Written by Kenia Hale, SM '21

Edited by Fiona Benson, SY '22

Cover Art by Kiera Hale, ig: @kierahaleart

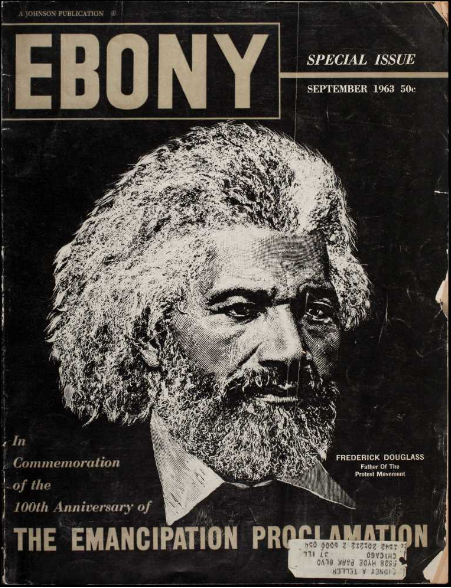

Since 1619, the story of enslaved, Black, forced migration has been ingrained in American history. From the Underground Railroad to the Great Migration, movement has been a key method to escape the clutches of white supremacy for descendants of enslaved Africans. The migration of Black people across the U.S. is practically a birthright. To this canon, I want to examine three stories of the Black Odyssey genre set in the future – Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, Janelle Monae’s Dirty Computer emotion picture, and Lena Waithe’s Queen and Slim. All three documents follow this legacy of Black migration into the future, reimagining definitions of kin and found family. Illustrating how the movement of Black people shapes public spaces, these works assert the importance of this migration in imaging black futurities.

Dirty Computer

Monae’s Dirty Computer begins in a world scarily similar to our own, in which a voice-over dictates that, “They started calling us Computers…People began vanishing––and the Cleaning began. You were dirty if you looked different. You were dirty if you refused to live the way they dictated. You were dirty if you showed any form of opposition at all.” (Monae) In this dystopia, Monae’s character Jane 57821 has been captured in a kind of re-education camp, which forces her to call herself a “dirty computer” and begins to delete her memories in order to “clean” her. As the cleaning process begins, the viewer is introduced to the life from which she was stolen, in which she drove around with her other Black femme friends, hid others from robot police, and vogued the night away at futuristic queer desert parties. Her first music and video work, “Crazy Classic Life,” begins by flashing between the faces of party goers, while a voice over from a sermon plays:

You told us, “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men and women are created equal, and are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, among these life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”

Here, the “us” seems to point to the members of Monae’s party: queer, trans young people of color. The use of the statement “you told us” speaks to an inditement and accusation of broken promises from the state on the protection of the marginalized bodies––in referencing the Declaration of Independence, one of the founding documents of the US, she thereby claims the inherent value of her and her friends. She challenges the legitimacy of the very society that marginalizes them. In unison, the party-goers sing, “We don’t need another ruler – all of my friends are kings / I am not America’s nightmare – I am the American dream,” rejecting the attempts by their society to obscure them, asserting their own identity as their dream.

On an individual level, Monae considers her position throughout the album, but especially in the outro of “Crazy Classic Life,” in which she raps:

Handcuffed in a bandeau

White boy in his sandals

Police like a Rambo

Roll it up blow it up like a candle Sambo

Me and you was friends but to them we the opposite –

the same mistake I’m in jail you on top of shit,

you living life while I’m walking around mopping shit.

Tech kid backpack now you a college kid. All I wanted was to break the rules like you.

It is no secret that the racialization of one’s body impacts their abilities to move through public space. In this world, even as she parties, Monae’s position as a pansexual Black woman – a

“Dirty Computer”––lands her in handcuffs, brutalized by police, incarcerated, and working manual labor, whereas her “white boy” party-mate is “on top of shit,” allowed to climb the ladder of social society and become a “tech kid.” As the robot police invade the utopia they’ve created, wreaking havoc and arresting party-goers, it is understood that the simple congregation of these “Dirty Computers” upends the status quo, and thus, must be stopped.

In her next memory, set to the song “Screwed,” we watch Jane 57821 and her coalition run through a city to escape the robot-police. They run down subway escalators covered in graffiti, sleep on rooftops, and have a queer rave in the basement of an abandoned building. Here, engaging with she and her friends’ cynicism with the world, Monae sings “And I––I––I hear the sirens calling and the bombs are falling in the streets we’re all––SCREWED.” Interestingly enough, their reclamation of abandoned city spaces feels like an assertion of their hopes of a new future, despite the apparent nihilism of their words. The chorus continues:

You fucked the world up now, we'll fuck it all back down

Let’s get screwed

I, I don't care

We'll put water in your guns

We'll do it all for fun

Let's get, let's get screwed

Here, their nihilism is complicated. While still singing about being “screwed,” Monae is also playful, threatening to steal state power by “putting water in [their] guns” and “do it all for fun.” In a way, even the word “screwed” becomes playful, as is implies both her understanding of a doomed society and an invitation for a sexual encounter. For her, “let’s get screwed” is an invitation, a challenge, a proposition to the state.

By turning the state’s oppression into a futile spectacle that she and her friends will eventually “fuck … all back down,” she delegitimizes it, returning the power to herself and other marginalized communities.

Monae’s commitment to images of herself and her people in the future speak to her own form of speculative science fiction. On the genre, Walidah Imarisha writes, “Whenever we try to envision a world without war, without violence, without prisons, without capitalism, we are engaging in speculative fiction. All Organizing is science fiction” (3). Although she and her fellow “Dirty Computers” remain oppressed in her futuristic world, they also find spaces in the city to exist in their truest form, and they eventually escape the State-sanctioned reeducation camp towards the end of the film. Although the film is left open-ended, this ambiguity provides the trio with a new future currently unimaginable.

Parable of the Sower

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower takes place in a Robledo, CA, in a near future in which America has been wrecked by climate change. The book follows Lauren Olamina––a young Black woman––on an exodus across California in search of a new home after her community is burned and destroyed. As the genre of science fiction is often centered on the survival of individual white men, Butler provides us a model for collective survival and liberation, imagining a future for Black and Brown communities. The daughter of a pastor, Lauren, distinguishes herself from her father by insisting that the community around her prepare for what she views as a changed world. Lauren’s father confronts her for what he calls “scare-talk.” Butler writes, “’Do you think the world is coming to an end?’ Dad asked … What I thought was, ‘No, I think your world is coming to an end, and maybe you with it.’” (62) Lauren, disillusioned with her father’s teachings, discovers her own religion centered on the principle that “God is Change,” and thus that our communities must evolve if we have any hope of surviving a changing world. With this in mind, Lauren works to form a community named “Acorn,” functioning as a form of utopia. On the topic of Utopia, Angela Warfield writes:

The aporia both requires and is the activity, the movement, and the precipitation of affirming something not determined. It necessitates a timely response, or responsibility to the other. The aporia is responsibility itself, which is to say, the structure of openness, open to respond without having a predetermined understanding of how to do so, since any predetermination or limit on responsibility would mean reducing the aporia to mere presentable boundaries and distinctions. (Warfield 64)

This speaks to Lauren’s worldview––an immense love for her family, to the point that she insists they learn to protect themselves and prepare for the world to come. Although she’s uncertain about the future, she is intentional about the importance of preparedness, of leaning into a changing world. She compares her community’s attempts to deny their realities as “ignoring a fire in the living room because we’re all in the kitchen, and, besides, house fires are too scary to talk about.” (63) For Lauren, discussing the realities of their “house fire” is how she asserts her love for her community.

Lauren also recognizes that her position and racialization will affect the way in which she travels. Because rape and sexual violence are so prevalent in her world, she informs her friends that “I’m thinking of traveling as a man,” to which her friend responds “That will be safer for you … you’ll have to cut your hair, though” (171). She understands that her Blackness will never be fully obscured, but that between this it may be possible to obscure certain layers of her intersecting identities. Although Lauren must confine herself to these gender hierarchies––because “We believed two men and a woman would be more likely to survive than two women and a man” (212)––she also refuses to replicate these hierarchies in her new future. She recognizes the social position of her original traveling group––made up of herself, a white man, and another black woman––and while befriending another mixed couple, insists that because “Mixed couples catch hell out here … We’re natural allies” (212). Through her journey, she literally creates the future utopia she desires.

James Baldwin once said “I can’t afford despair … You can’t tell the children there’s no hope.” Here, he refers to his deposition that despair alone will take us nowhere. The passion that pushes Lauren towards preparedness and survival is a method of fighting against despair, as it refuses to comply with climate cynicism or nihilism while also insisting on taking action in response to a changing world. In the community that Lauren discovers on her exodus across the west, she befriends families and other vulnerable peoples, for whom despair is no option. They understand that pretend that the world––or rather, the world of her parents––is ending, and they intend to survive to see a new one. According to Angela Warfield, “Butler's discourse stresses the political and ethical activism that results from, and is perpetuated by, the aporia. Lauren affirms the future in spite of its undecidability; she gestures toward a utopia that is nowhere.” (Warfield 67) Although, or perhaps because, Lauren sees no model for her new imagined future, she and her community must create their own.

Queen and Slim

My last examination of Black mobility centers on Lena Waithe’s Queen and Slim, a film released on Thanksgiving of 2019. The plot follows the first date of a young Black couple nicknamed? Queen and Slim. Their first date is upended when a police stop gone wrong results in Slim killing the police officer after the officer shoots Queen. Immediately, the two go on the run.

The very nature of police violence necessitates controlling the existence of Black bodies in spaces in which they’re deemed “unacceptable,” a shared legacy of other carceral institutions throughout the history of the United States. According to Ciryl,

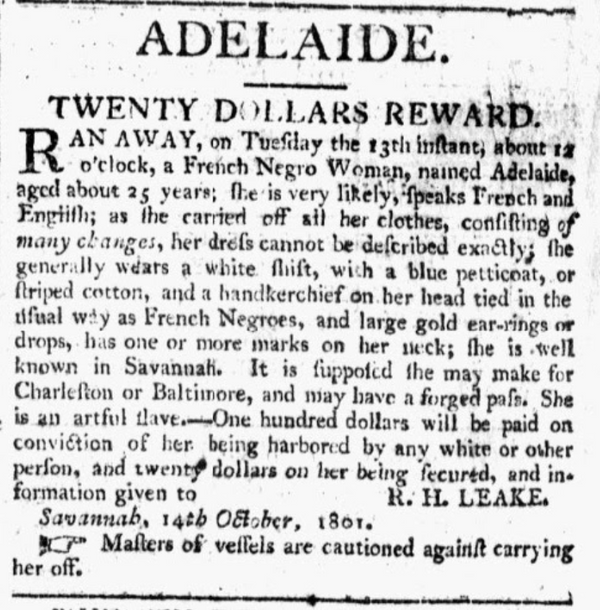

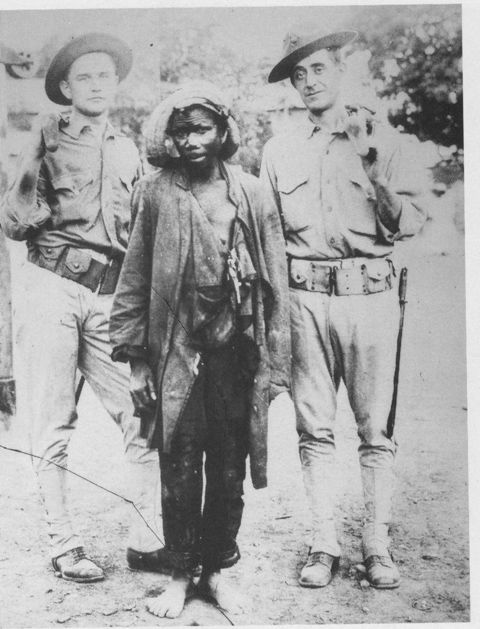

The monitoring of Black bodies is much older than either the current high-tech version or the original COINTELPRO. Browne notes that in eighteenth-century New York, “lantern laws” required that enslaved Black people be illuminated when walking at night unaccompanied by a white person. These laws, along with a system of passes that allowed Black people to come and go, Jim Crow laws that segregated Black bodies, and the lynching that repressed Black dissidence with murderous extrajudicial force, are all forms of monitoring that, as Claudia Garcia-Rojas observed in a 2016 interview with Browne for Truthout, have “made it possible for white people to identify, observe, and control the Black body in space, but also to create and maintain racial boundaries.” (Cyril 123)

Thus, because the control of Black movement is implicated throughout so much of American history, carceral violence and surveillance is often simultaneously a cause and effect of Black movement through space. Queen and Slim are simply another iteration in the legacy of state control of Black bodies.

After Slim proposes turning themselves in, Queen reminds him, “They’re trained to make you feel at ease. It’s their job to convince you everything will be okay. But the second you turn over your gun and confess you become property of the state. Is that what you want? You wanna be the state’s property?” (31) For the police state, the “safety” of public space is dependent on the control of Black people’s bodies. The pointed irony of this film is that the “safest” moments, the moments when our protagonists can let their guards down, are in the most Black-dominated spaces. For instance, when Slim and Queen buy food from Black children skateboarding in a parking lot, when they dance in an old Black-owned bar, or when they visit Queen’s Uncle’s house. In contrast, the scenes meant to inspire the most “safety” – their visit to the white couple’s house in particular, were moments viewers find themselves at the edges of their seats. While the Black communities they run into are undoubtedly on their side, the allegiance of the white couple is unclear, teetering between protecting the runaways and calling the police to “protect the wider public.” For Black people in cities, or anywhere, one’s positionality influences meanings of safety. Through their journey across America, the characters engage with a 21st century Green Book, mapping a new geography of Black safety connections through kinship and word of mouth.

Their Bonnie and Clyde-esque police chase––deeply reminiscent of a lynch mob –– is further complicated by the reception from others around them. The movie centers on the concept of collective memory and veneration, especially as contrasted to the actual intentions of the protagonists. Their first indication of their public perceptions is aided by the lens of a Black man named Get Low:

GET LOW

I support what y’all are doing.

QUEEN

What do you mean?

GET LOW

Killing these crooked ass cops. I

support that shit. We need to take

all these muthafuckas out.

SLIM

That’s not what we’re doing.

GET LOW

I saw the video. I watched that

shit like thirteen times. You shot

the fuck outta that muthafucka. He

deserved that shit.

While neither Queen nor Slim intended for their names to be associated with a movement, the nature of the public and surveillance takes their own story out of their control. Kevin Quashie considers this in his “The Trouble with Publicness: Toward a Theory of Black Quiet”: “Part of what hinders our capacity to see this quality [of silent resistance] in their gestures is a general concept of blackness that privileges public expressiveness and resistance. More specifically, black culture is mostly overidentified with an idea of expressiveness that is geared toward a social audience and that has a political aim; such expressiveness is the essence of black resistance.” (329) Because meaning is imposed on Black action in the public sphere often without the control of the actors, there is no space for Queen and Slim to control their role in this new found movement; even though they’ve been “quiet,” their actions have spoken for themselves in the eyes of the public. Their roles are have been decided for them, like actors in a performance they can’t escape. In contrast with Get Low, Queen and Slim encounter another Black father from the other end of the spectrum. He claims:

PLUMP BLACK MAN

It don’t matter if it was on

purpose or not. Now they really got

a license to kill us.

QUEEN

He shot me.

PLUMP BLACK MAN

You gave ‘em an excuse.

QUEEN

You weren’t there.

PLUMP BLACK MAN

No, I wasn’t. But I saw the affect

it had on my son. He thinks y’all

the second coming. Now every time

something happens he wanna make a

sign and go march in the streets. (84)

His own personal politics aside, the father’s claim “Now they really got license to kill us” speaks to the wider societal implications of the movement of Queen and Slim. Their actions, he claims, not only affect the polices’ treatment of them as individuals––their actions have led to hyper-vigilance on the side of the State against all Black folk. The mobility of a few Black people have ramifications on the State’s control of all.

Because of the long history of State control of Black mobility, the vision of Black mobility in the face of unjust state violence represents an embodied revolution, and the pair become a “quiet” spectacle. To this, activist Bronte Velez offers nuanced view of archival Black quiet:

Was everyone just erased? Or were some people actually intentionally evading the archive because what they were doing for their liberation couldn’t be written down? It needed to be remembered … [I want to] speculate on things that have not been written down and that I will not be able to find in anybody’s books. That [enslaved ancestors] were quiet and they can’t be told to me, they won’t come in this colonial way … but to trust that it’s in our bodies. (Velez)

Queen and Slim’s actions are remembered through their embodied revolution. The last scene of the movie shows their image on a mural in a predominantly Black neighborhood. Their actions have literally changed the city-scape around them, their memories remain in a public consciousness, a new commons. Here, the fact of their mobility implicates them into the macro scale of society. Their mobility lives on in public memory.

Each of these pieces provide a framework––a theory––on the future of Black movement and migration in America. Our cities are shaped for, and shaped by, legacies of movement and migration; these cities must change and evolve with a changing world. As climate migration and State violence necessitate further travel, it may become even more important to look towards these theories in order to craft more resilient cities and long-term communities.

Work Cited

Young, Ayana, and Brontë Velez. “Brontë Velez on Embodying the Revolution.” For The Wild, 15 Feb. 2018, forthewild.world/listen/bront-velez-on-embodying-the-revolution.

Butler, Octavia E. Parable of the Sower. New York: Warner Books, 1995. Print.

Warfield, Angela. “Reassessing the Utopian Novel: Octavia Butler, Jacques Derrida, and the Impossible Future of Utopia.” Obsidian III, 6/7, 2005, pp. 61–71. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44511662.

Waithe, Lena D. ‘QUEEN & SLIM’ 2018

Quashie, Kevin Everod. “The Trouble with Publicness: Toward a Theory of Black Quiet.” African American Review, vol. 43, no. 2/3, 2009, pp. 329–343. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41328610.

Cyril, Malkia. “Watching the Black Body.” Electronic Frontier Foundation, 26 Feb. 2019, www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/02/watching-black-body.

“James Baldwin: ‘I Can't Afford Despair.’” Colorlines, 18 Apr. 2015, www.colorlines.com/articles/video-james-baldwin-i-cant-afford-despair.

Monae, Janelle, director. Dirty Computer. YouTube, YouTube, 27 Apr. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdH2Sy-BlNE.