Volume 16: January 26, 2021

The Second-Best Bed

By London Johns

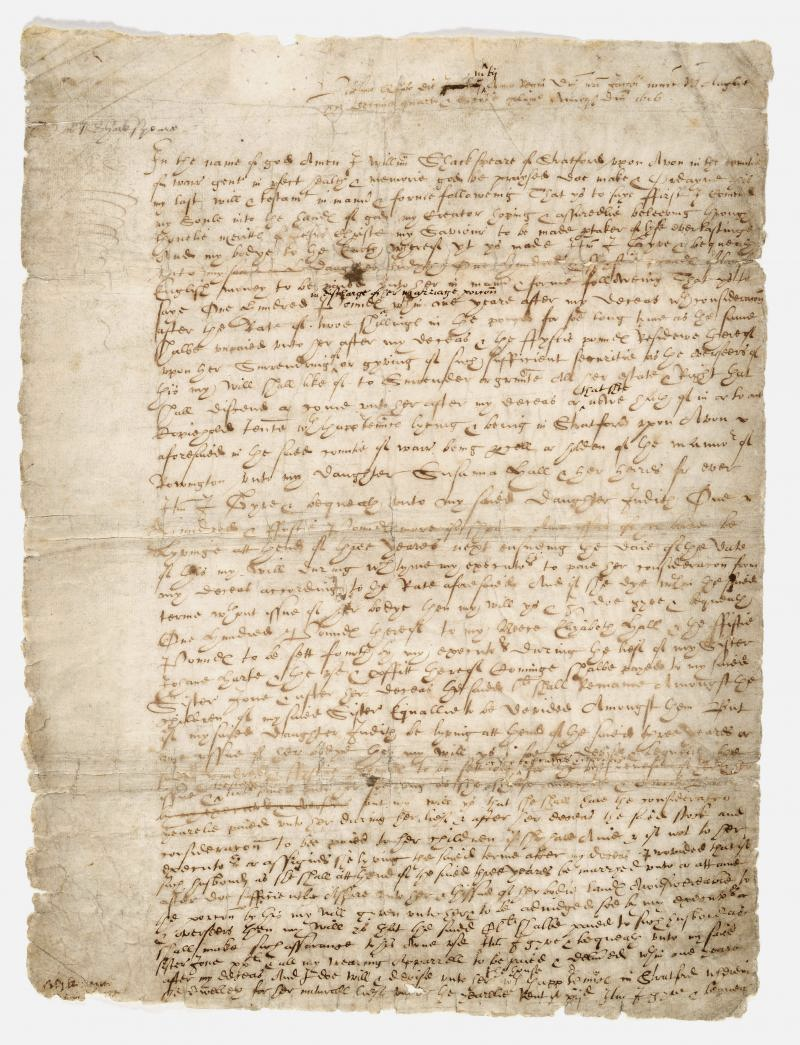

In the winter of 1616, William Shakespeare, who had retired to live with his family in Stratford-upon-Avon, drafted his will. In March, he revised the document; from the shakiness of his signature, it appears that he was already very sick. A month later, he died. Shakespeare’s will was unusual in several ways, but the most controversial was that he only left one thing to his wife, Anne Hathaway: the “second best bed with the furniture” (Shakespeare and Collins). This strangely cold way of addressing Hathaway in his will has invited much debate about whether Shakespeare and his wife were at odds when he died, or whether this section of his will could have had a more sentimental purpose than it appears at first glance.

Though Shakespeare drafted his will in January of 1616, he revised it only two months later to respond to his daughter Judith’s recent marriage. He left most of his property to his children, Susanna Hall and Judith Quiney; money and clothes to his sister Joan Hart; and silver plate to his granddaughter Elizabeth Hall (Nelson et al.). He also left his properties in Stratford and London to Susanna, various objects to Judith, Joan, and Thomas Combe, 26 shillings and 8 pence each to friends for mourning rings, and £10 to “the poor of Stratford” (Shakespeare and Collins). To his wife, however, Shakespeare left only one thing: “the second best bed with the furniture” (the furniture meaning the curtains and covers of the bed) (Senn). Compared to the treatment of other members of Shakespeare’s family in his will, leaving Hathaway only a bed seems like mockery. Is it possible that Shakespeare giving his wife the bed was more considerate than it appeared?

To understand how a bed could be significant, it is necessary to examine exactly what Shakespeare meant by the “second best” bed. One popular theory suggests that the best bed in the house was reserved for guests, and Shakespeare and his wife slept in the second-best bed instead. ‘Anne Hathaway’, a sonnet by Carol Ann Duffy, builds upon this idea: Anne Hathaway and Shakespeare were in the second-best bed while 'In the other bed, the best, our guests dozed on, / dribbling their prose' (qtd. in Scheil 66). If this was the case, leaving his wife the second-best bed would have been a sentimental gesture; in Elizabethan England, the marital bed was “a uniquely important possession within the household” (qtd. in Ackroyd 484). However, this interpretation doesn’t seem likely given the wording of the will. For one thing, Shakespeare was very precise in his words, both in and outside of his plays. Even his epitaph was written with a purpose -- to prevent the movement of his bones from his grave to make room for other bodies. It is unlikely that he would overlook the mocking connotations of both the phrase “second-best” and the fact that the bed was the only item in his will passed down to his wife. Secondly, while “second-best” was occasionally used in Elizabethan wills, it was far from common. Much more common were affectionate phrases like “loving” or “well beloved” (Ackroyd 484). “Best” and “second-best” were occasionally used to clarify which of several objects the will was referring to, as in a will from 1573 that included that a woman should be left a “second best featherbed for herself furnished, and one other meaner featherbed furnished for her maid” (qtd. in Schoenbaum 302). However, though both this document and Shakespeare’s will called a bed “second-best”, the 1573 will also instructed that the widow receive twice the income that she would have from the original marriage settlement, and her husband noted that he “would have her to live as one that were and had been my wife” (Schoenbaum 302) -- a lovely idea, and one very different from the brief, detached note about Hathaway in Shakespeare’s will, which reads almost as an afterthought.

A final aspect of the mention of Anne Hathaway in Shakespeare’s will that has been framed as proof of scathing intent is the position of the note on the page. The instructions about which of Shakespeare’s possessions were to be left to his wife were written as a smaller note between two lines of the will, as if it had been forgotten and then written back into the will after the rest of the document was complete. Anne Hathaway’s section of the will was not the only one written between lines; several friends to whom Shakespeare left money to buy mourning rings were also written into the will in this way (Schoenbaum 302). These mistakes could have been caused by forgetfulness, but it is equally possible that it was not Shakespeare’s mistake at all, and the lawyer writing down Shakespeare’s wishes simply skipped over these instructions and went back later to include them (Schoenbaum 302).

Though Shakespeare did not explicitly leave anything else to his wife, she could have inherited some of his property through custom, without it having to be written into his will. If another arrangement was not stated in the will, widows in London typically received a third of their husbands’ land and property, and by church and common law a widow was entitled to a third of her husband’s land (Hogrefe 101). Perhaps Shakespeare saw no need to put this policy into writing, and “the second-best bed” was simply a sentimental addition to Hathaway’s assumed inheritance. However, the right of widows to inherit one third of their husbands’ property was only a custom in London, and did not extend to Stratford. Most Stratford wills included a mention of how much of her husband’s property a widow would inherit after his death, sometimes in vague terms such as “the residue of my estate” (qtd. in Schoenbaum 301). Shakespeare was not living in London at the time of his death, nor when he wrote his will, so there is no reason to believe that his will would follow the London custom; compared to other Stratford wills, Shakespeare’s will leaving only his bed to Hathaway was very strange.

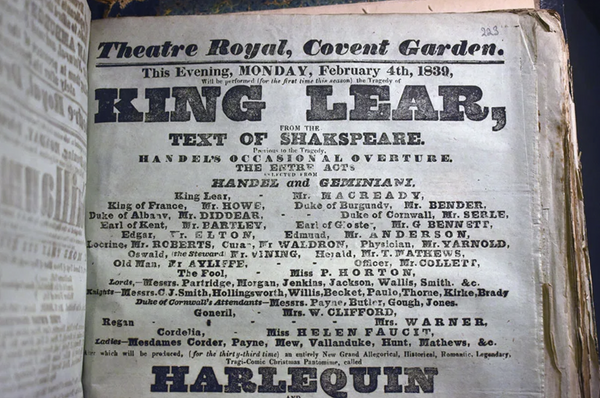

The lack of affection that Shakespeare’s will seems to demonstrate between him and his wife in some ways corroborates what little is known about their relationship. Shakespeare and Hathaway’s three children were born in the 1580s. At some point between 1585 and 1592, Shakespeare began working in London, and from 1592 until approximately 1611, when he retired, Shakespeare travelled back and forth between Stratford-upon-Avon, where his family lived, and London, where he worked (Reid et al.). The journey to London took at least three days, so even if he stayed in Stratford for as long as possible, Shakespeare must have spent a substantial amount of time away from home (Reid et al.). Perhaps the simplest explanation for Shakespeare’s coldness towards his wife in his will is the most accurate: that their relationship was complicated and often distant.

The brief, unsentimental way in which Shakespeare wrote about Anne Hathaway in his will has prompted many to seek explanations that do not paint Shakespeare as an uncaring spouse. Some wonder if the fact that Shakespeare left most of his property to his daughter Susanna might suggest that Hathaway was unable to take care of herself when he died, and that he expected her to live with their daughter. Others suggest that the bed referenced in the will was a valuable heirloom belonging to Anne Hathaway’s family. Either of these theories would protect an idealistic vision of Shakespeare’s relationship with his wife, but there is no evidence to suggest that either of them are true. While it was likely not an intentional insult, Shakespeare’s unusual note about his wife was certainly not an affectionate gesture.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Shakespeare: the Biography. 2006th version, London: Chatto & Windus, 2005, Internet Archive, archive.org/details/shakespeare00pete/page/484/mode/2up?q=second+best.

Hogrefe, Pearl. “Legal Rights of Tudor Women and the Circumvention by Men and Women.” The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, 1972, pp. 97–105. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2539906. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

Nelson, Alan H., and Folger Shakespeare Library staff. “William Shakespeare's Last Will and Testament: Original Copy Including Three Signatures.” Shakespeare Documented, 25 Mar. 1970, shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/node/110.

Reid, Jennifer, et al. “When Did Shakespeare Go to London?” Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/podcasts/lets-talk-shakespeare/when-did-shakespeare-go-london/.

Scheil, Katherine. “The Second Best Bed and the Legacy of Anne Hathaway.” Critical Survey, vol. 21, no. 3, 2009, pp. 59–71. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41556328. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

Schoenbaum, Samuel. William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. Oxford University Press London, 1927, Internet Archive, archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.186170/page/n319/mode/2up?q=second+best.

Senn, Mark A. “Shakespeare and the Land Law in his Life and Works.” Real Property, Trust and Estate Law Journal, vol. 48, no. 1, 2013, pp. 111–216. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24570832. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

Shakespeare, William, and Francis Collins. “Shakespeare's Last Will and Testament: Made 25 March 1616, Proved 22 June 1616. .” The National Archives, Kew, UK, The National Archives, Kew, UK, 25 Mar. 1616. https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/node/110