. “Chippewa” was the term contemporarily used by the federal government to refer to the Ojibwe people. The Ojibwe, all of one Nation, cohered into several distinct groups that inhabited different reservations in Minnesota. Please note that maps discussed throughout the paper are only cited with the figures (not additionally in footnotes).

2. “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” RG 75, Box 50, White Earth Councils, Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, White Earth Agency, National Archives at Kansas City, MO; 80, 83, 33.

3. “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” RG 75, Box 50, Red Lake Councils, Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, White Earth Agency, National Archives at Kansas City, MO; 6, 10, 17.

4. Anton Treuer, Warrior Nation: A History of the Red Lake Ojibwe (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2015), 89, 97. Specifically, Red Lake remains one of two closed reservations in the United States located upon lands that were never ceded to the federal government. See Steven R. Hoffbeck’s “Frontier Hotelkeeper: John Wesley Speelman and Buena Vista, Minnesota,” Unpublished manuscript, Minnesota History Center, 1989, page 57 for more detail.

5. Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger, eds. Agnotology: The Making & Unmaking of Ignorance (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), 1, 2.

6. “Survey Details – BLM GLO Records,” Township 144 N – 41 W, Original Survey (1871), Bureau Land of Management, General Land Office Records, U.S. Department of the Interior, Accessed November 8, 2019, https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/survey/default.aspx?dm_id=234111&sid=ryx0vnfb.gal#surveyDetailsTabIndex=0; “Survey Details – BLM GLO Records,” Township 154 N – 38 W, Original Survey (1892), Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office Records, U.S. Department of the Interior, Accessed November 8, 2019, https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/survey/default.aspx?dm_id=49167&sid=a1xfoecp.cvt.

7. “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” Red Lake Councils, 24.

8. Melissa Meyer, The White Earth Tragedy: Ethnicity Dispossession at a Minnesota Anishinaabe Reservation, 1889-1920 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 142-160.

9. Treuer, Warrior Nation, 15.

10. Meyer, The White Earth Tragedy, 19, 69-72.

11. Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815, 20th anniversary ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 477-79.

12. Ibid., xxv-xxxii; Meyer, The White Earth Tragedy, 28-35.

13. Richard White, The Middle Ground.

14. U.S. Congress, House, Report intended to illustrate a map of the hydrological basin of the upper Mississippi River, made by J.N. Nicollet, while in employ under the Bureau of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, January 11, 1845, 28th Cong., 2nd sess., 1845, S. Vol. 2, serial 464, p. 3.

15. Zebulon Pike, An account of a voyage up the Mississippi River, from St. Louis to its source; made under the orders of the War Department by Lieut. Pike of the United States Army, in the years 1805 and 1806, in The Boston Review, v. 4, appendix, pp. 25-52 (Boston, MA: Munroe and Francis, 1807), 25.

16. Henry R. Schoolcraft, Narrative of an expedition through the upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1834), iii, v.

17. “Treaty between the United States of America and the Chippewa Indians of the Mississippi: concluded March 19, 1867; ratification advised, with amendment, April 8, 1867; amendment accepted April 8, 1867; proclaimed April 18, 1867,” Treaties between the US and the Indians, No. 196, Washington, D.C., 1867.

18. Schoolcraft, Narrative of an expedition, 40.

19. Ibid., 61.

20. William Keating, Narrative of an expedition to the sources of St. Peter’s River, Lake Winnepeek, Lake of the Woods, etc., Volume 2 (Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea, 1824), 58.

21. Ibid., 50.

22. Schoolcraft, Narrative of an expedition, 71.

23. Alexander Ramsey, Inaugural Address (St. Paul: Minnesotian and Times Printing Company, 1860), 22.

24. William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991), xv.

25. An Act to secure Homesteads to actual Settlers on the Public Domain, Public Law, U.S. Statutes at Large 12 (1862): 392-393; Jocelyn Wills, Boosters, Hustlers, and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 108-9.

26. An Act granting Lands to aid in the Construction of a Railroad and Telegraph Line from Lake Superior to Puget's Sound, on the Pacific Coast, by the Northern Route, Public Law, U.S. Statutes at Large 13 (1864): 365-372.

27. Ibid.

28. “Treaty between the United States of America and the Chippewa Indians of the Mississippi: concluded March 19, 1867; ratification advised, with amendment, April 8, 1867; amendment accepted April 8, 1867; proclaimed April 18, 1867,” Treaties between the US and the Indians, No. 196, Washington, D.C., 1867.

29. Description of the lands and country along the line of the Northern Pacific Railroad (Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1884).

30. The Great Northwest: A guide-book and itinerary for the use of tourists and travelers over the lines of the Northern Pacific Railroad, its branches and allied lines (St. Paul: W.C. Riley, 1889), 94-96.

31. Lewis Stowe, Letter Book, 1876-1877, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 96.

32. “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” White Earth Councils, 80.

33. “Treaty between the United States of America and the Red Lake and Pembina bands of Chippewas: concluded March 2, 1863; ratification advised by Senate with amendments March 1, 1864: amendments accepted April 12, 1864: proclaimed May 5, 1864,” Washington, D.C., s.n., 1864. The Red Lake Band was not unified in its decision to accept the treaty. In fact, Ojibwe leaders would walk away from treaties and refuse to participate, should the treaties displease them. This is what happened at the 1863 treaty negotiations. Many Ojibwe simply walked away, but some remained, and the federal government justified their taking of Red Lake lands regardless of if some Red Lakers refused to sign. The Dakota War of 1862 also contributed to the federal pressures to accept the treaty. See Treuer, Warrior Nation, 22-3, 43-67.

34. Ibid.

35. Keating, Narrative of an expedition, 58.

36. “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” White Earth Councils, 88.

37. “Minutes of Councils Called to Accept the Act of 1889,” Red Lake Councils, 39, 15.

38. Ibid., 25.

39. Keating, Narrative of an expedition, 58.

40. Treuer, Warrior Nation, 9, 39-41.

41. William W. Warren, History of the Ojibway People (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885), 356.

42. Treuer, Warrior Nation, 39-41.