By Zarina Iman

Edited by Lizzie Bjork '21 and Zahra Yarali '24

Often mentioned in current popular culture, prenuptial agreements may seem a modern construction, but in fact, they have long existed in American society. Before and after the Revolutionary War, much of the American South operated under the English common law system. As such, Virginians in the antebellum period adopted marriage settlements, a form of prenuptial agreement originating in England as a workaround for coverture laws that prevented married women from attaining property. With these settlements, women could acquire “sole and separate” use of property, which, though guarded by a male trustee, was legally under their control. In much of the South, there was no organized approach to handling cases involving these settlements, so in Virginia, evidence of these contracts appears in the chancery court and legislative records. The chancery courts were courts of “equity” and thus, handled marriage settlement cases involving issues of property.1 The legislature and occasionally the courts also oversaw divorce cases, which often involved settlements. However, in 1827, overwhelmed by divorce petitions, the Virginia General Assembly granted chancery courts full authority over divorce cases, consolidating court power over marriage settlement law.2

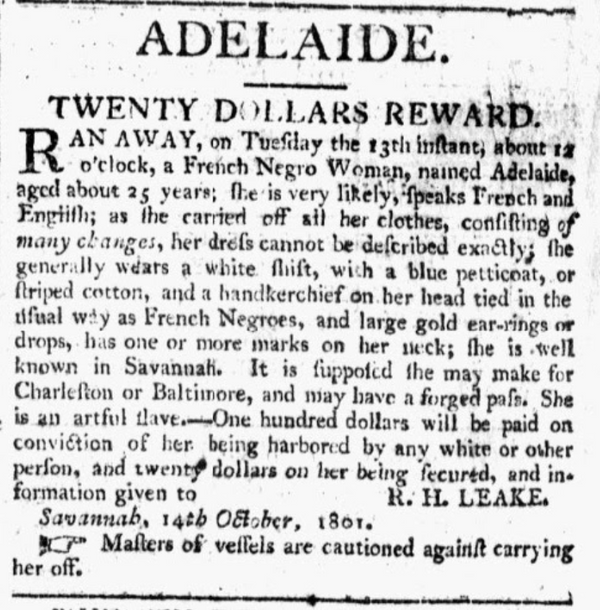

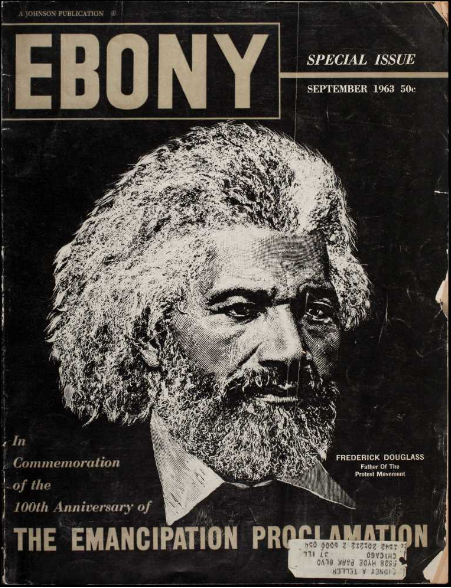

While social historians have recently turned their attention to cases of divorce and marital discord involving marriage settlements, the settlements themselves have long been neglected by researchers. In 1982, historian Marylynn Salmon authored one of the few, if not the only, studies of antebellum marriage settlements. Salmon’s article focused on a few thousand South Carolina settlements. The study revealed much about the lives of these women and the conditions of their marriages, but it also showed how settlements helped many of them buy and own slaves. Building upon these connections between marriage settlements, white women, and enslaved people, Stephanie Jones-Rogers briefly discussed marriage settlements in general in her book, They Were Her Property. However, aside from these works, marriage settlements are usually covered only in broader studies of antebellum divorce or finances, leaving much work to be done, especially regarding their relationship to white women’s slave ownership. Examining Virginia chancery court cases and the early legislative petitions involving marriage settlements, I have found that despite intervention and power grabs from their male relations, women used marriage settlements to assert dominance over their property holdings. Moreover, enslaved people had their life trajectories determined by these settlements and factored issues of ownership into their decisions.

Arranged by fathers — and occasionally other male relatives — skeptical of their son-in-law’s financial status and determined to ensure their grandchildren received their property holdings, marriage settlements were a way to protect a wife’s property from her husband’s debt. However, these contracts were not only invoked by male family members but also by women, especially widows, who knew to protect themselves and their property in later marriages. Records reflect that women openly asked partners for settlements before marriage. Women, more frequently than men, also leveraged marriage settlements in court to protect their property interests and, in the case of abusive husbands, themselves. These settlements and the court cases that arose from them were among the few ways for women to find legal protection and agency. Even then, these women faced male relatives, trustees, and others who tried to wrest control of their property. Still, many women exerted ownership over enslaved people, whom they actively bought and sold. While some formed bonds with their slaves, others blamed enslaved people for the deterioration of their marriages. Settlements and wills could grant enslaved people their freedom or upend their lives by forcing them to move and leave behind their lives. In their daily lives, enslaved people also likely experienced the dysfunction of households with marriage settlement disputes and had an awareness of who in the household owned them, informing their actions.

§§§

It is not clear when couples first began using marriage settlements in Virginia and the rest of the South, but by the early nineteenth century these contracts became popular, primarily serving as a safeguard of women's property from creditors.3 Chancery court records show that the subject of the first Virginia court cases involving marriage settlements were to invoke them against the claims of creditors. For example, in 1818, Elizabeth Latham, a Virginia woman, used her settlement to defend against her husband's creditors, who were suing her for a slave that her husband purchased on her behalf using funds she owned via a settlement.4 In an economy dominated by credit, the fortunes of even the wealthiest men in the antebellum South were never guaranteed. This became especially evident in the economic turmoil leading up to and during the Panic of 1837, after which came the first cohesive wave of married women’s property laws and rulings to protect women from their husband’s creditors.5 This legal action in the 1840s ensured women like Jane G. Jones, whose husband had purchased two slaves for her as repayment of his debt to her estate, could maintain their estate against their husbands’ creditors and potentially save their families from financial ruin.6 Both Jones and Latham, like dozens of other women, won injunctions against creditors, reflecting the legal power of their marriage settlements and their frequent use against creditors was acknowledged by Virginia courts.7

Eventually, the use of marriage settlements against creditors became so extensive that in 1856 the Virginia state legislature passed a law requiring deeds and similar documentation be notarized within sixty days of creation to be valid against the claims of creditors.8 The legislature did not pass laws directly regulating marriage settlements, probably because they expected chancery courts to address those questions, yet in this legislation, lawmakers explicitly referenced marriage settlements. This piece of legislation suggests that husbands may have backdated marriage settlements to protect property against creditors and that this maneuver became such a pervasive problem it had to be corrected en masse. As such, this legislation and the constant appearance of marriage settlements in cases with creditors indicate that a primary purpose of settlements was to protect women’s property from their husbands’ creditors.

The exact property that these settlements secured varied from woman to woman, though in Virginia many of these settlements included enslaved people. Anecdotally, historians have noted that slaves were often willed to women in lieu of other forms of property such as land.9 Research into Southern property-holding women more concretely suggests that a significant portion of women’s property in the South and in Virginia were indeed enslaved people. In a study of bankrupt women in the antebellum period, enslaved people, along with clothes and furniture, were listed among the key assets of these women.10 Bankrupt women were, of course, a small sample size, especially considering that most women could not own property at the time. However, Salmon, who noted in South Carolina most property covered under marriage settlements was enslaved people, supports the implications of this study with her own research.11 Furthermore, Catherine McDevitt’s examination of women’s wealth and property from 1780 to 1860 in Henrico County, Virginia, showed that seventy-two percent of women’s wealth was composed of slaves and only twenty percent in physical assets, like land.12 These findings imply that among Virginia’s property owning women, many of whom were only able to own property because of marriage settlements, slave-ownership was common, though maybe not as high as the rates in Henrico County. In essence, marriage settlements were inextricably linked to some form of slave ownership.

§§§

Despite being created in a woman’s name, chancery court records reveal that marriage settlements and the trusts they created were often handled by men with little oversight from women. Caroline M. Bowden’s 1844 suit to transfer the trusteeship of her estate, composed of thirty-eight slaves and land, from her brother to her husband is a prime example of this phenomenon.13 Bowden, who attained control of her estate through a marriage settlement, was the only person authorized to transfer trusteeship. Nevertheless, throughout the case records Bowden’s own words rarely appeared; instead, her husband who had joined the suit made the case for the transfer. The legal battle was largely one between Bowden’s husband and brother over her considerable estate. Trusteeship was not true ownership, but both men likely believed that they could convince Bowden to act in accordance with their own wishes. If both men believed they could obtain Bowden’s permission on whatever transactions they proposed, her estate could function as an extra source of money for either man to draw from that was simultaneously protected from creditors. Moreover, Bowden’s brother may have seen himself as a protector of the family’s property against Bowden’s husband. When Bowden did finally make her feelings known, she did so in a curt one-page letter, writing that “if you were to sell the property and pay me over the proceeds, I would immediately give those to my husband.”14 Bowden may have been genuinely uninterested in her estate, yet her husband’s intervention in the case could signify that he forced her to cede the trusteeship. Regardless, it seems the only reason Bowden was involved in the suit at all is because her marriage settlement designated her as the only one in control of the property.

The circumstances of Mary Burrell Wormeley Carter, who filed a joint suit with her husband against her mother and brothers in 1814, resembles those of Bowden, suggesting that such male domination over marriage settlement cases was not an isolated occurrence. Carter, with her husband, alleged that he was pressured into the contract and that it was “unfair” to him because upon Carter’s death, her family, rather than he, would inherit her property of 450 acres of land and seventeen enslaved people. Notably, Carter’s mother, Mary Wormeley, became trustee of Carter’s estate under the marriage settlement, and Carter’s husband accused her family of creating the contract “more with a view to the interest of Mrs. Wormeley and her sons than her daughter.”15 Despite Mrs. Wormeley playing a larger role in the settlement than most mothers would have, the case documents hold little record of what Mrs. Wormeley or her daughter thought of the situation. Again, the suit seems to have been instigated by the woman’s husband, not the woman herself, and litigated by the men around her.

Admittedly, Mary’s mother’s trusteeship is an aberration among the cases examined, though that Mary’s father is not the trustee makes it likely that Mrs. Wormeley was a widow and thus a femme sole, or someone who could hold property. Given the early date of the case, it is also probable that Virginia chancery courts had not yet set a precedent of male-only trusteeship. Why Mrs. Wormeley became the trustee and not one of Carter’s brothers is unclear; perhaps, she was yet another widow who knew all too well the importance of safeguarding property from her sons’ and son-in-law’s creditors. Still, the vilification of Mrs. Wormeley by her son-in-law and the court’s subsequent ruling against her trusteeship likely signals the general disapproval of female trusteeship men of the era held.16

The suits of Bowden and Carter are overt examples of how marriage settlements did not necessarily result in more female control, but oftentimes men’s involvement and intervention in settlements played out far less dramatically in the courts. In 1844, the same year Bowden’s suit was initiated, Lucy Ann Leber, a widow, asked the court to grant trusteeship to her new husband, after her prior trustee died. Within the same month, the court granted the transfer.17 By making her husband the trustee instead of an objective third party, Leber essentially gave him control of her assets. Leber’s suit seems unforced compared to Bowden and Carter because her new husband did not appear in the case in any significant way. Still, with her husband as the guardian of her property, Leber’s position was equal to that of Bowden and Carter. These women’s cession of partial or full control of their estates to men close to them reinforce the trend that despite being the legal owner, women could be and often were almost entirely separated from matters of their estates by male interventionists. Still, when women chose to, they could use settlements to exercise control over their property, which they often did in dire circumstances.

In many cases, marriage settlements and the women who held them were a means to the end of passing on property. Women’s families usually drafted these contracts to ensure property remained in the family while tangentially supporting these women. This strong need to preserve assets and control property is most apparent in suits like Gregory's Administrators v. Mark's Administrators from 1823. This suit, which eventually reached the Virginia Supreme Court, was between the second and third husbands of a woman who had died.18 That these men were fighting over their wife’s marriage settlements and property, even as she was not remotely present, demonstrates how removed women could be from these settlements. In fact, litigation over deceased women’s marriage settlements was common, as many children, mostly sons, brought suit against others to retain property covered by their mothers’ marriage settlements.19

§§§

In spite of men’s attempts to seize power, women still had legal control over their property via these settlements and many exercised it in proceedings.20 Though some settlements predetermined who received property upon a woman’s death, many gave women the ability to write wills, a power that doubtlessly influenced how family members interacted with women who held settlements and bolstered these women’s power, even in death.21 Simultaneously, women also employed settlements and the legal system to exert control over their property. In 1851, Anna T. Cocke, whose marriage settlement previously prevented her husband’s creditors from seizing her property, filed another suit, this time against her trustee. Cocke, who had become a widow since the first suit in 1843, sought to sell one of about fifteen slaves, Robert, to purchase a home for her and her children. However, Cocke’s trustee refused, and in response, she leveraged her marriage settlement in court, and the court affirmed her request. Required to follow Cocke’s demands, the trustee sold a slave upon Cocke’s request, though he sold a woman named Susan rather than Robert, who was hired out at the time. Reporting to the court, the trustee wrote that with the money from the sale he purchased a house for Cocke and her family.22 Cocke made her marriage settlement and her trustee work for her, and she was not alone.

In 1853, Mary P. Robinson, a widow, too found herself in court but with her son’s male guardians. The point at issue was whether the proceeds from the sale of an enslaved woman, Fanny, belonged to her or her young son.23 Before becoming a widow, Robinson and her husband formed a marriage settlement, under which they later sold Fanny and saved the proceeds. Understanding that she could use the money to support herself and her child, Robinson, like Cocke, attempted to draw upon the funds.When challenged, she successfully asserted her rights by taking her marriage agreement to court. Interestingly, like Cocke’s suit, Robinson’s child was named as a defendant - even though she would likely use the money generated by the suit for him - because with her husband gone Robinson was technically arguing against her children’s property claims. In spite of these, “competing” claims, both women successfully used the courts to exercise authority over their marriage settlements and property.24

In addition to using the courts to obtain power, many women attempted to secure their property before filing suits by asking their potential spouses to sign a marriage settlement. Salmon observes that women often had the most leverage right before a marriage, when their fiancés were eager to marry them.25 Many exploited that dynamic to settle their financial affairs, especially women who had previously been married, probably because they had either gained more property from prior marriages, realized the importance of maintaining their property through experience, or both. Adelia O. Turner represents this practice. Turner, who inherited two slaves from a prior marriage, asked her then future husband, John Turner, for a settlement. She told the court in 1837 that asking for a settlement was “not from any distrust at the time of the said John S. Turner’s proper affection for her,” but rather because Turner was “proposed of no property whatever.”26 The settlement that bequeathed her estate to her son by her previous marriage was likely a way to ensure that his claim on her property was not superseded by John’s or that of his potential creditors. Likewise, in 1824, Elizabeth Long Oliver recounted to the chancery court how she planned to ask her fiancé for a marriage settlement because he had three children from a prior marriage and was “in very embarrassed circumstances,” but he actually suggested it first.27 While Oliver did not actually have to ask for a marriage settlement, the fact that she intended to ask and recognized that it would be prudent to have one signifies how women knew the value of settlements and used them to their advantage. In addition to these uses, marriage settlements had a final application for women: protecting property in the face of marital discord. In fact, Turner and Oliver went to chancery courts and cited their marriage settlements because their marriages deteriorated to a point where legal intervention was necessary.28

§§§

When faced with abusive husbands and turbulent marriages, women relied on their marriage settlements to emphasize their separate property holdings and strengthen their claims of spousal support. Elizabeth Oliver filed a suit for an injunction and restraining order against her husband in 1822. Oliver’s husband abused her, “turned her out of doors penniless,” and usurped control of her large estate, which included about seven enslaved people.29 Oliver even recounted how shortly after their marriage, her husband attempted to tear up their marriage settlement, demonstrating he understood the legal power such a settlement held and likely expected her to leverage it in court.30 Moreover, his impulse to destroy the settlement so soon after the marriage suggests that he had planned to seize control of her property. Oliver did not live to see the conclusion of the case in 1832, but the administrator of her estate was granted full control of the property Oliver’s husband had attempted to take.31 This conclusion was of little practical use to the deceased Oliver, but her suit and the court’s affirmation of the suit proves that Virginian women could successfully apply their marriage settlements in a legal context to protect their holdings.

Like Oliver, Adelia O. Turner too sued for divorce and the protection of her property, invoking her 1832 marriage settlement against her husband to that end. Turner, who had lived apart from her husband after he, in the words of her petition, “bruised her body” like “a monster” and “slandered her character” to “respectable society,” had built her own business to sustain herself.32 Turner through “her own labor” ran a grocery and a “house of private entertainment” until her husband went into debt to a friend, who in turn seized her business as repayment. Alleging that her husband and his friend contrived the plan to break up her business, Turner sought and received an injunction against the sale of her business, which was built with assets from her estate.33 Though the court did not address whether the debt was a scheme plotted by her husband, it recognized Turner’s labor and the protection to which her settlement entitled her, and unlike Oliver, she lived to benefit from the ruling.

While incidents of physical abuse often prompted women to go to court, women also initiated legal proceedings for a variety of other non-physical reasons. For example, in an 1840 legislative petition for divorce and restoration of property, Mary Lawson alleged that her husband was emotionally abusive and bullied her into signing the property in her marriage settlement over to him.34 Lawson likely turned to the legislature for clarity, since her husband had filed a claim against her in Amelia County Chancery Court for slander, and she too had a suit against him in Hanover County. Only half an hour after their marriage, Lawson claimed in her petition, her husband began inquiring about her property, specifically her “servants” or enslaved people. He then remained distant, only berating Lawson when they spoke, which she recalled “wound[ed] most painfully my feelings.” Desperate, Lawson finally agreed to sign over her slaves and property to her husband and his descendants in exchange for a separation.35 Throughout her unpleasant marriage, Lawson reported no physical abuse, but the legislature recognized the duress she was under and referred her case to an Assembly subcommittee.36 The record does not reflect the final result of Lawson’s case, but the legislature did not dismiss her claims outright. Instead, they met with her to hear her petition, signaling that claims of emotional distress alone held weight in their eyes.37

Lawson’s petition was not only unusual for its claims of emotional abuse but also for its outright accusation that when marrying her, Lawson’s husband was “more influenced by regard for [her] property than for [her] self.”38 Lawson was the only woman of the records examined to directly discuss the phenomenon, but men marrying women for their property was a frequent theme in these cases of marital discord. Elizabeth Oliver’s husband's behavior, for instance, mirrors that of Lawson’s husband, though he did not openly pursue her property as quickly.39 It is impossible to know for certain why men agreed to marriage settlements they then attempted to evade, but perhaps, they believed they could sway their new brides to hand over their estates. Legal records reflect that many women would not surrender their power so easily.

Aside from fortifying their property claims against their husbands, women took their marriage settlements to court to negotiate for alimony and general compensation. Many suits for divorce or separation had underlying requests for compensation. However, some cases were about spousal support alone, like that of Nancy Holland in 1849. Prior to their marriage, Holland’s husband signed a marriage settlement in which he agreed to place five slaves of his in a trust for her.40 Holland’s husband fulfilled his promise, but following the couple’s informal separation, she learned that he had gifted some of the slaves in her trust to his grandchildren. Holland, as a result, could not support herself and asked that the court require her husband to give her more money, which he agreed to do. Resolved within the same month, this case was not as dramatic as some. Holland did not challenge her husband giving her property to his descendants, and he did not challenge her request for more money.41 The straightforwardness of this case might possibly be because Holland accepted that her property was originally her husbands and both parties were older and recognized they did not need as much money for upkeep as their children and grandchildren did. Nevertheless, this suit displays how women used their settlements to obtain alimony at the most basic level.

In a far more convoluted case, spanning from about 1820 to 1848, Peggy Betty Graham too tried to receive compensation from her husband for violation of their marriage. Graham’s original petition explained that her husband had been cohabiting with another woman, Ann Payne, and had conveyed to this woman much of the couple’s slaves and land, some of which were “promised” to Graham as her own property, exclusive of her husband’s debts. In 1820, Graham won $1660 in court from her husband for his breach of their marriage settlement.42 However, Graham’s husband declared himself insolvent because Payne held much of his property. Graham charged her husband and Payne with intentionally “defrauding” her, and what ensued was decades of Graham attempting to recover her wealth.43 Through multiple letters and petitions to the court, Graham estimated the worth of the property her husband had given away and cited when her husband and Payne had sold land or specific enslaved people off at a significant deficit that could have been used to settle her claim. Although helped by a lawyer or someone of a legal background, the specificity of Graham’s claims reveal that she was intensely involved in managing her property, showing the extent women could be immersed in matters of their estate. Graham also kept track of her still-husband and Payne, writing to the court when the pair had moved out of state in 1824, and amending her suit to include Payne’s new husband in 1825.44 Her determination in pursuing this case and her multiple petitions to the court further show how women took advantage of the possible legal recourse available to them.

§§§

Despite being a source of legal authority for white women, marriage settlements did not make these women all powerful. Women often faced pushback from their trustees and the male dominated courts. When attempting to sell her slave Robert, Anna Cocke had to take her trustee to court and in court, presented an affidavit from a man who agreed that her decision to sell Robert was sound. Only then did the trustee agree to the sale, though as previously discussed, documentation shows he still sold off another enslaved person instead.45 Like Cocke, Frances Price had to ask the local court to confirm that her selling of Peter, eight, and Sally, ten, was within her power because her trustee had challenged the decision.46 The outcome of the case is unclear, but this was not the first time Price had problems with her trustee. She in fact tried to remove him eight years prior in 1850, and he in turn scolded her in a letter, proclaiming that he had long acted like her “father” and questioned if “evil… repelled gratitude from [her] heart.”47 His patronizing tone is emblematic of the rigid patriarchal standards women operated under, marriage settlement or no. Price’s later case and Cocke’s also reflect the threat trustees posed to women’s financial power. This threat is most evident in the 1855 case of Meriel Colley, a widow whose trustee owned a local store and knowingly allowed her to accumulate a massive debt in his store, before suing her for her assets. The Special Court of Appeals ruled against the trustee, noting that he violated his duties as a trustee. His actions reinforce the fact that trustees could and did undermine the authority of women and their marriage settlements.48

While a path to power for women, courts too could limit women’s control over their property. Peggy Betty Graham, who, as explained earlier, lost the majority of her assets to her husband, is just one of the many women who had their claims dismissed by the courts.49 In 1866, Elizabeth Bailey, whose settlement allowed for her husband to use but not own the slaves and land she brought into the marriage, petitioned that her husband, who left her in 1861, relinquish any rights to her land. Bailey, who was especially hard pressed for money because her slaves became free post-emancipation, had her suit dismissed by the courts because her husband was willing to reunite with her.50 Bailey’s case, like Graham’s, reflects how the courts curtailed women’s property rights. Moreover, the court’s reasoning in Bailey’s case suggests that courts sought to preserve women’s status as wives, dependent on men. In fact, Virginia courts were reluctant to grant outright divorces even when they did uphold women’s control over their assets.51 Thus, women like Adelia O. Turner, who offered detailed accounts of her husband’s physical abuse, could usually only hope to be legally separated from their husbands, in spite of the economic independence granted to them via settlements.52

§§§

Any uncertainties caused by overbearing trustees or unsympathetic courts did not stop these women from using their settlements to exercise full authority of their property, including their enslaved people. In most cases, women’s relationship to enslaved people was one of impersonal ownership. Women like Mary Robinson and Peggy Betty Graham expressed an understanding of their property by estimating the value of their slaves in their suits.53 Anna Cocke and Frances Price also openly discussed the profitability of different enslaved people, like Price’s Peter and Sally, who she believed were too young to be “profitable” or Cocke’s Robert, who she found “impudent” and thus a bad investment.54 However, not all women were as engaged with their responsibilities as slave owners. Anne H. Lee, the widowed mother of General Robert E. Lee, petitioned to sell slaves she inherited via her deceased sister’s marriage settlement because she found hiring them out to be “disagreeable” and did not want to worry about their “elopement.”55 §§§

Additionally, though these cases were primarily about finances, there are hints, like who these women freed in their wills, that they could have personal bonds with enslaved people. In her 1843 case, Cocke even explained that she did not want creditors to seize her slaves because she had an “attachment” to some of them, indicating some sort of amiable feeling beyond unfeeling ownership.56 Nevertheless, not all relationships between white women and enslaved people in Virginia’s records were positive. Though not prominent in the records I examined, enslaved people could be at the heart of divorce cases, according to a study of legislative petitions by Glenda Riley. In these cases, mostly white women exposed their husbands’ sexual liaisons with slaves, portraying this miscegenation as an act of cruelty in itself. 57 One wife recounted to the court how she had to endure her husband’s “slave favorite” eating breakfast at her dining table.58 There is no exact count of how many of these cases involved marriage settlements, but these tense relationships were yet another way women interacted with those they owned.

§§§

When determining which enslaved people were affected by marriage settlements, it becomes clear that settlements had the potential to alter all enslaved peoples’ lives. Based on these cases, enslaved people in marriage settlements varied in age, gender, type of labor, and familial status, with some people listed with spouses or children. Despite these variations, marriage settlements affected enslaved people in two major ways: being a pathway to freedom or a source of movement and thus, separation. Sarah Greene’s 1784 petition demonstrates the first effect of settlements. Greene’s owner agreed to set her and her children free, but died before he could do so. His widow then agreed to honor the promise, asking her second husband to create a marriage settlement freeing Greene. While the husband declined, he agreed to draft a postnuptial agreement to set Greene free but had since died and before his death, left his wife in Ireland, where she was unable to help Greene.59 In her petition, Greene asked that the legislature confirm her and her children’s freedom because the second husband’s relatives took two of her children to “Carolina” and planned to take Greene and her other two soon. Greene’s petition, which the legislature tabled, does not contain any copy of the settlement mentioned, likely because she did not have access to it.60 Her plight represents how deeply connected the freedom of enslaved people could be to marriage settlements, for if her widowed owner had created one sooner, Greene and her children’s freedom would have been in far less jeopardy.

Beyond potentially providing freedom, marriage settlements could conversely contribute to separation and movement, uprooting enslaved people. As with male owners, the enslaved people of women could be hired out, like Ned who belonged to Francis Price, or sold, like the enslaved people of Anne H. Lee.61 Moreover, by enabling women to write wills, marriage settlements facilitated further separation, as women divided their property, among which was enslaved families, and passed these people on to new and often different owners, severing enslaved people’s ties.

However, women could also free enslaved people in their wills, highlighting the dual meaning that settlements and the wills borne out of them could have for enslaved people. The case that probably best demonstrates both settlements’ capacity to provide freedom and disrupt lives is that of the second husband of the deceased Rebecca N. Mathews. Her marriage settlement allowed her to own over thirty enslaved people during her marriage, and in her will, she ordered five of those people to be freed. However, this freedom was conditional; Mathews stipulated that if she had debts, those five people would have to be hired out for an extra period of time to help pay off the debt, along with her other slaves, who were to be sold.62 Court documents reveal that Mathews did indeed accrue thousands of dollars of debt, so after her death, her husband sold her slaves to about a dozen different owners, doubtlessly severing the familial bonds of some of Mathews’ enslaved people. The five who were supposed to gain their freedom were also hired out for a yearlong term, though their buyers had to pay a bond to ensure that they would be treated well and freed.63 The eventual fate of Mathews’ slaves is unknown, but her marriage settlement is representative of how settlements impacted the lives of the enslaved by moving and separating them, and, as in the case of the five, providing some avenue to freedom.

§§§

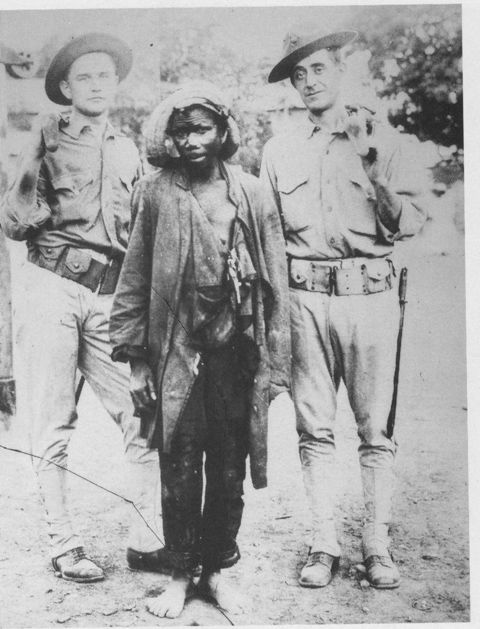

Without the ability to testify in court, enslaved people’s experiences with marriage settlements are absent from the record. However, Odom v. Odom, an 1867 case from Georgia provides some insight into what enslaved people may have undergone. The case includes the testimony about the Odom household from the Odoms’ former slaves, who could testify because of emancipation. Harriet Odom, who owned forty-two enslaved people under her settlement, sued her husband for divorce, alleging he physically abused her and fathered an enslaved child.64 The Odoms’ formerly enslaved people corroborated her claims. Ben Bryan told the court that Odom’s husband had a child with his slave Hester, who “had to obey his call” because she was his property, not his wife’s. Another former slave, Louisa, a “house-girl,” experienced this abuse first-hand, testifying that Odom’s husband offered her money to grope her and made advances when Odom was away. Described as having “lived with Mrs. Odom,” Louisa likely could resist Odom’s husband because she probably belonged to Odom, unlike Hester.65 While these narratives convey the pervasive sexual abuse and domestic turbulence some enslaved people endured in households with strained marriages, the contrast between Louisa’s and Hester’s experiences and Bryan’s acknowledgement of Hester’s owner also show that enslaved people understood the division of assets outlined by marriage settlements and factored them into daily decisions.

Adeline Odom and Rose Haughbook, formerly enslaved women who had been with Odom for years, recalled how her husband pushed her and even threw urine on her. Notably, this physical abuse extended to the enslaved people, who recalled being shoved and incidents, like the brutal whipping of a woman named Becky.66 Again, this testimony highlights the abuse and instability enslaved people likely saw and underwent in dysfunctional households. Moreover, these women’s detailed testimony against a white man, certainly more powerful than them, and their documented connection to Odom suggests they felt shielded by her ownership, or possibly even obliged to testify. In contrast to Adeline and Haughbrook, at least one formerly enslaved person refused to testify and in doing so was jailed, reinforcing that not all enslaved people felt positioned to speak against their current or former masters.67 As historian Loren Schweninger explains, enslaved people often struggled to pick the “right side” in times of marital discord.68 For many of the formerly enslaved witnesses, Harriet Odom was the right side, likely because they were aware of the power her settlement and ownership gave her and possibly because she, as some remembered, would occasionally intervene when her husband abused them. Regardless of their exact motivations, these witnesses establish that enslaved people faced physical and sexual abuse and witnessed much of their owners’ marital turbulence firsthand in households where settlements and marriages themselves were under dispute. Further, these testimonies show that enslaved people probably knew who exactly owned them and acted accordingly. Of course, Georgia is not Virginia and this case cannot represent all cases. Nevertheless, Odom provides the rare opportunity to hear enslaved people directly, and their words taken with the experiences of enslaved people in Virginia, like Sarah Greene, Robert, and more, provide some insight into enslaved people’s lives in relation to marriage settlements.

§§§

Originally a common law invention devised by men to ensure their property stayed within the family even when they had daughters, these antebellum Virginia marriage settlements ultimately became a source of legal power for white women. Despite the intervention of domineering husbands, women leveraged settlements to write wills, assert ownership against the competing claims of their husbands, creditors, and others, and sue for relief from deteriorating marriages. Still, meddling trustees and unsympathetic courts checked women’s power, though many women remained engaged in the management of their property, including slaves. Beyond ownership, records indicate that white women could also have complicated relationships with their enslaved property, forming bonds with them or blaming them for marital disputes.

For enslaved people, marriage settlements could be the key to their freedom or another source of separation from loved ones. Further, in households with marriage settlements, enslaved people likely knew who owned them and conducted themselves accordingly. In homes with strained marriages, enslaved people witnessed and could be caught up in abuse between couples. Though white women and enslaved people could be co-victims of abuse, marriage settlements made white women active participants and benefactors of slavery. Thus, as settlements were a source of power for Virginia’s white women, they facilitated the subjugation of enslaved people.

Bibliography

Adelia O. Turner Petition. Aug. 28, 1837 to May 31, 1838. Folder 016453-006-0166. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864). ProQuest History Vault.

Anna F. Cocke v. Thomas Y. Tabb etc., 1853-010. Chancery Causes: Petersburg City, 1853. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=730-1853-010.

Anne H. Lee: Petition. Charles City County, Dec. 12, 1816. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Legislative Petitions Digital Collection. http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:1801/webclient/DeliveryManager?application=DIGITOOL3&owner=resourcediscovery&custom_att_2=simple_viewer&pid=3067315.

Censer, Jane Turner. "'Smiling Through Her Tears": Ante-Bellum Southern Women and Divorce." The American Journal of Legal History 25, no. 1 (1981): 24-47. doi:10.2307/844996.

Chused, Richard H. "Married Women's Property Law: 1800-1850." Georgetown Law Journal 71, no. 5 (June 1983): 1359-1426. https://heinonline-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/glj71&i=1375.

Doswell v. Anderson, 1855 Va. LEXIS 78, 1 Patton & H. 185 (Supreme Court of Virginia;Special Court of Appeals January, 1855). https://advance-lexis-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/api/permalink/58a143de-48fa-4ff3-b6c3-2c7922bdade2/?context=1516831.

Elizabeth A. Bailey Petition. Mar. 5, 1866 to Oct. 4, 1866. Folder 016453-011-0882. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864). ProQuest History Vault.

Elizabeth Long Petition. Sep. 5, 1825 to Jun. 6, 1832. Folder 016453-003-0911. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864). ProQuest History Vault.

Fleet William Cox, Guardian v. Mary P. Robinson Etc., 1853-015. Chancery Causes: Westmoreland County, 1853. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=193-1853-015.

Francis E. Price By etc. v. Joseph B. Whitehead GDN, 1854-001. Chancery Causes: Isle of Wight County, 1854. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=093-1854-001.

Francis E. Price Petition. Feb. 11, 1858 to , May 16, 1859. Folder 016453-011-0036. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864). ProQuest History Vault.

George Washington Carter and Mary B. Wormeley Carter Petition. Mar. 12, 1813 to Jul. 31, 1814. Folder 016453-002-0542. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864). ProQuest History Vault.

Gregory's Adm'r v. Marks's Adm'r, 22 Va. 355, 1823 Va. LEXIS 16, 1 Rand. 355 (Supreme Court of Virginia March 17, 1823). https://advance-lexis-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/api/permalink/1a5a951f-8fdf-462d-be90-77e39ab95e45/?context=1516831.

Gross, Karen, Marie Stefanini Newman, and Denise Campbell. "Ladies in Red: Learning from America's First Female Bankrupts." The American Journal of Legal History 40, no. 1 (1996): 1-40. doi:10.2307/845460.

Harrison E. Cocke etc. v. William Friend etc, 1844-029. Chancery Causes: Petersburg City, 1844. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=730-1844-029.

James Z. Mathews. v. EXR of Rebecca N. Mathews Etc, 1854-038. Chancery Causes: Petersburg City, 1854. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=730-1854-038.

Matthews, James Muscoe, and Seth L. Rogers. Digest of the Laws of Virginia, of a Civil Nature and of a Permanent Character and General Operation: Illustrated by Judicial Decisions. To Which are Prefixed the Constitution of the United States, with Notes; and the New Bill of Rights, and Constitution of Virginia. Vol. 1. Richmond: J. W. Randolph, Printed by C. H. Wynne, 1856. The Making of Modern Law: Primary Sources. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DT0106901625/MMLP?u=biddle&sid=MMLP&xid=01d3f2c0.

Mary W. Lawson: Petition. Fairfax County, Jan. 8, 1840. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Legislative Petitions Digital Collection. http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:1801/webclient/DeliveryManager?application=DIGITOOL3&owner=resourcediscovery&custom_att_2=simple_viewer&pid=3101187.

McDevitt, Catherine. “Women, Real Estate, and Wealth in a Southern US County, 1780–1860.” Feminist Economics 16, no. 2 (2010), 47-71, doi: 10.1080/13545700903488161.

Nancy Holland by etc. v. John Holland, 1849-002. Chancery Causes: Fluvanna County, 1849. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=065-1849-002.

Peggy Betty Graham v. George George & Ann Payne, Ect., 1848-011. Chancery Causes: Scott County, 1848. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=169-1848-011.

“Petition 11684005; Virginia.” Race & Slavery Petitions Project, University of North Carolina Greensboro. Updated: May 20, 2009. https://library.uncg.edu/slavery/petitions/details.aspx?pid=2814.

“Petition 21681802; Virginia.” Race & Slavery Petitions Project. University of North Carolina Greensboro. Updated: May 20, 2009. https://library.uncg.edu/slavery/petitions/details.aspx?pid=15038.

“Petition 21684316; Virginia.” Race & Slavery Petitions Project. University of North Carolina Greensboro, Updated: May 20, 2009. http://library.uncg.edu/slavery/petitions/details.aspx?pid=12993.

“Petition 21684415; Virginia.” Race & Slavery Petitions Project. University of North Carolina Greensboro. Updated: Feb. 17, 2009. http://library.uncg.edu/slavery/petitions/details.aspx?pid=13026.

Odom v. Odom, 36 Ga. 286, 1867 Ga. LEXIS 41 (Supreme Court of Georgia June, 1867). https://advance-lexis-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/api/permalink/6c56bff0-df9a-471d-bda3-737c6101ee07/?context=1516831.

Riley, Glenda. "Legislative Divorce in Virginia, 1803-1850." Journal of the Early Republic 11, no. 1 (1991): 51-67. doi:10.2307/3123311.

Salmon, Marylynn. "Women and Property in South Carolina: The Evidence from Marriage Settlements, 1730 to 1830." The William and Mary Quarterly 39, no. 4 (1982): 655-85. doi:10.2307/1919007.

Sarah Greene: Petition. Fairfax County, Dec. 3, 1784. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Legislative Petitions Digital Collection. http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:1801/webclient/DeliveryManager?application=DIGITOOL-3&owner=resourcediscovery&custom_att_2=simple_viewer&pid=3070115.

Schweninger, Loren. Families in Crisis in the Old South: Divorce, Slavery, and the Law. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

William R. Bowden v. Thomas W. Gee Trst, ect., 1860-042. Chancery Causes: Petersburg City, 1860. Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia. Chancery Records Index. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=730-1860-042.

Endnotes

1. Richard H. Chused, "Married Women's Property Law: 1800-1850," Georgetown Law Journal 71, no. 5 (June 1983): 1364, 68.

2. Glenda Riley, "Legislative Divorce in Virginia, 1803-1850," Journal of the Early Republic 11, no. 1 (1991): 52.

3. Salmon, "Women and Property in South Carolina,” 655-58.

4. “Petition 21681802; Virginia” Race & Slavery Petitions Project, University of North Carolina Greensboro, Updated: May 20, 2009.

5. Chused, "Married Women's Property Law: 1800-1850," 41.

6. “Petition 21684316; Virginia” Race & Slavery Petitions Project, University of North Carolina Greensboro, Updated: May 20, 2009.

7. “Petition 21681802; Virginia” Race & Slavery Petitions Project.

8. James Muscoe Matthews and Seth L. Rogers, Digest of the Laws of Virginia, of a Civil Nature and of a Permanent Character and General Operation: Illustrated by Judicial Decisions. To Which are Prefixed the Constitution of the United States, with Notes; and the New Bill of Rights, and Constitution of Virginia, Vol. 1. Richmond: J. W. Randolph, Printed by C. H. Wynne, (1856): 560-62, The Making of Modern Law: Primary Sources.

9. Salmon, "Women and Property in South Carolina, 665.”

10. Karen Gross, Marie Stefanini Newman, and Denise Campbell, "Ladies in Red: Learning from America's First Female Bankrupts," The American Journal of Legal History 40, no. 1 (1996): 15.

11. Salmon, "Women and Property in South Carolina,” 665-667.

12. McDevitt, Catherine. “Women, Real Estate, and Wealth in a Southern US County, 1780–1860.” Feminist Economics 16, no. 2 (2010), 54.

13. William R. Bowden v. Thomas W. Gee Trust, ect., 1860-042, Chancery Causes: Petersburg City, 1860, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index.

14. William R. Bowden v. Thomas W. Gee Trust, ect., 1860-042.

15. George Washington Carter and Mary B. Wormeley Carter Petition, Mar. 12, 1813 to Jul. 31, 1814, Folder 016453-002-0542, Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864), ProQuest History Vault.

16. Id.

17. “Petition 21684415; Virginia,” Race & Slavery Petitions Project, University of North Carolina Greensboro, Updated: Feb. 17, 2009.

18. Gregory's Adm'r v. Marks's Adm'r, 22 Va. 355, 1823 Va. LEXIS 16, 1 Rand. 355 (Supreme Court of Virginia March 17, 1823).

19. Lawson Hathaway Jr.’s 1818 suit against his father for trying to sell enslaved people left for him by his mother (Petition 21681814) and Edward Hugh Caperton’s 1853 petition to sell enslaved people bequeathed to him by his mother’s settlement (Petition 21685309) are two examples of sons invoking mothers’ settlements after their death.

20. Women could not directly file suits in the chancery courts but had to go through a “next best friend,” oftentimes a man close to them or a lawyer. Still, the court petitions were written from the point of view of these women as they would explain the circumstances surrounding their suits.

21. Harrison E. Cocke etc. v. William Friend etc, 1844-029, Chancery Causes: Petersburg City, 1844, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index.

22. Id.

23. Fleet William Cox, Guardian v. Mary P. Robinson Etc, 1853-015, Chancery Causes: Westmoreland County, 1853, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index.

24. Id.

25. Salmon, "Women and Property in South Carolina,” 661.

26. Adelia O. Turner Petition, Aug. 28, 1837 to May 31, 1838, Folder 016453-006-0166, Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864), ProQuest History Vault.

27. Elizabeth Long Petition, Sep. 5, 1825 to Jun. 6, 1832, Folder 016453-003-0911, Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864), ProQuest History Vault.

28. Adelia O. Turner Petition.

29. Elizabeth Long Petition.

30. Id

31. Id.

32. Adelia O. Turner Petition.

33. Id.

34. Mary W. Lawson: Petition, Fairfax County, Jan. 8, 1840, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection.

35. Id.

36. “Petition 11684005; Virginia,” Race & Slavery Petitions Project, University of North Carolina Greensboro, Updated: May 20, 2009.

37. Mary W. Lawson: Petition.

38. Id.

39. Id.

40. Nancy Holland by etc. v. John Holland, 1849-002, Chancery Causes: Fluvanna County, 1849, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index.

41. Id.

42. Peggy Betty Graham v. George George & Ann Payne, Ect., 1848-011, Chancery Causes: Scott County, 1848, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index.

43. Id.

44. Id.

45. Anna F. Cocke v. Thomas Y. Tabb etc., 1853-010.

46. Francis E. Price Petition, Feb. 11, 1858 to May 16, 1859, Folder 016453-011-0036, Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864), ProQuest History Vault.

47. Francis E. Price By etc. v. Joseph B. Whitehead GDN, 1854-001, Chancery Causes: Isle of Wight County, 1854, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index.

48. Doswell v. Anderson, 1855 Va. LEXIS 78, 1 Patton & H. 185 (Supreme Court of Virginia; Special Court of Appeals January, 1855).

49. Peggy Betty Graham v. George George & Ann Payne, Ect., 1848-011.

50. Elizabeth A. Bailey Petition, Mar. 5, 1866 to Oct. 4, 1866, Folder 016453-011-0882, Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Series II: Petitions to Southern County Courts, Part C: Virginia (1775-1867) and Kentucky (1790-1864), ProQuest History Vault.

51. Jane Turner Censer, "'Smiling Through Her Tears": Ante-Bellum Southern Women and Divorce." The American Journal of Legal History 25, no. 1 (1981): 24.

52. Adelia O. Turner Petition.

53. Fleet William Cox, Guardian v. Mary P. Robinson Etc, 1853-015.

54. Anna F. Cocke v. Thomas Y. Tabb etc., 1853-010.

55. Anne H. Lee: Petition, Charles City County, Dec. 12, 1816, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection.

56. Harrison E. Cocke etc. v. William Friend etc.

57. Riley, "Legislative Divorce in Virginia, 1803-1850,” 55, 57-58.

58. Id.

59. Sarah Greene: Petition, Fairfax County, Dec. 3, 1784, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection.

60. Id.

61. Francis E. Price By etc. v. Joseph B. Whitehead GDN, 1854-001.

62. James Z. Mathews v. EXR of Rebecca N. Mathews Etc., 1854-038, Chancery Causes: Petersburg City, 1854, Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index.

63. Id.

64. Odom v. Odom, 36 Ga. 286, 1867 Ga. LEXIS 41 (Supreme Court of Georgia June, 1867).

65. Id.

66. Id.

67. Id.

68. Loren Schweninger, Families in Crisis in the Old South: Divorce, Slavery, and the Law. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 101.