Written by Morgan Baker, JE 21'

Edited by Ale Andres Campillo, JE 21', Mary Tate, BK 21', Charlie Mayock-Bradley, PC 23', and Ellie Burke, SM 24'

Introduction: Yoga Mythology and the Limits of Cultural Appropriation

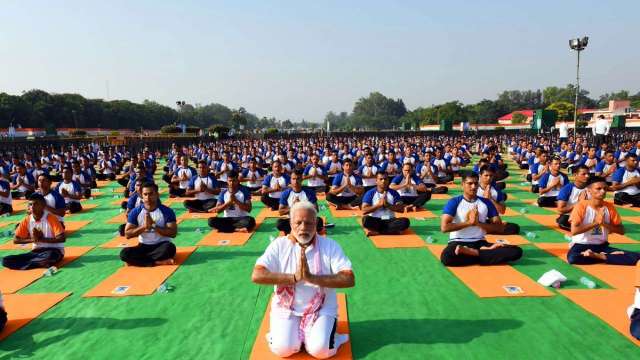

My 200-hour yoga teacher training program began on June 21, 2019, at the summit of East Rock Park in New Haven, Connecticut. After a brief orientation meeting, I and seventeen other yoga teachers-to-be joined a growing mass of people on a well-manicured lawn in the shadow of a hilltop veteran’s monument. Dozens of people dressed in spandex and harem pants had gathered for a public class in celebration of the International Day of Yoga, a United Nations-sanctioned day on which hundreds of thousands of people engage in public demonstrations of yoga in cities across the globe. Together, we performed sun salutations and breathwork patterned after the change of the seasons under the light of an early summer golden hour. Hours earlier across the Atlantic, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Baba Ramdev, and other political officials and yoga celebrities led hundreds of thousands of people across India in similar sequences of yoga postures as part of that nation’s observance of the holiday.[i]

Early the next morning I was seated on a stack of blankets listening to our lead trainer’s introduction to our month-long intensive. To my pleasant surprise, we began our first moments together not with the basics of a downward facing dog, but with a lecture on the history of the practice we were to spend our time exploring together. In a whirlwind hour, I absorbed a narrative about yoga’s prehistoric beginnings, the emergence of the Bhagavad Gita (“The most renowned of the Yogic scriptures”), and a “Classical” period of yoga defined by the transcription of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Under the header “A Brief History of Yoga,” my training manual explains how this millennia-long incubation period blossomed into what we might call “modern yoga”:

"In the late 1800s and early 1900s, yoga masters began to travel to the West, attracting attention and followers. This began at the 1893 Parliament of Religions in Chicago, when Swami Vivekananda wowed the attendees with his lectures on yoga and the universality of the world’s religions… The importation of yoga to the West still continued at a trickle until Indra Devi opened her studio in Hollywood in 1947. Since then, many more western and Indian teachers have become pioneers, popularizing hatha yoga and gaining millions of followers".[ii]

Hallmarks of yoga’s popularly accepted history include references to early archaeological evidence of meditation postures, appeals to yoga’s origins in ancient, sacred texts, and the implication that Western yoga is the result of a unidirectional transmission of existing South Asian yoga systems from East to West. In these ways, the history I received in my yoga teacher training was not unlike the history you might receive if you asked the person teaching community classes in your neighborhood park or the woman calling out postures during mat-to-mat sessions in your local boutique studio.

My teacher training program took pride in its holistic approach to yoga practice even beyond this prelude. My teachers derided practices that advertised themselves primarily as workouts, and our program included hours of discussion about racial equity and cultural appropriation in the yoga industry. In later yoga philosophy classes, my teachers explicitly encouraged my fellow trainees and I to ground our practice in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali - its ethical precepts especially.A strong philosophical basis, we were told, comprised a core part of a practice that appreciated, rather than appropriated, yoga’s roots in South Asia. As the woman at the front of the room, the lead trainer and studio owner, closed my training program’s opening lecture, she became abruptly serious: “I’ve devoted my life to creating a place where people come to know themselves spiritually. If you’re here to teach a fitness regime, come talk to me.” None of this moralizing was required for the program to meet Yoga Alliance’s certification standards; their lectures were far more than perfunctory gestures. On the whole, my teachers treated questions of power and privilege with great care.

As a then-rising junior at Yale with academic and personal interests in the politics of healing and wellness, I became fascinated with the question of how I could teach (and practice) yoga ethically, respectfully, and responsibly - even more so given the accusations of cultural appropriation frequently levied against yoga teachers.

In popular discourses, “cultural appropriation” describes a phenomenon in which a more dominant social or cultural group takes up the practices, customs, or aesthetics of another social or cultural group, often in a way that is exploitative or misrepresentative. A 2016 blog post in Everyday Feminism, “8 Signs Your Yoga Practice Is Culturally Appropriated,” writes further:

"Neglecting to recognize the origins of what you’re using is a classic sign of cultural appropriation. You may not mean to participate in the system of white supremacy by doing this, but it’s part of how the system operates – by removing any trace of people of color from the positive things we create".[iii]

Similarly, the Hindu American Foundation’s “Take Back Yoga” campaign argued vehemently in the early 2010s that American yoga practitioners have paved over yoga’s supposed Hindu origins, “in favor of more palatable terms like “yogic,” “Eastern,” or even “Vedic”.[iv] In response, yogis against cultural appropriation have produced a slew of popular articles intended to educate yoga teachers and practitioners on the “real” history of yoga. The Everyday Feminism article, the “Take Back Yoga” campaign, and the history lecture I received in my yoga teacher training program were all part of this cultural wave.[v]

Through the repeated calling up of origins and roots, accusations of cultural thievery prime the listener to receive corrective histories that explain something like how what we imagine as “ours” is, in reality, rightly “theirs,” and that we have genericized or sanitized the object in question in the process of claiming it for ourselves. The logic of cultural appropriation thus assumes a number of things to be true: that we all mean the same thing when we speak about “yoga”; that there is a clear, unbroken link between ancient South Asian yogas and this modern yoga; and that Western yoga is too often a bastardization of distinctly South Asian practices - religious ones at that, depending on who you ask. Many of these corrective histories leave us with a picture of modern yoga that belongs to the cultures of South Asia and (or) Hinduism in its purest and most proper forms.

In one sense, it is true that yoga is a South Asian practice. James Mallinson and Mark Singleton’s Roots of Yoga tells us that there were, and are, indigenous practices that called themselves “yoga” with origins in South Asia. Nevertheless, scholarship on the history of modern yoga from the past twenty years gives us reason to interrogate the relationship between these indigenous yogas and modern yoga. Anya P. Foxen argues to this end that many American “yoga” practitioners are actually involved in a practice with closer ties to twentieth century harmonial gymnastics, physical culture movements, and Western esotericism than premodern South Asian indigenous yogic practices. According to Foxen, “there is a Western history of practice here that was overwritten by the imported language of yoga, thereby becoming invisible. In this form, it has continually been used to inform and occasionally to colonize the category of Indian yoga.”

As such, we might better understand much of modern American yoga as Western esotericism packaged in the aesthetics of South Asia.[vi] This repackaging still amounts to an act of gross cultural exploitation, though perhaps of a different character than popular understandings of yoga’s history might suggest.

Calls to “honor yoga’s roots” often demand that we reproduce histories of premodern yogas. Yet paradoxically, a focus on the ancient and the premodern lends itself to a certain nearsightedness, obscuring the deeply transnational valences of the popularization of modern yoga in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Most popular yoga histories do not adequately convey that modern yogas are cultural productions that have always been fluid, shapeshifting with the demands of the globalized marketplace. Far more than a concern borne of intellectual elitism or nitpicky semantics, the lack of nuance in popular discourse makes yoga teachers and practitioners likely to reproduce histories of yoga that are Orientalist, neo-colonial, or otherwise problematic when considered within the sociopolitical context of South Asia. To reflect this concern, this paper synthesizes recent advances in yoga history to contextualize the potential for harm inherent in dominant histories of modern yoga philosophies and practices.

My invocation of the plural is intentional. Joseph Alter describes books, magazines, and pamphlets published on yoga and its history as “pulp nonfiction” that “[defies] synthesis”[vii] : for every story one could tell about what yoga is, dozens of others would argue otherwise. Alter writes of yoga gurus and masters that:

"If any one of the others were to read what another had written, he or she would be as likely to disagree as agree with what is claimed. Many authors write as though they are the only person writing on [Yoga] with any authority, and that what they are saying is new. Yet if there is one single thing that characterizes the literature on Yoga, it is repetition and redundancy in the guise of novelty and independent invention".[viii]

James Mallinson and Mark Singleton’s 2016 anthology of several classical “yogic” texts, Roots of Yoga, likewise shows us that this polyvocality is more continuity than change with regards to yoga in antiquity. In this way, “yoga” is more a floating signifier – an object without actual referent – than a concrete practice that can be observed, understood, and traced across different temporalities and geographies. Though imprecise, I use the term “yoga” to reflect the fact that “yoga” is what the practitioners I engage with believe they are doing. My use of this term does not presume that this constellation of practices forms any coherent whole with any cogent history. In fact, quite the opposite. We cannot guarantee that we mean the same thing when we speak about yoga. And as we will see, in the absence of critical scholarship on the genealogy of modern yogas, discourses of cultural appropriation reproduce yoga histories that leave proponents and practitioners likely to perpetuate other epistemological and cultural violences.

For many Westerners, the idea of tapping into an ancient, mystic, esoteric practice that promises the cessation of suffering is intensely seductive. It is precisely this aura of mysticism that renders yoga and yoga spaces vulnerable to ahistoricism, anti-intellectualism, and propagandization. In contrast, my approach to yoga and its popular mythologization is, like Alter’s, one of moderate skepticism. In adopting this orientation, I understand that I am occupying the decidedly unfun position of the “feminist killjoy” or “affect alien.”[ix] Yet it is only by doing away with mystique, by staying vigilant to the ramifications of the stories we tell about yoga, that we can hope to embody a truly ethical and responsible yoga practice.

In this paper, I consider how certain common historicizations of globalized yoga practice function as propaganda for Hindutva, a violent and politically powerful ideology of Hindu nationalism with a drive to purge India of its Muslim (and, to a lesser extent, Christian) citizens. I begin first by using ethnographic and historical data to contest the commonly accepted narrative about what yoga is, who created it, and who it belongs to. I then argue that modern yoga’s attachment to “classical” texts, Sanskrit, and the concept of peace allow it to signify in concert with the (a)historical and exclusionary national narrative of Hindu nationalism, even as diverse actors work to affirm yoga’s secularity. I close with a call to action for yoga teachers, studio owners, and students who wish to adopt a more anti-oppressive orientation to yoga practice.

Is yoga Indian?: Swami Vivekananda and the transnational origins of Raja Yoga

The history I gleaned from my yoga education makes two central claims about yoga: first, that archaeological evidence proves yoga as we know it existed prior to its arrival in the United States. And second, that Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902) was a master of this yoga and can be credited with bringing it to the West. Contemporary scholarship contradicts both of these claims.

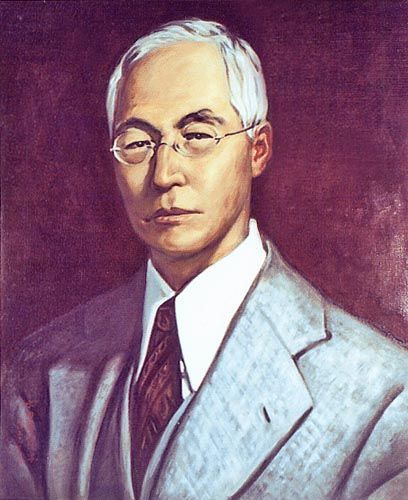

Popular sources often cite the “pashupati seal” as evidence of ancient, pre-modern practice.[x] Andrea Jain has argued that this claim, and that of modern yoga’s origins in the fifteenth century Rig Veda Samhita, is largely unsubstantiated. Assertions that yoga is rooted in later Upanishads, the Mahabharata, and the Ramayana are somewhat more legitimate. Still, the conflict between the many theological and philosophical systems present in these texts are vast enough to render such claims – that the yoga we practice today would be even somewhat recognizable to pre-modern practitioners – tenuous at best.[xi] Popular and scholarly narratives about the origins of modern yoga converge at the point of Swami Vivekananda’s speech at the 1893 Parliament of Religions in Chicago. From here, however, narratives diverge sharply again on the grounds of who Vivekananda was and what, exactly, he brought to America.

As an adolescent, Vivekananda was active in denominations of the Brahmo Samaj, a Hindu reformist sect. But to identify Vivekananda as flatly “Hindu” is to grossly misrepresent the degree to which his religious views pulled from thought exogenous to both orthodox Hinduism and South Asia. The “Neo-Vedanta” philosophy of Keshubchandra Sen (1838-1884), one of Vivekananda’s greatest influences, was heavily influenced by American transcendentalist philosophical movements. Vivekananda was also interested in Western philosophy and studied Kant, Hume, Spinoza, Mill, and others, “though reportedly not in great depth”.[xii] This infusion would later prove critical to Vivekananda’s ability to translate “classical” and “ancient” Hindu and yogic texts into the language and value system of the wealthy, coastal American milieu.

After the death of his spiritual teacher, Vivekananda traveled throughout the Indian subcontinent. Over the course of his travels, he became disappointed in how, by his observation, the country lacked a spiritual ethic. As a result of his sojourn, Vivekananda dedicated himself to rekindling India’s weakened spirituality. To do so, however, would require significant funding. In December 1892, Vivekananda wrote:

"To effect this, the first thing we need is men, and the next is funds. Through the grace of our Guru I was sure to get ten to fifteen men in every town. I next travelled in search of funds, but do you think the people of India were going to spend money! … Therefore I have come to America, to earn money myself, and then return to my country and devote the rest of my days to the realization of this one aim of my life. As our country is poor in social virtues, so this country is lacking in spirituality. I give them spirituality and they give me money".[xiii]

This is how, in July 1893, Vivekananda found himself in the United States set to attend the Chicago Parliament of Religions[xiv]: not as a guru of anything he or anyone else would have called yoga, but as a self-appointed envoy of a quasi-Hindu mission. On Elizabeth De Michelis’ telling, Vivekananda’s rise to the status of “yoga master” during these years was by and large accidental.

Tellingly, Vivekananda’s fabled speech at the Parliament of Religions does not mention yoga by name.[xv] The speech instead reflects his original intention: to garner American financial support for his version of Hinduism by presenting what he knew – a “Brahmo-oriented Neo-Vedantic esotericism” – in a package that would seduce and entertain. The fact that Vivekananda was not, in actuality, a Hindu monk upon his arrival posed little problem. According to De Michelis, the fact that he was from India was enough: “Oriental teachers…would be implicitly understood by romanticizing Westerners to be providers of genuine teachings, whatever their credentials. Vivekananda knew how to reinforce and make use of these sympathies”.[xvi] The platform of the Chicago Parliament of Religions exposed him to a field of American spiritual aspirants eager to learn so-called “practices,” none of which yet existed in Vivekananda’s rapidly expanding syncretic “yogic” philosophy. As he traveled the East Coast meeting with Christian Scientists and other often extremely wealthy groups of esotericists, Vivekananda “[grafted] the occultistic teachings that he came to know in America – and which he obviously found convincing – onto his own (already esotericized) interpretations of Hinduism”. Vivekananda’s encounters with American occultism eventually informed the development of Vivekananda’s Neo-Vedantic thought.[xvii]

Vivekananda would later synthesize this amalgamation of Eastern and Western thought into the book Raja Yoga, whose narrative continues to influence contemporary yoga teacher training programs. Raja Yoga is responsible for several (a)historical claims made about what yoga practice is, including the system of multiple yogas (karma yoga, bhakti yoga, raja yoga, and jnana yoga, all different modes of “worship” for different kinds of spiritual aspirants: “the rational, the emotional, the mystical, and the worker”)[xviii] and the instantiation of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali as yoga’s primary, authoritative text.[xix] While Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga does indeed pull much of its philosophy and many of its practices from premodern South Asian yogic traditions, DiMichelis argues that the book is so syncretic that it reflects the interests and desires of curious Americans far more than the transmission of the wisdom of an unbroken South Asian yogic lineage.

It is also important to note that something called “yoga” did actually exist in the United States prior to Vivekananda’s arrival. Earlier in the nineteenth century, Ida Craddock and Pierre Bernard taught and practiced what was then known as hatha yoga, a collection of practices derived from the “mystic-erotic techniques of tantra” that bears little resemblance to the postural “hatha yoga” practiced today. Many Americans saw Craddock’s hatha yoga as crass, vulgar, and barbaric. Vivekananda developed his system of raja yoga in ideological opposition to this nineteenth-century hathayoga; it was Vivekananda’s proselytizing that eventually sparked a “yoga renaissance” in both the East and West.[xx]Drawing from the work of Joseph Alter in Yoga in Modern India and Mark Singleton in Yoga Body, Andrea Jain argues that Vivekananda’s raja yoga merged with a global “physical culture” emerging in the early 20th century to produce modern postural yoga. In contrast to hatha yoga’s eroticism, “physical culture,” like that embodied by the YMCA in the United States, “provided a context in which physical fitness was perceived to enhance an ascetic and Protestant notion of self-control, moral development, and purity”.[xxi]

The first modern yoga schools, including the yoga systems of T. Krishnamacharya (1888-1989) and his students, B. K. S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois of Iyengar and Ashtanga Yoga, respectively, emerged in India beginning in the 1930s. These emerging yoga schools were the lovechild of the global turn toward physical culture and the yoga renaissance initiated by Swami Vivekananda and his syncretism. Yet it wasn’t until the 1960s, when “certain social changes enabled postural yoga advocates to flourish in the global fitness market,” that postural yoga crossed the Atlantic once more, where it merged with Vivekananda’s still quite counter-culture raja yoga and achieved spectacular levels of adoption.[xxii]

I discuss the work of Elizabeth De Michelis, Andrea Jain, and Joseph Alter at length because the history they present of Swami Vivekananda and yoga’s emergence in the United States stands at odds with dominant popular narrative. The yoga that Swami Vivekananda brought to America did not exist before raja yoga’s synthesis between 1893 and 1896 in the United States and its recreation through the first half of the 20th century in India. And, put simply, Vivekananda was neither a yoga master nor a Hindu monk in the ways popular histories encourage us to imagine. Vivekananda’s followers believed they were engaged in a pure, authentic, Indian cultural and religious practice. While it is the case that he drew from South Asian philosophies, American occultism and Neo-Vedanta deeply shaped the way he packaged these traditions. To this point, it is important to emphasize that the “Neo-” in “Neo-Vedanta” indicates the influence of American transcendentalism, rather than a more modern, yet still “purely” Indian, Vedantic philosophy.

This is not to say that we ought to skewer all yogas that have genealogical ties to Swami Vivekananda and Raja Yoga with accusations of inauthenticity. Nor is this to suggest that the practices set out in Raja Yoga amount to nothing more than snake oil. Modern yoga’s persistent popularity suggests that practitioners feel that their yoga practices do “work,” whether they account for these effects using magic, mysticism, esoteric beliefs, or (pseudo)-science. This practical efficacy is in no way diminished by the fact that its history is not what we might expect. Yet if it is the case that much of modern American yoga owes its existence to Raja Yoga and Swami Vivekananda’s globetrotting syncretism, modern yoga cannot be said to be essentially or purely “Indian” or “Hindu” - even as associated practices bear the stamp of South Asian cultures and aesthetics.

Is yoga Hindutva?: The (re)production of yoga as propaganda

Hindutva describes a strain of Indian Hindu nationalist ideology with origins in the 1920s that has escalated in popularity and influence since the 1980s. According to Parvis Ghassem-Fachandi, this nationalism is not based so much in Hinduism as religion as it is in Hinduism as a race or culture. Although India is a secular nation constitutionally speaking, Hindutva politicians and political organizations have agitated to circumscribe the Indian citizen as properly Hindu, at the often violent exclusion of those who identify religiously or culturally as Muslim or Christian.[xxiii] In India, Hindutva politics crystallizes in a number of formal political organizations, including the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), of which current Prime Minister Narendra Modi is a member.

Multiple scholars in the emerging field of critical yoga studies have argued that the International Day of Yoga is a tool of soft power for a Hindutva political machine.[xxiv] They disagree, however, on how well globalized yoga can serve this purpose given its strategic secularization. We might ask further how it is that modern yoga, a constellation of practices with both American and South Asian roots, can be incorporated as part of the symbology of a violent and exclusionary Hindu-Indian nationalism.

Popular yoga histories most often contend that modern yoga is a practice that is culturally, philosophically, and spiritually rooted in South Asia, de-emphasizing or omitting the fact that American fitness culture and Western esotericism have shaped yoga in its present form - even as often practiced in India.[xxv] This omission allows Hindu nationalist actors to co-opt modern yoga, claiming a practice that is familiar, unthreatening, and popular largely because of its American valences as an example of the best of India’s indigenous cultural products from a pre-Islamic golden age. Insofar as popular yoga histories avoid examination of modern yoga’s American roots, popular yoga histories bolster modern yoga’s utility as a vehicle of Hindu nationalist propaganda. This is not to say that all modern yoga amounts to is its weaponization by proponents of Hindutva. Rather, I offer this analysis as a provocation to begin thinking more critically about the effects of yoga mythologies and histories on the narratives that animate political violence in South Asia.

Yoga’s secularity and universality are foundational aspects of how yoga has captured bodies, minds, and spirits globally. As early as Swami Vivekananda, yoga promoters and practitioners from diverse backgrounds have gone to great lengths to argue that yoga is secular. Swami Vivekananda’s original intent in making broad claims to yoga’s (and Hinduism’s) universality and secularity was to leverage its aura of mysticism without alienating non-Hindu Western aspirants. Accordingly, the “secularization” of modern yoga is not a new phenomenon, nor is it evidence that yoga in the West has necessarily been “whitewashed” or stripped of its “true” substance. In fact, modern yoga’s universal and secular qualities were key selling points for Prime Minister Modi as he proposed the International Day of Yoga to the United Nations. The website for the United Nations-sponsored International Day of Yoga attests to this fact while offering a concise history of the practice that, given the history outlined previously, we ought to find suspect. Like many other histories, the UN’s account makes broad claims to yoga’s ancient origins in India without addressing the transnational cultural movements that led to its popularity.[xxvi] Even so, we might ask: what incentive did Modi, a member of a political party responsible for instances of religious violence, have to advance a secular practice?

To this end, Jyoti Puri argues that Modi’s speech at the UN was, in effect, an act of national branding that leaned on yoga as a discourse with the semiotic flexibility to “[advance] Hindutva’s exclusionary programmes at home while also navigating the imperatives of international politics, the needs of business and foreign investment, and other musts of neoliberal capital”. He puts forth that, in describing India, its history, and its potential contributions to the world, Modi leverages yoga to amplify a “chronicle of an ancient spiritually-oriented civilization” with continued relevance in the contemporary geopolitical order. In particular, Modi uses yoga to emphasize how India models peace, health, and spiritual enlightenment for the world. This historical narrative is one that Modi shares with Swami Vivekananda, the so-called father of yoga:

"Vivekananda paradoxically drew on European romanticist orientalists’ reconstructions of Indian history. Pivoting around selective Brahmanican scriptures, these European orientalist discourses provided him and others with the groundwork on which to construct anti-colonial but explicitly Hindu notions of the past. Embedded in these reconstructions were ideas of Hindu civilizational greatness, a golden period so to speak, that needed to be rejuvenated in order to combat colonial rule and Western hegemony".[xxvii]

Critically, this romantic, Orientalist vision of India is one that contemporary Hindu nationalists also hold. As Pankaj Mishra explains, British “discovery” of classical Indian cultural productions gave upper-caste Hindus an “invigorating sense of the pre-Islamic past of India”. A desire for this golden age pre-Islamic past is a significant motivating factor in Hindu nationalist Islamophobia; a yoga built on “classical” Sanskrit texts appeals to exactly this compulsion. As we have discussed, there is little historical evidence to support the claims that modern yoga as it is most commonly practiced is ancient, Hindu, or purely Indian. Yogas practiced in India are not exempt from this analysis. Given this, unqualified appeals to yoga as ancient, Hindu, or Indian in the context of the politics of the BJP ultimately invoke epistemologically violent renarrations of Indian history that function both to exclude Muslim Indians from the concept of the nation and motivate spectacular instances of violence.[xxviii] For proponents of Hindutva, it is only through the elimination of Muslim citizens through disenfranchisement, deportation,[xxix] and mob violence that India can be restored to its prior glory.[xxx] Mass asana demonstrations on precisely arranged saffron orange mats begin to take on a new gravity within this web of signification.[xxxi]

“Hindu origins” advocates like those involved in the Hindu American Foundation’s Take Back Yoga campaign argue – against historical fact – that yoga’s roots rest firmly within Hinduism. But we should not be most concerned with those who occupy this stance when considering modern yoga’s collusion with Hindu nationalist discourses. Surprisingly, proponents of yoga’s Hindu origins may actually contribute to modern yoga’s propagandistic potential. Hindu origins advocates serve as a strawman for those proponents of Hindutva who assert yoga’s secularism in concert with other more mainstream practitioners. [xxxii] In his 2004 book Yoga in Modern India, Joseph Alter recounts the belief of one of his subjects, an RSS-affiliated yoga master, that “the principles of Yoga are incompatible with RSS ideology, because Yoga is not limited to Hinduism”.[xxxiii] Nevertheless, prominent contemporary Hindu nationalist figures promote a secular yoga.

Presumably in response to proponents of the “Hindu origins” position at festivities for the International Day of Yoga in 2018, an article in The Hindu reaffirmed the claim that yoga is indeed secular:

"Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan lauded the greatness and benefits of yoga but said it should not be seen as part of any religious practice…Yoga could be practised by all, irrespective of caste and religion, Mr. Vijayan said, adding it should be done with a ‘free and secular’ mind. Yoga was an exercise and not part of any ritual, he said attempts were being made by some groups to “hijack” it in the name of religion. “This kind of false propaganda will only keep common people away from yoga and reduce its popularity".[xxxiv]

Proponents of both “Hindu origins” and “yogaphobic” (non-Hindu aversion to yoga based on the belief that yoga is a Hindu practice) positions both make claims to yoga’s Hindu origins in ways that threaten yoga’s secularism.[xxxv]Aavriti Gautam and Julian Droogan describe further the steps that Indian governments have taken – avoiding sun salutations in public demonstrations, publishing pamphlets – to advance the argument that yoga is secular (and therefore compatible with Islam).[xxxvi] In this way, advocacy for the Hindu origins of yoga only provokes further pronouncements of yoga’s secularism. At the conclusion of their article, Gautam and Droogan adopt a somewhat ambivalent stance regarding the significance of the tension between Hindu origins, yogaphobic, and secular camps for the strength of yoga as Hindutva propaganda. On their analysis it would seem that a yoga that is not explicitly Hindu cannot effectively serve the purposes of Hindu nationalism.

On the contrary, both Puri and I have argued that such an explicit association is unnecessary given the ways in which yoga’s popular mythologization and Hindu nationalist discourses converge. “Nowhere in his remarks did Modi use the word Hindu,” Puri writes. “But precisely because of the settled associations between antiquity, epistemology, and upper-caste Hinduism even outside of India, he didn’t have to” for his speech to the UN to reify Hindu nationalist accounts of Indian history and national heritage.[xxxvii] For those familiar with the grammar of Hindutva, Modi’s speech is instantly recognizable. Moreover, due to the temporal and political gap between “the roots of yoga” and what it has since become, mythologized, golden-age accounts of modern yoga’s origins can persist even as its present-day enactments become more distal to ancient indigenous South Asian yogas. Yet as yoga becomes increasingly “secularized,” “commodified,” and “whitewashed” by Indians and Westerners alike, so intensify accusations of cultural appropriation and inauthenticity. These accusations incite a retelling of what is too often a romantic, Brahmanical, Orientalist version of yoga’s history that lacks a critical understanding of the impact globalization had on the development of modern yoga in the twentieth century. In reproducing popular yoga mythologies, Western yogis unknowingly reproduce Orientalism and the ideology of Hindutva. And so the narrative persists.

As further evidence of the flexibility of Hindutva discourse, yoga need not be widely accepted as secular for the repetition of the assertion that it is secular to advance Hindu nationalism. Because yoga has been installed in the Indian (and, for that matter, American) cultural imagination as a national pastime and an endogenous Indian cultural product, Muslims who occupy a yogaphobic stance to yoga because of its proximity to, alliance with, or promotion by Hindu nationalists are vulnerable to accusations of a lack of patriotic spirit. For a group already politically marginalized and whose citizenship is in jeopardy due to the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act, this is a damning accusation. BJP and RSS investment in a purportedly secular yoga is not only a concession made to win Western favor. It is also, alarmingly, a way to gaslight Muslim Indians into participating in the reproduction of an ideology that seeks to eradicate their existence.

Conclusion: Meeting the monsters under the mat

The “Cultural Heritage” section of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s 2019 platform reads as follows:

"Since inception, the philosophy of the BJP is anchored in the civilizational ethos of India. As we build ‘New India’, we intend to actively invest in strengthening our cultural roots … [1] We reiterate our stand on Ram Mandir. We will explore all possibilities within the framework of the Constitution and all necessary efforts to facilitate the expeditious construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya…[8] We will further continue our efforts to promote Yoga globally as the world celebrates 21st June as the International Yoga Day. We will promote Yoga as a vital method to achieve physical wellness and spiritual rejuvenation across the globe and will continue to work towards training of Yoga practitioners".[xxxviii]

For most Americans, there is nothing particularly alarming about this cultural agenda. However, that the construction of a temple for the Hindu god Ram in Ayodhya remains the first cultural priority of the BJP betrays an unabashed attachment to an extended instance of Hindu mob violence that left two thousand people dead. The vast majority of those killed in the violence surrounding Ayodhya were Muslim.[xxxix]

Like “9/11” for Americans, “Ayodhya” recalls one of many flashpoint moments in the Indian national consciousness, cultural referents that have produced a grammar and vocabulary of Hindutva signification that can be recalled and exploited without explicit elaboration. The documentary film Ram Ke Naam (1992) – in English, In the Name of God – documents the kind of double-speak that Hindu nationalist politicians deployed throughout the course of the crisis. The film juxtaposes speeches by Lal Krishna Advani, the then-leader of the BJP, claiming “our [parade] will not start riots” with images of newspaper headlines documenting staggering death tolls along the path of the parade. Of Muslim Indians, the film captures one Hindu adherent boasting, “We can do anything to them…We’re prepared to fight.”

The BJP’s adoption of yoga-as-discourse is deeply strategic. Indeed, the coexistence of yoga, Sanskrit, and the construction of the Ram Temple on the BJP’s cultural platform indicates that the links between yoga and Hindu nationalism are neither implicit nor coincidental:. As Puri writes, “Yoga…provides a pathway for historicizing the nation, while simultaneously reaching into individuals’ hearts, minds, and bodies. Yoga functions both symbolically and materially, as the nation’s metaphor and its literal embodiment”.[xl] The purpose of the BJP’s yoga advocacy is to circumscribe the rightful Indian citizen as Hindu by speaking into existence a yoga that bills itself as universal, secular, and nonpartisan, but that nevertheless amplifies Hindu nationalist narrations of the nation. If denials of violence and displacements of responsibility characterize public-facing Hindutva political strategy, the mechanism by which yoga serves as propaganda cleanly adheres to Hindutva’s established ideology and methodology.

In How Propaganda Works, Jason Stanley writes, “The most basic problem for democracy raided by propaganda is the possibility that the vocabulary of liberal democracy is used to mask an undemocratic reality”.[xli] This is the work that yoga does in service of Hindu nationalism, albeit in the vocabulary of peace and global, transnational unity. In his 2014 speech to the United Nations, Prime Minister Modi capitalized on yoga’s connotations of peace and equity to advance half-hearted pronouncements of cooperation with the Muslim-majority states of Pakistan and Kashmir. Jyoti Puri reports further that in this same speech, Modi held up the country’s “charity and generosity” toward Pakistan and the Indian-occupied state of Kashmir, “even as the brutal state repression in Indian-occupied Kashmir [was] sidestepped”.[xlii] Similarly, in the wake of September 11, 2001, Pankaj Mishra notes how Hindu nationalists offered themselves to the West as compatriots in the fight against Islamic fundamentalism.[xliii]

We could call this stance anti-terrorism or pro-democracy. We could also recognize it as an instance of interest convergence motivated by Islamophobia. It is a testament to the success of yoga as propaganda that it can signify equity and peace while simultaneously being mobilized in support of Hindutva. This should be cause for concern and immediate action.

Postscript: Recommendations for practice

It is not necessarily the case that we should “cancel” yoga. Given yoga’s propagandistic potential, a more effective mode of intervention might be beginning to undo the narrative work that has been done thus far. While some of these recommendations are specific to those who share yoga with others, most are relevant to anyone who engages in yoga practice. A more responsible yoga practice must entail a radical honesty about the product that is being provided. As a start, yoga practitioners can collectively:

- Stop treating any singular yogic text as authoritative, including (and perhaps especially) the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Recognize instead the polyvocality of yoga and yogic practices in premodern India. Know where your practice diverges.

- Stop venerating “classical” systems of postural yoga, such as Iyengar and Ashtanga, on the basis of their authenticity or connection to “tradition”. Stop protecting gurus who abuse their students.

- Refuse to exploit an Orientalist mystique in your classes and studios. Investigate the histories and origins of metaphors of subtle body anatomy. Avoid attributing practices broadly to the “ancient yogis”.

- Explore histories of Western esotericism. Instead of assuming all modern yoga practice hails from elsewhere, begin to parse out the parts of practice that come from American religio-spiritual and cultural movements.

- Boycott the International Day of Yoga. Demand that the United Nations remove false, propagandistic claims about yoga from its website and programming.

- Revise yoga history lectures and curriculums to reflect what is known about modern yoga’s postcolonial origins. Be generous with this knowledge. Share it widely.

Endnotes

[i] Chandrashekar Srinivasan, “Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis Joins Ramdev On Stage At Yoga Day Event,” NDTV.com, accessed May 3, 2020, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/international-yoga-day-2019-baba-ramdev-and-devendra-fadnavis-lead-thousands-in-yoga-in-nanded-2056762.

[ii] Margot Broom and Breathing Room Yoga Center, “A Brief History of Yoga,” 2014.

[iii] Maisha Johnson and Nisha Ahuja, “8 Signs Your Yoga Practice Is Culturally Appropriated – And Why It Matters,” Everyday Feminism, May 25, 2016, https://everydayfeminism.com/2016/05/yoga-cultural-appropriation/.

[iv] Yoga Journal Editors, “Yoga’s Lost Hindu Roots,” Yoga Journal, accessed May 3, 2020, https://www.yogajournal.com/blog/yogas-lost-hindu-roots.

[v] I do not intend, here, to suggest that outcries against cultural appropriation in yoga are univocal. In “8 Signs Your Yoga Practice Is Culturally Appropriated,” the authors offer a critique of efforts like the Hindu American Foundation’s “Take Back Yoga” campaign. Other similar internal disagreements abound within popular and academic discussions of yoga and cultural appropriation.

[vi] Anya P. Foxen, Inhaling Spirit : Harmonialism, Orientalism, and the Western Roots of Modern Yoga (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020), 1-2.

[vii] Alter, Yoga in Modern India, xix.

[viii] Alter, Yoga in Modern India, xviii.

[ix] Sara Ahmed, “Happy Objects,” in The Promise of Happiness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

[x] See Georg Feuerstein, “The Historical Evolution of Yoga Is Exceedingly Complex and Scantily Researched.,” Yoga Journal, June 1987.

[xi] Jain, Selling Yoga, 6-9.

[xii] Elizabeth De Michelis, A History of Modern Yoga: Patañjali and Western Esotericism (New York: Continuum, 2004), 93–96.

[xiii] De Michelis, 108.

[xiv] Importantly for those of us who are not scholars of religion in the late nineteenth century, De Michelis notes that the Parliament of Religions was an “avant-garde intellectual manifestation of the activities of…cultic milieus”. This is, in part, how Vivekananda’s Brahmo Samaj was invited as an official representative of Hindusim. Once in Chicago, Vivekananda earned money by offering lectures for this same local “cultic milieu,” and lobbied the Brahmo Samaj to be declared a Hindu monk so that he could speak at the Parliament itself.

[xv] “Swami Vivekananda and His 1893 Speech,” accessed May 3, 2020, https://www.artic.edu/swami-vivekananda-and-his-1893-speech.

[xvi] De Michelis, A History of Modern Yoga, 111.

[xvii] De Michelis, 110–18.

[xviii] De Michelis, 124. It is worth noting, here, that this system of different yogis for different “kinds” of spiritual aspirants also runs somewhat parallel to the institution and ideology of caste.

[xix] De Michelis, 178.

[xx] Jain, Selling Yoga, 23.

[xxi] Jain, 38–40. In contemporary American urban centers, we might additionally draw parallels between Protestant ethics of self-control, moral development, and purity and the cultures of power and vinyasa yoga, barre, CrossFit, and other forms of boutique fitness. For a creative nonfiction take on this, see “Always Be Optimizing” in Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror.

[xxii] Jain, Selling Yoga, 38–40.

[xxiii] Parvis Ghassem-Fachandi, Pogrom in Gujarat : Hindu Nationalism and Anti-Muslim Violence in India (Princeton [N.J.]: Princeton University Press, 2012), 4.

[xxiv] See Jyoti Puri, “Sculpting the Saffron Body: Yoga, Hindutva, and the International Marketplace,” in Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism Is Changing India (London: C. Hurst & Co., 2019), 317–31; Aavriti Gautam and Julian Droogan, “Yoga Soft Power: How Flexible Is the Posture?,” The Journal of International Communication 24, no. 1 (2018): 18–36; and Patrick McCartney, “Stretching into the Shadows: Unlikely Alliances, Strategic Syncretism, and De-Post-Colonizing Yogaland’s ‘Yogatopia(s),’” Asian Ethnology 78, no. 2 (2019): 373–402, https://doi.org/10.2307/26845332.

[xxv] By “popular modern yoga,” I refer specifically to modern yogas with genealogical ties to Swami Vivekananda, T. Krishnamacharya, T. K. V. Desikachar, Pattabhi Jois, B. K. S. Iyengar, Yogi Bhajan, and others who popularized postural yoga and breathwork in the United States in the mid-to-late twentieth century. Photographs of Prime Minister Narendra Modi at previous International Days of Yoga show him engaging in various physical postures - including tree, locust, and serpent poses - that are mainstays in modern postural yoga classes.

[xxvi] United Nations, “International Day of Yoga,” United Nations (United Nations), accessed May 3, 2020, https://www.un.org/en/events/yogaday/.

[xxvii] Puri, “Sculpting the Saffron Body: Yoga, Hindutva, and the International Marketplace,” 324.

[xxviii] For examples, see the events surrounding the demolition of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in December 1992 and the 2002 Gujarat pogrom.

[xxix]“Citizenship Amendment Bill: India’s New ‘anti-Muslim’ Law Explained,” BBC News, December 11, 2019, sec. India, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-50670393.

[xxx] Pankaj Mishra, “Ayodhya: The Modernity of Hinduism,” in Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation, ed. Kamala Vishweswaran, First Edition (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2011), 191–93.

[xxxi] “Saffron Carpet Rolled Out For Modi to Mark Yoga Day,” News18, June 20, 2017, https://www.news18.com/news/india/saffron-carpet-rolled-out-for-modi-to-mark-yoga-day-1438615.html.

[xxxii] See “Yogaphobia and Hindu Origins” in Andrea Jain’s Selling Yoga.

[xxxiii] Alter, Yoga in Modern India, 149.

[xxxiv] “International Yoga Day: Rajasthan Records Biggest Yoga Gathering,” The Hindu, June 21, 2018, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/live-updates-international-yoga-day-observed-across-the-world/article24215787.ece.

[xxxv] For more on “yogaphobia,” see “Yogaphobia and Hindu Origins” in Andrea Jain’s Selling Yoga (2015).

[xxxvi] Gautam and Droogan, “Yoga Soft Power: How Flexible Is the Posture?,” 29.

[xxxvii] Puri, “Sculpting the Saffron Body: Yoga, Hindutva, and the International Marketplace,” 323.

[xxxviii] Bharatiya Janata Parry, “Bharatiya Janata Party Sankalp Patra Lok Sabha 2019,” April 8, 2019.

[xxxix] Mishra, “Ayodhya: The Modernity of Hinduism,” 195.

[xl] Puri, “Sculpting the Saffron Body: Yoga, Hindutva, and the International Marketplace,” 323.

[xli] Jason Stanley, How Propaganda Works (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2015), 11.

[xlii] Puri, “Sculpting the Saffron Body: Yoga, Hindutva, and the International Marketplace,” 327–29.

[xliii] Mishra, “Ayodhya: The Modernity of Hinduism,” 192.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. “Happy Objects.” In The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Alter, Joseph S. Yoga in Modern India: The Body Between Science and Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Bharatiya Janata Parry. “Bharatiya Janata Party Sankalp Patra Lok Sabha 2019,” April 8, 2019.

Broom, Margot, and Breathing Room Yoga Center. “A Brief History of Yoga,” 2014.

De Michelis, Elizabeth. A History of Modern Yoga: Patañjali and Western Esotericism. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Feuerstein, Georg. “The Historical Evolution of Yoga Is Exceedingly Complex and Scantily Researched.” Yoga Journal, June 1987.

Gautam, Aavriti, and Julian Droogan. “Yoga Soft Power: How Flexible Is the Posture?” The Journal of International Communication 24, no. 1 (2018): 18–36.

Ghassem-Fachandi, Parvis. Pogrom in Gujarat : Hindu Nationalism and Anti-Muslim Violence in India. Princeton [N.J.]: Princeton University Press, 2012.

“International Yoga Day: Rajasthan Records Biggest Yoga Gathering.” The Hindu, June 21, 2018. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/live-updates-international-yoga-day-observed-across-the-world/article24215787.ece.

Jain, Andrea R. Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Johnson, Maisha, and Nisha Ahuja. “8 Signs Your Yoga Practice Is Culturally Appropriated – And Why It Matters.” Everyday Feminism, May 25, 2016. https://everydayfeminism.com/2016/05/yoga-cultural-appropriation/.

McCartney, Patrick. “Stretching into the Shadows: Unlikely Alliances, Strategic Syncretism, and De-Post-Colonizing Yogaland’s ‘Yogatopia(s).’” Asian Ethnology 78, no. 2 (2019): 373–402. https://doi.org/10.2307/26845332.

Mishra, Pankaj. “Ayodhya: The Modernity of Hinduism.” In Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation, edited by Kamala Vishweswaran, First Edition. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2011.

News18. “Saffron Carpet Rolled Out For Modi to Mark Yoga Day,” June 20, 2017. https://www.news18.com/news/india/saffron-carpet-rolled-out-for-modi-to-mark-yoga-day-1438615.html.

Puri, Jyoti. “Sculpting the Saffron Body: Yoga, Hindutva, and the International Marketplace.” In Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism Is Changing India, 317–31. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2019.

Srinivasan, Chandrashekar. “Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis Joins Ramdev On Stage At Yoga Day Event.” NDTV.com. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/international-yoga-day-2019-baba-ramdev-and-devendra-fadnavis-lead-thousands-in-yoga-in-nanded-2056762.

Stanley, Jason. How Propaganda Works. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2015.

“Swami Vivekananda and His 1893 Speech.” Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.artic.edu/swami-vivekananda-and-his-1893-speech.

United Nations. “International Day of Yoga.” United Nations. United Nations. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.un.org/en/events/yogaday/.

Yoga Journal Editors. “Yoga’s Lost Hindu Roots.” Yoga Journal. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.yogajournal.com/blog/yogas-lost-hindu-roots.