Written by Lydia Burleson, JE 21'

Edited by Jisoo Choi, DC 22'

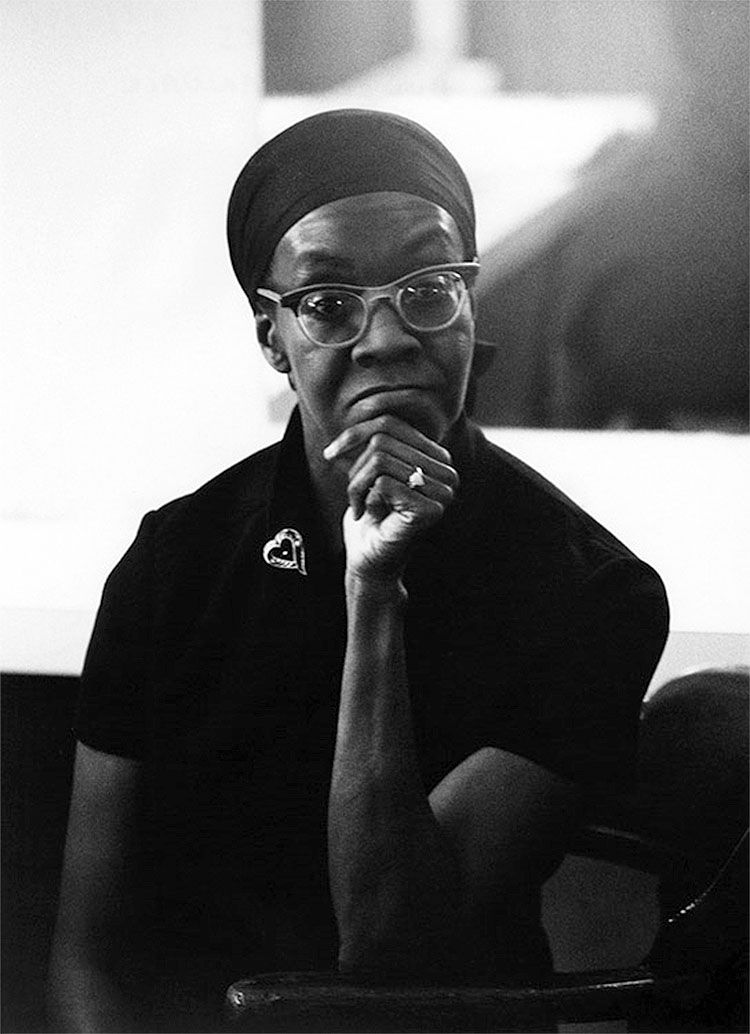

In the time before and during the Civil Rights Movement, Gwendolyn Brooks used her poetry to explore the shifting concept of Black agency, specifically the freedom of choice and movement for Black individuals within a white-dominated society. In her pre-Civil Rights Movement works like A Street in Bronzeville, Brooks focuses on the Black domestic, specifically on how her poetry’s depictions of Black-dominated spaces forces readers to “confront and resist gender, economic, and racial oppression” (Thorsson). With the Civil Rights Movement moving past the Black domestic to confront racial oppression in all facets of American society, Brooks, too, shifts from her localized poetry to interrogating interactions between Black and white Americans in public spaces. This change in Brooks’ poetic setting coincides with what critics like The New York Times have noted as a shift “in form and concern after [Brooks] attended a conference of Black writers at Fisk University in the spring of 1967.” Following this conference, Brooks stopped only depicting predetermined racialized interactions on a segregated Chicago street. She began to set her poems in historically white-dominated spaces, and in doing so, Brooks depicts a power dynamic between Black and white Americans where the outcome isn’t predetermined.

As America’s political climate shifted to reveal and openly discuss the country’s widespread racial injustices, Brooks’ poetry undergoes an analogous change in its characterization, its environment, and its implications of Black agency; however, it does not shift in its poetic distance from its Black characters. Comparing these elements in “the ballad of chocolate Mabbie[i]” and “Riot”—two poems taken from before and after Brooks’ attendance at the Fisk University conference—I will qualify The New York Times’ claim about Brooks’ evolution as a poet. I will demonstrate that Brooks’ setting and presentation of Black characters in her poetry has changed, but, even with this change, Brooks establishes and maintains a poetic distance from Black thought. I will then argue that this distance from Brooks’ Black characters implies that systemic racism continues to limit Black autonomy, even as a discursive political climate might make it appear otherwise.

I. Mabbie without agency: Brooks’ Poetry before 1967

In “the ballad of chocolate Mabbie,” Brooks maintains a poetic distance from the titular character as she depicts Mabbie’s interaction with Willie Boone outside of the grammar school. The ballad, originally published in Brooks’ 1945 collection A Street in Bronzeville, is the only poem in the collection that depicts an interaction between a Black and a non-Black character. With this poem, Brooks must leave the Black domestic space that dominated the rest of A Street in Bronzeville in order that the interaction between chocolate Mabbie and Willie Boone can occur. By choosing “the grammar school gates” (7) as the poem’s setting, Brooks selects a neutral area more concerned with teaching children than exploring the historical segregation between them. However, by describing a gate in this neutral space, Brooks provides a metaphorical partition that allows for the interaction between Mabbie and Willie to occur even as the gate represents a division between them.

Further, when Brooks says that Mabbie “was without the grammar school gates” (7), she uses the archaic definition of “without” to highlight that the gates separate Mabbie and Willie both physically—as Mabbie waits for Willie to come out—and metaphorically—as the deeply ingrained racism within American culture prevents Mabbie from entering the gates and interacting with Willie on an equal field.

Brooks uses her description of the poem’s setting and characters to further define this separation between Willie and Mabbie. When Brooks describes the gate between Willie and Mabbie as “pearly” (7), for example, she invokes connotations of whiteness and purity and alludes to the cliched image of the pearly gates guarding the entrance to heaven[ii]. While Willie is inside the grammar school gates—furthering his education and receiving the benefits of his privilege—Mabbie waits outside, a brown body separated from that success by a physical white gate and by the metaphorical barriers assigned to the color of her skin. When Brooks notes Mabbie as being “chocolate” (7), she implies Mabbie is both darker-skinned and an object of capitalist consumption for Willie: Mabbie seems out of place next to the whiteness of the fence, the whiteness of Willie, and the uncolored optimism of her own naïve ideas. The setting of this poem thus demonstrates how the unspoken racism of Mabbie and Willie’s time physically and metaphorically prohibits their interactions. With Mabbie standing “without” the gates, Brooks shows that Mabbie has no ability to act and change this Black-white narrative into which she is thrust.

Further, by choosing the ballad form to relate this seemingly insignificant encounter between Mabbie and Willie, Brooks emphasizes the moment’s importance in revealing Mabbie’s lack of agency. With the ballad, Brooks invokes a rich lyrical tradition defined by its simplicity, its rhythm, and its capacity to share stories important and familiar to all (Mootry). The sentences are simple—“It was Mabbie without the grammar school gates. / and Mabbie was all of seven” (7)— and the simple rhyme scheme of the poem—with words like “seven” and “heaven” or “she” and “be” (7)—emphasize the sing-song quality common to the ballad form. Further, the set structure of a ballad—the decisive repetition of the refrain “It was Mabbie without the grammar school gates” (7) and the audience’s assumed familiarity with the tale—emphasizes the ballad’s predetermined ending: underlying this ballad is the readers’ and narrator’s knowledge that Mabbie’s crush on Willie will never be reciprocated, and that such a story has been retold many times over already. The ballad form reinforces Mabbie’s lack of agency in the encounter: Mabbie might be honored by having her story recounted, but having her story heard does not change her story’s prearranged outcome. Brooks’ ballad thus recalls its “simple and direct” predecessors, but on another level, her ballad is “deeply ironic and complex” in its presentation of underlying moral themes regarding interracial discrimination (Mootry).

We can further understand Brooks’ ironic and complex use of the ballad form by considering the irregular capitalization of the ballad’s title: while Brooks inflates the importance of the encounter between Mabbie and Willie by recounting it in a ballad form, she reminds readers of its insignificance and commonplace within American life by choosing not to capitalize “ballad” or “chocolate.” This lack of respect shown to the ballad form and to Mabbie’s skin tone within the title serves as a reminder that these same feelings are shared by the society for which Brooks crafted the poem. Brooks implies that Mabbie’s story is so commonplace that it does not deserve to be capitalized correctly.

Brooks further differentiates between Mabbie and Willie by depicting their actions in different verbal voices. Though Mabbie is the first character introduced in the ballad and though the poem’s third person narrator often aligns itself with Mabbie’s perspective, whenever Mabbie is introduced, all her actions are foretold in the passive voice: “It was Mabbie without the grammar school gates / and Mabbie was all of seven” (7). By using the passive voice, Brooks makes Mabbie’s actions and her very being in the poem dependent on other objects or ideas that are usually secondary to a person. Even in the only moment in the poem where Mabbie is assigned active voice— “Mabbie thought life was heaven” (7)—Brooks gives Mabbie the active capacity for thought only to define this thought itself as passive. Verbal voice here demonstrates that Mabbie is capable of pushing against the passive voice that Brooks assigns to her. However, because the thought itself is passive, Brooks seems to indicate that the racism underlying the ballad overtakes Mabbie’s mind and denies her the agency to act otherwise.

In contrast to Mabbie’s passivity, Brooks assigns Willie active actions: he “went to school,” and he “came” out from the school gate (7). Though Willie is the second character introduced in the poem, Brooks emphasizes Willie’s higher societal importance by Mabbie’s childlike obsession with him. Just as Mabbie views her life as heaven, she views the grammar school gates as heaven’s gates simply because “Willie Boone went to school there” (7). Mabbie thus idolizes Willie as a god-figure, which emphasizes the different levels of cultural power and opportunity between the two children. This difference in voice and characterization between Mabbie and Willie shows that Willie has the freedom to act as he chooses while Mabbie does not have the same opportunity.

In addition to this disparity in voice and characterization between Mabbie and Willie, Brooks uses differences in the two characters’ language to juxtapose them further. As Brooks shift the poem’s setting and places both kids in a room dedicated to the formal correctness of grammar, Brooks assigns Mabbie the only example of Black English in the poem: “When [Mabbie] sat by him in history class / Was only her eyes were cool” (7). Using the past singular tense of “to be” in addition to the past plural tense emphasizes the difference in opportunity between Mabbie and Willie. Despite their going to the same school, Mabbie is defined by her skin tone, by her lack of agency, and by her use of Black English. Even her lack of formal grammar separates Mabbie from Willie.

With these characterizations thus made, Brooks shifts her poem to create a sense of pity for the innocence of Mabbie’s condition. When the poem’s narrator laments, “Oh, pity the little poor chocolate lips / That carry the bubble of a song!” (7), Brooks highlights Mabbie’s disconnection with reality.

Even as Mabbie’s own thoughts and description emphasize her passivity and lack of agency, Mabbie herself—at least initially—has no awareness that she is any different from Willie, despite the endemic societal barriers that make it so. Because of Mabbie’s own lack of awareness of her reality, the narrator does not argue for a change in this reality—only that readers pity Mabbie because she had not yet been exposed to the limitations assigned to her.

This request for pity rather than change foreshadows the end of the poem. When Mabbie sees Willie with a “lemon-hued lynx,” her idealized reality shatters; the “warm” feelings Mabbie had felt waiting for Willie dissipates with the cold realization that Mabbie and Willie are and will remain separate. Color imagery emphasizes this separation. The “lemon-hued lynx / With sand-waves loving her brow” directly contrasts the “chocolate companions” that will comfort Mabbie after Willie has left (7). The fact that Willie chooses a blonde white female over Mabbie should not surprise Brooks’ readers. Set during the time before the Civil Right Movement, “the ballad of chocolate Mabbie”depicts the 1940s American reality of strict segregation. Brooks encourages us to pity Mabbie precisely because the seven-year-old girl has not yet realized that she has no agency to act against the racism that pervades her existence.

Brooks further emphasizes Mabbie’s lack of agency by removing her identity as she is described among her companions after Willie has left the school. “Yet chocolate companions had she: /Mabbie on Mabbie with hush in the heart” (7). Here, Brooks uses Mabbie’s name to refer to all her Black companions. Mabbie thus becomes the name of any Black individual who has experienced similar racism embedded into their very existence. Ending the poem with the line “Mabbie on Mabbie to be” (7), Brooks shows that she does not yet believe this forced segregation—even among young children—will change in the future: she uses the repetition of Mabbie’s name to argue that Mabbie’s story will repeat. “The ballad of chocolate Mabbie” will not be the only example of systemic racism crushing the untainted dreams of a Black American, child or otherwise. The poem ends with a declaration of this racism, a revelation of a separation that seems untargetable because it is so ingrained into the underlying expectations of Mabbie and Willie’s interactions.

This separateness and Mabbie’s inability to recognize its effects on her own agency is furthered by Brooks’ use of the third person limited narrator. Given that the poem presents an encounter largely from Mabbie’s perspective, it is revealing that we do not have direct access to Mabbie’s thoughts. The third person limited narration in this ballad thus emphasizes the distance between readers and the Black characters. Even as we view the effects of racism on Mabbie, we do not understand them on a personal or deeper-than-topical level. This distance demonstrates a kind of confinement and lack of freedom for Black Americans: as readers, we are free to witness the racism that Brooks describes, but her characters are not free to share with us their active thoughts about their oppression.

II. The Agency of “It”: Brooks’ Poetry after 1967

This lack of a voice for African American thought is a defining factor of Brooks’ poetry, no matter the moment in Brooks’ career from which the poem is taken. Following the 1967 Fisk University Conference, following the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, following Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassinations, Brooks shifts in her presentation of poetic setting, characterization, and agency as she describes more integrated racialized interactions; however, she still maintains a poetic distance that prevents readers from interacting with Black thought, even in this radical new political climate. To understand the purpose of this continued distance from her Black characters, one must first understand how Brooks’ poetry shifted following the Fisk University Conference.

In “Riot,” Brooks leaves a street in Bronzeville and the grammar school where Willie and Mabbie interact to craft a poem in an area that would have historically been defined as a white space. Brooks juxtaposes John Cabot and the Black men he soon encounters in this white space to show her readers this expectation of separation—specifically the fact that Black Americans would not have been accepted in the place where Brooks places them.

To contrast John’s negative perception of desegregation and what is presumed to be his witnessing of a race riot, Brooks opens “Riot” by defining Cabot by his affluence and as a paradigm white character. Opening the poem with “John Cabot, out of Wilma, once a Wycliffe, / all whitebluerose below his golden hair, / wrapped richly in right linen and right wool” (9), Brooks assigns the perspective of the poem to a prototypical white male: John has golden blonde hair, a distinguished pedigree, and a way of dress that distinguishes him from first glance as an affluent white individual. Further, Brooks repeats the word “right” (9) in her description, emphasizing John as a representation of some ideal. The implication of John’s “rightness” thus implies that other in opposition to him will be characterized as “wrong.” John’s “rightness” becomes even clearer through the alliteration of Brooks’ description of him: the repeating first sounds of “Wilma” and “wrapped richly” create a melopoeaic synergy that causes the words of the description to blend together (9). Not only does John’s description imply a kind of white perfection, but the lack of hard sounds within this description create a soft aural harmony.

Brooks further highlights John’s characterization as a respectable white citizen by the allusions she makes in his pedigree. By choosing the name John Cabot, Brooks alludes to the fifteenth century Italian explorer by the same name who played a role in the discovery and colonization of America (“John”). The name “Cabot” also references the surname of one of the founding white families of Boston[iii] (“Cabot”). With the surname Cabot, Brooks places John directly in a white colonial lineage, establishing him as a figure who descends from the people who conquered America and eventually enslaved Black Africans. Additionally, Brooks notes that John’s mother, Wilma, comes from the Wycliffe family, a name connected to the legacy of the English theologian, John Wycliffe (Stacey). Each of allusions within John’s pedigree align him with the image of an affluent white male: John’s white ancestors afford him a privilege that allows his thoughts to be heard.

However, Brooks uses a periodic sentence to question the security of John’s affluence: after making a detailed and extensive list of everything that makes John Cabot a prototypical privileged white American, Brooks says that he

“almost forgot his Jaguar and Lake Bluff;

almost forgot Grandtully (which is The

Best Thing That Ever Happened To Scotch); almost

forgot the sculpture at the Richard Gray

and Distelheim; the kidney pie at Maxim’s,

the Grenadine de Boeuf at Maison Henri.

Because the Negroes were coming down the street” (9).

By repeating “almost forgot” three times and following each time with material examples of John’s wealth and privilege, Brooks emphasizes the almost break of Cabot’s connection to his privilege.

Immediately after Brooks constructs a 9 line single-sentence stanza, Brooks follows the periodic sentence with a single-line stanza sentence fragment to show the cause of Jon’s white discomfort. “Because the Negroes were coming down the street.” Brooks contrasts this grammatically complex sentence description of John with a jarringly incomplete thought. In the next stanza, Brooks continues using sentence fragments, further mirroring the jarring effect that John would have experienced at seeing Black people coming down the street toward him: “Because the Poor were sweaty and unpretty … / and they were coming toward him in rough ranks” (9). By introducing the “Negroes” approaching John on the street in this fragmentary way, Brooks categorizes them as lesser, as a more disjointed body compared to John’s self-assured and lengthy pedigree. Further, she removes the group’s individual identity by calling them “the Negroes” and “the Poor” (9): whereas John is assigned a name and a pedigree and a background, the people approaching him on the street are defined first by their Blackness and then by their noise—“they were Black and loud” (9)—but never by their name.

Following this collective characterization, Brooks contrasts the euphonious harmony of John’s description with John’s cacophonous view of the people approaching them. Describing the “Negroes” “in rough ranks. / In seas. In windsweep … / not detainable. And not discreet” (9), John gives the group of people approaching him a collective power not seen before in Brooks’ poetry. This power comes from the African Americans breaking from how John expects them to behave: rather than being like the “Two Dainty Negroes in Winnetka” (9), the people approaching John have an implied sense of agency to behave as they will rather than as they are expected to. It is this collective agency—not any Black individual—that frightens John. As he becomes more overwhelmed by their presence throughout the poem, John shifts from referring to them as “they” to “Negroes,” and eventually to “It” (9). When he whispers to “any handy angel” in the sky, “Don’t let It touch me! the Blackness! Lord!” (9), John reveals what causes his disgust of the encounter. Capitalizing “It” but not Blackness shows that the group of African Americans approaching John has taken on a collective identity as a monster, and it is the color of this monster that frightens him. The assertion of the group’s Blackness—the assertion of their agency—causes John to itch “instantly beneath the nourished white / that told his story of glory to the World.” Contrasting the nourishment of John’s skin to the negative imagery associated with the monstrous Black collective reveals John’s feelings about the people surrounding him. He is afraid only because Black agency creates an environment where John himself is not the only one with power.

John counteracts this lack of control by embedding himself further in his prejudice. After John calls to Jesus for protection, Brooks details, “But, a thrilling announcement, on It drove / and breathed on him: and touched him. In that breath / the fume of pig foot, chitterling, and cheap chili” (10). Just by being near John, by performing simple acts of existence—breathing and touching—the monstrous “It” overwhelms John. Through this interaction, Brookes notes that John thinks nothing of Black agency, only of Black stereotypes that reinforce his disgust. These reminders of what John would consider a once inferior race being allowed an equal existence to him “malign, mocked John” (10). This encounter inspires such a strong reaction that John’s own doubt becomes personified and speaks: “Cabot!”—naming John first by his last name to assign him respect—“You are a desperate man, / and the desperate die expensively today” (10). Following John’s communication with himself, Brooks describes a scene of chaos and disarray: “John Cabot went down in the smoke and fire / and broken glass and blood” (10).

The polysyndeton of that line emphasizes the chaos surrounding John, a chaos that directly contrasts the serenity and surety of John’s initial pedigreed description. By continuing to call John Cabot by his full name, Brooks continues to show him the embedded racialized respect expected of a white individual: even among the chaos, John still holds onto his prejudices.

The poem ends reiterating these prejudices and comparing John to a god-figure, further distinguishing John from the African American collective that surrounds him: John “cried ‘Lord! / Forgive these nigguhs that know not what they do” (10). This line encapsulates John’s persistent racism because he uses a racial slur to refer to the people around him, and he aligns himself to Jesus’ crucifixion[iv] while he does it. By saying this, John shows the readers that, despite the Civil Rights Movement and despite Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination and the following riots for equality and justice, John believes in the separation of races and the disenfranchisement of Black individuals. The people who attack him should be forgiven, John says, because they have not realized they have left their “place,” places that had been so well-defined before.

By presenting the “Riot” from this perspective, Brooks demonstrates that a shift in environment, characterization, and implied agency does not equate to a shift in Black freedom. By relating “Riot” from the point-of-view of a white man, Brooks still enacts a distance between readers and the Black characters, the same distance that is seen in “the ballad of chocolate Mabbie.” Even in describing the encounter between John and “It,” readers cannot be sure that violence has occurred. Brooks is careful not to describe any violence directly: the only action assigned to “It” is that “the Negroes were coming down the street” (9) and that they “drove / and breathed on him: and touched him” (10). Nowhere are Black individuals directly attacking John. Even the quote foreshadowing John’s death comes from John’s own “averted doubt” (10). Because of this distance between the perspective of the poem and the readers trying to objectively interpret the actions, readers cannot be certain that violence has even occurred: the violence of the scene could come solely from John’s perception of it; he could place a violence on the breaking of understood racial boundaries without himself ever being attacked.

This perspective of implied violence without the assurance of actual violence furthers the underlying belief shared between both of Brooks’ poems: Blackness in America is inexplicably intertwined with whiteness, and within this value system, describing something as white necessitates a lesser value assigned to Blackness. Between two kids, there is the underlying racism that forces Mabbie’s separation from Willie. Between John and the Black collective, John’s own racism causes him to view himself attacked by a Black expression of agency. Between the two poems, the setting changes; the severity of judgement passed through characterization changes; the perspective changes; but the underlying racism implied by Brooks’ refusal to voice Black thought remains. In this way, Brooks’ poetry, as critics claim, has evolved; however, as Brooks explores Black consciousness in white America, she reveals that this evolution in her poetry has not yet extended to an evolution in Black autonomy. As modern readers of Brooks’ works, we must ask ourselves if Black autonomy in our own society remains the same.

Poems

the ballad of chocolate Mabbie

It was Mabbie without the grammar school gates.

And Mabbie was all of seven.

And Mabbie was cut from a chocolate bar.

And Mabbie thought life was heaven.

The grammar school gates were the pearly gates,

For Willie Boone went to school

When she sat by him in history class

Was only her eyes were cool.

It was Mabbie without the grammar school gates

Waiting for Willie Boone.

Half hour after the closing bell!

He would surely be coming soon.

Oh, warm is the waiting for joys, my dears!

And it cannot be too long.

Oh, pity the little poor chocolate lips

That carry the bubble of song!

Out came the saucily bold Willie Boone.

It was woe for our Mabbie now.

He wore like a jewel a lemon-hued lynx

With sand-waves loving her brow.

It was Mabbie alone by the grammar school gates.

Yet chocolate companions had she:

Mabbie on Mabbie with hush in the heart.

Mabbie on Mabbie to be.

Riot

John Cabot, out of Wilma, once a Wycliffe,

all whitebluerose below his golden hair,

wrapped richly in right linen and right wool,

almost forgot his Jaguar and Lake Bluff;

almost forgot Grandtully (which is The

Best Thing That Ever Happened To Scotch); almost

forgot the sculpture at the Richard Gray

and Distelheim; the kidney pie at Maxim’s,

the Grenadine de Boeuf at Maison Henri.

Because the Negroes were coming down the street.

Because the Poor were sweaty and unpretty

(not like Two Dainty Negroes in Winnetka)

and they were coming toward him in rough ranks.

In seas. In windsweep. They were black and loud.

And not detainable. And not discreet.

Gross. Gross. “Que tu es grossier!” John Cabot

itched instantly beneath the nourished white

that told his story of glory to the World.

“Don’t let It touch me! the blackness! Lord!” he whispered

to any handy angel in the sky.

But, in a thrilling announcement, on It drove

and breathed on him: and touched him. In that breath

the fume of pig foot, chitterling and cheap chili,

malign, mocked John. And, in terrific touch, old

averted doubt jerked forward decently,

cried, “Cabot! John! You are a desperate man,

and the desperate die expensively today.”

John Cabot went down in the smoke and fire

and broken glass and blood, and he cried “Lord!

Forgive these nigguhs that know not what they do.”

Endnotes

[i][i] I maintain the irregular capitalization of this poem’s title as it appeared in the 1963 Harper Perennial Classics edition of Brooks’ Selected Poems.

[ii] “The twelve gates were twelve pearls: each individual gate was of one pearl. And the street of the city was pure gold, like transparent glass” (Revelation 21:21, NKJV).

[iii] From a 1910 speech representing the privilege and religiosity associated with the Cabot name, John Collins Bossidy said, “And this is good old Boston, /The home of the bean and the cod, / Where the Lowells talk to the Cabots, / And the Cabots talk only to God.” (“Lodges”).

[iv] “Then Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do’” (Luke 22:34 NKJV).

Works Cited

Brooks, Gwendolyn. “The Ballad of Chocolate Mabbie.” Selected Poems. Harper Perennial Classics, 1963.

---. “Riot.” Riot. Broadside Press. 1969. Accessed from https://yale.instructure.com/course s/44548/files/folder/Readings/Class%2022%20-%20Apr.%2011?preview=2880386. Accessed 29 April 2019.

“Cabot Family.” Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Inc. Accessed From https://www.britannica.com/topic/Cabot-family. Accessed 3 May 2019.

“John Cabot.” Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Inc. Accessed from https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Cabot. Accessed 3 May 2019.

“Lodges Aren’t Included in Original Verse.” Harvard Law Today. Harvard Law School. Accessed from https://today.law.harvard.edu/letter-to-the-editor/lodges-arent-included-in-original-verse/. Accessed 3 May 2019.

Mootry, Maria. “‘Chocolate Mabbie’ and ‘Pearl May Lee’: Gwendolyn Brooks and the Ballad Tradition.” College Language Association Journal, vol. 30 no. 3, 1987, pp. 278-293. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44321951. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Stacey, John. “John Wycliffe.” Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Inc. Accessed From https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Wycliffe. Accessed 3 May 2019.

Thorsson, Courtney. "Gwendolyn Brooks’s Black Aesthetic of the Domestic." MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S., vol. 40 no. 1, 2015, pp. 149-176. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/578776. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Watkins, Mel. “Gwendolyn Brooks, Whose Poetry Told of Being Black in America, Dies at 83.” The New York Times. 2000. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/12/04/books/gwendolyn-brooks-whose-poetry-told-of-being-Black-in-america-dies-at-83.html. Accessed 27 April 2019.