By Andrew Bilodeau

Edited by Sarah Li '22 and Lucy Gilchrist '24

“Although the mines are guarded,

The miners true and fair,

They mean to deal out justice,

A living they declare.

The corruption of Buchanan

Brought the convicts here,

Just to please the rich man

And take the miner's share.”[1]

The late 19th century was filled with labor unrest. The rise of the American Federation of Labor and the maintenance of other combative unions gave way to a chaotic final two decades of the century, which witnessed the Haymarket Affair, the Homestead Strike, and the Pullman Strike. Organizers fought bosses in one of America’s most prominent eras of stark wealth inequality, with workers winning concessions that continue to shape American life today.[2]

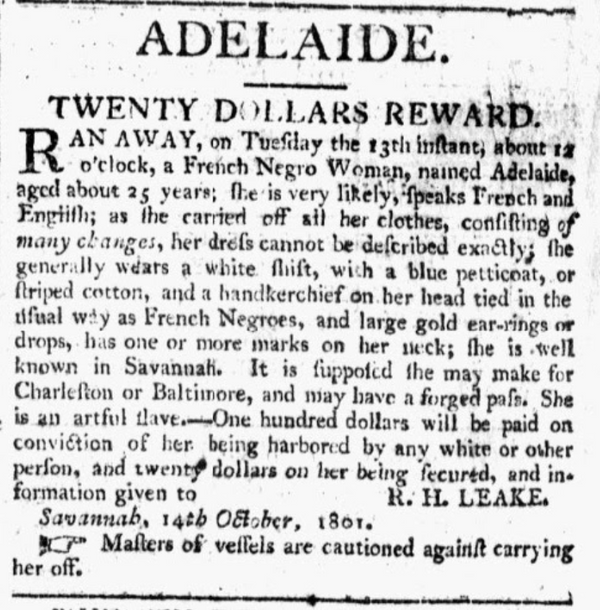

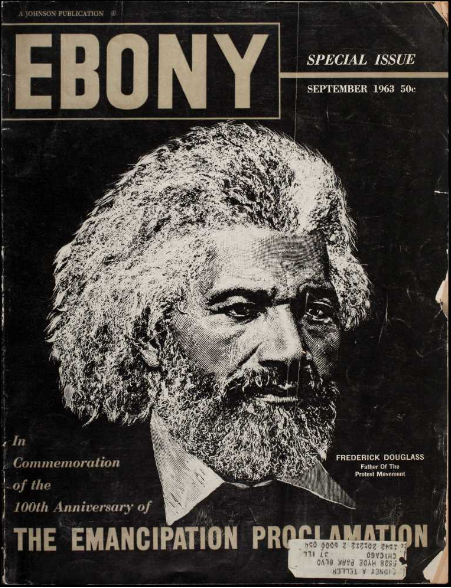

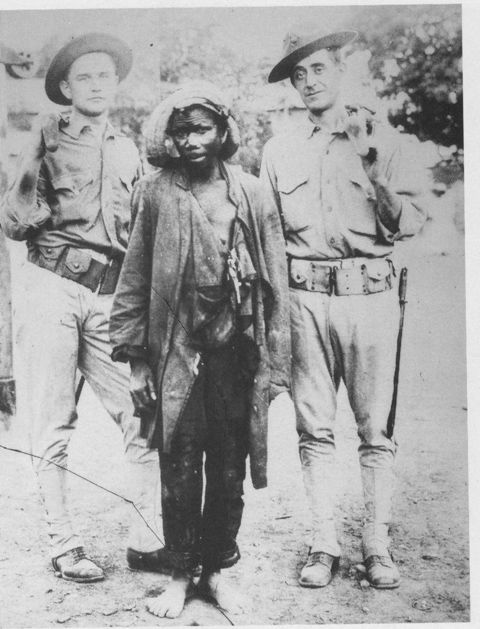

The same time period also saw some controversy grow surrounding the practice of convict leasing throughout the southern United States. The system, widespread in the postbellum South, involved state and local governments leasing inmates at jails and prisons to private companies for the purpose of providing cheap labor — often to business interests with ties close to the bureaucracy. In addition to the profit motive, the system, taking advantage of a 13th Amendment loophole, allowed for the continuation of Black relegation to second-class citizenship in the South.[3]

These two threads of historical developments - union organizing and convict labor - are often discussed separately with little overlap. However, when mining companies in Tennessee used convict labor as a strikebreaking tactic to suppress labor bargaining, they collided in an often-overlooked series of events called the Coal Creek War. Throughout 1891 and 1892, hundreds of free miners affiliated with the Knights of Labor and their supporters took up arms against their former bosses, ransacking newly-constructed prison mining camps and freeing convict laborers along the way. Their actions are widely credited by historians as essential in facilitating the end of convict labor in Tennessee, which was achieved in 1896.[4]

Some scholars, like Howard Zinn, have highlighted this as an instance of important class solidarity that resulted in radical change.[5] Others, such as Pete Daniel, have been skeptical of the angelic portrayals of the miners and their aims, pointing out that “nearly three quarters” of convict miners were Black, whereas “less than six percent” of free miners were.[6] It was personal economic gain, scholars in the second camp argue, not solidarity and a commitment to justice that motivated the miners.

However, there is ample evidence that points to a more complex picture, particularly in the conflict’s final week during which the arrests of combatants were being made. While the union miners and their leadership were made up primarily of White men, black miners were active participants of the movement who gained the respect and solidarity of their comrades. In this paper, I begin to analyze some of these sources in an effort to argue: (1) that corporate sympathizers such as the press and the state militia utilized race as a tactic to undermine the union miners and erase Black men’s contributions to the struggle; and that (2) despite these attacks, Black miners remained active and respected participants of the rebellion.

Few scholars have written about the Coal Creek War extensively, but there exists a rich historical conversation surrounding labor activism during this period as well as convict labor. In this piece, I converse primarily with Philip Foner’s Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981. In a chapter discussing the Knights of Labor, Foner cautions scholars against viewing the Knights of Labor as a site of perfect racial solidarity, but also argues for acknowledgement that its policy of being open to Black membership (including men and women) was much more progressive than contemporary organizing forces.[7] My analysis tends to agree with Foner’s assessment, while filling a large hole in his discussion of Black participation in the Knights of Labor by discussing the Coal Creek War, which goes unacknowledged in his history. I also draw on Douglas A. Blackmon’s Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, which traces the various mechanisms of repression and violence wrought against the Black community, including the practices of convict leasing and lynching.[8] Blackmon’s work serves to provide valuable background to the environment in which the Knights of Labor and their allies fought. Finally, I engage with Robin D. G. Kelley’s Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, which aids me in conceptualizing the thoughts and imaginations of Black organizers who fought in the Coal Creek War not only for justice in their own lives, but also for a free future for their communities.[9]

This article also engages heavily with primary sources. Because little was known about the identities of the combatants, let alone their race, until the end of the Coal Creek War, I utilize Tennessee newspaper records from the conflict’s final weeks, during which contemporary journalists describe arrests and battles in great detail. I find these depictions in the Chattanooga Daily Times, which was a regional paper based near the site of the war, the Journal and Tribune, a Knoxville-based paper, and the Memphis Weekly Commercial. All three newspapers maintain a heavy bias against the miners and their cause, siding with the corporate interests of the mines and the soldiers tasked with defending them. However, a critical reading reveals valuable information about the men who fought in the Coal Creek War, and their relationships with one another. Most importantly for this study, they reveal a strong case for Black heroism in the heat of battle for worker’s rights and the end of convict labor’s grip on their communities.

“The miners acted manly,

When they turned the convicts loose;

You see, they did not kill them

And gave them no abuse.

But when they brought the convicts here

They boldly marched them forward;

The miners soon were gathered

And placed them under guard.”[10]

On the night of August 15, 1892, 150 free miners descended upon a prison labor camp guarded by twenty-five soldiers. Their threat of violence was never actualized into bloodshed, as the soldiers surrendered without a fight. Moving quickly throughout the camp, the miners freed hundreds of convicts, dispatching them on trains across Tennessee where they could evade law enforcement. Upon the begging of the guards, the free miners agreed to not do any damage to the property of the mining company. In their article describing the conflict, The Chattanooga Daily Times centered the race of the convicts – mostly black – to instill fear in their readers. When discussing the group of convicts escaping by train, the paper divided them into two camps, granting/giving their emotions racialized depictions: “The negroes were happy and begged money – the White men looked surly and said nothing.”[11] In this depiction, the Daily Times chose to invoke behaviors that accentuate stereotypes of Black men as unruly and greedy. On the other hand, The Times described the White men as solemn and disapproving of the lawlessness they had witnessed. The opinion of these White men was said to be in conjunction with the “better class,” which “deplored” the free convicts “as a calamity to the section of the country.”[12]

Nevertheless, the alleged joy of the Black men on the train shouldn’t be ignored. The convict labor system in Tennessee systemically targeted Black men with flimsy and low-level charges, selling them off to dangerous mining jobs where they were deprived of the power of a union. The happiness that the Daily Times described was probably very real, as the men — at least for a short time — were free from the dangers of the mine and the brutality of their captors. Thus, they celebrated with rebellious jubilation, with music and song, with tobacco and laughter. In this way, even if they weren’t organizing with the Knights of Labor, the men freed in these battles were able to express emotions that emphasized their own autonomy and revolution – their dreams of freedom come true.

The jubilation of the freed convicts was brought about by a diverse group of men. The Chattanooga Daily Times described many leaders of the rebellion, including four Black men: John Maxwell, A.L. Spring, Sam Payne, and Ora Jones.[13] Jones was an ex-convict whose participation reflected a set of interests broader than simply economic gain for the Knights of Labor. These four were far from the only Black rebels: the Daily Times reported that “a large number of negroes were among the rioters and rendered material assistance to the White men.”

Of course, it is worth considering that the newspaper might have included such passages to foment distrust for the miner’s movement, playing on the prevailing racist frameworks of the contemporary age. This is aided by the fact that the White men earned the title “lieutenants” in the article, while the Black men are referred to simply as “rioters” and “negroes.” The presence of the Black men’s names, however, implies a more recognizable and active role for at least a contingent of people of color in the rebellion.

The following day, a party in Briceville, Tennessee was playing host to several miners fighting in the Coal Creek War. Lieutenant Perry Fyffe of the local militia requested entrance to the building, wishing to dance to the music he heard inside. When the miners attempted to push him out, he burst through them into the party, eventually finding himself in a fistfight with one of their younger associates. Presumably after receiving a beating, Fyffe left the premises and returned with reinforcements. Soldiers quickly found the man who fought Fyffe, dragged him outside, and hung him from a tree.[14]

Little is known about the boy who was killed by Tennessee militiamen, except that his name was Drummond.[15] However, the brutal manner of his murder, a lynching, could point to suspicions that Drummond might have been Black. Lynching was a fact of life for many young Black men in the Jim Crow South, where their every move could be interpreted as an act of disrespect worthy of murder.[16] While some historians might argue that his status as a free miner would make it more likely that he was White, the Knights of Labor, who comprised the primary combatants of the Coal Creek War, had more Black members than any other major labor union at the time. Black chapters of the Knights of Labor were extremely common in the South, with Virginia being the site of the highest Black worker organization with the union. Tennessee’s chapter also welcomed a sizable number of Black men, and, all in all, certain estimates place the proportion of Black men in the union at one in five on the national scale.[17] Regardless of whether Drummond was Black, his fellow miners took deep offense to his murder. They quickly engaged in a revenge mission, shooting at a nearby compound of militiamen before being forced into surrender.[18]

This surrender would be a sign of things to come. Days later, state troopers captured several ringleaders of the miners in a bloody battle that took several lives. One of those lives, Private Frank Smith, was quickly avenged when the sharpshooter who killed him was swiftly captured and hung. While the prominent White men who had admitted guilt—including Bud Lindsay, Tom Hightower, Gus Turner, and State Labor Bureaucrat G.W. Ford—were held for due process, the man who killed Private Smith was killed without a trial, referred to only as “a negro.”[19] The newspaper’s portrayal of this as a victory indicates an allegiance to the racial hierarchy that defined the contemporary South. His anonymity indicates that the mere mentioning of his race communicated the full extent of the identity he was entitled to and was perhaps sufficient to signal a point of view to the reader. The lynched Black man expressed pride in his part in the riot, boasting about his accurate shot: even in the face of death, his participation was active and enthusiastic. His fate also points to the entrenched inequality and bigotry that encompassed the response to the rebellion. White men were granted a day in court, Black men were left unnamed and shrouded by the ages.

The lynching of the unknown sniper served to emphasize the long-term violence of lynching: erasure. Without a trial to defend themselves, Black men and women were often left nameless, only identified by their crimes in the legacies of history. The Coal Creek War left many Black men to suffer similar fates, with their names only known to their comrades and loved ones. It is a loss that was recognized widely by contemporary Black activists such as Ida B. Wells, who undertook projects of documenting the epidemic lynching to preserve the humanity of its victims and to assert that they are more than just spoils for their murderers.[20]

The unnamed sniper was not the only Black leader killed that day. As state militiamen travelled to Briceville, Tennessee in a series of tactical maneuvers, they were met by Henry Whitson, described as a “notorious colored desperado, cut-throat and miner.”[21] He was immediately shot dead. While Whitson’s description as “colored” in the Knoxville-based Journal and Tribune leaves some ambiguity as to his race, the story’s headline identified him as Black. Whitson’s character in this depiction garnered a sort of horrified respect, as his description of “notorious” implied his effectiveness in battle. Moreover, he was identified as a “miner,” revealing the existence of yet another Black man who made significant contributions to the Coal Creek War. Interestingly, the Journal and Tribune included two additional accounts of Whitson’s death. One, written by the Associated Press, described him as a “negro desperado and miner’s sympathizer,” adding ambiguity to his membership in a mining union.[22] This description might have worked to discredit Whitson by implying he was an outside agitator rather than an active member of the fight. On the other hand, if Winston was not a member of the Knights of Labor and simply felt inspired by their fight, his status as a “desperado” added credibility to his aptitude in battle, as well as the ability of the miners to recruit a diverse coalition of support. The third depiction, written by another writer for the Journal and Tribune, completely stripped Whitson of his desperado moniker, referring to him simply as “a negro named Whitson, who had failed to surrender.”[23] Yet again, a member of the local press had either neglected to pay respect to the full personhood of a Black man killed in battle, or consciously worked to erase it. In all accounts, however, Henry Whitson was a brave and fearsome warrior who refused to surrender. Interestingly, an article published later that week in the Memphis Weekly Commercial listed the casualties of the Coal Creek War, naming a man called John Whitson, who was identified as a “negro miner and ex-convict.”[24] This is likely a misprint of Henry Whitson’s name, as the man described died in the same place during the same week.

Regardless of whether the man was Henry Whitson, a relative of his, or completely unrelated, his status as an ex-convict and a miner revealed the ways in which Black combatants in the Coal Creek War fought on both the fronts of economic and racial justice. As a convict who had likely experienced the leasing system and a miner who had been dismissed by local corporations for slave labor, Whitson likely crafted his own imagination of freedom during the Coal Creek War. In his Freedom Dreams, Robin D.G. Kelley wrote, “progressive social movements do not simply produce statistics and narratives of oppression; rather, the best ones do what poetry always does: transport us to another place, compel us to re-live horrors, and, more importantly, enable us to imagine a new society.”[25] In the wake of a miner’s war to liberate convict laborers, Whitson was compelled to re-live his horrors as both a convict and a miner. However, it was his radical imagination that allowed him to transform himself into the notorious desperado whose exploits found their way into the annals of the archive, escaping the violent anonymity and erasure that had plagued many men in his position. It was his ability to imagine a world in which workers and convicts were not in competition for work but united in a struggle for liberation—a world in which his past was not at war with itself but wholly devoted to justice—that, in the end, made such a transformation possible. There were doubtless many men who, like Whitson, underwent similar transformations and were able to formulate similar worlds in their imaginations, but who are lost to history. It is left to Henry Whitson to stand in for many of them, representing them all as brave and fearsome warriors who refused to surrender.

A third Black man was mentioned in the Journal and Tribune’s account of that day in the Coal Creek War. In a short paragraph, the paper described a feeling of desperation on the part of the soldiers: “The troops have been scouring the country for four miles around. Bud Lindsay is despised by all. A negro named Woody is badly wanted, and if he is caught he will be killed.”[26] Despite the newspaper failing to capitalize his name, the description of Woody as “badly wanted” painted him as an incredibly effective fighter, a high-ranking warrior, or both. His mention alongside Bud Lindsay points to both ringing true. Bud Lindsay was widely considered among the senior-most leaders of the rebellion, and the most sought-after convict in the state. Even if the newspaper was not implying an equivalence of notoriety, the fact that soldiers saw the capture of both men as priorities implied that Woody was incredibly important to the cause of the miners – so important, that if caught, he would be killed immediately.

The following day, that became a reality. Bud Lindsay and Woody approached a group of militiamen who were camping out near Coal Creek. Convincing the men that they were sent by the state to prepare wires for the camp, they were left to work on their own. Quickly, the two men scurried to the site of their job, with Woody pulling out pliers to begin the work. Instead of fixing the wires, they began pulling at and destroying them in an attempt to disable them. Their work was almost done when Colonel Sevier, a daring officer who had recently suffered a gunshot wound, became suspicious of their occasional panicked glances at the camp. Before he could fully examine the men, they finished their work of sabotage and ran quickly to a handcar on the tracks to make their escape.[27] Soldiers quickly called out to Lindsay and Woody, calling on them to stop their escape attempt and began (beginning) to run toward them. Colonel Sevier yelled ahead to guards down the track, who intercepted the handcar to capture the men. A struggle ensued, resulting in Woody’s escape and Bud Lindsay’s capture.[28]

The risk undertaken in this mission by Lindsay and Woody testifies to the trust shared by the two men, and adds to the mounting evidence that Woody was an essential part of the rebellion’s tactics. A covert mission in war was often left to the most loyal of supporters, meaning Woody – like the Black men captured and killed in the war’s final weeks – had shown himself to be a true believer in the cause. Finally, the way in which the men escaped eliminated the possibility of Woody being used as bait or diversion left behind to take arrest in a moment of betrayal. Instead, the men ran to the handcar and escaped together. Lindsay sacrificing his own freedom and preserving Woody’s suggests not only a mutual respect and trust between the two, but also an acknowledgement from Lindsay that Woody was an important figure for the rebellion and that his escape would be beneficial for the cause.

The Memphis Daily Commercial’s account of the events, on the other hand, all but erased the notoriety of Woody, who was only referred to as an anonymous associate of Lindsay.[29] The centrality of Whiteness in this act of risky heroism was typical of Tennessee’s newspapers, who tended to portray Black members of the movement as auxiliary or simply meddlesome. However, Woody would meet militiamen again, only increasing his notoriety in the minds of Tennessee’s soldiers and capitalists.

Colonel Sevier eventually found his way to the miner’s camp, approaching alone as a diplomatic force trying to forge peace. As he entered the camp, he was met with a revolver cocked a few inches from his face. The Colonel instantly recognized the person holding the revolver as Woody, the man who had cut the wires with Bud Lindsay. Woody, enraged with the Colonel, looked ready to fire when a White miner held him back, knocking his gun to the ground. Upon his return to the camp, Sevier relayed to the local press that Woody was a wanted man, and ordered his soldiers to shoot on sight.[30]

The local press’s descriptions of Sevier’s encounter with the miners were scanty. However, the fact that Woody was not detained, still had his revolver, and was able to greet an emissary from the state implies that he probably was not severely punished by the other miners for failing to prevent the capture of Lindsay. When contrasted with the soldiers’ reaction to Drummond’s brawl with Fyffe —which resulted in a lynching — the fact that Woody maintained a good status at the camp after Lindsay’s capture reflects at least a level of mutual respect between himself and the other miners. This context points to the assertion that Woody’s revolver being batted out of his hand was an act of protection for Woody as well as for the other miners, rather than a flagrant sign of disrespect. It was also evident that Woody had continued to garner the fearful respect of the state militia, as there was with yet another official calling for his head in desperation. His latest mission on its own had made him a wanted man, but when Colonel Sevier learned of calls for Woody’s head before his mission with Lindsay, his notoriety doubtlessly increased substantially. In addition, Woody had his name mentioned alongside Bud Lindsay yet again. Combined with the high risk of his mission with Lindsay, this continued association of the two implies a close, or at least trusted, partnership. All evidence points to the fact that Woody was a high-ranking and essential figure among the miners in the Coal Creek War whose actions managed to overcome his erasure.

“I am in sympathy with the miners,

As everyone should be.

In other states they work free labor,

And why not Tennessee?

The miners true and generous

In many works and ways,

We all should treat them kindly,

Their platform we should praise.”[31]

John Maxwell, A.L. Spring, Sam Payne, Ora Jones, Drummond, Henry Whitson, the unnamed sniper, and Woody were not anomalies. Rather, they remain indicative of the significant influence of Black men fighting for the rights of their fellow workers and the freedom of their community. Many of them, like Henry Whitson, were likely former convicts as well as miners, two identities that—in many other labor disputes—would have represented opposing sides of organizer and strikebreaker. However, in these dreams of freedom, they were united against a common enemy of exploitation and repression.

In their fight for their envisioned future of freedom, the Black men of the Coal Creek War were the victims of an array of violence from literal murder to historical erasure. All the while, their race was utilized as a tool against both the validity of their cause and their individuality as warriors. All the while, they served throughout the ranks of the war, acting as snipers, desperadoes and high-ranking confidantes. In the end, their deeds gained fame that overcame the crushing passage of time.

The men fought valiantly to earn the admiration and respect of their fellow miners as well as the fear of Tennessee’s militiamen. This framework, however, shrouds the true motivations of the Black warriors in the Coal Creek War. As Robin D.G. Kelley wrote, “in most cases, however, the critical visions of Black radicals were held at bay, if not completely marginalized.”[32] The men in this story were not seeking the approval or fear of White liberals and reactionaries in their quest. Rather, they were motivated by their own “critical visions” of the world they lived in, and sought freedom on their own terms.

The intimate thoughts and motivations of each individual man discussed in this story are probably lost in the archives of history. However, study of their context and actions can still be analyzed in an attempt to depict them on their terms as they actively added to and formulated the visions of freedom the Coal Creek War was fought for. They led, they fought, and they dreamed of a new world – one that is still possible, if we too dare to dream.

Bibliography

Blackmon, Douglas. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2008.

“By Associated Press.” The Journal and Tribune. August 21, 1892.

Daniel, Pete. “The Tennessee Convict War.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34, no. 3 (Fall 1975): 273–92.

Foner, Philip S. Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981. Reprint Edition. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2018.

Green, Archie. Only a Miner: Studies in Recorded Coal Mining Songs. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1972.

“Hung Smith’s Murderer.” The Journal and Tribune. August 21, 1892.

Kelley, Robin D. G. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2002.

LeFlouria, Talitha. Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

“Majesty of the Law.” The Chattanooga Daily Times. August 24, 1892.

“More About Lindsay.” The Memphis Weekly Commercial. August 24, 1892.

“Tennessee’s Shame and Disgrace.” The Chattanooga Daily Times. August 16, 1892.

“The Military Forces Do Vigorous Work.” The Journal and Tribune. August 21, 1892.

“Took 100 Prisoners.” The Journal and Tribune. August 21, 1892.

Endnotes

[1] Each section begins with a verse from the song “Coal Creek Troubles,” which was inspired by the Coal Creek War and its combatants. From Archie Green, Only a Miner: Studies in Recorded Coal Mining Songs (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1972).

[2] Pete Daniel, “The Tennessee Convict War,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34, no. 3 (Fall 1975): 273–92. 274.

[3] Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2008).

[4] Pete Daniel, “The Tennessee Convict War,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34, no. 3 (Fall 1975): 273–92. 273.

[5] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York, NY: Harper Perrenial Modern Classics, 2005).

[6] Pete Daniel, “The Tennessee Convict War.” 274.

[7] Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981, Reprint Edition (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2018). 47-73.

[8] Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2008).

[9] Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2002). ix-12.

[10] Archie Green, Only a Miner: Studies in Recorded Coal Mining Songs (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1972).

[11] “Tennessee’s Shame and Disgrace,” The Chattanooga Daily Times, August 16, 1892.

[12] “Tennessee’s Shame and Disgrace,” The Chattanooga Daily Times, August 16, 1892.

[13] “Majesty of the Law,” The Chattanooga Daily Times, August 21, 1892.

[14] Pete Daniel, “The Tennessee Convict War,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34, no. 3 (Fall 1975): 273–92. 289.

[15] Pete Daniel, “The Tennessee Convict War,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34, no. 3 (Fall 1975): 273–92. 289.

[16] Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2008).

[17] Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981, Reprint Edition (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2018). 48.

[18] Pete Daniel, “The Tennessee Convict War,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 34, no. 3 (Fall 1975): 273–92. 289.

[19] “Hung Smith’s Murderer,” The Journal and Tribune, August 21, 1892.

[20] Talitha LeFlouria, Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

[21] “The Military Forces Do Vigorous Work,” The Journal and Tribune, August 21, 1892.

[22] “By Associated Press,” The Journal and Tribune, August 21, 1892.

[23] “Took 100 Prisoners,” The Journal and Tribune, August 21, 1892.

[24] “Names of the Dead,” The Memphis Weekly Commercial, August 24, 1892.

[25] Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2002). 9.

[26] “Took 100 Prisoners,” The Journal and Tribune, August 21, 1892.

[27] “More About Lindsay,” The Memphis Weekly Commercial, August 24, 1892.

[28] “More About Lindsay,” The Memphis Weekly Commercial, August 24, 1892.

[29] “More About Lindsay,” The Memphis Weekly Commercial, August 24, 1892.

[30] “More About Lindsay,” The Memphis Weekly Commercial, August 24, 1892.

[31] Archie Green, Only a Miner: Studies in Recorded Coal Mining Songs (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1972).

[32] Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2002). 6.