Written by Maya Levin, BR' 20

Advised by Professor Paola Bertucci

Edited by Frank Lukens, ES 22',

Katie Painter, TD 23'

Table of Contents

Introduction

Relevant Literature

The British Slave Trade

On Board

In England

Surgeons’ Journals: Primary Source Analysis

Discussion

A Quantitative Lens: On the Journal of Daniel Bushell

Conclusion

Appendices

Appendix One: A Note on Drug Manifests

Appendix Two: Methods of Analysis; A Note on Pharmacopeias; A Note on Prices, Weights, and Measures

Appendix Three: On Note on the Journal of Christopher Bowes

Figures

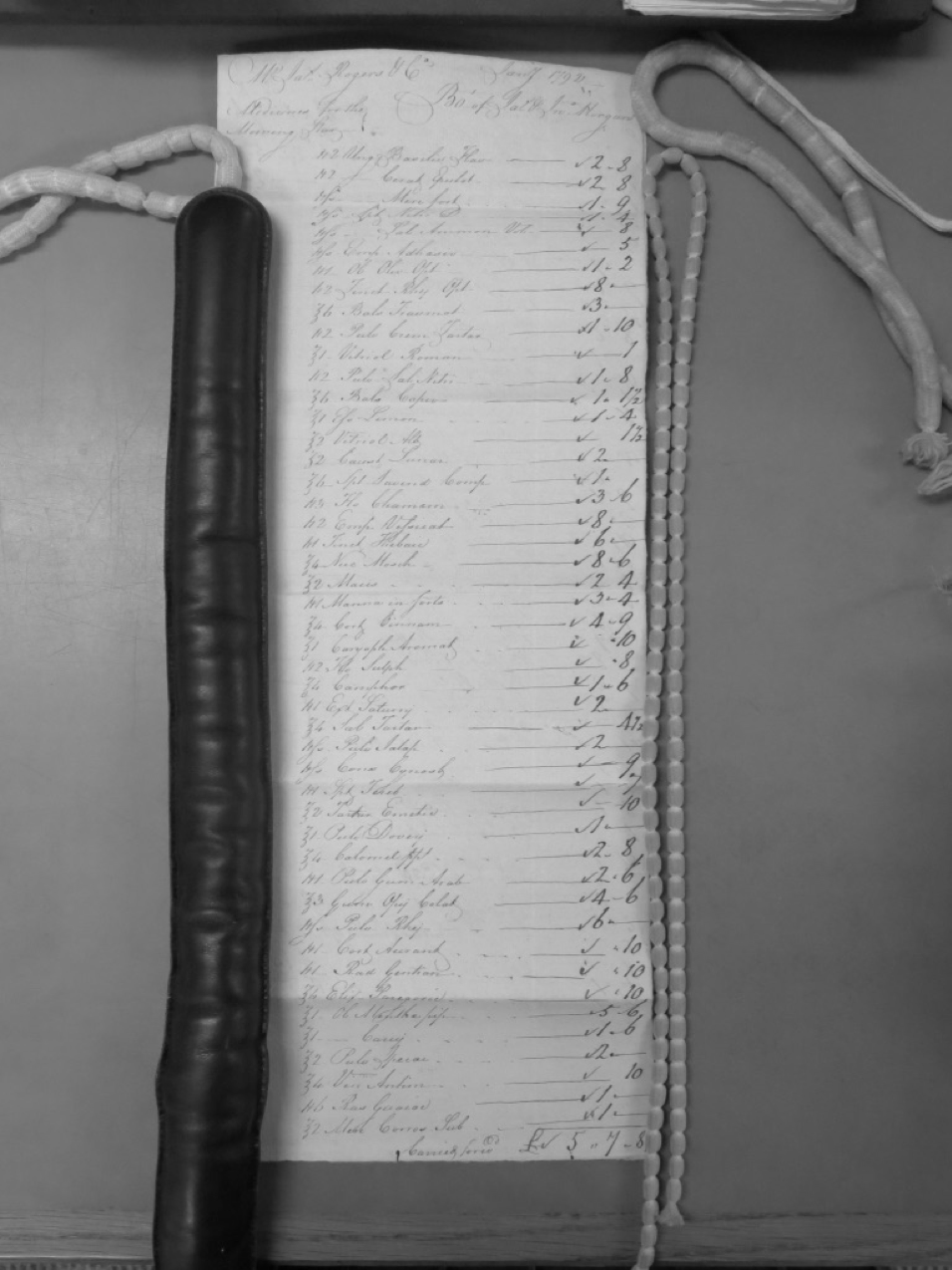

Figure 1: The Journal of James Littlejohn

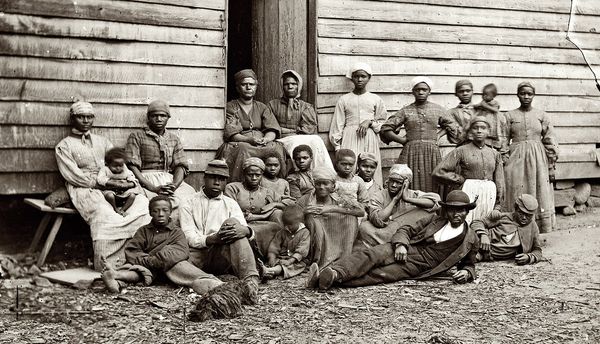

Figure 2: The Journal of Christopher Bowes

Figure 3: The Journal of Daniel Bushell

Figure 4: Tables of Medications from the Journal of Daniel Bushell

Figure 5: Apothecary Weights and Measures

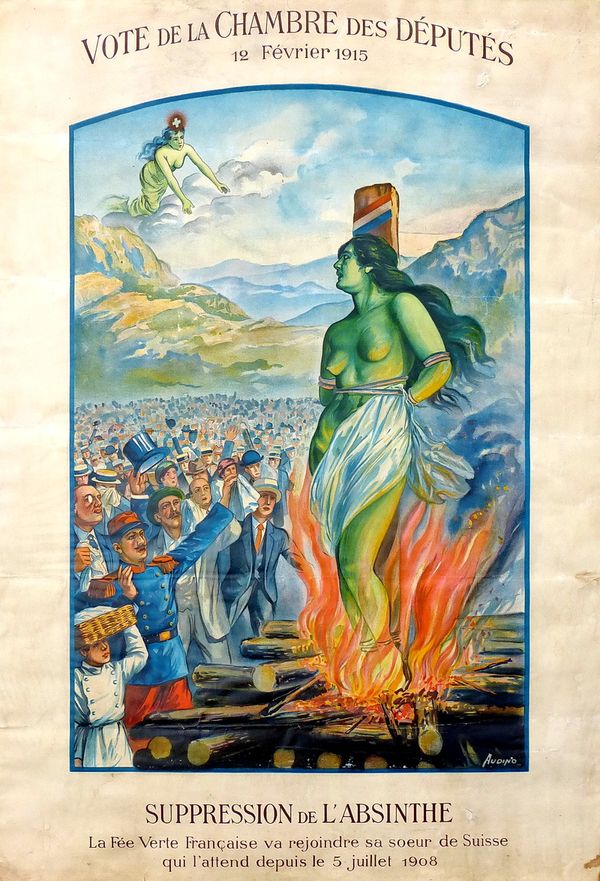

Figure 6: A Slave Ship Drug Manifest

Endnotes

Works Cited

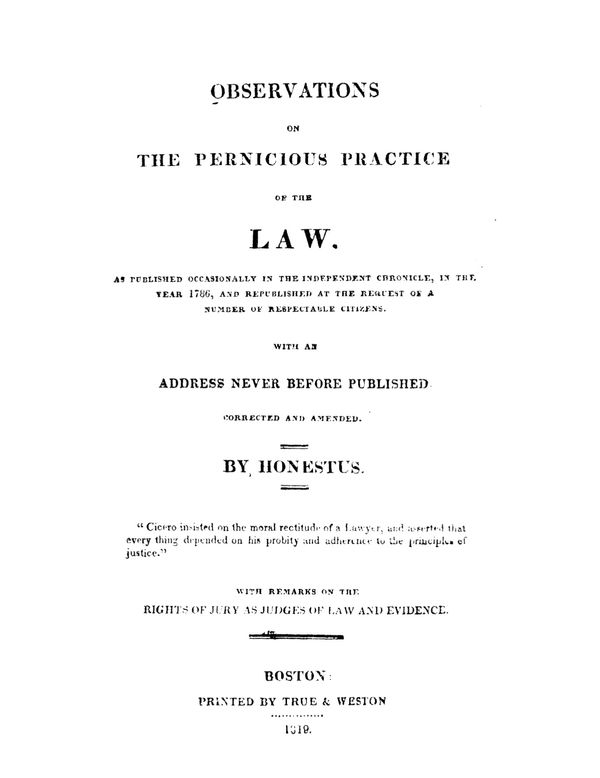

Introduction [1]*

By the time Sir William Dolben recognized the “most crying evil” of the slave trade, almost two and a half million Africans had been forcibly transported across the Atlantic by British slave traders. [2], [3] Dolben, a Member of the British Parliament, was so horrified by his visit to a slave ship at dock in the Thames that he put forward a bill which he hoped would provide for the “relief of those unhappy persons, the natives of Africa, from the hardships to which they were exposed in their passage from the coast of Africa to colonies.”[4] The result of his efforts was the Slave Trade Act of 1788, which put in place a series of regulations regarding the transport of the enslaved and the responsibilities of the slave ship’s surgeon. However, the acquiescence of the bill’s abolitionist authors to the desires of those financially invested in the trade resulted in a barely effective law which failed to impact any of the truly problematic elements of the trade. Nevertheless the Act was supported by the members of the abolitionist movement, who were later joined by those who hoped that ameliorating some of the terrors of the trade would placate the growing movement to abolish it all together. These pro-trade Members of Parliament succeeded in their mission until the British slave trade was finally abolished in 1807, after nearly twenty years of ineffective regulation by Dolben’s Act.

Though there are many lenses through which to analyze the efficacy of Dolben’s Act, the journals that it required slave ship surgeons to keep remain an untapped resource. I examine three such underutilized journals in this essay. By interrogating the language, format, and content of these journals, we gain insight into ways in which slave ship surgeons perceived and treated their patients, both crew members and enslaved Africans. A quantitative analysis of the 1792 journal of slave ship surgeon Daniel Bushell shows an extreme discrepancy in the prices of the medications that he used to treat each of these two groups of patients, even when they were suffering from identical symptoms.

There are a number of possible financial explanations for the different medications Bushell gave to his Black and white patients. Upon examination, however, I suggest that the most plausible explanation concerns the patient’s race. I propose that Bushell’s journal represents an early trans-Atlantic transfer of the scientifically racist medical practices of the colonies, a system which only rose to real popularity in Britain in the mid-nineteenth century. Finally, I argue that my quantitative analysis of Bushell’s prescriptions, in combination with the discursive practices used to document the enslaved in these journals, demonstrates the ways in which Dolben’s Act failed to regulate the constant and active dehumanization of Africans on the Middle Passage.

Relevant Literature

This paper investigates the divergent medical treatment of crew members and enslaved people by ship’s surgeons aboard British slave ships, using journals kept by those surgeons during their voyages. Although scholars have begun to analyze the narratives provided by these primary materials, there is a decided lack of detail in the literature as to the specific remedies used aboard slave ships. Discussions of disease aboard slave ships – when they are even present – are highly focused upon death and the symptoms that preceded it as opposed to treatment of disease; even studies that cite slave ship surgeons’ journals select sections from them that discuss symptoms as opposed to therapeutics. This lacuna in the scholarship has allowed for the loss of valuable information regarding the medicinal practices aboard slave ships, an issue that this paper aims to address.

The body of literature which is most relevant to this analysis can be divided into two broad traditions of historical work. The first, often referred to as “the numbers game,” is a centuries-old practice of statistically examining the slave trade, focusing on mortality rates, rates of disease, ship tonnage, and over-crowding. Although such literature provides valuable quantitative insight into mortality, it does not center the lived experiences of the people involved. As a result, a second approach to slave trade scholarship prioritizes the long-ignored voices and experiences of enslaved people, as well as the daily lives of a slave ship’s crew members, seeking to humanize the history of the slave trade. Both historiographical approaches are valuable and both are essential to this analysis. This paper aims to sit between these two traditions – it is a technical analysis, but one that also seeks to center the less quantifiable insights that we may glean from these primary materials.

The scholarship on mortality rates of enslaved Africans is broad and deep. Scholars such as Herbert Klein and Stanley Engerman examine death rates in their text “Slave Mortality on British Ships 1791 – 1797,” published as a chapter in the book Liverpool, the African Slave Trade, and Abolition: Essays to Illustrate Current Knowledge and Research, edited by P. E. H. Hair and Roger Anstey.[5] The chapter discusses how mortality rates were impacted by various British Parliamentary interventions between 1791 and 1797 that were intended to improve and regulate the living conditions aboard slave ships.[6] Firmly situated within the first, numbers-driven historiography of the slave trade, their essay is a statistical analysis which does not examine the medical treatment of enslaved people or crew members. Peter M. Solar’s text “Ship Crowding and Slave Mortality: Missing Observations or Incorrect Measurement?” provides another example of “the numbers game” in the analysis of death and dying aboard slave ships. He argues that inconsistent and inaccurate measurements of ship tonnage over time resulted in a spuriously broad correlation being drawn between over-crowding and high death rates. This is a correlation which this paper will investigate and which becomes more complex when questions of disease spread and treatment are included.[7]

Scholars who choose to focus on the human experience of the slave trade, which for some is an intervention against this previously popular form of data-driven analysis, give little attention to specific medical interventions in their discussions of disease in the slave trade. In a book of fairly broad scope, Where the Negros are Masters, Randy J. Sparks argues that the Gold Coast port city of Annamaboe is a representative case study, the analysis of which allows for an accurate understanding of the process of enslavement on the West Central African coast.[8] This text uses the stories of individuals to illustrate the entirety of the Gold Coast end of the slave trade, discussing topics ranging from the personal lives of the British governors of Annamaboe Fort to the treatment by the native Fante of their prisoners of war.[9] Sparks’ text offers precise descriptions of the roles and responsibilities of every person involved in the process of preparing an African for life on the Middle Passage and eventual slavery. The functions of the Fante merchant, the European captain, the African canoe-man, and the highly-skilled gold-taker are each examined with great attention.[10] However, in this comprehensive description of the process of enslavement on the Gold Coast, there is only one mention of a slave ship surgeon playing any role in this procedure. Sparks writes that upon boarding, “[c]aptains and ship’s surgeons checked the slaves’ teeth and limbs, and examined their sexual organs for any evidence of venereal disease.”[11] Although the surgeon’s presence is noted, there is no discussion of any treatment that could have been utilized upon the identification of disease in an otherwise desirable slave, or even of the methods of examination that were used in this process.

Similarly, one might expect that an article specifically about a surgeon and his notebook would include documentation of the medical practices used aboard ship. “A Philadelphia Surgeon on a Slaving Voyage to Africa, 1749-1751” by Darold D. Wax, discusses the journal of Dr. William Chancellor during his time as the surgeon aboard the slave ship Wolf from 1749 – 1751.[12] This article aims to provide the reader with an understanding of Dr. Chancellor’s life during the voyage, and does so by first providing a brief overview of his personal history and later quoting the journal he kept during the journey.[13] Though almost half of the article consists of direct quotes from Dr. Chancellor’s journal, there is not a single mention of any actual medicinal remedy. Instead, almost all of the quotations deal with Chancellor’s newfound fascination with the African continent and peoples. Wax in fact straddles the two historiographical traditions we have established, as discussion that does exist of disease and death aboard the Wolf is entirely statistical. Chancellor makes note of the number of slaves remaining alive and the number that died each day, but infrequently includes the cause of death.[14] Even in this text, entirely devoted to the analysis of a slave ship surgeon’s notebook, there is no discussion of specific treatments.

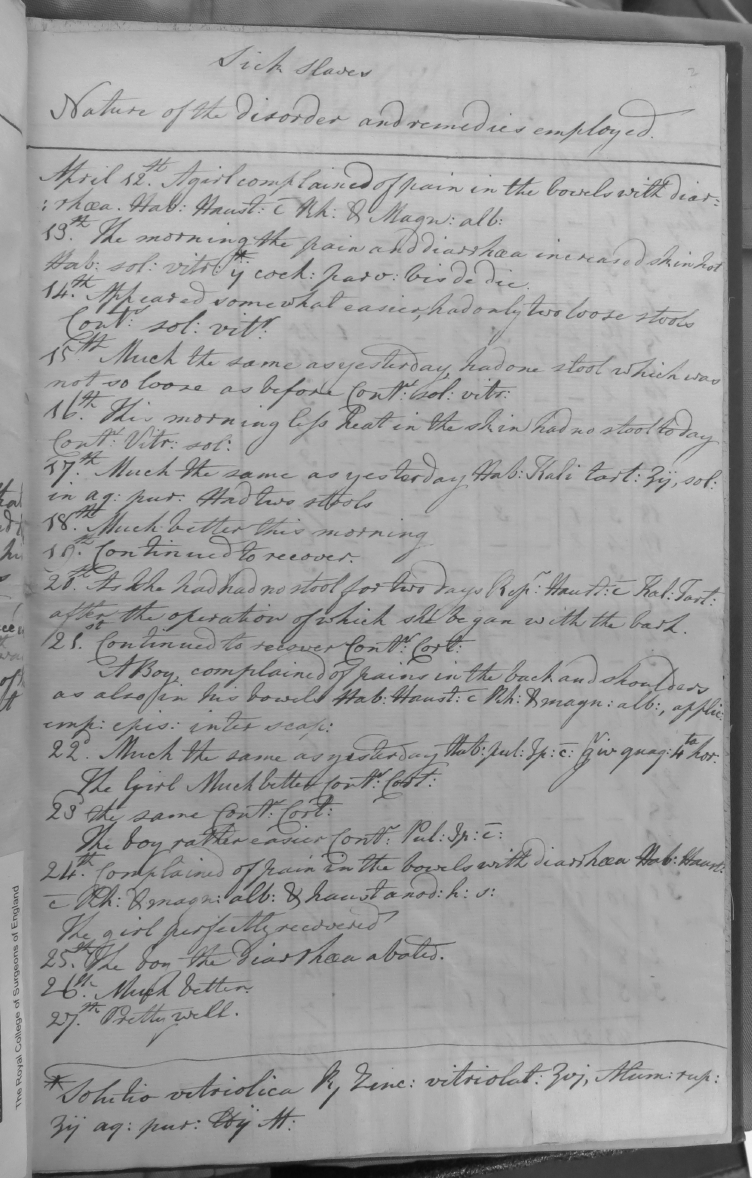

Turning to accounts of the experiences of enslaved Africans themselves, Stephanie Smallwood’s Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora argues that it is entirely necessary to place the human experience of the slave in the forefront of historical conceptualizations of the slave trade.[15] Smallwood’s text provides descriptions of the appalling conditions of life aboard a slave ship, including a fairly detailed discussion of the spread and consequences of disease.[16] Listing common illnesses and discussing individual cases of ships that struggled through each, Smallwood even quotes material of medical importance from one surgeon’s notebook.[17] Although these quotations discuss disease and death among the enslaved, they detail only the symptoms these slaves experienced, not the medications that were used by slave ship surgeons in any attempt to cure them. Sowande’ M. Mustakeem takes a similar approach in Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage.[18] Again focusing on the human experience aboard a slave ship, this text aims to bring the “social space of ships and oceans” into discussions of the slave trade. Mustakeem argues that the impacts of factors such as sexual abuse, trauma, illness, and death must be taken into consideration to correctly interpret the history of the slave trade.[19] Like Smallwood, Mustakeem’s chapter “The Anatomy of Suffering” describes shipboard disease. However, Mustakeem’s argumentation engages more deeply with the primary sources, citing several individual surgeons and discussing the various ailments endured by the enslaved aboard their ships.[20] In fact, one of the surgeon’s journals Mustakeem studies was authored by Christopher Bowes during his 1792 voyage on the Lord Stanley; this same journal is one of the primary sources discussed in this paper. However, again, only symptoms death are discussed; there is no mention of what remedies were used by the surgeons aboard, and the sections of Bowes’ journal which do discuss therapeutic interventions are disregarded.

Finally, it seems that for the most rigorous analysis of slave ship surgeons’ medicinal practices, one must rely on Richard B. Sheridan’s landmark 1981 journal article “The Guinea Surgeons on the Middle Passage: The Provision of Medical Services in the British Slave Trade.”[21] Sheridan uses government documents along with manuscript and print materials to focus on the “the training, recruitment, and practice of the surgeons attached to slave ships.”[22] Sheridan includes descriptions of the biology of the diseases that ran rampant on slave ships, and his essay is the most scientifically-oriented of the texts discussed here.[23] Inspiring the work of later historians like Mustakeem, Sheridan discusses individual surgeons and quotes their journals. However, alone among the texts mentioned here, Sheridan includes a quotation from a slave ship surgeon’s notebook that explicitly includes the medicines that were used to cure a case of diarrhea and fever.[24] He also includes a description of two remedies that were used in the treatment of malaria and ophthalmia respectively, as well as mentioning tarter emetics.[25] However, out of all of the quotations and references in this article, these are the only references to specific remedies, and Sheridan omits the quantities and timing of administration.

Upon review of this subset of the literature on the slave trade and slave trade medicine, it seems clear that there is a lack of attention payed to the actual treatments, medicines, and protocols used by slave trade surgeons on the Middle Passage as documented in their own journals. Though it was required by Dolben’s Act for all surgeons aboard a slave ship to keep a journal during their voyage, relatively few historians of the slave trade have taken on the work of decoding and interpreting these texts, which were often written using Latin pharmaceutical abbreviations.

This lacuna exists despite the salience of such information to both categories of scholarship discussed here. Slave ship surgeons’ journals provide both quantitative information and phenomenally deep insights into the human experience of medicine on a slave ship. In pursuit of a fuller understanding of the medical experiences of both the enslaved and surgeons on the Middle Passage, slave ship surgeons’ journals appear to be a rich but underutilized resource.

The British Slave Trade

Over the course of the Atlantic slave trade, over twelve million enslaved Africans were forcibly transported across the Atlantic by European slave traders. The British dominated the trade during the eighteenth century, and by the trade’s peak in the 1760s, British slave traders were responsible for transporting roughly 42,000 Africans per year. [26] The vast majority were purchased from African traders who brought captives to the West African coast – a grueling, weeks-long journey on foot which is estimated to have taken the lives of almost half of those captured. After being sold to European slave traders, the most terrifying leg of this journey began, as enslaved people were brought on to slave ships to cross the Atlantic ocean. The British slave trade was abolished in 1807, after nearly two centuries of a flourishing trade in human cargo. At the end of it all, it is estimated that the British were responsible for the forced transport of roughly 3 million enslaved Africans, with hundreds of thousands more leaving Africa but perishing at sea.[27]

Two parallel and contemporaneous historical realities existed over the course of the British slave trade. One is the daily experience of slave ship crew members and enslaved Africans in Africa and during the Middle Passage. The other went on in England, and is a story of the changing legal and cultural status of the slave trade in the British Empire. The primary materials discussed in this paper originate in the first of these two historical realities, but the second is absolutely necessary in order to understand the context for, and importance of, these documents and my analysis of them. Here I will explore them separately, but their perpetual entwinement is crucial to keep in mind.

On Board

Though many learn of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade in their early schooling, few people today have a deep understanding of what exactly transpired on eighteenth-century slave ships. The typical British slave ship participating in the triangular trade sailed three major journeys, as shown below. First, a crew of between 20 and 60 men would be hired in a British port city by a captain, funded by the ship’s owners and the merchants financing the voyage. Here, too, a surgeon would be hired if one was not already attached to the voyage in advance. When the crew had boarded and the ship had been loaded with valuables to trade in Africa – primarily manufactured goods such as textiles and arms – the ship would set sail on its journey to the African coast. There, the ship would dock for a period of time typically ranging from several months to a year, trading and purchasing enslaved Africans to sell in the Americas. The famed Middle Passage would then begin, lasting between six weeks and three months, depending on the year of the voyage and the destination. After docking somewhere in the Americas, often the Caribbean, and selling their human cargo, and purchasing other goods, the ship would sail back to the British port of its origin, and the cycle would begin again.

The majority of the literature on the Atlantic slave trade focuses on the second of these three journeys, the Middle Passage, and with good reason. In many ways the Middle Passage defined the brutality and inhumanity of the slave trade. This paper is also centered in the Middle Passage, as the majority of the primary materials examined here were produced during the journey from the African coast to the West Indies. To contextualize their production, and to understand the conditions that Sir William Dolben was seeking to address with his legislation, we must elaborate a little more on this brief overview of the Middle Passage.

The average British slaver held between 200 and 600 enslaved Africans, as well as an average of about 40 crew members. The crew was led by the captain and his first mate, who differed in a number of key ways from the rest of the crew. First, the captain and his mate were usually men of a significantly higher social status than the rest of the crew. This was not a difficult station to achieve, as the majority of the crew members came from extremely humble backgrounds. Because of the infamously terrible conditions aboard a slave ship, those who volunteered were in desperate need of work. It was common for the captain to find too few willing sailors to man the ship. In this case he would often resort to techniques nearing the edge of illegality to recruit his crew: methods which often amounted to something close to kidnap. The captain might hire “crimps,” which were groups of mercenary civilians who served the same role as the naval press, but without the governance of the navy’s regulations and protocols. These men used techniques ranging from plain extortion to enticement with prostitutes and alcohol in order to get potential crew members on board the ship in question.[28] Crew members were paid meager wages relative to their captains and first mates, who were not only paid more in salary but were also paid in “privilege” slaves – a select few slaves that the captain and his mate were allowed to choose for themselves and sell, keeping all of the profits and paying no “freight” or percentage to the merchant.[29], [30]

This system amounted to a hierarchy of abuse. The seamen, often having been forced into working on the slaver, then found themselves living in terrible conditions. Crew members often died from disease. It was commonplace for captains to flog, beat, and in other ways punish their crew.[31] One ship’s surgeon recounted an incident in which his captain tied a member of the crew to the upper part of his ship’s mast for twelve days, giving him only a pint of water per day and a dead bird to eat.[32] Abused, disrespected, and underpaid by their superiors, the crew then turned to the only group to which they were superior: the enslaved. Stories of the physical and sexual abuse by crew members of the enslaved are countless, horrific, and graphic.[33] The rape, beating, and general denial of humanity which the enslaved suffered at the hands of the ship’s crew members would be enough to rid us of any pity we may have felt for those crew members who found themselves on board involuntarily.

The surgeon operated within this hierarchy as well. Though certainly of higher social status than the average seaman, most slave ship surgeons were seeking employment after working for the Royal Navy, and were generally less respected than most other surgeons and doctors in Britain.[34] On board, the surgeon occupied a social status just below that of the captain but roughly on par with his chief mate – in fact, surgeons often went on to captain later voyages aboard other slave ships.[35] Surgeons were paid handsomely, both in a high salary and in the form of “privilege” slaves like those to which the captain and first mate were entitled.

Though often portrayed as independent from the abusive hierarchy on board, the ship’s surgeon was actually an integral part of it. Surgeons participated in the violent treatment of the enslaved in countless ways, but one that was particularly common was the usage of the speculum oris, a metal device which was used to hold open the mouth of an African who refused to eat. The usage of this device was often so violent as to break the teeth of those it was used on. As it was the surgeon’s responsibility to ensure that the enslaved were eating to maintain their health, it was the surgeon who used this device, as well as even more violent techniques, to force fed those who refused food. Thomas Trotter, a surgeon on 1783 voyage of the slave ship The Brookes, testified in the Parliamentary trials on the abolition of the trade that one woman who refused food was “repeatedly flogged, victuals forced into her mouth, but no force could make her swallow [the food] and she lived for the four last days in a state of torpid insensibility.”[36] Trotter speaks here as though he was a witness to this event, when in reality it would have been Trotter himself who carried out this flogging and forced feeding. The violence perpetuated by surgeons and the crew members who assisted them went beyond this forced feeding, though. One man wrote that he had seen:

"…the surgeon’s mates … force the pannikein [of the speculum orum] between their teeth … this was done when the poor wretches have been wallowing or sitting in their blood or excrements, hardly having life; and this with blows with the cat [of nine tails]; damning them for being sulky Black b—: I do declare, that I have known the doctor’s mate report a Slave dead, and have him thrown over-board, when there has been life in him, and he has struggled in the water after being thrown over-board".[37]

Surgeons were active and key participants in the violence against the enslaved, but the traumas they caused were only a small part of the horrific nature of daily life for the enslaved on the Middle Passage. In his famous speech on the floor of the House of Commons, Dolben described the enslaved as “rolling about … in their own sickness and its consequences, fluxes, pestilential distempers, and the danger of premature death.”[38] This assessment of life onboard was not inaccurate in any way. Each enslaved adult would be allowed an area of around 16 inches by 4 to 5 feet below deck in which to spend the vast majority of their time, around 16 hours per day. Lofted, flat wooden structures built around the edge of the room divided the height of the room in half, with Africans lying both under and on top of the structures. This meant that the ceiling would usually be only 4-5 feet above each person, not allowing them to stand up. Though the men and women were divided by sex, the children were allowed to move freely between the two halves of this room. Male Africans were chained together. There was no form of plumbing in these areas of the ship; only buckets, which most of the enslaved could not access, forcing them to relieve themselves where they lay. The vomit, mucus, diarrhea, and blood that resulted from the many illnesses which ran amok in these spaces filled the rooms with an odor so horrible that slave ships were “notorious for reeking so badly that the other ships at sea could smell them before they could see them.”[39] These conditions made transmission of disease extraordinarily easy, with dysentery (both bacillary and emebic), “fevers” such as malaria and yellow fever, and measles, smallpox, and influenza being the most common causes of death on board. As understanding of scurvy, or vitamin C deficiency, grew stronger over the course of the eighteenth century, deaths from this cause decreased, though they were still relatively common.[40] It was common for a number of these diseases to be present on one ship at any given time, as was the case for the True Blue, Daniel Bushell’s ship: his patients suffered from both a respiratory and a gastrointestinal illness. The result of the widespread nature of these diseases was commented upon by Dr. Alexander Falconbridge, a British surgeon who served on board four slave voyages; he later became a fervent and vocal advocate of the abolition of the trade. He wrote that “the deck was covered with blood and mucous, and approached nearer to the resemblance of a slaughter-house than any thing I can compare it to, and the stench and foul air were likewise intolerable.”[41] In the seventeenth century, it was widely expected that 20 percent of slaves would die during the crossing; nearing the end of the eighteenth century that number had dropped slightly as a result of minor regulation of the trade, but remained an astounding 12.5 percent.[42], [43]

For the other hours of the day the enslaved were allowed on the ship’s deck, where they were still separated by sex, with the men being chained together on one side of a tall, spiked wooden wall called the barricado. The women and the vast majority of the crew remained on the other side of this divider, as the crew feared the possibility of a slave revolt. This division also resulted in the widespread sexual assault and rape of the enslaved women and girls by the sailors. It was not uncommon for African women to arrive in the Americas pregnant with the child of their assailant. A wide expanse of netting was secured around the edge of the deck to catch any African who chose drowning, which happened frequently. The enslaved were given small meals of a grain or starch (often rice or corn), commonly with beans, and barely enough water to survive. Every aspect of the daily life of an enslaved African on the Middle Passage would have been filled with desperation and fear. [44]

The scholarship detailing the horrendous conditions of the Middle Passage is deep and thorough. The descriptions found in secondary materials, though – including the one given here – will never match the vividness provided by firsthand accounts. Olaudah Equiano, known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa, described his own experience on the Middle Passage.

"The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship's cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable". [45], [46]

Now equipped with an understanding of the experience of life aboard a slave ship, we now turn to the second of our two, parallel narratives: that of the changing political and social status of the slave trade in England over the course of two and a half centuries.

In England

In 1562, John Hawkins embarked on the first British slave voyage, arriving in 1563 at St. Domingo with slaves for sale. Over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the British began to establish trade routes to the west coast of Africa, purchasing gold, ivory, spices, and dyes in exchange for textiles, rum, and manufactured goods. In 1660, the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa was established and granted a monopoly on British trade with the West African coast. In 1663, the trade in enslaved Africans was added to their charter, and they continued to establish forts and trading posts along the coast. After a brief period of economic depression, the Company was restructured in 1672, at which point it was renamed the Royal African Company (RAC).[47] The RAC dominated the British slave trade until the late seventeenth century, when British colonies in the Americas began to grow, and the demand for agricultural labor increased. Independent British merchants pushed Parliament to open the trade to all and end the RAC’s monopoly. Lobbying of Parliament began in the late 1690s, and by December of 1696 the House heard the first official petition, which drew a direct correlation between the economic success of the colonies and the need for African labor. Parliamentary records read:

"A petition of the Merchants, and others Traders of the city of Bristoll [sic], was presented to the House, and read; setting forth, That the Support of the Plantations in America is of great advantage to the Kingdom, the Product of which is raised by the Strength of Negros; and, according to the greater of lesser Number of Slaves there, the Plantations flourish: and praying, That the House will lay open the Trade to Africa, for Negroes, from Accra to Angola, as the House shall think fit". [48]

Despite the protestation of the RAC, Parliament soon ceded to the pressures of this kind of lobbying, and trade with Africa became legal and open to all British merchants in 1698.[49] Major trade began at many British ports, with the key three being London, Bristol, and Liverpool. These became three of the wealthiest cities in the nation over the course of the trade.

The trade quickly grew from hundreds of enslaved Africans being transported per year to tens of thousands. As the trade expanded and developed into a key component of the British economy, interest in the deeply problematic nature of the trade became a focus of many in Britain. Though the Quaker community had long advocated for the dissolution of the trade and of slavery in the colonies, it was not until the late eighteenth century that a large British abolitionist movement began to receive attention. The first freedom suits in Britain were argued in Scotland: Montgomery v. Sheddan (1755) and Spens v. Dalrymple (1769).[50] However, things only began to shift in 1772, when James Somerset, an enslaved African, and his supporter, renowned abolitionist Granville Sharp, won their case Somerset v. Stewart. This landmark case held that chattel slavery was not legal in England and Wales, though it did not mention the colonies or the slave trade.[51] This case marked the beginning of a golden era for the abolitionist movement – one of countless publications and Parliamentary petitions on the inhumanity of the slave trade.

In 1783, a story swept through Britain which brought to the fore the brutality of the slave trade. Granville Sharp wrote in his journal on March 19, 1783, that “Gustavas Vasa [sic] a Negro called on me with an account of 130 Negros being thrown Alive into the sea from on Board and English Slave Ship.”[52] Gustavas Vassa, today more commonly known as Olaudah Equiano, reported this incident to Sharp; within months, the horrific story of the Zong swept through Britain. The resulting insurance case, Gregson v. Gilbert, was closely followed by many of the key abolitionist figures of the time, and when it was ruled that the killing of the enslaved Africans was legal, it spurred nothing less than fury in many across the nation.

In the aftermath of the Zong case, texts describing the horrors of the slave trade and enslavement became a cornerstone of the growing abolitionist movement. These narratives were written both from the perspective of the British citizen, such as James Ramsey’s 1842 publication “An Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies,” and from the experience of the enslaved person, as in Equiano’s groundbreaking text The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, published in 1789. Countless other famous and deeply impactful abolitionists published their own stories and thoughts: Thomas Clarkson, Josiah Wedgewood, and Alexander Falconbridge, to name a few.[53]

While it was paramount for the Abolitionist movement to change public perception of the slave trade, it was also necessary to alter the legal status of the trade, and, ideally, to abolish it. To this aim, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in 1787. The Society had a broad mandate to educate the masses on the horrors of the slave trade, and the majority of its work was to support and assist abolitionist voices like those mentioned above. However, they also worked directly to petition Parliament, and to educate Members of Parliament on the issue. William Wilberforce, MP, who eventually introduced the first (but unsuccessful) bill in the House of Commons to formally abolish the slave trade, worked directly with the Society.

The Society’s work and publications influenced many other MPs over the course of 1787 and 1788. Most notable was Sir William Dolben, a close ally of Wilberforce, who was MP for both Northamptonshire and the university constituency of Oxford University in his career.[54] Over the course of 1787 he had been in contact with the Society, and his resulting newfound curiosity about the slave trade moved him to bring a group of his fellow MPs to examine a slave ship at harbor on the River Thames in late April of 1788. He was so impacted by the conditions aboard that he later said that they would “shock the humanity and rouse the indignation … of every man of feeling in the country.”[55] This experience led him to fully support serious reform of the trade, which had been in discussion over the course of that parliamentary session. Only days after this visit, on May 9th, 1788, a motion was made to delay discussion of such reforms until the next parliamentary session. Dolben rose to speak against this motion, and delivered one of the most scathing and moving speeches on the slave trade to date. In it, he discussed what he referred to as “a most crying evil,” the Middle Passage.[56] He said that “that intermediate state of tenfold misery which [enslaved Africans] suffered in their transport, from the coast of Africa to the West Indies,” should be regulated as to avoid “putrid disorders and all sorts of dangerous diseases,” which he estimated would kill 10,000 people between the moment of his speech and the next parliamentary session.[57] His reason for action, he said, was nothing more than the “cause of humanity.”[58] He therefore implored the House to regulate the journey on the Middle Passage immediately. William Wilberforce later wrote that Dolben’s speech “produced one universal feeling of pity, shame, and indignation” in those present.[59]

The result of Sir Dolben’s bold stance was the Slave Trade Act of 1788, also known as Dolben’s Act. Though originally written and advocated for by abolitionists, the Act passed with support from many who hoped that this new set of regulations would ameliorate the abuses of the trade without needing to end it. Whatever intentions the authors of the Act may have had, the ways in which the Act regulated the trade were certainly tailored to special interests at the time. We must understand Dolben’s Act, then, both as an humanitarian effort and a sinister attempt to alter just enough as to allow the trade and all of its money-making to continue.

The Act did a number of things to regulate the living conditions of enslaved Africans on board slave ships, with the goal of improving the health and safety of those being transported. Sir Dolben’s intent in the writing of the bill was that it might provide for the “relief of those unhappy persons, the natives of Africa, from the hardships to which they were exposed in their passage from the coast of Africa to colonies,” a goal which the bill sought to achieve in two key ways.[60] The most widely discussed regulation in the Act was to make it illegal to transport more than five men per three tons up to 207 tons, and only one man per ton after that.[61], [62] Prior to the Act, it was conventional to carry at least six men per three tons, which amounted to a space of 5 ½ feet by 16 inches per adult African, to which they were confined up to 16 hours per day.[63] The Act expanded this space by 20 percent, a change which, however small it may seem, significantly limited the number of Africans transported per ship.

This portion of the Act was responsible for the majority of the bill’s damaging financial consequences for slave merchants, and therefore became the most famous and discussed aspect of the legislation. However, it is also clear that the Act did not change the amount of space significantly enough to make for anything like a humane living situation: this was almost certainly as a result of push back from Members of Parliament who were deeply invested in profiting from the trade. James LoGerfo writes that many involved in writing the Act argued that “the remedy [for the evils of the trade] should be temperate and take account of what was attainable as well as what was desirable…” The Act therefore also stated that any further regulation of the trade – aside from the exact “mode of conveyance” of cargo – would be left to the provincial legislatures instead of being done in Parliament. LoGerfo argues that “this was an attempt to mollify the wrath of the merchants since they had claimed there was no need for additional legislation in view of the plethora of such passed by provincial legislatures.”[64]

The Act contained another set of regulations which appear to align with the goals of the authors, but may have in fact been tailored to please a particular lobby. This portion of the bill dealt with the presence and responsibilities of a ship’s surgeon on board each slaving voyage. The Act required that a surgeon with evidence of “having passed his Examinations at Surgeon’s Hall, or at some Public or Country Hospital” be on board for each voyage. This is interesting because “guinea surgeons,” so called for the African ports at which they landed, are recorded as serving on slave ships as early as the 1550s – there was no need to mandate their presence, as surgeons were almost always on board a slave ship anyway.[65] However, the bill now required that surgeons be certified by an official institution – a lucrative business which burnished the reputation of a hospital or Surgeons’ Hall.[66] In the original bill, all surgeons were required to be certified at Surgeon’s Hall in London. This monopoly angered the Surgeons of Edinburgh, though, who did not want to lose out on these new financial benefits. They appealed to their MP, Henry Dundas, and Dundas pushed through an amendment that allowed slave trade surgeons to be certified at any Surgeon’s Hall and some private hospitals.[67], [68]

A number of deals were clearly struck in the passage of this bill, and it is certainly arguable that those sacrifices were made to the detriment of the original goal of the legislation itself, prioritizing the financial benefit of those involved over the actual achievement of the author’s intent. Neither of these requirements did anything to solve the real issues with the trade: the constant dehumanization of and violence against the enslaved.

A second kind of regulation the Act put in place was a bonus system for the captain and surgeon if the mortality rate of the voyage remained low. If the death rate remained below two percent of the largest number of slaves on board, the captain would receive a £100 bonus, while the surgeon would be given a £50 bonus: an amount that could have been equal to as much as a quarter of their overall earnings from the voyage.[69] There was a similar system with smaller rewards if the mortality rate was below three percent.[70] Although this may seem like an effective incentive system for the surgeon to care about the wellbeing of his charges, we will see later why this may have been far less motivating than we might expect.

Lastly, and most importantly for this paper, the bill also included a provision that had the potential to truly hold the ship’s surgeon liable for his actions. After the events of the Zong, in which there were no records of the deaths of the enslaved Africans (or of anything, for that matter, as the ship’s log book had disappeared while at port in Jamaica) the Act established a robust legislative structure for the keeping and handling of a surgeon’s journal. This diary was meant to document the medical events that occurred during the journey – a system to ensure that there was a good reason for each and every death on board. The Act required that the surgeon keep a “Regular and true Journal,” and said that the surgeon should

"…deliver such Journal to the Collector … at the first British Port where such Ship or Vessel shall arrive after leaving the Coast of Africa, and shall make Oath to the Truth of such Journal, to the best of his Knowledge and Belief, before such Collector or other Officer as aforesaid, … [and] Copies shall severally be attested (as true Copies) by such Collector … and Duplicates of the said Copies… shall be transmitted by the said Collector or other Chief Officer to the Commissioners of his Majesty’s Customs in London". [71]

This regulation was designed to ensure accountability. Its goal was to create a system according to which the British crew of a slave ship might answer to something more concrete than their own whim. The fact that Sir Dolben believed that a surgeon’s journal was capable of creating this accountability is notable. It implied that the surgeon was a trustworthy source as to the daily events on board. But more importantly: by selecting regulation of the surgeon as his tool to provide “relief for those unhappy persons,” Sir Dolben was, in a way, entrusting the surgeon with the humanizing intent of this legislation. By making the ship’s surgeon the man of record, and by selecting the surgeon as the point of regulation, Dolben implied that the surgeon might be the person most able to impose a set of moral standards on the treatment of enslaved people. This suggestion stands in stark contrast to the testimonies, cited above, of the active participation of the ship’s surgeon in precisely the behavior the enslaved needed relief from.

It is no mystery what conditions made Sir William Dolben so sure of his desire to regulate the slave trade after that April visit to a ship on the Thames. His chief aim, then, was a moral one: to lessen the horror of the lives of enslaved African on the Middle Passage, and possibly even to find ways to diminish the dehumanization of the enslaved. He chose two key ways to do this: expand the space given to each adult African, and regulate the surgeon and his journal. Did Sir Dolben choose his points of regulation wisely? Was he correct in believing that a ship’s surgeon would be a person willing and able to commit to the moral goals of this legislation, to treat enslaved people as human beings worthy of “relief”? Even if this legislation might have been effective originally, did the ways in which the authors acquiesced to the special interests of Parliament mitigate the real goals of the bill? And, most importantly, even if the surgeon could bring this goal to fruition, did he? This is the central question which my primary analysis seeks to answer.

Surgeons’ Journals: Primary Source Analysis

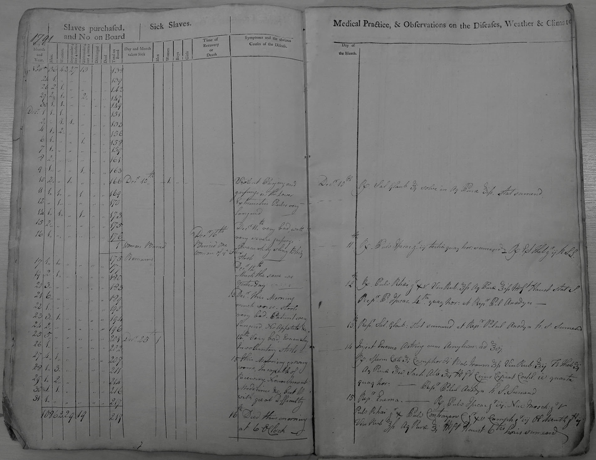

Dolben’s Act made it mandatory for a surgeon to be on board every British slaving voyage and for that surgeon to keep a “regular and true journal” of the medical goings-on of the journey. As was noted above, surgeons were often present long prior to 1788, and they would have kept journals. However, the Act marks 1788 as a moment of transition in the formatting and content of these surgeons’ journals. The journal of James Littlejohn, the surgeon of the slave ship the True Blue, was written during the ship’s journey from Liverpool to Benin from April to June of 1770 (Figure 1). This text acts as a window into the way that a journal like this may have been kept prior to 1788. It is written on blank pages, freely scrawled without particular organization of content, with the day given at the beginning of each paragraph – many days have no entry at all.

After 1788, surgeons’ journals became significantly more organized, regularly maintained, and uniform in structure. These journals all conformed to the specific requirements of the Act, which mandated that the surgeon’s journal contain “an Account of greatest Number of Slaves which shall have been at any Time during Such Voyage on Board such Ship or Vessel, … distinguishing the Number of Males and Females, and of the Deaths of any such Slaves, or Crew of the said Ship or Vessel, and of the Cause therefore.”[72]

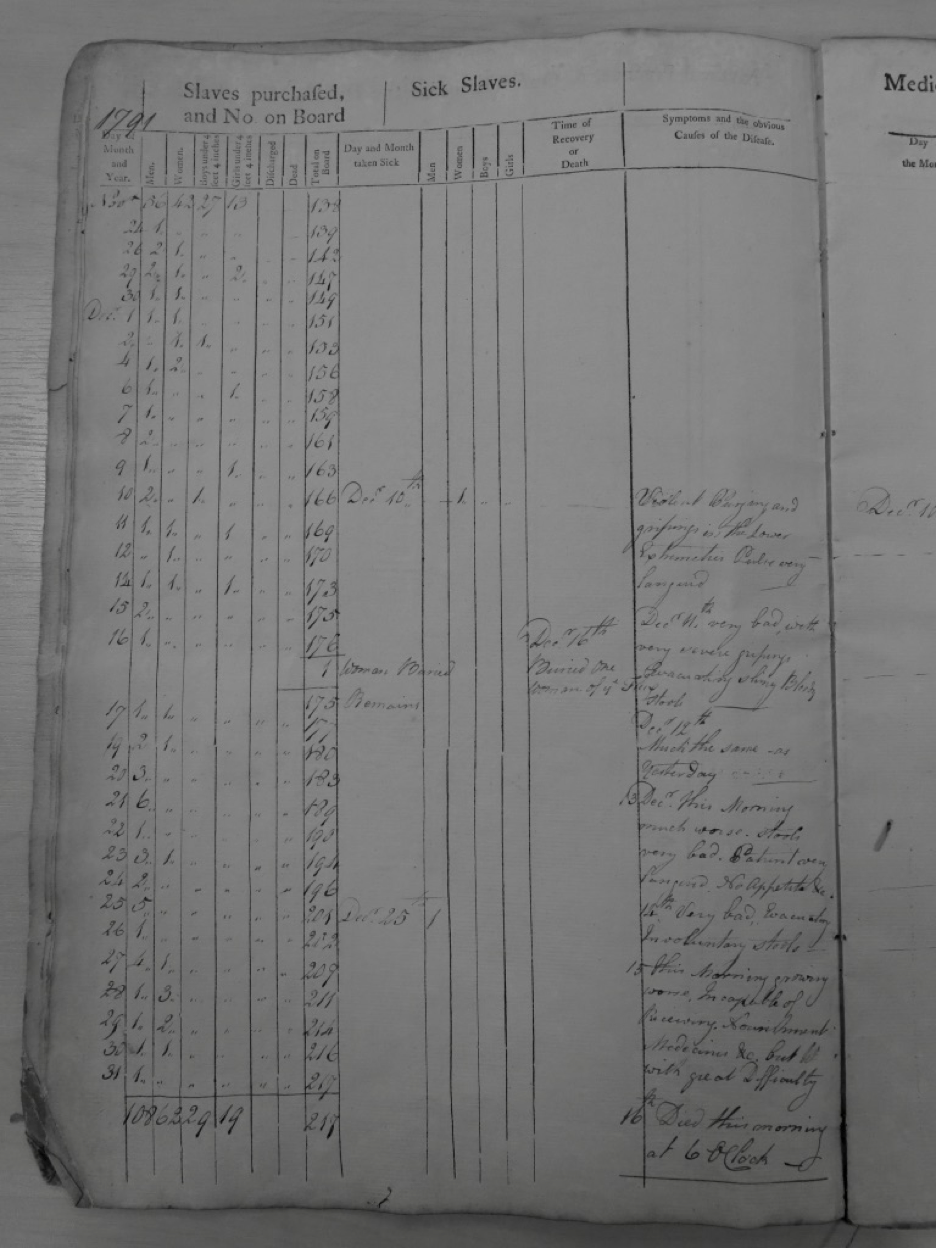

Figure 1: The journal of James Littlejohn, 1770.

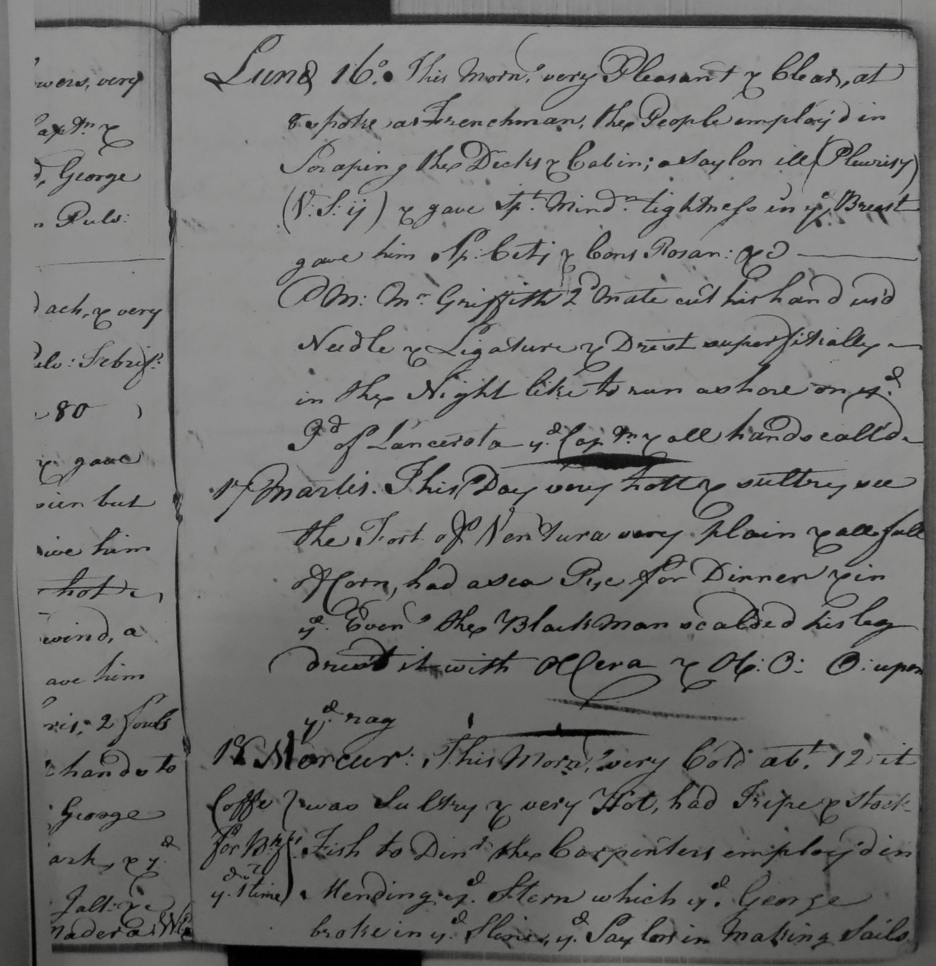

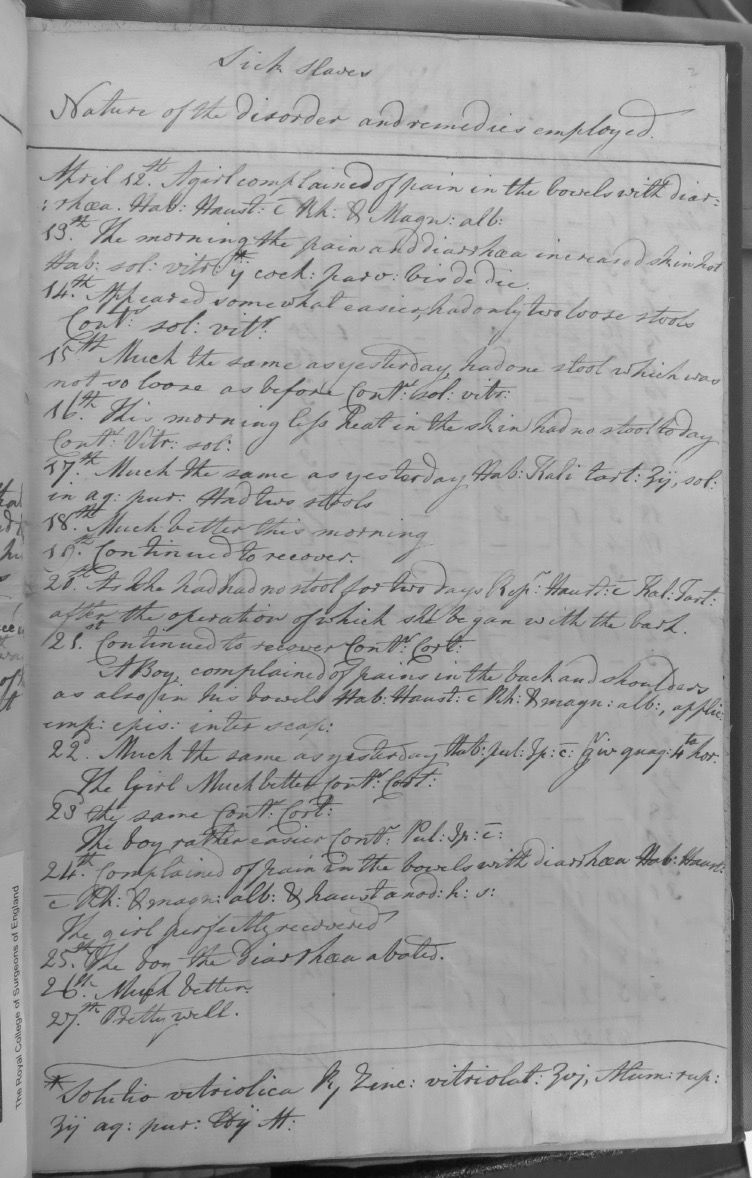

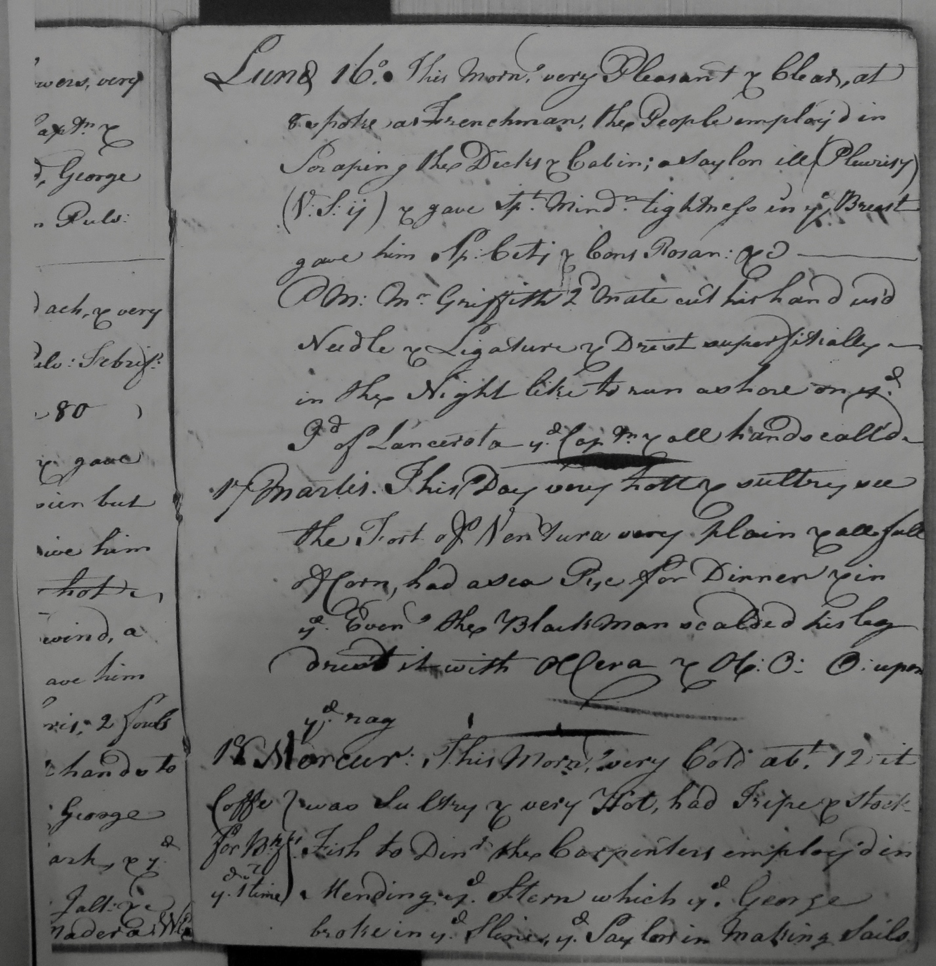

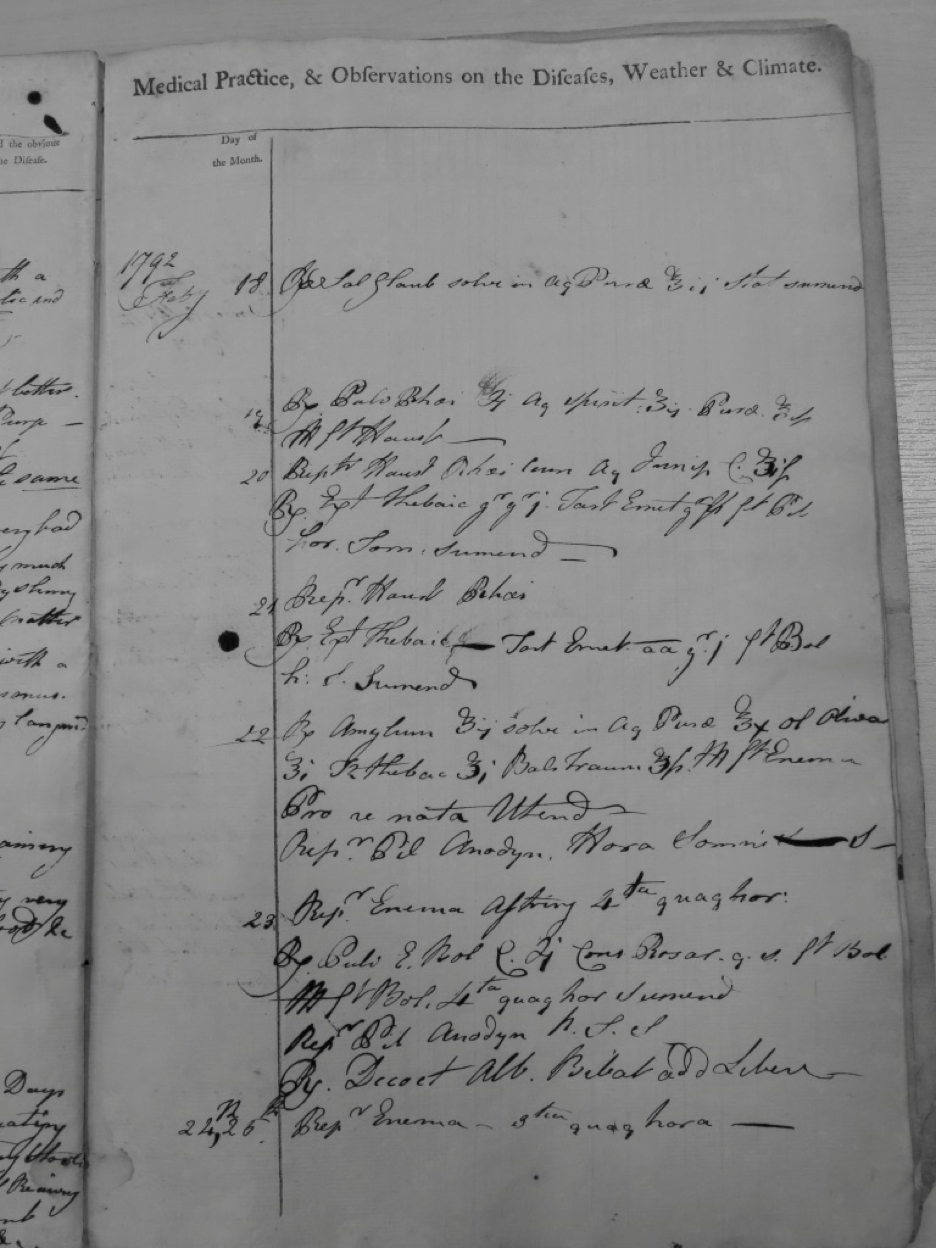

One such journal is that kept by Christopher Bowes during his time as the surgeon aboard the slave ship Lord Stanley, which departed from Liverpool in December of 1791 and landed in Grenada in October of 1792 (Figure 2).[73]Bowes’ diary can be taken as a typical example of a post-1788 journal. The book itself is handwritten and worn. On the left hand side of each spread of pages is a table, which lists, for any given day of the voyage, the number of slaves in each of the following categories: “Men, Men Boys, Boys, Women, Women Girls, Girls, Discharged, Dead, Total Purchased, Total on Board.”[74] Beginning on March 23, 1792, the tabulation continues until July 26, 1792, at which point it is replaced by longer, handwritten summaries for the remainder of the voyage. On the right hand page is a narrative of the illnesses of individual slaves, listing their symptoms and medications given each day until their recovery or death, which is titled “Sick slaves / Nature of the Disorder and remedies employed.”[75]

Figure 2: The Journal of Christopher Bowes

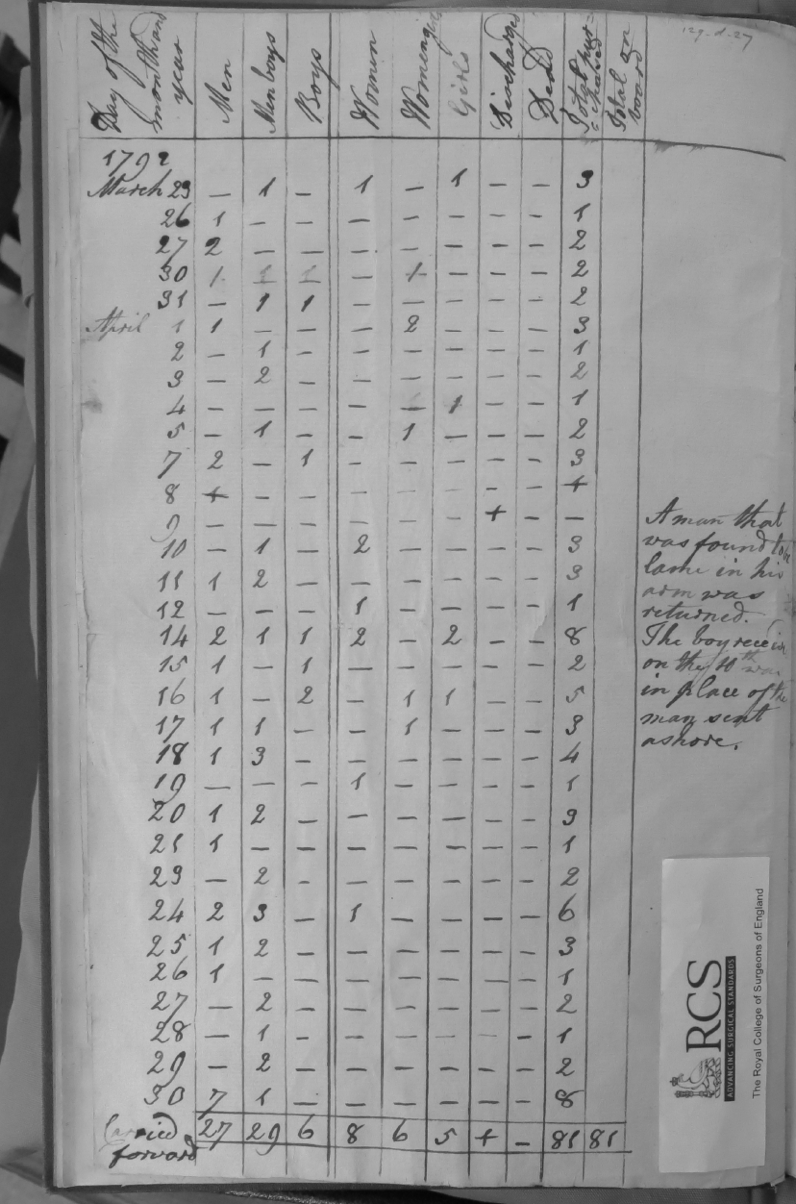

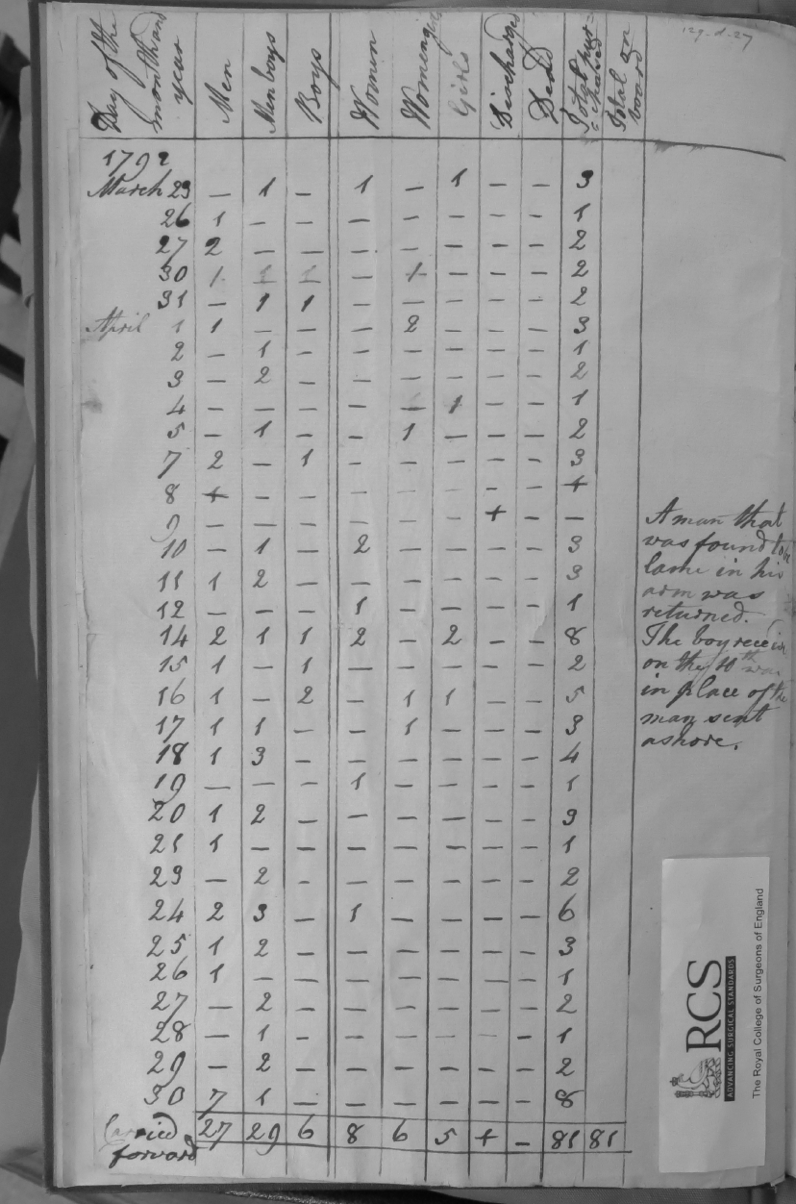

This format of side-by-side tables and narratives was a common way to ensure adherence to the requirements in Dolben’s Act, and can also be seen in the journal kept by Daniel Bushell. Bushell served as the surgeon aboard the Alice on its voyage from Liverpool to the island of St. Vincent from 1791-1792 (Figure 3).[76] His journal includes a printed table nearly identical to the one hand-written in Bowes’ journal. The sections of his journal are “Slaves Purchased and [Number] on Board / Sick Slaves,” and “Sick Journal of Ship’s Crew,” each with accompanying pages entitled “Medical Practice, Observations on the Diseases, Weather and Climate.”[77]

Figure 3: The journal of Daniel Bushell, 1791-1792.

Each of these journals fits differently into the history of Dolben’s Act. Littlejohn’s was before the law was written, and exemplifies the unregulated version of slave ship documentation that existed prior to the changes made by the Act. Because Littlejohn passed away shortly after the True Blue’s arrival at port in Benin, his journal includes very little mention of medications given to enslaved Africans. However, it gives a detailed account of medications and interventions used on crew members, and exemplifies the language that at least one of these surgeons used to describe sick and injured crew members. On the other hand, both Bowes and Bushell sailed after the Act, and their journals both clearly demonstrate the impact of the structural regulations of the legislation. Bowes’ text also embodies a different portion of the Act’s regulations: it is a copy of the original journal, which was likely made as a result of the Act’s requirements that copies be produced and sworn to be faithful replicas. [78] Bowes writes primarily of medications given to enslaved Africans, not crew members.

The majority of Bowes’ and Littlejohn’s journals each center on one group of people: the enslaved and crew members, respectively. This difference renders these two journals extremely helpful in gaining an understanding of the human meaning behind these texts. The strategies of dehumanization used in each of the texts are clear, both independently and when compared to one another. In contrast with both Bowes and Littlejohn, Bushell’s journal serves as a unique example of a journal which documents medications given to both enslaved Africans and crew members – by the same surgeon, on the same voyage. I center my quantitative analysis in Bushell’s journal, as this juxtaposition allows for an analysis of the diverging medical treatment given to these two groups of people. The data derived from this journal creates one more lens through which we can interrogate this history. How do these journals help us understand the efficacy of Dolben’s regulations? Is there a difference in the abusive behavior of surgeons as it is recorded by Littlejohn, written before the Act, and the other two journals, written after? In other words, do the journals provide evidence that the regulations in the Act stopped any of the violence and dehumanization that was rampant before it? Stepping back, what can we really learn from a quantitative, “numbers game” kind of history like this, and what does a statistical lens obscure?

Discussion

These journals provide deep insight into the medical practices on board a slave ship and into eighteenth-century British surgery, more broadly. However, the language used by their authors, the kinds of content they record, and the organizational system they used to record it, shed light on a much bigger historical problem: the dehumanization of Africans in the slave trade. We have discussed the ways that Africans were treated as objects, not humans: the living conditions on board, the process of their capture and sale, the very fact that they were sold at all. But there was a far more tangible, active process of dehumanization that occurred over the course of a voyage; it was not just a passive consequence of the treatment of people as animals. This was a process that the crew, the captain, and the surgeon all participated in. Even the surgeon’s notebook was implicated. The tradition of dehumanization ran deep in the practice of the trade, even after Dolben’s weak attempt to fix it, and these journals are evidence of it.

As Emma Christopher writes in her chapter “Sea Changes,” it is absolutely imperative that the historian of this period have a deep “understanding the role of seamen in the [M]iddle [P]assage, because conversion of African captive into slave required more than simply time spent below decks and transfer across the Atlantic: it also involved the preparation of a sovereign people for sale at market as chattels … [this process] formed part of the larger panorama that attempted to alter human being to thing.” [79] Being the “enslaved” was an imposed identity, one that was forced upon Africans who had never before been anything besides autonomous people, humans in their own skin. At that point a process of dehumanization began, stripping enslaved Africans of their external identity as human beings. This was a process intended to reduce them to something much smaller and weaker, partially in response to the terror the crew felt of slave uprisings and revolts. Many stories make it clear that this process did not succeed in destorying the inherent autonomy and “irrepressible humanity” of the enslaved. [80] But the many more that highlight the treatment they received – treatment far worse than that of livestock – remind us of the profoundly abusive reality of the slave ship.

This process began long before any individual person was traded on the African coast and brought on board a ship. Before the ship set sail for an African port, the owner of the ship would enter an insurance contract with an insurance broker and a set of underwriters: a contract that insured the cargo of their ship on all three legs of the triangular trade.[81]This meant that the enslaved Africans whom they carried across the Atlantic were insured – a fact which, under British law at the time, implied a lack of humanity in and of itself. Though specific kinds of life insurance were legal in Britain, maritime life insurance was generally reserved for the particular circumstance of pirates taking over a ship and holding the crew in captivity. This insurance would cover the ransom of a captured sailor or passenger. In the rest of Europe – which was predominantly Catholic at the time – it was forbidden to insure a human life, as it was considered blasphemy: “death is God’s prerogative.”[82] Aside from those in need of ransom, the enslaved were the only exception.

There are two different lines of legal reasoning for this exception, and scholars disagree as to which was more widely agreed upon at the time. Some argue that insurance for enslaved cargo escaped this prohibition because slaves were, legally, not people: they could be insured as “walking cargo.” Tim Armstrong argues that this is a “retrospective construction” of the legal system at the time, one built around our modern understanding of the dehumanization of the enslaved. Others argue that it was by considering the enslaved as being captured and held in ransom that European slavers were legally allowed to insure their slaves. Armstrong quotes from Geoffrey Clark, who writes that “because a ransom could be seen as a price on freedom, the law could treat insurance against captivity as something different in kind from the money valuation of human life itself…”[83] This convoluted reasoning allowed the Catholic French to begin insuring their slaves when it may otherwise have been forbidden.[84]

The first of these two arguments is more commonly referenced, and it is the first that was clearly held in the most famous insurance case from this period, Gregson v. Gilbert, the case of the Zong. Though the precise legality of this case came down to the various kinds of risks and the insurance construct of “sacrifice,” the finding in the initial case was clear: when faced with the “Perils of the Sea,” the captain had the ability to sacrifice part of his cargo to save the rest, and this was covered by his insurance. This verdict resulted in the payment of the ship’s owner by his insurer for the Africans whom his captain had purposefully killed, because, as Lord Mansfield wrote, “the case of slaves was the same as if horses had been thrown over board.”[85] It is clear, then, that Africans were not insured as people, but as livestock, as (human) cargo. A secondary financial system which reinforced the dehumanization of the enslaved was the very idea of a privilege slave. The payment of a captain or surgeon in the form of a privilege slave was rooted in the conception that Africans were worth precisely their sale price, and solidified their only value as a method of transferring money.[86]

This legally dehumanizing insurance deal and payment structure were in place long before any African set foot on board a slave ship, and was not even mentioned in Dolben’s Act. The active denial of the humanity of the enslaved continued onto the pages of their surgeon’s journal. This can be seen clearly in the way that all three surgeons all refer to the enslaved Africans on board – in those written both before and after the Act.

In all three journals, the enslaved are referred to with a number, which was assigned according to the gender and age group that each individual fit into, i.e. “Man no. 1” or “Girl no. 4.” These numerical assignments were given when an enslaved person needed to be given medical attention or to be written about in the journal, and as a result they proceed continuously through the books, beginning at 1 in each category and increasing as new patients are seen by the surgeon.[87] This identifying number is dropped, though, when the death of that person is marked down in the surgeon’s book: at that point, they become “one man,” or “one woman,” as in “Buried one man of the flux.” This removal of any identifier, even a numerical one, further reinforces the idea of interchangeability of Africans that permeates these texts, and also the transactional nature of this voyage. It is clear that this system is not one that prioritizes the individuality of Africans; it is one that identifies them only as objects to be briefly discussed and then reduced from a person to a note on a list – having already been reduced to a number from the beginning. This is particularly notable in comparison to the way that the crew members are referenced in these journals: almost always by name, certainly with a title or occupation if no name is present, and often with their hometown or country included. These are personal, human identifiers – something never once given to an enslaved person in any of these books. This does not change after Dolben’s Act.

The transactional nature of this system is also highlighted by the method of organization used in these journals. As was mentioned in the introduction to these documents, both Bowes and Bushell – the two post-1788 journals – use a tabular system which could be described as a proto-spreadsheet. The table records the day, the number of slaves alive, their gender and age groups, the number dead, and the total on board. This method allowed the surgeon to keep track of the number of slaves he should have on board at any given moment. This system, which remains remarkably consistent across these journals, is similar to the common accounting system known as “double entry bookkeeping” which was popular in the eighteenth century. Double entry bookkeeping allows for the tracking of the financial gains and losses, such that at the end of some period they may be tabulated to ensure that the numbers balance, much like a checkbook. This similarity, and the implication that the slave ship system was adapted from this system for financial accounting, reinforces the deeply economic nature of the work of a slave ship surgeon. This also can be contrasted with the way that passengers were recorded as being on board ships during the same period. Passenger manifests listed a person’s name, home county, home town, age, sex, and more. These manifests resemble double entry bookkeeping only in their tabular format – there is no equivalent of an “in and out” record keeping system, no column for those who had perished. Passenger manifests look much more similar to the tables at the back of Bushell’s journal, those printed for use in his record keeping of the crew’s health and disease. These tables record the name, station, and age of the crew member, with a column for the date of their death or recovery – a date, to be entered once, not a running tally of the number of living and dead. This would be known, of course, by the surgeon, who could keep track in his mind of the crew members who were alive and those who had perished – something not done for the enslaved, who were instead reduced to numbers on a list when they passed away.

The ways in which the enslaved were insured and used as payment, as well as the manner in which they were identified and kept track of in these surgeons’ journals, are evidence of the ongoing process of dehumanization that slave ship surgeons participated in. After the implementation of Dolben’s Act, none of these elements changed, highlighting the fact that the Act was unsuccessful in ameliorating the evils of the slave trade. In fact, the bureaucratization of the surgeon’s record-keeping which the Act required emphasized the transactional and inhumane nature of medical practice and of the slave trade more broadly, exacerbating issues of human objectification. This is what we can see from a superficial reading of these texts. But perhaps the incentives in Dolben’s Act to minimize the ship’s mortality rate, or even the requirements that the surgeon be certified and that his journal be copied and stored, acted as enough motivation for the surgeon’s actual, medical treatment of the enslaved to be held to a high standard. To test this theory, we may turn to a deeper, more quantitative reading of Daniel Bushell’s journal, a reading that will allow us further insight into his treatment of his enslaved patients.

A Quantitative Lens: On the Journal of Daniel Bushell

Bushell’s journal provides an interesting context in which to pursue the quantitative portion of this research, as it is split into two sections: “Sick Slaves” and “Sick Journal of Ship’s Crew.” In attempting to determine the extent to which the regulations in Dolben’s Act impacted surgeons like Bushell, we can examine the cost of drugs administered to the sick enslaved in comparison to sick crewmen. Were similar kinds of drugs used across the two groups of people, or was there a noticeable difference? Were more or less expensive drugs used on enslaved Africans? My methodologies are described in Appendices One and Two.

To answer these questions, I studied the two sections of Daniel Bushell’s journal and recorded the names of all of the medications used in treating each group of people. I created lists of the drugs used by Bushell to treat his patients during his time aboard the Alice; each consisted of approximately 30 drugs and can be seen in Figure 4. These two lists varied considerably even at first glance. I then found as many of those drugs as possible on the drug manifests described above. For each medication, I calculated a standard price of “pence per ounce,” which could be compared across medications. I then calculated the average prices of each of two lists of medications, and discovered that the medications used by Bushell on the crew of the Alice were, on average, 37% more expensive than the medications he used to treat the enslaved Africans who were on board. The 32 medications that Bushell gave to crew members had an average price of 7.97 pence per ounce, while the 33 drugs used for the treatment of enslaved Africans averaged 5.86 pence per ounce. Some of these medications were the same, such as common drugs like Glauber’s Salt or “Sal Glaub.” and pulverized rhubarb, or “Pulv. Rhei,” but 40% of those drugs used on the crew, and 38% of the medications used on enslaved people, were unique to that category. In each of these categories there were four and five drugs, respectively, that I could not find a price for and which were not used on the other group and therefore would impact these averages.

These data are compelling on their own, but there are a number of confounding variables that must be accounted for: primarily, the question of what Bushell was treating his patients for. If they had been suffering from different illnesses, perhaps the difference in the prices of medications could be explained without a correlation to race. However, it is clear that this is not the case when the symptoms discussed in Bushell’s text are examined: in the entire journal, there is exactly one symptom suffered by a crew member that is not also described as afflicting an enslaved person. There appear to be two main illnesses which spread throughout the Alice during this voyage. One is gastrointestinal: its symptoms are “violent purging,” “severe gripping” or flu-like symptoms, which would have included fever, “evacuating bloody, slimy stools” sometimes “involuntarily,” and “no appetite.” The second seems to have both pulmonary and full body symptoms, including “great pain in the head and stomach,” “pain in the breast,” “severe cough,” “languid” and “costive” (or slow) behavior, and, in the case of one crew member, spitting up a “frothy bloody matter” – this is the only unique symptom between the two groups in the whole journal. Bushell identifies this later disease as phthisis, or tuberculosis.[88] These two sets of symptoms dominate the book, infecting both enslaved people and crew members.

There are three instances of an enslaved man suffering from something besides these two illnesses: one from scurvy, a second from yaws, and third from inflammation of the gums.[89] The majority of the drugs used to treat these three symptoms are common to other treatments in the journal. However, three are particular to these ailments which only afflict enslaved people while on the Alice: “Manna,” a dried plant, “Flor. Sulph.,” or flowers of Sulphur, a powdered sulfur product, and “Tonic of vitr. Acid,” or a tonic of vitriolic acid, also a Sulphur-based product. These three medications are all significantly cheaper than the average price of medications used on the enslaved, which was 5.86 pence per ounce. In contrast, many of the medications that are given to only the crew members – all of which are being used to treat symptoms also described in the enslaved people on board – are significantly above even the higher average for the crew, of 7.977 pence per ounce. “Aqua Menthae Vulg.,” “Spirit of Lavender,” and “Confecto Cardiaca” are three examples; they cost 36, 12, and 10 pence per ounce, respectively. Though this must be true for the laws of averages to apply, it is worth iterating as an independent finding as well.

In summary, Daniel Bushell’s journal includes two distinct kinds of medical treatment. Faced with two groups of people suffering from nearly identical symptoms, he treated crew members of the Alice with more expensive medications than he administered to the enslaved people on board. Bushell effectively withheld more expensive drugs from the enslaved, choosing to treat the same symptoms with cheaper medications. The result of this differing treatment is unsurprising: during the voyage to St. Vincent, all of the crew members who became ill recovered, while all but one of the enslaved people died. The result of Daniel Bushell’s inconsistent treatment of these two groups of people was death for ten enslaved Africans on board the Alice, all of whom passed away while crew members with identical symptoms survived.

This finding, of course, raises the question of Bushell’s possible motivations for this discrepancy in treatment. The first explanation which comes to mind refers back to the complex insurance policies taken out on the human cargo of most slave ships. Perhaps Bushell cared less about the survival of the enslaved because the ship’s insurance would compensate the captain and merchants for their loss. However, in all maritime insurance codes, insurers were not held liable for the loss of spoiled goods by “natural wastage” or, when this policy was extended to the slave trade, “natural death.”[90] In the context of perishable goods, this meant that an insurer would not have to cover the cost of food or products which spoiled over the course of the journey; for the slave trade, this meant that enslaved people who died of sickness while on board would not be covered by insurers.[91], [92] The prevalence of this policy means that it would be quite unlikely for Bushell to have believed his enslaved patients would be covered by his insurance if they died, as insurers were almost never held accountable for deaths as a result of sickness.

Perhaps there were different financial incentives for Bushell’s differing treatments. Surgeons were paid with a salary, a small amount of money for each slave sold at market, in privilege slaves, and, post-1788, in bonuses from Dolben’s Act if the mortality rate was lower than 3 percent.[93] The components of this pay structure that would have been most lucrative for the surgeon were his privilege slaves and the bonuses, if applicable, from Dolben’s Act. Early on in the trade, being paid in a privilege slave meant that the surgeon would be allowed to select between one and three individual slaves to sell as his own at the end of the voyage. As each of these slaves, usually able-bodied men, could sell for between £50 and £100, and given that the average salary for a sea surgeon was £4 per month, with each voyage lasting between ten and eighteen months, this was a handsome sum.[94] However, as the trade went on, the logistical issues with this version of a privilege slave became clear – what if the selected slaves died or were injured on the journey? As a result, over the course of the trade the system changed such that the surgeon would be paid as though each of his privilege slaves were valued at the average sale price for the ship’s slaves.[95] This meant that if a surgeon was granted two privilege slaves as part of his payment, and the average sale price for all of the slaves on board was £75, he would be paid £150. This was a massive sum for someone in this world of work: by comparison, a naval surgeon made around £100 per year.[96]

This payment based on the average sale price of the enslaved means that some surgeons were more willing to allow the sickly to die instead of allowing them to reduce the average price of the entire ship’s human cargo. One such incident was included in Thomas Clarkson’s narrative of the abolition of the trade, in which he quoted a surgeon James Arnold, who sailed in 1785 and 1786. Arnold said that there had been an emaciated boy on his ship at the time of port in St. Vincent whom the first mate decided to hide on board and allow to starve to death instead of “expose[ing] him to sale with the rest, lest the small sum he would fetch in that situation should lower the average price, and thus bring down the value of the privileges of the officers of the ship.”[97] It is thus possible that Bushell would rather have allowed those ten slaves to die instead of having them arrive at port sick and bring down the price of his privilege slaves. However, this becomes a less likely explanation when considered in the context of the Dolben’s Act bonus system. If he did not allow those ten slaves to die, Bushell would have been more likely to qualify for a bonus of up to £20, which would likely have been greater than the difference between his profits from his privilege slaves with and without a lower average.[98] In other words, the bonus would have almost certainly been more money, and as he sailed after 1788, Bushell would have prioritized this over the minimal reduction of the average that the ten sick slaves would have caused.

It seems, then, that neither of these financial explanations provide valid reasoning for Bushell to have treated his African patients differently from the crew of the Alice. What remains to explain his behavior is the possibility of a scientifically racist construct of differential treatment. If this journal had been written in the nineteenth century, this would be the most reasonable and immediate conclusion; however, given its origin in the early 1790s, this would in fact be a surprising and even novel example of scientific racism at play in British medicine. For the majority of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Hippocratic humoral and environmental medicine dominated medical theory in Britain. In this conception of illness and medicine, the etiologies of disease had most to do with the environment a person found themselves in and the humoral intricacies of the individual.[99] Racial difference was not a core focus of this understanding of disease. Andrew Curran argues that the philosophy of disease shifted as a result of an Enlightenment-era focus on the science of race, which developed into the peak of scientific racism in the nineteenth century. The origins of this change can be found in the texts of philosophers and naturalists, though, not in the work of the British medical institution – whatever theory did exist on the medicalization of race was reserved for the most educated in Britain, and was likely not accessible to the actual practitioners of medicine in the late eighteenth century. Medical textbooks, lectures, and educational tools from this period did not reflect theories of scientific racism, but instead remained focused on the Hippocratic theories of disease discussed above.[100]

When, by the mid-nineteenth century, the scientific shift which Curran describes did overwhelm previous understandings of disease, it was a change complexly intertwined with the processes of the abolition of the trade across Europe. [101] However, in the Americas the cohabitation of whites and Africans had resulted in a much earlier focus on racial origins and patterns of disease. As early as the mid-eighteenth century, white physicians began to develop racialized theories of susceptibility to diseases such as yellow fever, a reality which centers colonial slave societies in the early development of scientific racism.[102] These ideas eventually intermingled with nineteenth-century European medicalized racism.

It is possible that Daniel Bushell’s reasoning for differential treatment of his Black and white patients was a theory of racialized medicine. If this were indeed the case, it would suggest that the trans-Atlantic slave trade may have operated as an early point of entry into the British medical field for colonial theories of racialized science. The time that slave trade surgeons spent landed in the “new world” may have served as an opportunity for the early transfer of these ideas, and Bushell’s journal may be evidence of this phenomenon. One of the other limited examples of early racialized medicine in Britain can also be found in the writings of a mariner-surgeon; Saakwa-Mante argues that John Atkins’ 1734 text The Navy-Surgeon includes a racialized discussion of the disease known as “sleepy distemper” or African Trypanosomiasis.[103] Though Atkins sailed before our most concrete examples of racialization of medicine in the colonies, it is not impossible for him to have participated in a similar process as Bushell may have been later in the 1700s.

Conclusion

Sir William Dolben certainly believed himself to be motivated by the “cause of humanity” in his attempts to regulate the slave trade.[104] But however pure the motivations of Dolben and his colleagues were, the resulting Slave Trade Act of 1788 was a set of regulations that failed to address any of the most core issues with the British slave trade. The Act did nothing to address the violence and abuse at the hands of the ship’s captain and crew, nor did its attempt to increase the amount of space allotted to each enslaved person even approach a truly humanitarian result – that could only have been achieved, of course, by the abolition of the trade. The other area in which the Act attempted to alter the trade was by regulating the behavior of the surgeon on board the slave ship. The regulations included did not at all impact that cycle of violence in which surgeons participated. It is clear from the content of journals kept by surgeons both before and after the Act that there was no impact on the root issue of the surgeon’s behavior: his constant dehumanization of his patients. Furthermore, a quantitative analysis of Daniel Bushell’s journal shows that he treated his African patients with different medications than his white patients, providing further evidence of the ineffectual nature of Dolben’s Act in its attempts to minimize mistreatment on board slave ships.

As possible financial explanations for Bushell’s differential treatment of his patients appear hollow, we are left with the possibility of this journal demonstrating the early permeation of scientifically racist ideas into British medicine. A final option worthy of note is that there could be no explanation at all for Bushell’s behavior, as it is possible that this quantitative analysis does not accurately reflect the human nuances of Bushell’s work aboard the Alice. As was noted in earlier discussions of a “numbers game” approach to this history, the numbers can only tell us so much. They tell us very little when separated from the history and lived context of the slave trade. However, when a numerical analysis is taken together with a discussion of the less quantifiable – but no less concrete – components of surgeons’ journals like Daniel Bushell’s, it becomes more difficult to deny the possibility that the slave ship’s ongoing dehumanization and abuse of Africans may have seeped into the ways in which British slave ship surgeons saw and treated their patients. This fundamentally flawed component of the institution of the slave trade was not touched by a single regulation in Dolben’s Act; no portion of that legislation would have impeded this kind of racially-motivated medical abuse at the hands of a slave ship surgeon. As Member of Parliament Charles Fox said of the Act, as "horrible as it yet left the situation of the poor slaves in their transport, it was the best bill which could then be obtained.”[105] Slave ship surgeons’ journals provide new insight into just how horrible that situation was, and reveal the impotence of Dolben’s Act in its attempts to ameliorate the terrors of this “most crying evil.”[106]

Appendices

Appendix One

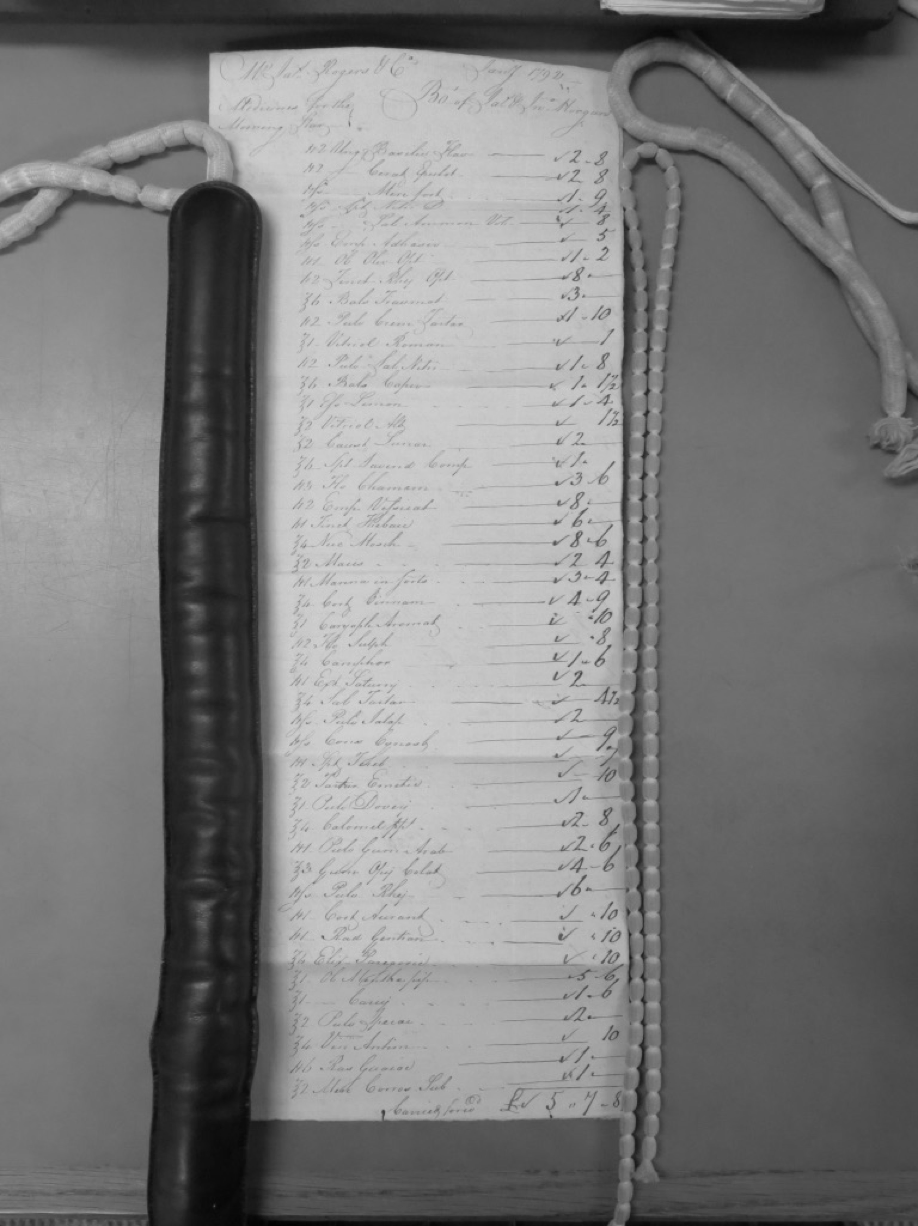

A Note on Drug Manifests

Though surgeons’ journals are the key kind of primary material investigated here, there was a second group of primary sources that played an important role. Again thanks to Dr. Carolyn Roberts, I have images of eight drug manifests of slave ships that set sail in the 1780s and 1790s (see Figure 6 for an example). These lists are, in essence, receipts – written by the apothecary from which the ships’ surgeon would purchase drugs for the voyage. They list the quantity of the medication being purchased, the name of the drug, and the price for which that quantity was purchased. I was able to use these manifests to gain a better understanding of the medications that were commonly used on slave ships during the period from which these journals originated, as well as in my quantitative analysis, which is described in Appendix Two.

Appendix Two

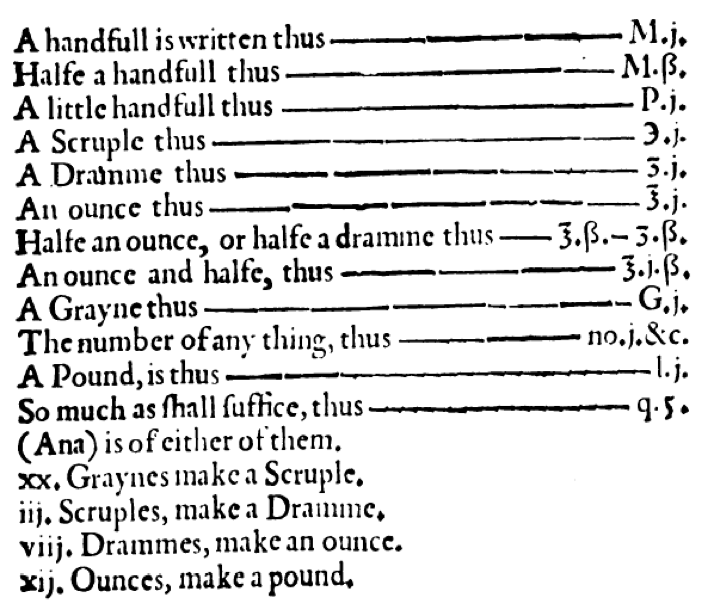

Methods of Analysis