Interviewed by Henry Jacob, SY '21

Transcribed by Yassi Xiong, DP '22

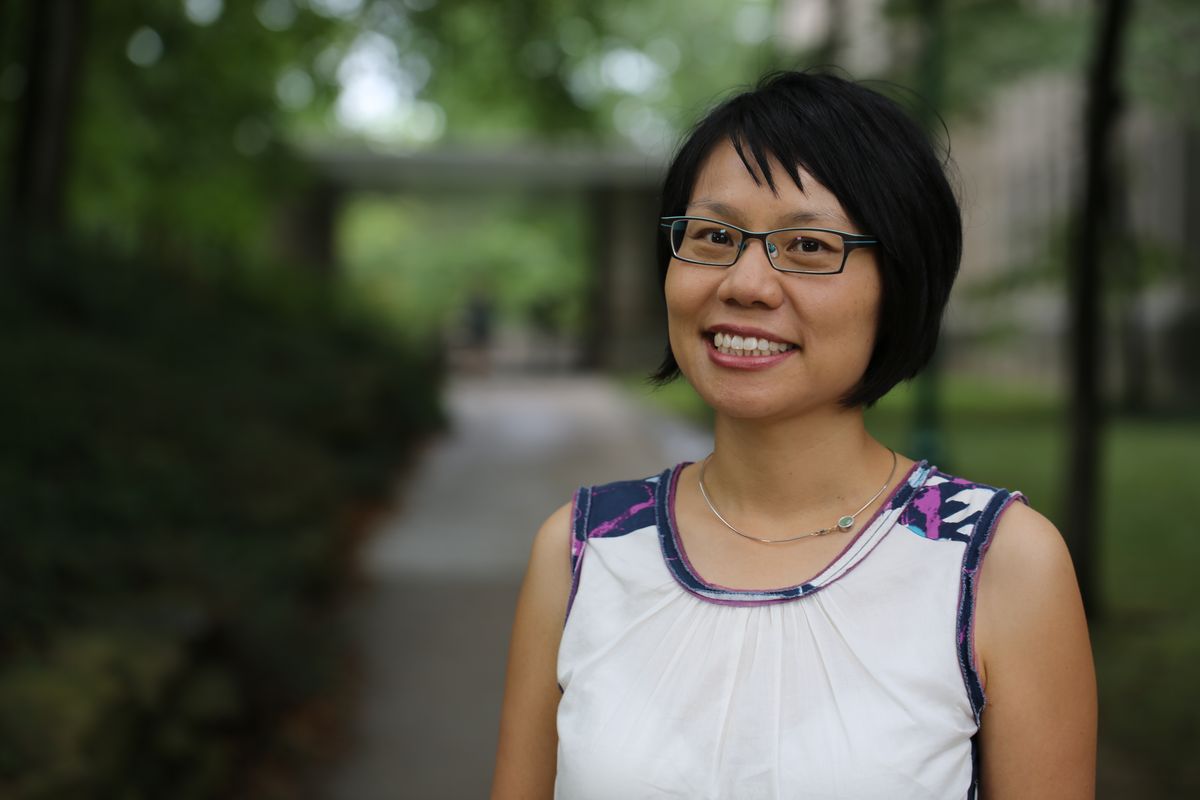

Ellen Wu, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of History at Indiana University Bloomington. Her research, teaching, and writing interests focus on race and immigration in the United States. She is the author of The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority (Princeton University Press, 2014). This interview was conducted on July 14, 2020.

YHR: In The Color of Success, you trace the shifting perceptions of Asian Americans in the U.S. from the 19th to 20th century. What led you to this project? Did you take a specific course as an undergraduate or as a graduate student that brought you to this subject?

Ellen Wu (EW): As an undergraduate I decided to study Asian American history. One question guided my reading of the scholarship during the 1990s and the early 2000s: how did Asian Americans change from being the “Yellow Peril” or, in the case of South Asians, the “Brown Hordes” in the US imagination?

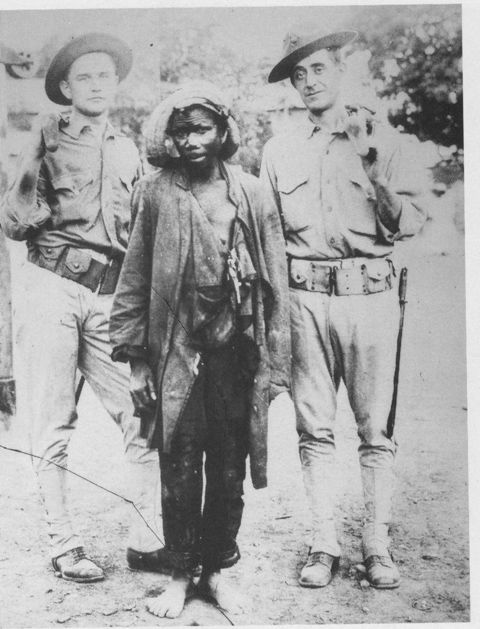

From the middle of the 19th century through World War II, Asians in the United States were considered aliens. Regardless of who they behaved or what they believed—they might be Christians, fully patriotic, family-oriented and so forth. Scratch off the surface you would find something threatening lay within. But by the 1950s and 1960s Americans began to celebrate Asians as exemplary citizens, the so-called “model minority.” I wanted to understand how Asians in America underwent this complete reversal.

My first seminar in grad school was on postwar American society with Professor George Chauncey. This class got me interested in the big changes in race sparked by World War II.

I found three main engines that drove the change in perception of Asian American after World War II. Asians themselves sought to make the United States a viable place to live. Before World War II, if you weren't born in the US and had Asian ancestry, you couldn’t become a naturalized citizen. You faced segregation in employment, in housing, in schools. You couldn't marry whomever you wanted. You always faced the threat of racialized violence or public ridicule. For these reasons, many Asian Americans wanted to be recognized as fellow Americans — they wanted to chance become neighbors, friends, and coworkers just like white people had.

I studied the two largest ethnic Asian groups at that time, the Japanese and the Chinese. The Japanese American side encountered a stunning turnaround. During World War II, the federal government removed between 110,000 and 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry and put them in concentration camps.

The federal authorities ran the camps in consultation with the Japanese American Citizens League, a select group of Japanese American who acted on behalf of their entire community. (They were very controversial at the time because there wasn’t agreement among Japanese American prisoners about the best course of action to take.) They decided on a plan for re-entry for Japanese Americans, to facilitate essentially what they thought of as “assimilation” into American society. By that, they meant fading into the white middle class, not returning to their former homes on the Pacific coast and not creating their ethnic enclaves like Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo.

This re-entry plan had two parts. The first revolved around the military. If Japanese Americans fought for the United States, they could prove that they had put their lives on the line—they were not the enemy alien. This was a hugely controversial among Japanese Americans—many were bitterly opposed to this plan. The second part of this re-entry plan was what they called “resettlement,” essentially encouraging Japanese Americans to move away from the west coast and settle in the Midwest, on the east coast, and recreate their lives anew with the hope that scattering would speed up their assimilation.

The federal authorities partnered with churches, YMCA, and other well-intentioned organizations, but perhaps ones who didn't understand how traumatic this process would be. The whole resettlement project was a mixed bag, and certainly plenty of people returned to their homes on the west coast after the war. But some braved the circumstances and moved out to places like Chicago, Cleveland, and New York and stayed.

During World War II, social scientists embedded themselves in the camps, treating the prisoners as subjects for ethnographic study. After World War II, Japanese Americans fascinated many social scientists, journalists, and politicians for a different reason. By the late 1940s and 50s, journalists and social scientists observed what looked to be Japanese Americans’ “progress,” describing their resilience, rebounding, and recovery from the wartime traumas. I call these narratives “success stories.”

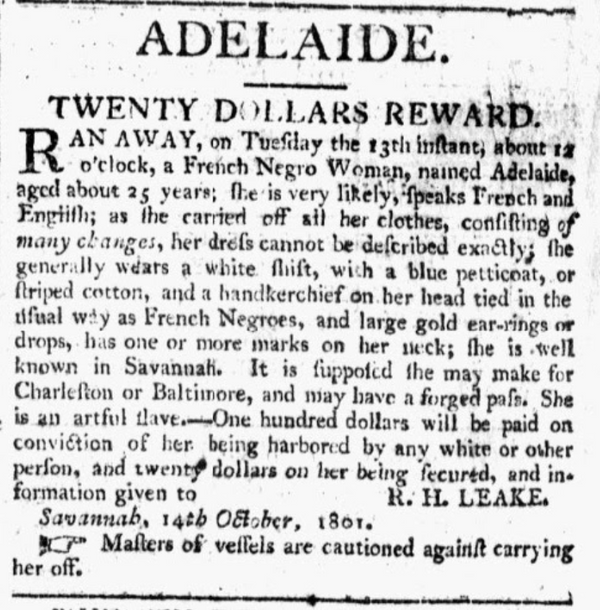

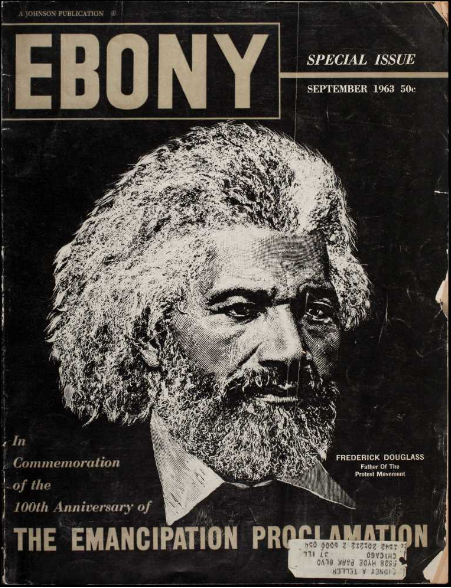

At first, Japanese American success stories became of great interest to liberal policymakers and academics, people like Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who sought a solution to what they call the “Negro problem.” Their interpretations of Japanese and Chinese American history suggested that Asian American “success stories” might hold the key to solving the urgent problems that Black Freedom Movement activists had made it impossible to ignore. By the mid 1960s, these comparisons became very pronounced, creating a dichotomy between Asian Americans and African Americans.

YHR: You used the phrase, “scratching off the surface.” I like the image of superficiality these words evoke. Please speak a bit more on the gap between U.S. racism at home and its representation abroad.

EW: That’s what interested me about this particular history—the tension between what actually happened and the story of it. In the 40s and 50s, many well-intentioned liberals believed that assimilation was the best path for racial minorities in the United States, that people of all backgrounds just needed to follow in the footsteps of the white middle class.

YHR: As you mentioned, trauma remains a central theme here. This is a question not just of theory but of physical and symbolic pain.

EW: Yes, I agree. One of my favorite parts of the research that I did for that book emerged from my seminar paper for Professor Chauncey’s course on post war society.

That was the story of Japanese Americans zoot suiters. Why they're so interesting to me, first of all, is because what most people know about zoot suiters is this youth culture that was really significant in Mexican American and African American communities. At that time, I had not heard of Asian American, Japanese American zoot suiters. These kids—mostly young men, but some young women too— learned about zoot suiting from their Mexican American neighbors. Others learned in the WWII camps, picking things up from Japanese Americans who came from different parts of the west coast, some rural and some urban.

This becomes a trend among some of the young people in the camps. When the federal War Relocation Authority piloted the resettlement program, zoot suiters became a problem. Because you might say they were assimilating, but they were doing the wrong kind of assimilation. They were assimilating to black and brown youth culture.

The government did not have this form of assimilation in mind. Government officials conducted exit interviews for potential resettlers. They would, either in the form of a question or in the form of a command, say “do you promise not to hang out with large groups of Japanese in public or speak Japanese language in public” or “do you promise not to stick out and wear conspicuous clothing and hairstyles”? I read the implied threat as that of zoot suiters—the duck tail haircuts and the flamboyant fashions.

I loved researching this slice of social history. I found these incredible first-person verbatim transcripts of interviews that social scientist Charles Kikuchi conducted with young people leaving the camps for Chicago in 1943 to 1944. Speaking with 1940s slang, they explained this traumatic experience of moving to an unknown city where they didn’t know anyone and weren’t supposed to see each other.

YHR: As you discuss in The Color of Success, these developments for Asian Americans ran alongside the civil rights movement. How did the model minority myth also discredit African Americans’ call for racial justice?

EW: By the mid to late 1960s, a new racial common sense about “Orientals” emerged. Ideas about Asian Americans coalesced around a certain set of themes: reverence for family, value for education, and communities that don't have problems of crime or welfare dependency. They're not out in the streets protesting and making trouble. They're keeping their heads down, they're working hard, and they're succeeding. It’s important to note that this racial common sense did not accurately describe real-life circumstances for all Asian Americans.

That bundle of ideas allowed policy makers to compare Asian Americans and African Americans. In the book, I make the case that during the mid 60s Asian Americans emerged as this definitively not-black racial group in American society. Americans could invoke this example to dismiss calls to fix deep structural problems. It's a way to say: “No, the problem is you. It's your culture. It's your behavior. It's not how we’ve set up our laws, economy, and political system.”

YHR: Our conversation has revolved around the friction between the past we experience and the past we record. How do you seek to reconcile these competing visions of history to provide a single narrative in The Color of Success?

EW: I'm very interested in the tension between theory and practice, how these relate or don't relate to one another, and how ideas themselves allow for the possibility of action. From my research I know that ideas matter, that they have consequences. Today, if we can reshape the ideas, we might end up with different results.

YHR: For me, exploring the liminal space between the remembered and the forgotten stands as one of the most exciting and important tasks of the historian.

EW: What we call certain things really matters. Why 1619 verses 1776? The framing, the approach we take mentally, leads us to tell new histories, which is exciting but daunting. As historians, we're always looking to ask new questions and those new questions then demand new answers. The joy of the research is looking for those new questions and arriving at new answers.

YHR: On the topic of the new, how have you settled into our historical moment?

EW: During Lunar New Year and I was talking to some friends who are all of Chinese ancestry, though from different places in China, Indonesia, some from the United States. As soon as COVID started to come from China I predicted that there would be racial consequences for Asians in the United States.

Racial ideas that connect Asian bodies to foreign threats and disease have longevity. These ideas have persisted in the United States since the mid 19th century, when Asians first arrived in large numbers. This suspicion lingers and then resurfaces when the political context is right. That, in some ways, affirmed what I know from studying—but then to see it unfold is awful.

As far as everything around Black Lives Matter and George Floyd, I'm really encouraged, at least among Asian Americans, that there is more conversation, more recognition, of the necessity for us as a country to tackle anti-Black racism. My sense is, from the conversations among Asian Americans, is that this is unusual in the amount of it that's been going on, the frequency, the level of interest, the surge, the attention. I’m hopeful in some ways. But I will qualify that. I'll give you a counterexample. I live in a college town, Bloomington, Indiana. There's been, over the past year especially, a lot of controversy about white supremacy, what that looks like, and how it manifests itself in our community. Last summer, it revolved around the presence neo Nazi vendors at our city-run farmers market.

Since then, debates about white supremacy have become much bigger and connected to everything that's been going on in the wake of the George Floyd murder. Clearly, there's a lot of resistance to or ignorance of the different forms of white supremacy that exist. On the one hand, I feel hopefulness, and on one hand, I feel quite anxious. People here think our town may be one of the next Charlottesvilles and if that happens, I won’t be surprised.

YHR: Your concerns tie to education, or, better said, the lack of it. The question of 1619 versus 1776 carries value in the K-12 classroom as well as the college campus. As we both know, this form of ignorance extends beyond Bloomington.

EW: Maybe not even ignorance so much as people feeling comfortable, and they don't really see why anything has to change. That is a hurdle, a big hurdle. It’s like, “oh we have this beautiful Saturday morning market, and while it’s unfortunately that there are sellers with neo Nazi ties, we need to preserve this market.” The activists in our town have made clear that them being there, as well as the beefed-up presence of law enforcement, makes people of color feel unsafe.

As far as the curriculum goes—that's really challenging. I’ll try to give you an example from my own teaching. I teach a course on US immigration history fairly regularly. Every time I teach it, which is about every other year, I make many changes. It's quite a lot of work because there's so much great new scholarship and also events unfolding in real time. In fact, this last fall when I taught it, the 1619 Project had just come out a couple weeks before, so I even tried to integrate some of the stuff in the magazine into my lessons. It's really hard to do all at once as an educator. You have your larger, overall goal of sharpening your teaching to reflect new findings and interpretations. But it’s difficult to tackle it all at once. Teaching courses like US history—it’s very challenging. There’s always going to be more than you can put that fits, so it's always a process of editing.

Figuring it out is hard, especially if you have the latitude to design your own syllabus or course. The problem of that, though—sometimes I feel like once you tug on something, the entire thing starts to unravel. I always appreciate people who publish roundups of new scholarship, whether they’re book reviews or even essays. I was recently looking at new literature that integrates Native American history and immigration history, something I'd like to do better, for instance. Some of it is just about figuring out where you can look for a little bit of the Cliff Notes version to point you in the right direction and then thinking about how you might find some specific ways to start implementing those changes in your curriculum.

YHR: Editing never ends, especially in our age of information. How do you revise your syllabi to reflect the ever-evolving research landscape online and in the archives?

EW: Less is more. This amazing buffet of information tempts us. Like you said, the buffet has expanded with technological innovations. But I've learned this, many times the hard way, that it's okay to have less. I always want to stuff more onto my plate, to continue the metaphor. But it can become overwhelming. I think with writing too, we as historians are so proud of all the sources we find, we want to put it all in there. So it's very painful sometimes to prune it. It’s really a craft, in terms of mastering what telling detail we can leave in, and when do we pull back and focus a bit on the broader strokes. You can't just throw the whole kitchen sink in there. Limitations of space, attention, your hard drive, your word counts, will be there. But it’s not all bad—it can be useful.

YHR: The Color of Success covered up to the 1960s. Will you continue this narrative in your upcoming book project?

EW: The project I'm focusing on right now is essentially a sequel, but it’ll look very different. I call it Overrepresentedbecause the question I began with: where did the concept of “underrepresented minorities” come from? Whenever I see that, I think that must mean people of color, except Asians. I always wondered how that came about and the logic of it. I open that up into a history of race, since the 1950s and 60s through now, with Asian Americans at the center. I trace a larger history of the changing racial order, racial politics, and democracy.

2020 is an important punctuation mark in that story. It will be challenging to write about the present and use digital sources. I've been working on how to use, for instance, social media as a primary source, which involves a whole other skill set that I’m developing thanks to the terrific Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities at Indiana University. I’m trying to figure out how I can incorporate that at some level, but also knowing my own limitations as a scholar.

YHR: You mentioned some recent scholarship you have been reading. Is there anything else that you are, watching or listening to that you have found particularly helpful or enjoyable?

EW: I've been binge watching Homeland. Political intrigue! Spycraft! Gaslighting! What stands out to me is how the show wants it both ways in terms of Islamophobia. In addition, I listen to different podcasts. I still love This American Life, because I went to graduate school in Chicago, where The American Life originated (WBEZ). When I watch TV or listen to podcasts I take mental notes on the storytelling. Something I thought less about when I was in graduate school was the writing part because we were so focused on the research and the argument.

Now I’m trying to focus much more on the narrative side of history. I have a friend who's a screenwriter, filmmaker. He had taught me that characters have to want something. I've been thinking a lot about that—how do you structure a chapter of a story, what drives the actors, and how do you tell the story and break it up in installments? I try to think about how a movie, a TV show, or a podcast tells a good story.

I’ll just mention that I have a friend, disability justice activist Alice Wong, and she has a new book out called Disability Visibility. It's a collection of first-person stories from people with disabilities. Alice says if she were a desert island, she would bring along a historian, because she said people need a storyteller. I like to think that stories and storytelling are a fundamental part of human existence, that people need these stories to make sense of ourselves.