By Allison Lau

Edited by Cynthia Lin '23 and Tiana Luo '24

By the mid 1960s, Oakland’s predominantly Black urban ghettos, like others across the nation, represented to many Black radicals the “concrete inner city jungles of Babylon”, as a metaphor to describe how the American state openly terrorized, oppressed and killed Black people on its streets and as a call to reclaim the neighbourhood (Self 2003, 14). To young Bobby Seale, local police forces were “occupying our community like a foreign troop that occupies territory” (Bloom, Martin 2013, 46). The lack of community control over political and economic resources, and common occurrences of police brutality were just some of the things that Seale felt needed to change drastically. Seale and his comrade Huey Newton joined groups such as the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) but were disappointed to see a lack of concrete action. These groups talked theoretically about the problematic system, without recruiting or galvanizing the often poor and under-educated community members they claimed to represent (Newton 1973, 107).

Bobby Seale and Huey Newton formed the Black Panther Party in 1966 as a manifestation of Black Power and in direct response to the police brutality the pair had grown up witnessing. The Panthers challenged the state by implementing both a rhetoric and policy of armed self-defense. By asserting power against what they considered a colonial state, and by standing up to the police, they hoped to organize and build Black political power (Bloom, Martin 2013, 50). Furthermore, they wanted the ‘fascist pigs’ out of their neighborhoods, instead reclaiming control of institutions within their community that kept them oppressed by appealing to ‘the brother on the block’.

In this essay, I seek to answer the question: how did the colonial interpretation of the distribution of space, resources, and the police’s monopoly on the legitimate use of force in Oakland lead to the development of the Black Panther Party’s platform for self-defense and self-determination? In the first section, I briefly explain the theories of Anthony Marx and Charles Tilly. Their works provide an excellent framework for understanding the state and economic processes that consolidated the Panthers’ policy choices.

In the second section, I will examine the conditions which created the perfect pressure cooker in which mass protest thrives. More specifically, I argue that an urgent need for the Black community in Oakland to mobilize was created at the intersection of racist urban redevelopment policies, systematic exclusion from political and economic institutions, and the monopoly on armed force by the state. Together, these forces created a system determined to impose its will onto excluded subjects. The Panthers were able to direct that feeling of injustice felt by the community into a concrete policy of armed self-defence and Survival Programs such as free breakfasts for children, sickle-cell anemia tests, and food baskets (Newton 1973, 330).

In a broader sense, the development of the Panther’s Party platform reflects an understanding of a Black identity formed separately from ‘White America’, specifically one formed around the experience of working-class African-Americans. The basis of the ideology stems from the understanding that capitalist and colonial pressures dictate how geographical, social, economic and political resources are distributed within and between states. To understand where the notions of shared separate identity and self-help come from, I appeal to the earlier mass mobilization of Garveyism. In his book, The Age of Garvey, Ewing describes ‘Garveyism not as an ideology but as a method of organic mass politics’ (Ewing 2014, 6). Like the Black Panther Party, Garveyism is a dynamic force intrinsically tied to the particular political climate in which it developed, rather than a stationary set of ideals and values. Both demonstrate that the political and economic conditions of racialized durable inequality are a precondition for radical mobilization. By comparing the two revolutionary movements, I answer the broader question of: why does a Black identity with goals of self-determination develop in the conditions of capitalist, colonial control of the distribution of space, resources, and political power?

Finally, I conclude with the Party’s legacy. Even though Marx argues that after the Civil Rights Movement, concrete gains were more difficult to aspire to, changes occurred in the justice system and police system as a result of mass mobilization. I explore these changes and at the end of this section, and reflect on the questions of ‘why did Oakland specifically become a site of mobilization for Black Americans?’ and ‘why could the Panthers specifically bring about the changes other organizations could not?’ The Panther’s manifesto of Black power, self-help, and self-defense was ultimately a decolonizing liberation project in response to the geopolitical context of internal American imperialism that manifested in racist urban development policies, systematic exclusion of African-Americans from decision-making positions, and a violent, racist police force.

Theoretical models of mass mobilization

Based on western liberal conceptions of statehood, modern sovereign states, such as the U.S. and California are normatively defined by rule of law, the right to rule over the population, and monopoly over the use of legitimate violence or physical force within particular territorial boundaries (Gilpin 1981; Hudson 1988; Rice and Grafton 1994; Weber 2013). This means that the state maintains the exclusive right to the means of and authority over violence and coercion, enacted through police, judicial and military institutions. The Panthers aimed to challenge this colonial conception of what and whose violence was considered justified. They did this through collective self-defense that exercised their (uniquely American) Second Amendment right to bear arms.

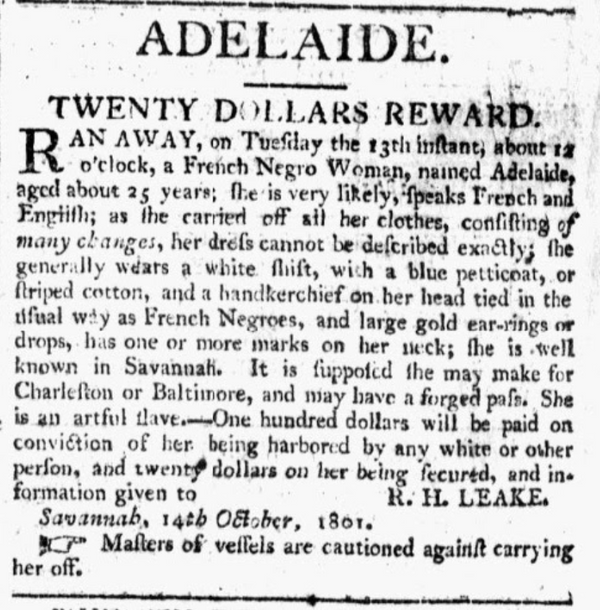

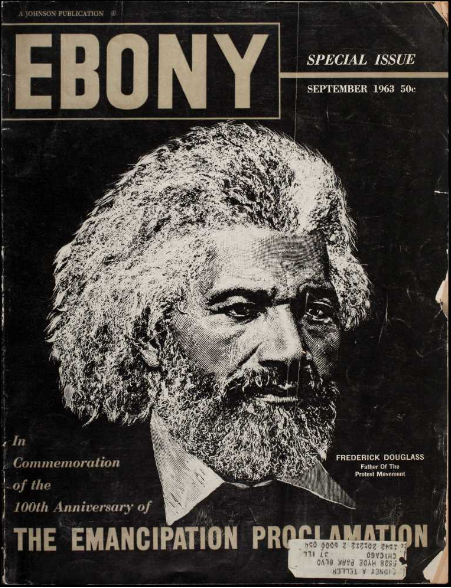

While there are many theoretical models of mass mobilization in the United States, Charles Tilly’s model of durable inequality and Anthony Marx’s conceptions of race-making provide the best framework for understanding the processes behind the Black Panther Party’s movement. In his book Making Race and Nation, Marx argues that race-making occurs from above and from below. He traces through distinct eras in American history, demonstrating how the state created notions of racial categorization and how black mobilization occurred through important moments in American history. During Reconstruction after the Civil War, the consolidation of a coherent (white) nation-state and preserving stability in the face of such a deep division between northern and southern whites, took precedence over helping African-Americans, which he coins “race-making from above”. Amidst feelings of disappointment and white consolidation, the first wave of black consciousness (or race-making from below) arose.

Marx argues that the early Civil Rights Movement was successful in its aims for two reasons. Firstly, the federal government had consolidated and became much more centralized, meaning it could act more unilaterally in response to protests. State laws could more easily be challenged and changed, and the federal government could more effectively intervene. Secondly, Jim Crow laws, a product of the Reconstruction era, provided the Civil Rights Movement with specific legal targets. The repeal of these laws resulted in legal action towards desegregation and the legalization of racial equality through the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act. As the focus of Black mobilization shifted to the North and to Black Power after the Civil Rights Movement, Marx argues the movement failed to produce concrete change because they lacked similar laws that were targeted in the South. However, I challenge Marx’s state-centric conception of race-making from above and argue that economic actors also were important in shaping race. Furthermore, I argue that the Black Panther Party still had specific legal agendas, even if there was no legislation that explicitly established inequality, and, as a result, they were able to achieve concrete reforms.

Tilly’s framework fills the gaps in Marx’s analysis pertaining to the later Civil Rights Movement. In Durable Inequality, Tilly explains the processes of economic exploitation and opportunity hoarding that turn bounded categories, such as race and gender, into categorical inequality. Borrowing from Karl Marx’s theory of exploitation, Tilly argues elites (those who control resources) have a vested interest in maintaining categorical inequality because it creates the conditions for profit. Specifically, it allows elites to extract returns from the labor of subordinate groups without fully sharing the returns. Furthermore, it creates conditions of opportunity hoarding, where elites control access to resources like jobs and education to people of a particular bounded category, excluding subordinate groups. Tilly argues that in order to reduce the costs of maintaining internal boundaries between groups and increase their stability, institutions import pre-existing shared understandings or solidarities, a process he calls ‘emulation’ of outside categories. As a result, these divisions, as the basis of categorical inequality, appear ‘natural’ and different structures and institutions begin to resemble each other more closely.

Together, these theories explain how race informed the distribution of space, resources, and the legitimate use of force in Oakland, leading to the development of the Black Panther Party’s platform of self-defense and self-determination. Tilly’s framework explains the processes behind race-making from above, beyond Marx’s contention of state-centric intra-racial white consolidation. His conception of durable inequality helps to explain how different facets of Oakland’s geopolitical context came to resemble each other in stark racial divisions and exclusion of African-Americans, specifically why race-making from above was so consistent across political, economic and police institutions. Marx, however, considers how the production of categorical inequality is not simply an elite process. Mobilization from below in the form of solidarity within pre-existing identities and boundaries, provides a good framework for understanding how grassroots movements, like the Black Panthers, emerge.

The Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland

Space: racist urban redevelopment policies

Space is a fundamental aspect of the Black Panther Party’s self-defense platform. The space that the Panthers sought to protect was that of the urban ghetto, formed initially by mass migration of Black families and individuals out of the South into Northern urban areas with the promise of jobs during World War II. A series of racist policies exacerbated residential segregation and deteriorating conditions found within old city centers. Programs to revitalize areas turned into projects of profiteering that continually excluded the Black community, rationalizing racism as an economic calculation (Self, 2003, 160).

The Bay Area was especially attractive because of its expanding wartime economy, but the promises of economic, political and social freedom as opposed to the Jim Crow South rang false once the war was over (Self, 2003, 26). Jobs started to disappear or moved to white suburbs, “leaving sprawling black ghettos in their wake” (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 27). Programs such as the Metropolitan Oakland Area Program (MOAP) recast the goal of urbanization into one of suburbanization, where mini cities of both industry and residence surrounding the downtown core would be connected by a series of highways and rail (Self, 2003, 27). These brought the promise of harmonious ‘garden communities’ that would dissolve class tensions—the possibility of being a homeowner had opened up to the employees and not just the employers (Self, 2003, 30). This quelled labor tensions arising out of dissatisfaction in white laboring classes and recognized the political power that labor leaders had accrued during the New Deal and wartime expansion (Self, 2003, 35).

However, this idyllic picture of home-ownership was not extended to Black workers. Since the 1930s, strict practices of redlining had sought to keep neighborhoods homogenous. For example, home-lending regulations denied Black people mortgages to buy houses in white neighborhoods, physically excluding Black homeowners from spaces categorized as ‘white’ (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 28). Redlining was not the only way that residential space was manipulated. Interest-rates were often higher for African-Americans, and real-estate brokers often sold houses at twice the price they were bought at to discourage Black people from moving into predominantly white neighborhoods (Self, 2003, 166). Similarly, white homeowners resisted racial integration through suburban flight and fighting legislation that would allow African-Americans to purchase houses wherever they wanted (Self, 2003, 168).

Limited in where they could purchase or rent homes, much of the African-American population resided in older homes in West Oakland. However, redlining practices designated Black and mixed neighbourhoods as ‘high risk’, which meant receiving credit for home improvement or maintenance was nearly impossible (Self, 2003, 143). Because of this, the old city centers began to deteriorate and social problems like crime and disease rates began to climb. In the late 1940s and 1950s, urban redevelopment schemes were created to rehabilitate cities across America that were in post-industrial decline. Both federal and state governments passed laws and provided funding for rehabilitating these areas. However, rehabilitation projects focused mainly on making property profitable and keeping neighborhoods stable (Self, 2003, 136). Many neighborhoods or sections of neighborhoods were completely bulldozed to make room for middle-income homes, businesses, and transportation. Since the projects focused on the most deteriorated areas and lack of credit available for home improvement disproportionately occurred in Black neighborhoods, African-Americans suffered most. Redevelopment in Oakland became equated with ‘Negro removal’ (Self, 2003, 140) and the physical destruction of Black neighborhoods. Transportation links, such as major highways and Bay Area Rail Transit (BART) cut across residential areas and separated neighborhoods from downtown. Furthermore, these transportation links often bypassed Oakland completely, taking commuters straight to San Francisco, along with investment, capital and infrastructure. Instead of a thriving community, Oakland had become a transportation crossroads.

Institutions like banks and broker agencies, mandated de facto Jim Crow segregation of physical space. In line with Marx’s argument, divisions between white populations (in this case, bosses and their employees) were reconciled in the form of democratizing property ownership, and Black communities paid the price. Class consolidation of whites in the area compounded with the physical separation in space of Black versus white communities to form a stark segregation. It is under these conditions that spaces were viewed as belonging to the white community or belonging to the Black community. The state funded redevelopment programs to invigorate an economy that benefitted white workers and provided stability to white neighborhoods while Black people were displaced and forgotten. Space was important to the state for reproducing a subordinate Black identity through designating the space belonging to Black communities as having lower value. Moreover, despite ‘equal’ claims to citizenship, African-Americans were still denied ownership to particular desirable residential areas on the basis of race.

Contrary to Marx’s argument, this was not just a state-centric process. Opportunity hoarding by brokers and white homeowners meant that homes in white suburbs, where jobs and taxes were funnelled into, remained in white ownership. White suburban neighborhoods received more job openings, better funding for schools, which opened doors to the booming service economy, and were more likely to be policed and governed by local residents with local knowledge and sensitivities. The value-producing resource of the home meant more than just owning property; it included all the advantages of living in the ‘right’ neighbourhood. Those who controlled access to it prevented those advantages from expanding beyond particular bounded categories of racial distinction. For them, space was an important commodity to accumulate; they utilized “racialized boundaries that already exist[ed] as a way of reducing an insubordinate population’s power” (Tilly, 2002, 93).

The Black Panthers, like many Black nationalists before them, conceived of a Black homeland, separate from white America, in response to white consolidation. Race-making from below carved out a psychological and physical space that belonged to Black people. The homeland was not Africa but “American ghettoes, where police (the ‘pigs’ of the state) patrolled the borders as the agents of an imperial power” (Self, 2000, 768). The Black Panthers rejected the de-racialization of space that the Civil Rights Movement advocated for; they argued “the power of African Americans lay precisely in their spatial confinement” (Self, 2000, 769). They recognized the local conditions and social relations of the Black urban ghetto. It is because of this understanding of localized space that the Black Panther Party was able to concoct a platform of self-defense contingent on the local conditions, needs, and identities. They aimed not just to “eliminate black oppression but also to enhance black culture and black lifestyle” specific to the Oakland ghetto (Tyner, 2006, 107). Space was important; even if it was something shaped by outside forces, it still belonged to them. The Panthers’ goal was to reclaim and protect it.

Systematic exclusion: transformation into a colonial entity

The systematic exclusion of African-Americans from physical, political, economic, and social power and resources transformed the black urban ghetto from a segregated neighborhood to a colonial space. American racism “developed out of the same historical situation [as colonialism] and reflected a common world economic and power stratification” (Blauner, 1969, 395). Black ghettos are distinct from other ethnic enclaves, especially those arising from immigration, precisely because of their top-down creation and the “extent to which their segregated communities have remained controlled economically, politically, and administratively from the outside” (Blauner, 1969, 397). Without channels of proper political representation, African-Americans had little leverage to change local problems. The War on Poverty, for example, did not change the structural problems causing mass unemployment and low-skilled workers. Most elites attributed the deterioration of old industrial city centers to “blight rather than as a symptom of social inequality” (Self, 2003, 139) because they lacked a nuanced understanding of the circumstances that caused poverty and joblessness. As redevelopment of Oakland continued, the Port experienced a boom. Modernization and mechanization of the Port led to economic success (Self, 2003, 153); however, this only reinforced Oakland’s position as a crossroads for transportation. More importantly, the profits of this boom did not return to the city but instead went to the private producers and shipping companies controlling the local economy (Self, 2000, 771).

As an increasing service economy developed, de facto racial exclusion continued due to requirements of college degrees and historical resistance to hiring African-Americans even at entry-level (Self, 2003, 172). This informal racialized categorical exclusion from economic institutions and from positions of power within them demonstrates that state power is not the only way race-making from above occurs, rather market forces are equally important since they can shape how economic resources are distributed. Since these companies succeeded in revitalizing Oakland and bringing in money, investment, and stability following urban redevelopment plans, neither the federal nor state governments were willing to intervene, especially to support the interests of subordinate groups.

That is not to say political power within the state is irrelevant—rather it works in tandem with economic power to systematically exclude African-Americans. Decision-makers for policies that directly affect Black communities are often white elites from outside the community. For example, the lack of representation for the poor, urban, Black population in the War on Poverty helps to explain why the programs focused more on expanding existing social services and ensuring local commercial enterprises contributed resources and jobs to the community. In fact, it is because of the Black population’s economic powerlessness that the state was largely able to ignore their demands. Margaret Somers’ framework of the contractualization of citizenship further explains this as a process by which citizenship becomes a market-place exchange as society begins to value a self-regulating market as the most efficient way to run all aspects of political, economic and social life (Somers, 2008, 87). A result of the contractualization of citizenship is that ‘the unemployed or underemployed are stigmatized as lacking moral worth’ (Somers, 2008, 72). Therefore, a state’s moral duty to a citizen is dependent on the extent to which they can create a symbiotic relationship. Unable to provide anything in exchange “for what is now the privilege of citizenship”, they are considered outside citizenly obligation (Somers, 2008, 72, 89).

One of Oakland’s prominent postwar political ideologies rested on the populist-conservative tradition, similar to the market fundamentalism Somers identifies as the underpinnings of the contractualization of citizenship. Both schools of thought privilege private rights and understand “liberalism’s limits through property and homeownership” (Self, 2003, 7). In other words, being a consumer and property-owner, and contributing back to the state and economy allows one to have a stake in political and economic decisions. Despite developments for social programs in the New Deal and Great Society, the state was ultimately a liberal, capitalist entity and favoured actions that could operate in a marketplace of competition and derive the most profit. Thus during urban redevelopment projects, revitalization of poor inner city neighbourhoods was to ensure property values were not depreciated, and extending ownership to (white) workers in suburban areas aimed to boost “consumption by a homeowning working class yielding economic growth and social stability” (Self, 2003, 34).

For Black communities in the city, racialized poverty and unemployment, the loss of jobs to white suburbs, the privatization of industry and the Port, and the increase of service sector jobs that historically or systematically excluded them became a massive barrier to political leverage and representation. The government felt little to no responsibility to effectively redistribute power. The combination of its belief that urban poverty and widespread joblessness meant these community members failed to fulfill their obligations of the “social contract” of citizenship and the “long and deeply entrenched wrongs of American racism” produced a group of individuals without political or economic power, and a disincentive for the government to engage with their demands (Somers, 2008, 101). Somer’s account links Marx’s race-making from above to Tilly’s account of economic organization and creates a robust picture of how powerful institutions outside of the community shaped the political and economic resources available to urban African-Americans.

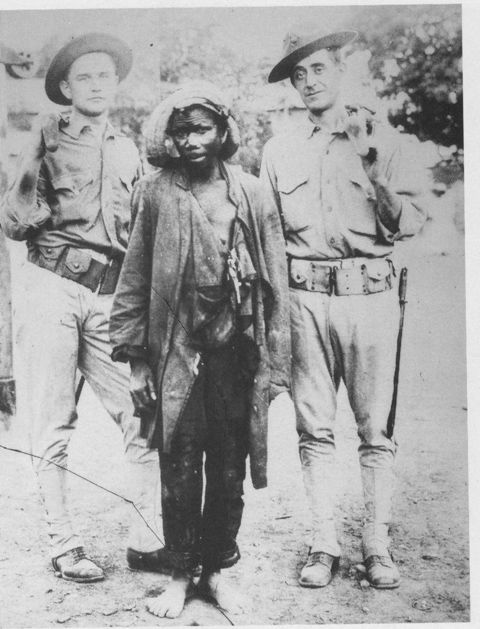

The external control of decision-making power in Black urban ghettos represented an imperial model of colonialism, defined as the establishment of political and economic domination over foreign space and peoples, usually of different race and culture, and usually accompanied by exploitation of land, people and resources with formal recognition of power differences (Blauner, 1969, 394). On a broad level, American racism and internal imperialism was an emulation of earlier larger global structures of power that had privileged the white male. Although it was not an economic organization as Tilly’s model outlines, the American internal categories reproduced existing racial hierarchies, lowering transaction costs and maximizing stability among white citizens.

In response, the Black Panthers emphasized community control of the ghetto through owning or at least directly controlling the key institutions within its borders (Blauner, 1969, 402). Without this control, they remained shackled to the will of a nation that had a vested interest in continuing to exploit their space and people and reproducing colonial relations and racial hierarchies. Not simply a nationalist group, Tyner describes the Panthers as a “grassroots organization formed to address local concerns” (2006, 109). Because they had local knowledge and understanding of how policies can impact the community, they did “what the poverty program claimed to be doing but never had - giving help and counsel to poor people about the things that crucially affect their lives” (Newton, 1973, 115). As members of the community, they were able to fix the problems they experienced rather than just mitigating symptoms by linking these symptoms to their root causes. For example, children did better at school if they had eaten breakfast, so the Black Panther’s launched a free breakfast program for children to try and ensure that no child would go to school hungry (Tyner, 2006, 111).

These Survival Programs did not just provide a temporary remedy for the symptoms of systematic discrimination, exclusion, and poverty, like government-implemented programs; rather, their primary goal was to regain control of the institutions, like schools, within the community in order to end all forms of exploitation (Newton, 1973, 167). The Panthers understood that “historical racial oppression was linked to the specific injustices of a capitalist metropolitan order that developed certain places and victimized, underdeveloped, others” (Self, 2000, 769). Race-making from below and mobilization then occurred through “educating and revolutionizing the community” to draw their attention by fighting problems that they identified with (Newton, 1973, 120). These problems were the consequence of the unequal distribution of resources and ‘All power to the people’ meant uprooting the system that distributed these goods, services, and profit in the first place, to take control of decisions that directly impacted the community at large.

Police monopoly on power

Police brutality and murder was the main justification for armed self-defense. While all institutions of power needed to be reclaimed in order to benefit the community, the police were particularly imperative because they were the most concrete example of imperial oppression in the colony of the ghetto. Imperial oppression was not just psychological but also physical violence and murder. Inspired by Community Alert Patrol (CAP) in Watts, Seale and Newton decided that monitoring the police from a safe distance to ensure justice ensued was not enough (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 39). Taking advantage of their right to carry unconcealed weapons, they decided that in order to challenge the police force, they would need to come from a position of equal power: “With weapons in our hands, we were no longer their [the police] subjects but their equals” (Newton, 1973, 120).

Colonial occupation and control is intrinsically militaristic in nature as force is used to assert domination. Newton argued it was the police who performed this role, brutally and illegitimately “occupying our community like a foreign troop that occupies territory” and acting as “the immediate barrier to self-determination” (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 46, 67). As an external political, militarized force, they were “the most crucial institution maintaining the colonized status of Black Americans” (Blauner, 1969, 404). The problem with the police was two-fold. Firstly, the police were not usually members of the community and therefore lacked knowledge of local sensitivities or conditions, contributing to blatant racism on the force. Despite the fact that 31% of the population in Oakland was Black, only 4% of the police were (Blaunder, 1969, 405). Secondly, the police controlled the community through force because they were armed and backed by the state. Armed self-defense, Seale and Newton argued, counters and minimizes police abuses. If the very people who were meant to protect the community harmed the community instead, members of the community should mobilize to protect themselves.

In North Richmond, the death of Denzil Dowell at the hands of the police in 1967 was a watershed moment in the Black Panther Party’s history (Newton, 1973, 138). As this was not an isolated incident of police abuses, it stressed to the Black community the urgency to act. Reports on the incident from police were cursory and contradictory, but the jury on the case ruled that the shooting was justified because Dowell had been committing a felony (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 50). Petitions for a full investigation by the city or state police departments to provide recourse for the family and community were ignored or delegated to higher authorities. Dowell’s murder showed the extent to which the state had accumulated the legitimate use of violence and force to oppress the community from above.

The Black Panther’s introduction of the idea of armed self-defence provided the solution that no other groups were willing to pursue (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 55). Moreover, they captured the injustice that the community felt because, unlike the police and political institutions, they belonged to the community and shared grievances and fears of being the next police brutality victim: “If Denzil Dowell could be killed by the police with impunity, so could any young person in the neighbourhood.” (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 55). The Panthers mobilized and helped to shape the urban African-American identity that developed from internal imperialism and the racialized spatial and power confinements. By identifying the police as the enemy, the ‘brother on the block’ became the central subject of the Party’s platform.

Furthermore, the Panthers’ colonial explanation of the police justified armed self-defense. As anti-colonial revolutionary Franz Fanon posited, liberation was a struggle against psychological and physical colonization. America had created the urban ghetto similarly to the way Europe created the Third World, where the “legitimate agent, the spokesperson for the colonizers, and the regime of oppression, is the police officer” (Fanon, 1963, 3, 58). For Fanon, violence is transformative: the only means to challenge colonial violence and overthrow colonial oppression in its totality. Thus, decolonization is a process of destruction and rebuilding, the creation of a society anew. Armed self-defence and violent rallies in response to police brutality follow this logic; the purpose is to challenge the colonial oppression of the police, overthrow their jurisdiction and build a new organization that would protect and liberate the people. The process of race-making from below was a result of the colonized experience of oppression, an opposing identity to the racist police officer and a desire for liberation from both.

As the Panthers’ influence grew nationally, they became the vanguard of the revolution, a legitimate representation of the struggle of Black Power because they provided leadership to the movement and had the capacity to build Black Power around the notion of territoriality and self-protection (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 66). Unlike other movements, their solution of armed self-defense resonated with the people and spread. In challenging the state’s exclusive right to the use of armed force, they were also challenging the power structures within the community “they were able to forcibly assert their political agenda through their armed confrontations with the state” (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 391). In other words, they used the weapons of oppression to elevate themselves and negotiate with the police, and by extension the state, on equal standing.

This assertion of power against the oppressive regime did not come without backlash. The “police see themselves as defending the interests of white people against a tide of Black insurgence”, which demonstrate who the police, as an extension of the state, intend to protect and who they consider to be a threat (Blauner, 1969, 405). As the Black Panthers gathered followers and influence, police more closely and frequently surveilled their leaders and members in an attempt to find anything illegal they were doing so they could arrest them and once more assert their dominance. The state and federal governments actively created policies to mitigate the actions of black activist groups. In response to the spread of Black Panther’s ideas of self-defence, the California legislature proposed and passed the Mulford Act (or “the Panther Bill”) that would outlaw carrying a loaded firearm in public (Bloom, Martin, 2013). Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) run by the FBI specifically had a section targeting what it considered Black Extremist Groups, such as the Nation of Islam, in response to the rise in Black Nationalist groups at the time (Bloom, Martin, 2013; Moore, 1981). Its stated goal was to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of Black Nationalist, hate-type groups” (FBI, 2, 1967).

The government’s actions demonstrate the federal consolidation of power that Marx discusses: the federal government was able to act in a unilateral way. It directed police actions and manipulated the media in order to justify police attacks and isolate the Black Panthers from both moderate racial uplift groups and society at large, portraying them as violent and white-hating (Moore, 1981, 12). State backlash demonstrates the processes by which elites maintain their power. Portraying the Panthers as a hate group, discrediting their platform and leaders, and criminalizing their activities aimed to further marginalize their voices create a white unity against the portrayed threat, and fracture ‘extremist’ black nationalists from more ‘moderate’ groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (Moore, 1981, 11). By doing so, they create a more stable nation-state, where existing power structures are not constantly challenged and disrupted, and groups doing so are seen as fringe or extremist and are thus viewed as illegitimate. While it is a more aggressive approach to consolidating a nation-state than post-Civil War reconstruction, it was, nonetheless, an attempt to create stability and order within the United States and reproduce the exclusion of African-Americans from political power.

A comparison with the earlier radical movement Garveyism

In Black Against Empire, Bloom and Martin argue that “widespread mobilization along revolutionary black nationalist lines was unique to the late 1960s” (2013, 391). They argue it neither happened before nor has it happened again. However, Black nationalism and Black consciousness were not unique to this particular era. Earlier in the century, W.E.B. Du Bois was a staunch advocate for Pan-Africanism and Black nationalism and pride (Marx, 1998, 220). However, much like the Civil Rights Movement and RAM, racial improvement groups such as Du Bois and his NAACP “remained relatively focused on the small black middle class” (Marx, 1998, 221) and “depended upon the upper classes, both white and Negro, for intellectual and financial support” (Cronon, 1955, 37). Marcus Garvey’s movement, like the Black Panther Party, appealed to the poor, urban Black communities of the north. In both cases, the feeling of otherness in terms of race and power, born out of the urban ghettos of the 1920s and 1960s, respectively, shaped their particular platforms of Black identity. Their own brands of the ‘New Negro’ movement and Black Power developed because there was no recourse for the violence they faced (Ewing, 2014, 51). Because they were Black and poor, people within these communities did not have access to channels of justice. Their success in addressing problems that urban black communities faced, in a language they could understand, led to their mass following. Building tensions within post-World War America and a growing sense of Black Nationalism created the perfect conditions for the radical, self-help movements of Garvey and the Black Panthers to emerge as a mobilizing power for mass politics. The understanding of a Black identity as a counterweight to white imperial power makes the Africanism nationalism of Garveyism and the Black Power espoused by the Black Panthers a particularly interesting comparison.

A similar wartime migration occurred in the First World War as in the second. This migration transformed “small pockets of black settlement in the urban north into dynamic, volatile ghettoes”, fraught with unemployment, low wage workers, disenfranchisement and rising food prices (Ewing, 2014, 68). This Great Migration to northern and western cities was a catalyst for white backlash. Angered by increased competition for jobs and fuelled by prejudice, racially motivated violence broke out. In 1917, there were riots in East St. Louis due to the “employment of Negroes in a factory holding government war contracts” and the Red Summer of 1919 saw race riots in 26 American cities (Cronon, 1955, 31).

For the Black Panthers, their version of Black Power developed out of the local circumstances of a postwar urban redevelopment and ineffectual racial equality groups like RAM. Born in the postwar ghettos of Harlem, Garveyism developed from an initial movement led by Hubert Henry Harrison starting in 1917 (Ewing, 2014, 69). Called the “New Negro” movement under Harrison’s Liberty League, they sought “to celebrate militant and respectable black masculinity, and to replace an old cadre of elitist and ineffective black leadership with a new brand of uncompromising mass politics” (Ewing, 2014, 51). In a postwar period of global reconstruction, they thought that Du Bois’s demands of recognition of African-Americans and colonial grievances were not pushing hard enough (Ewing, 2014, 59). Like the Black Panthers, their message was that the period of compromise was over, and across Harlem, people agreed that self-defense had legitimate value and valor (Ewing, 2014, 80). In the face of increasing frustration and unemployment, Black groups “met white violence with coordinated and often cathartic acts of self-defence” (Ewing, 2014, 78-9). Garvey adopted these sentiments and was able to translate it into a language that had mass appeal, sending it beyond the borders of Harlem’s ghettos. Garvey launched his platform in the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA) at the end of World War I in much the same way Seale and Newton instituted their platform of self-defense in the Black Panther Party.

In this period, the distribution of resources was also far from equal. Like the postwar world that the Panthers emerged in, local political, economic and social positions of power were largely out of the hands of Black communities. Garvey argued “the black man was a consumer and not an independent producer” (Martin, 1976, 33). His solution was to put Black people in control of their own economies, “[d]rawn from Booker T. Washington’s philosophy that Negroes must become independent of white capital and operate their own business activities” (Cronon, 1955, 51). Garvey pioneered the Black Star Line in 1919, a shipping company that would be completely independent of white capital, employing Black workers and being owned only by Black shareholders. While the Black Panthers used guns and police patrol to exercise self-protection, Garvey’s vision manifested itself in economic uplift and ownership of the means of production. These platforms developed from feelings of urban exclusion from positions of power within the oppressive political, economic, and police institutions, and race-making and mobilization from below occurred in the response to such exclusion.

Garvey faced the same scrutiny and surveillance from the American government that Black Panther leaders would experience nearly four and half decades later. He was constantly watched by authorities. When they could not find anything wrong or illegal in Garvey’s actions, they switched tactics and tried to establish him as an “‘undesirable alien’ and to effect his deportation” (Ewing, 2014, 114) in an attempt to discredit his character and ideas and prevent his rise as a Black resistance leader. Like COINTELPRO, this heavy surveillance suggested how threatening the American state found grassroots Black mobilization to the status quo distribution of power.

Internationally, in response to Garveyism and other pan-Africanist philosophies, right-wing politics increased in Europe, whose leaders fought to re-establish strong colonial control in Africa (Ewing, 2014). White elites had a vested interest in maintaining the political and economic order of the exploitation of Black people in African nations and in the diaspora. In line with Tilly’s framework, to maintain these categorical racial boundaries would allow the continuation of returns from the extraction of labour from subordinate groups, in this case from Black labour, without fully sharing those returns. Rather, the distribution of solidarity-generating benefits remained among themselves (Tilly, 1998, 89). Like when the Panthers fought domestic imperialism, the backlash to anti-colonial assertion was to more strongly re-assert the existing international imperial order in an attempt to deter the threat of self-determination (Ewing, 2014, 110). For white elites in both post-war eras, racial uplift threatened their monopoly on power, resources and capital.

What both the Black Panthers and UNIA were able to provide was a legitimate political entity capable of enacting change, located in a particular time and space. It was not simply mass mobilization, but rather a specifically anti-status-quo political counterweight, challenging the local institutions themselves. For the Black Panthers, the deaths at the hands of the police was an urgent call to action that institutions of power needed to be under the control of the people whom they claimed to be protecting. Seale and Newton began their mission of asserting power over the police. Newton (1973) recalls, “[b]y standing up to the police as equals, even holding them off, and yet remaining within the law, we had demonstrated Black pride to the community in a concrete way” (145). Furthermore, they were able to utilize their own Survival Programs to give tangible services to the community while also pointing to the failed governmental programs meant to revitalize the city and ameliorate poverty. Their Ten Point Platform laid out the specific aims of the party in simple terms that people could understand and support.

Similarly, “radical Garveyism urgently articulated a moment in which the outlines of the postwar world were uncertain, and in which peoples of African descent sensed an opportunity to redraw them” (Ewing, 2014, 77). While the UNIA had a more international goal, it linked local conditions to a broader international pan-African network of cooperation by allowing local UNIA branches to implement their own business enterprises (Martin, 1976, 35). Furthermore, it engaged in political negotiations, with Professor Jean Joseph Adam as its ambassador to the League of Nations (Martin, 1976, 45). In both cases, changes in oppressive race-making from above presented an urgent need to mobilize to action.

Key to both revolutionary movements was the use of newpapers to desseminate their political platforms and relevant current affairs; for the Black Panther Party, the Black Panther, and for UNIA, Negro World. Both a propaganda tool and counterweight to white-controlled media, these newspapers provided invaluable information to a wide audience, providing a way to mobilize, inform and connect a larger audience. This was particularly important because the white media had a vested interest in discrediting these movements. The Black Panther and Negro World were a way to establish Black controlled and distributed media, and a direct challenge to one aspect of external, white power.

Garveyism differed from the Panther platform largely due to the time in which they developed. During the post-World War I era, the colonial power remained in Europe, with occupation still occurring on the African and Asian continents. Yet, similar to a post-Civil War America, World War I showed a fracture in white power: “‘the veneer of European invincibility had been torn away, that the moral authority and leadership of Western civilization had been undermined”’ (Ewing, 2014, 51). Race-making from above was based on the reconciliation and stability of the white, imperial world. While America still played a role, particularly in the oppression and violence against African-Americans, the context of a war of European powers necessitated a more global understanding of Black Nationalism, with an emphasis on the return to Africa. For Garvey, “[t]he only answer to white power in America was black power in Africa” (Ewing, 2014, 118). In the era of the Black Panther Party, the rise of a bipolar world in which America was one of the two global superpowers changed the balance of power away from European colonialism to that of American imperialism, displayed through the wars in Korea and Vietnam. Two major fundamental differences result from these contextual differences.

First, Garvey and the UNIA refused to build coalitions with white groups; there was an “exclusion of white people from membership in the UNIA and affiliated organizations” and they also rejected white philanthropy (Martin, 1976, 30). Because of the local conditions of segregation and the global conditions of hierarchical categorical exclusion, Garvey saw this as a necessary way to “ensure self-reliance and equality for the downtrodden African race” (Martin, 1976, 32). The Black Panther Party, on the other hand, was “strongly committed to interracial coalitions,” including, for example, with the anti-imperial white left (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 7, 104). Because the basis of their platform focused on American imperialism (which is more specific than white imperialism), any groups with similar grievances were seen as allies.

Secondly, the Black Panthers rejected pan-Africanism because they felt no real claim to Africa, rather that “African-Americans occupied a limited geographical space” (Tyner, 2006, 114). The development of their policy was more specific to the local conditions and knowledge that leaders like Seale, Newton and Eldridge Cleaver saw as problematic in their community. When connecting to other movements internationally, the Black Panthers’ alliances with Cuba, North Korea, and North Vietnam signify they were all fighting the same enemy: America’s oppressive imperial power (Bloom, 2013, 269-302).

Part of Garvey’s strong belief in an African nation is a result of the fact that Garvey himself was not American, but Jamaican and started UNIA in Kingston (Ewing, 2014, 71). Garveyism spread because of the similarities between Harlem and Kingston. Like the Panthers’ international coalitions sought to resist American imperialism, Garveyites around the world were united against European colonialism because these were the colonial conditions of their respective eras. The reasons for their differences reinforce my argument that it is local geopolitical knowledge, situated in a particular time and place, of particular inequalities in power, resources, and legitimate force that shape the development of a revolutionary movement premised on Black identity with goals of self-determination.

Conclusions and legacies of the Black Panther Party

When Seale and Newton formed the Black Panther Party in 1966, they sought to challenge and dismantle the colonial American state, and take control of the institutions within their community. Their expression of Black Power and platform of reclaiming and protecting racialized space, reflected and responded to the local geopolitical context. While the structural conditions the Panther’s targeted were more diffuse than the narrower legal goals of the Civil Rights Movement, contrary to Marx’s framework, such Black mobilization in the North had both specific targets and made concrete gains. Riots were not simply just “an assertion of black identity and anger” (Marx, 1998, 239), but were also in direct response to police brutality and lack of political power to determine the outcomes and justice within one’s own community, reflecting “the colonized status of Afro-America” (Blauner, 1969, 398). The assertion of Black identity was to reclaim spaces as their own, underpinned by an understanding that “social problems of the Black community will ultimately be solved only by people and organizations from that community” (Blauner, 1969, 407). The Black Panther Party understood the grievances of the community and were able to create a platform that spoke to the local problems of the black community of Oakland.

One of the concrete gains of the movement was a greater awareness of police brutality and abuses. Even if the Panthers did not manage to completely eradicate it, even in 1973, Newton notes “it is the rare police commissioner who has not tried to establish some form of public relations between police and Blacks” (Newton, 1973, 330). Furthermore, the trial of Newton, and the subsequent ‘Free Huey’ campaign, raised awareness of how the American justice system inherently worked against Black defendants. His case, for example, brought to national attention the unfairness of a majority white, middle-class jury for a poor, Black defendant, and resulted in “courts all over the country have become aware of a defendant’s right to be tried by a jury of his peers”, by people who understand the circumstances that brought them before the court in the first place (Newton, 1973, 197). Newton’s trial compounded with the controversial assassination of Fred Hampton to demonstrate how far the state was willing to go to suppress collective Black identity. The two exposed to both Black and white citizens the systematic way that the police and justice system targeted and unfairly tried young Black men. In response to public outcry, the government and the police were forced to change their tactics to be (or at least appear to be) less overtly discriminatory.

Beyond the justice system, the Panthers were able to build political networks as they rose to dominance on the West Coast. In 1972, Seale ran for Oakland mayor and Elaine Brown for city council. Even though neither of them won, they made it to the end of the race, demonstrating African-Americans could credibly run for office. They paved the way for later politicians and political initiatives. Furthermore, being seen as a legitimate organization that represented the interests of the people, they registered many Black voters and got the Black community out to vote. A significant way to leverage political power en masse, this had real political impacts. For example, the Panther’s grassroots support of Lionel Wilson’s campaign was essential for his election as Oakland’s first African-American mayor (Self, 2003, 785).

This question of why Oakland specifically is more difficult to address because urban situations across America mirrored Oakland in many ways. For example, the 1967 summer riots in Newark and Detroit were indicative of the same symptoms on the other side of America; residential segregation along racial lines, inequality of resource and power distribution, and an oppressive, racist police force that had violently controlled the community (Bloom, Martin, 2013, 83). Perhaps it is because Oakland was a ‘pioneering participant’ of the War on Poverty (Self, 2000, 764) and “a poster child for federal antipoverty and employment programs in the mid-1960s” (Self, 2000, 773) that failures of these programs to address structural issues underpinning poverty and unemployment were so salient. The contrast between the massive boom in the neighbouring Port and the unfulfilled promise of eradicating poverty may have exponentially magnified feelings of injustice that did not happen in other cities. As a result, police brutality within the community felt like a bigger blow, as it only added insult to injury, hurting a community that was still suffering disappointment from a different arm of the state.

The people needed recourse. Newton recognized “the rising consciousness of Black people was almost at the point of explosion” (Newton, 1773, 110); these were the perfect conditions for mobilization. As members of the community who had experienced all this, Newton and Seale rose above the rest because they were willing to take a stand that both directly challenged oppression and put power, philosophically through Black Power and physically through guns, into the hands of the people in a way that other groups at the time were unwilling to take. Voicing the opinions of poor urban Black people and fighting for the causes that affected them everyday, these two leaders were able to mobilize the people because they understood and related to them in a way the colonial state and other more moderate or middle-class racial uplift groups could not.

It was an intersection of conditions that led to anger and feelings of injustice with Newton and Seale, two leaders who knew how to respond in a way the people could connect with. While the seeds to mobilization were there in the form of ideas and platforms, it took the right people to connect with the people the movement represented. Similarly, in Harlem, Harrison’s Liberty League developed race-first politics encompassing the militant sentiment of the time (Ewing, 2014, 69), but he was unable to take off nationally. It took Garvey’s vision of Black Nationalism and adoption to Harrison’s principles of “radical, mass-based alternative to the NAACP” (Ewing, 2014, 72) to build a successful national movement. Perhaps this difficulty in answering the questions of “why Oakland or Harlem specifically?” reflects the reason these two movements had such mass appeal: their platforms addressed local conditions but these conditions were shared by poor urban African-Americans across the country. Without the common grievances between cities, the movements could not have successfully mobilized the masses in a way that transformed racial consciousness and connected people to the cause.

Race-making from below mobilized around systematic problems faced by poor urban African-Americans. It was clear previous strategies were ineffectual at addressing these particular problems. Members of the community they claimed to represent, with their local geopolitical knowledge of the conditions of Oakland in the late 1960s, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton’s revolutionary vision provided solutions to salient problems that movements before had not and gave the people a way to take control of and defend their own physical spaces. It was the conditions created by race-making from above by both the state and economic institutions out of which the Party was born.

The specific geopolitical context that gave rise to the Black Panther Party is important because similar inequalities and patterns of police brutality still exist today. While the Panthers were able to build a Black political consciousness and enact important political and police engagement, the recent prolific murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police demonstrate that many structural problems remain rife. Nearly a century after Garvey started UNIA, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, similar to the Panthers in its militancy (Clayton 2018) and vitriolic conservative backlash, was galvanized by the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 (Ray, et al. 2017), like Denzil Dowell’s death in 1967. While the movement is still relatively young, the use of social media to spur collective action and record and share instances of police brutality (Ray, et al. 2017) has created a faster, more visceral alternative to the Panthers’ and UNIA’s use of newspapers to increase political visibility and foster solidarity. However, the diffuse power structure of BLM and broad concern with excessive policing, police brutality and legal reform across America (Clayton 2018) may hinder its ability to speak directly to people the way Newton and Seale did and provide direct solutions to locally specific problems, like Survival Programmes and armed self-defense. The tactics and focus of the Panthers may thus still be relevant in tackling systemic racism today.

By 1966, anger was brewing in Black communities about the urban injustices that had been committed against them. As the built environment began to crumble in the fallout of white flight to suburbs and disinvestment of inner cities, and communities lived in fear of unfettered police violence, the urgency to act was reaching an all-time high. The Black Panther Party was willing to harness these attitudes in a coherent plan of self-defence and lead the colonized urban ghetto to liberation: “The time had come for action” (Newton, 1973, 110)!

Bibliography

Blauner, Robert. 1969. "Internal Colonialism and Ghetto Revolt." Social Problems 393–408.

Bloom, Joshua, and Waldo E. Jr Martin. 2013. Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkley: University of California Press.

Cronon, Edmund David. 1955. Black Moses. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Ewing, Adam. 2014. The Age of Garvey. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fanon, Franz. 2004. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

Gilpin, Robert. 1981. War and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hudson, Michael C. 1988. "The Problem of Authoritative Power in Lebanese Politics: Why Consociationalissm Failed." In Sustainable peace: Pwer and Democracy after Civil Wars , by Nadim Shehadi and Dana Haffar Mills, 224-239. London: I.B. Tauris.

Martin, Tony. 1976. Race First. Westport and London: Greenwood Press.

Marx, Anthony W. 1988. Making Race and Nation: A Comparison of South Africa, the United States, and Brazil. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, Dhoruba. 1981. "Strategies of Repression Against the Black Movement." The Black Scholar 12 (3): 10–16.

Newton, Huey. 1973. Revolutionary Suicide. New York: Stronghold Consolidated Productions Inc.

Rice, Eugene, and Anthony Grafton. 1994. The Foundations of the Early MOdern Europe, 1460-1559. New York: Norton.

Self, Robert O. 2000. ""To Plan Our Liberation": Black Power and the Politics of Place in Oakland, California, 1965-1977." Journal of Urban History 26 (6): 759–792.

—. 2003. American Babylon: race and the struggle for postwar Oakland. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Somers, Margaret R. 2008. Genealogies of Citizenship: Markets, Statelessness, and the Right to have Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation. 1967. "Freedom of Information and Privacy Act, Subject: COINTELPRO Black Extremists." The Federal Bureau of Investigation . 08 25. Accessed 2021. https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists/cointelpro-black-extremists-part-01-of/view.

Tilly, Charles. 2002. Durable Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tyner, James A. 2006. "Defend the Ghetto: Space and the Urban Politics of the Black Panther Party." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96 (1): 105–118.

Weber, Max. 2013. "Politics as Vocation." In From Max Weber : Essays in Sociology, by Max Weber, H.H. Gerth, C. Wright Mills and Bryan S. Turner. London, New York: Routlege.