Written by Isabella Yang, SY 21'

Edited By Lica Porcile, BF 21'

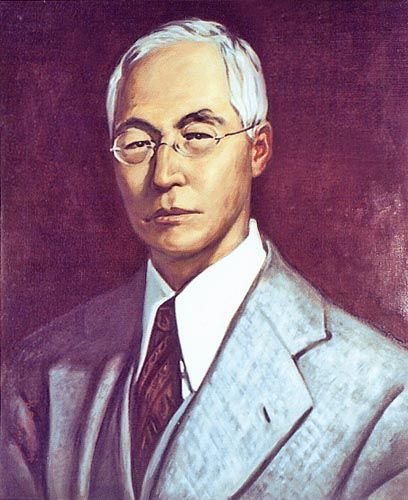

Tucked in the corner of a mezzanine-level bookshelf in Sterling Library’s East Asia Reading Room is an aged book with dark covers; on its spine are printed the simple words “Gifts of Yale Association of Japan.”[i] A reader flipping through its pages will soon recognize the majority of its contents as object accession numbers carefully laid out on the pages next to each other, followed by descriptive texts. On the inner cover are the words “Prepared by K. Asakawa, 1945.” This is the official catalog, a “self-published typescript volume,”[ii] of the 1935 Yale Association of Japan gift, known today as the Beinecke’s YAJ Collection, compiled by Kan’ichi Asakawa, one of the first people of East Asian descent to receive a Ph.D. from Yale and one of Yale’s first Asian faculty members.[iii] In 1945, Asakawa was still the leading scholar of Japanese Studies at Yale, and this compiled volume provides detailed information on each object and displays Asakawa’s ostensible effort to rearrange the collection’s taxonomy; the document was presumably a public document intended for the entire university community to read and research on.

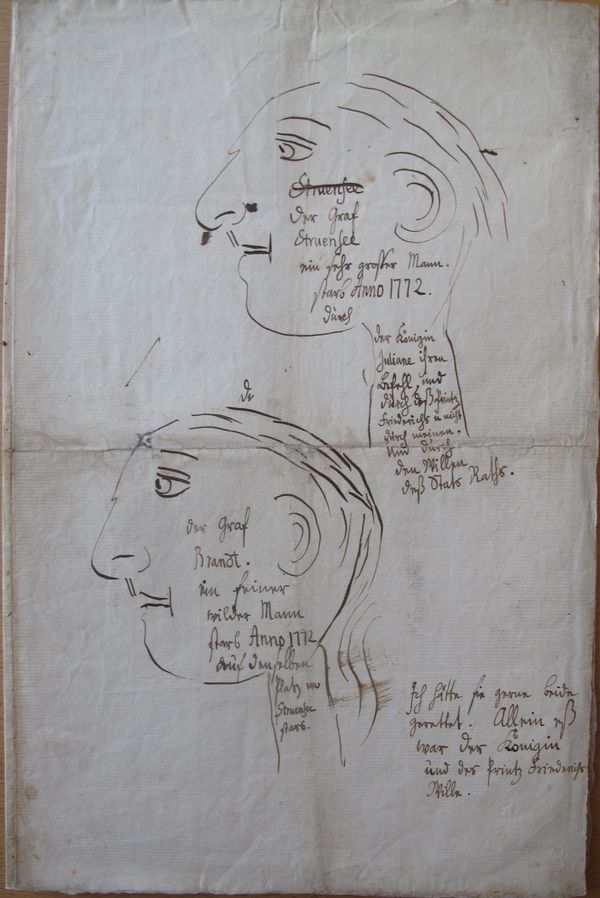

This catalog, as well as the back story of the YAJ gift, is closely related to two other primary sources in Yale’s possession: a letter sent to Asakawa in 1934 from Ōkubo Toshitake, a notable alum who was then a Japanese senator as well as president of Yale Association in Japan (also known for being the son of one of the founders of modern Japan), and another catalog from 1935 named Nihon Bunka Zuroku (Illustrated Catalog of Japanese Culture).[iv] The former provides a context for the gift’s arrival as well as its general contents, and the latter is an illustrated catalog of representative objects in the gift compiled by the Association. While all three documents describe the gift extensively, Asakawa’s catalog, written ten years after the gift’s arrival, contains valuable information on changes over time, on both the gift sender’s and recipient’s sides. One striking discovery in the “general comments” section is that the big 1935 gift was not the YAJ’s last contribution to Yale, for new gifts continued to be made throughout the next decade and were added to this catalog: for instance, Asakawa noted that through Ōkubo’s efforts a reproduced copy of famous Japanese medieval politician Fujiwara no Michinaga’s diary, the Mido Kwan-paku Ki, was added to the collection.[v]

This is remarkable as 1935-1945 marks the most severe deterioration in US-Japan relations, and the continuous gift-making effort of Japan’s Yale-educated elites could indicate a persisting interest in amending deteriorating national relations via cultural exchange.

Asakawa, being a Japanese American caught in the tensions of World War II, was already growing increasing weary of foreign affairs. However, there was one project he had been carrying on for over two decades, which in his opinion would help to establish a proper understanding of Japanese, and in general East Asian, culture among the Yale audience: the building of a “Classical and Oriental Museum.” As early as 1921, he had written to a friend in Japan on the expansion of library buildings, that “one of these buildings will be the Classical and Oriental Museum, according to our present plan, which should house all the collections regarding the classical civilization of the Greek and Latin races and of the Oriental peoples, and contain lecture seminar rooms, as well as offices for the various professors.”[vi] The preface of a Yale Association of Japan directory from 1922 also states that one of the association’s main goals was to fundraise for the “Oriental Museum,” and the subsequent gift of objects was also made with this purpose in mind.[vii]

There is no source stating so clearly why the “Oriental Museum” Asakawa and the YAJ initially envisioned did not become a reality, but the project was possibly cancelled due to the growing tensions between Japan and the United States and the subsequent concerns on whether the school should direct its resources to foster understanding with a country that was already enemies with the United States. In the end, Asakawa got one room in Sterling Library to hold the Japanese collection, instead of a full “Oriental Museum.” However, from the way he compiled the catalog, it is apparent that Asakawa still expected everything to be exhibited, as detailed “exhibition cards” were made in English for each object. One of the key themes in his re-compilation of this catalog was, according to Asakawa himself, the “special needs felt at an American university.”[viii] The taxonomy was rearranged: while Ōkubo’s letter indicated that the objects were put in five general categories according to facture (hand-written calligraphy, printed work, reproduced copies, Chinese & Korean books, furniture), Asakawa categorized the objects not by facture but by theme.[ix] His new taxonomy resembles a lot more an introduction to a culture, with religion separated from literature, and arts from “useful arts,” intended for his American audience to gain a better systematic understanding of Japan. “Progressive” themes that might be of interest to American audiences were specifically picked out: for example, objects representing “education” were accentuated, with words from figures like the modern educator Fukuzawa Yukiji celebrating equality included, and “women’s education” was also introduced as its own section.[x] Other themes that might directly facilitate US-Japan interactions, like representations of practical activities like the tea ceremony or sword-making, were categorized as “useful arts” and separated from other artworks.

The exact point in time when the catalog was published would be intriguing to explore, as its preparation coincides with the last year of World War II. The year “1945” could be either mark Asakawa’s futile attempt to restore hope at the height of war, before the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or him seeing cultural understanding as an important step to make post-war amends.

With the continuous additional gifts given to Yale from the YAJ between 1935 and 1945, it would also be interesting to study what kinds of additional gifts are given and if they had any patterns as the impeding war made national relations tenser than ever. One more thing to be considered is the editing history of this catalog: on this printed copy in the East Asia library, there are often seen edits made in blue ink, adding long marks on the Japanese pronunciations, adding and removing words, correcting numbers. Were those edits made by Asakawa himself? If not, had anyone else been involved with this effort? A record of how Yale and its libraries have handled this collection and who has been involved could also reflect the university’s attitude towards this Japanese gift as US-Japan relations developed over the last century. Overall, this document gives its reader a small yet valuable glimpse of a compromised attempt to foster cultural understanding at a time of cultural division, a narrative still applicable and even prevalent in the world nowadays.

Endnotes

[i] Sterling Library, DS821 Y225+.

[ii] Ellen H. Hammond, “A History of the East Asia Library at Yale University,” 9.

[iii] “Asakawa Kan'ichi.” Asakawa Kan'ichi | The Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University. Accessed August 5, 2020. https://ceas.yale.edu/asakawa-kanichi.

[iv] Yale Japanese Club [1870-1922], 1907-1922, MS 40, Series III, Folder: 296; YAJ 0.1.

[v] Asakawa, Kan’ichi. Gifts of the Yale Association (New Haven: 1945), 3.

[vi] Asakawa Kan'ichi to Z. Morikubo, Dec. 2, 1921. “Letters by Asakawa,” Asakawa Kan'ichi Shokanshū (Tōkyō: Waseda Daigaku Shuppanbu, 1991), 10.

[vii] Librarian, Yale University, Records (RU 120). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/12/archival_objects/1937760 Accessed August 05, 2020.

[viii] Asakawa, Kan’ichi. Gifts of the Yale Association (New Haven: 1945), 5.

[ix] Kan'ichi Asakawa Papers (MS 40). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/12/resources/3017 Accessed August 05, 2020. Okubo’s letter has not been fully transcribed, but on the third page of his letter the five categories are marked as such: “A)肉筆モノ宸影。寫經。古文書。墨跡。手鑑及短冊帖 B) 啟經。利本類 C) 複製本 D) 支那・朝鮮本 E) 調度品類。”

[x] Asakawa, Kan’ichi. Gifts of the Yale Association (New Haven: 1945), 84-86.