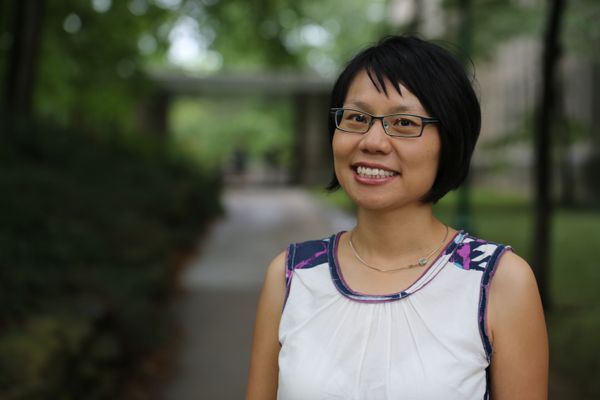

In August 2020, Jisoo Choi sat down with Camille Delaney-Mcneil, Director of Programs with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra OrchKids.

Jisoo Choi: Could you briefly describe what OrchKids does with respect to its programs and the impact it seeks to have?

Camille Delaney-McNeil: OrchKids, in short, is a “music for social change” program. It was inspired by the El Sistema movement from Venezuela, which was led by Dr. Jose Abreu and quickly spread internationally. The whole concept is that the intervention of music early on in life can change the trajectory and course of young people’s lives and the opportunities they are afforded. OrchKids very much embodies the spirit of that concept: community reflecting our community as accurately as we possibly can—being responsive to our community—but more specifically creating avenues, networks, connections, and conduits for our youth in Baltimore City to make strides in the world to change anything they want to change about their world and have a path forward.

We’ve already seen the effects of that. Our program is twelve years old, and we have a young lady who’s been in our program for all twelve years. She comes back as a volunteer. And although COVID-19 interrupted the brilliancy of this year, this was her first year of college. She’s a first-generation college student, and she is attending on a full scholarship for all four years because of her instrument. She’s not even doing a music performance degree; she’s doing music business and some other things. That just goes to show that her world has expanded so much more because she now has that opportunity. And she’s the trailblazer in her family to do something like that. So that’s a big deal. And that’s what we want to foster with OrchKids.

The other important thing is that we are actively engaged in supporting change in our community outside of the arts and music program. Obviously, there’s lots to do within music education itself, so that’s a whole other conversation. But the social ills, the lack of access that we have in our city—particularly for our youth—even around things like transportation and technology access, are things that have come up during this time as well. We’re asking, “How do we as a program make systemic changes? What can we offer or who can we put our students and families in contact with? How can we provide a wraparound arm of support for them to tell us what direction they need to go?” So it’s also very important to understand that we cannot come in as a program and direct our community and say, “this is what you have to do.” That would be irresponsible, but a lot of programs unfortunately do that. So it’s extremely important that the staff and leaders of the program are from the community, work with the community, and are a part of the community. And that’s why we hire parents from our program to be team members. We have a full-time team member right now who is a parent of three kids in our program, one of which was the young lady who was the first-generation college student we spoke of. So we make sure that we’re involving the community. We fill our positions and have thought partnerships with parents all the way through our school partners and principals just to be as reflective and authentic as possible.

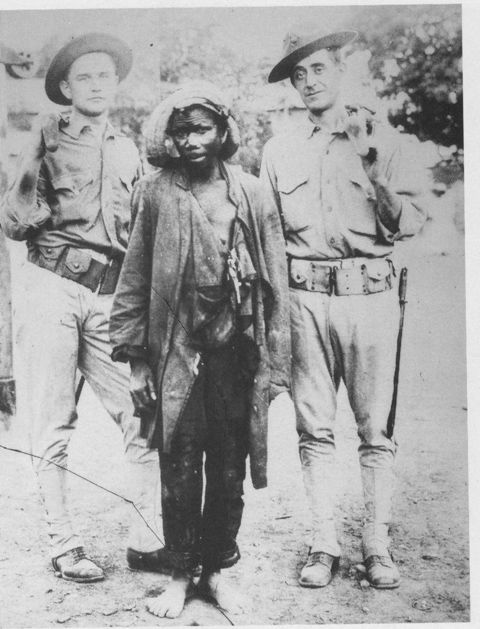

JC: That’s awesome. It’s especially encouraging to hear that OrchKids works with people who are consciously involved in and from the Baltimore City community, because many social change programs seem to have a detachment—a white savior attitude—toward the people they serve. It’s really lovely to see that everybody at OrchKids is intertwined with the Baltimore City experience. Could you explain a little more about what is especially special about adapting the El Sistema initiative for Baltimore City, in its structure, programs, or otherwise?

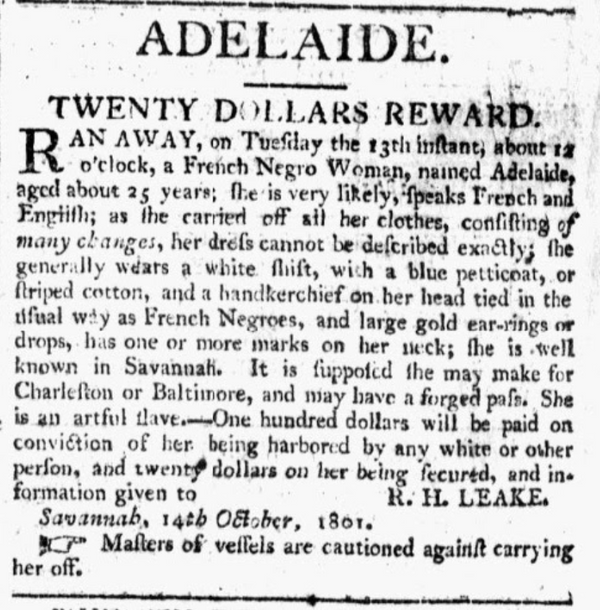

CD: On a structural level, having ensembles and mixed-level instruction, cultivating peer mentorship bonds, and involving the whole family in the community are core principles that I take away from Sistema that are a very vibrant part of what we’re trying to do at OrchKids. The critical differences lie in how we design our program to match what is relevant to Baltimore. What I’ve found when program team leaders or music directors come from some of these Sistema-based countries in Latin America and in various other places, they have a very pronounced mindset as to the vigor and excitement about Western classical music that tends to be adopted as the be-all and end-all. That’s something we do very differently in Baltimore. We heavily emphasize student creation—student voice and composition—so that the sounds are from Baltimore. The interactions and feelings the students are experiencing are very different from what a young person might be experiencing in Venezuela. There’s really no correlation in Venezuela to the long history of systemic racism against Black Americans in this country. So we have some differences in what matters are important to us and what types of music we hold or revere. I don’t know that you might go to other programs in other countries where non-classical genres are revered with the same amount of appreciation as classical genres. That’s very different.

The other thing is that as the U.S. is one of the wealthier countries on this planet, our students aren’t necessarily deprived of certain things like [having a personal] cell phone. That’s not to say that it’s not the case for some of our students, which is a very present reality, but that might be very different in a country like Venezuela. So the experience of being able to just show up with your instrument and play may not carry the same amount of value to a Baltimore student as to a Venezuelan student. So we tailor it to ask, “How can you express yourself using this instrument, to say what you want to say and make the change you want to see in your community?” Those are some of the very basic differences [between El Sistema and OrchKids].

Also in how we structure, in some other internationally based programs, there is a gradient mix of older students who are really proficient on their instrument mixed into a class with a very beginner student, like a student who is seventeen in a class with a student who is nine years old. That’s something we’ve found to be not as effective here in Baltimore. We tend to lose students when they feel that they don’t have a separate, more specific thing to be a part of. So within our program we have age-appropriate structures. But we also enforce heavily the idea of mentorship and the idea of giving back something that was instilled in you by building someone else up while you are being built up.

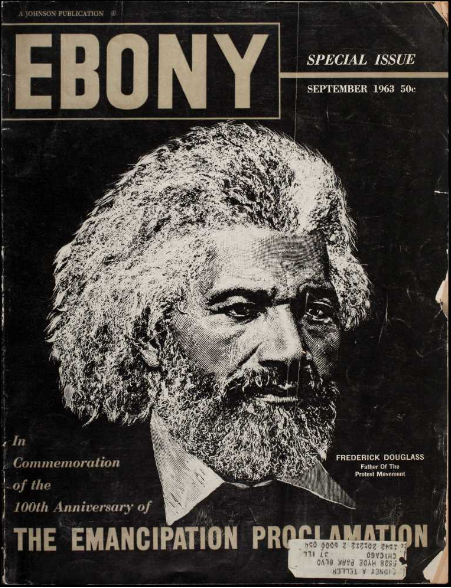

JC: You’ve mentioned that not only in Baltimore but all across America and Europe, there’s this sense that the Western canon of classical music is the be-all and end-all. I find that to be true to my experience and the environment in which I learned classical music. And in light of the current political climate there have been a lot of Black musicians and other musicians of color speaking out through social media against racism and anti-Blackness in particular in classical music. How do you think OrchKids and the music for social change initiative reckons with those stories of racism and this entrenched white supremacy in the artistic environment?

CD: It’s a constant battle. It’s a constant self-reflection, because no one is on some perfect scale of “wokeness.” People need to check themselves and their individual biases every day. All of us hold biases. It’s not just one group of people that hold it; we all hold this implicit bias. We have to find out where those areas are and we have to make those constant adjustments. One of the goals of OrchKids is to grapple with that and to really ask that question in what we do and what we’re practicing, the repertoire we’re choosing and the instruments that we’re teaching on.

Are we upholding certain structures in place that we don’t really intend to? That’s an internal question we’ve come to, and there have been ways that we’ve addressed that in terms of some of the things that we offer. Again, I’m talking about the genres and the repertoire that we choose to teach our students. We teach them everything. I’m a conservatory-trained musician myself, and grew up in classical music. I was trained to be a Western white classical musician. We have this misconception that if you master this particular canonical set of music, then you become an elevated musician. My perspective that I’ve grown into is that if I can only do that, and can’t play by ear or play in different genres or adapt my style with facility, then how am I the superior musician to someone who can do all those things, who can play classical white music and also do everything else brilliantly? That, to me, is a more well-balanced, well-trained musician. So we need to redefine what we revere, ultimately. We question what we define as excellence when we train our students, because if excellence only lives in being able to play a Mozart concerto really well with the cadenza and all the ornaments, that’s not enough.

We also make sure that our students are at the forefront of our decision-making. And all of our team members are so committed to that, and we fill the program with people who are mission-driven and who understand the work that they’re doing. All of us have these great and unique relationships with our students, where they feel comfortable to text us and ask us about things unrelated to the program. We can help them with academic or other things, and that’s the kind of rapport we’ve built. And in those side conversations, they’ll give us feedback on OrchKids, about what they didn’t like or thought was inefficient. And then we make design changes based on that. We put together student focus groups quite regularly. And the whole vision is that we all are replaced on day by the students who grew up in this program because they are the experts, not us. They grew up in it. They are products of it. So we are facilitating pathways of making sure that students can be teachers in our program. We already have two to three students who have graduated and have started to teach in our program. When that is a priority, you’re going to actively combat that destructive narrative that racism and biases are presenting themselves in our art form.

In our program, we are doing that work constantly, in our training and professional development for our team. There are certain required readings that we have to do, which include a history of racism and segregation in Baltimore City. So we have an expectation of what’s required of people when they show up to the classroom and of what they’re feeding into our kids. And then we responsibly reflect the feedback our students are giving. That to me is exactly the work you’re talking about.

JC: It’s really wonderful to hear about the cyclical pattern of students returning and teaching, because that shows the true impact they received and how much they loved this program. I have some personal experience, however limited, with OrchKids; I was a summer volunteer in 2017. I remember there were other volunteers who had been students in the program, as well as volunteers from different counties and different schools. I’m from Howard County and as close as it is to Baltimore City, it’s a very different environment. It’s one of the wealthiest counties in the country, and people like me who went to school in Howard County but were volunteering at OrchKids come from a very elevated place of privilege. And as non-full-time staff members, we didn’t get as much time to do such training or readings on racism in Baltimore and classical music. Because empathy without firsthand experience can only go so far, what do you wish volunteers like me knew more about going in?

CD: This isn’t one individual’s fault, but the fault of an entire educational system. I think students at the top educational levels are just not taught a complete history. Even taking Baltimore City out of the equation, your upbringing and schooling in this country is incomplete. Incomplete in terms of historical knowledge and accuracy, interns of the aggressive rallying around racism that has built this country up and that permeates and influences everything that happens here. So yes, progress is made, but the reason we keep repeating certain things in our history is because we’re not taught it fully. So I can’t even blame people for not showing up knowing things already. One has to be a self-driven discoverer interested in challenging what is presented to them. I would say to anyone who is coming to volunteer with such an organization, ask yourself why you’re doing this and what you hope will be a result of your presence there. Because if it’s to write a line in a résumé or to eventually get a recommendation, that’s not the point. That’s the first thing. The second thing is to do your research. I wish people would just do a basic amount of research and come with some questions, because we do have a mission. We do have a purpose. So when one volunteers, I want them to come in knowing why they’re there and ready to help support that action, however menial the task. It may be to create a flyer, but you know that that flyer is going to be helpful for families to communicate, because not everybody has access to consistent Internet and email so this is the only way to get accurate information. So that’s going to be the best darn flyer you put together. You need that kind of intentionality. We’re trying to build a bigger culture around being intentional and focused with everything we do. That’s even hard to do in everyday life, trying to be super intentional with every personal task. But at least when I show up for work and when I show up to volunteer, I am intentional about what I’m doing there. I’m not pitying, “oh, these poor kids need me,” or “these kids are so poor,” and so on. I ask the question, why does this program exist? Why is there even a need for this program? When you start asking critical questions like that, you really start to understand that this is so much deeper than a music lesson. A whole program literally had to be created because students of color were not getting good access to arts education that folks in Montgomery and Howard County get. It’s just a part of your everyday routine; it’s on your schedule to have some sort of arts program participation and it is not cut from your budget. Then you understand, okay, there’s inequality and lack of access here. Well, why is it only lack of access in these areas? Oh, they’re predominantly communities of color. So that, I hope, would be the intention of the volunteers.

JC: Thank you for that. Now to zoom out from Baltimore to the American cultural sphere at large—in the past month we’ve seen any number of orchestras, theaters, museums, and the like post statements against racism and police brutality on their websites and social media pages. I was wondering, what are the responsibilities of cultural organizations, now, beyond those words and in concrete actions? And how is that heightened for OrchKids as a program whose students are mostly people of color?

CD: One thing I will say is that we will never politicize or weaponize our students for an agenda.

We're trying to create change. Of course we’re behind anti-racism and of course we’re about building Black and Brown voices up. That’s literally the heart and soul of our program.

The institution that oversees OrchKids [the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO)] is a predominantly white institution. But what people don’t often realize about OrchKids is that though we are affiliated with the BSO, we have a separate operating budget and our own designated leadership and fundraising, which allows for a certain level of autonomy in our approach and in how we govern ourselves. The BSO has put out a statement, and various other orchestras across the country have done so as well, addressing some of those very revealing needs. Most of the people of color in the organization are from the OrchKids team, unfortunately. We [at OrchKids] are 50:50, if not 51:49, on our person of color to white ratio.

As for the role of arts and cultural institutions, I think they have often been leaders in making change. I think about people like Marian Anderson and various other artists who used their art form to cause systemic change to occur. People rally around the arts and around music, and artists help change the tide, too. Music and art and these enjoyable experiences bring people together. So I think it is on institutions—arts institutions in particular—to lead the charge and demonstrate how change can occur within a huge entity: what that looks like for hiring practices, for setting budget decisions, for getting community involvement. I think it’s the responsibility of arts organizations, whether they recognize it or not, to set the tone for what change can be.

JC: To continue that discussion, what kinds of discussions have been ongoing among the teachers and staff of OrchKids and also the BSO to further that change and to make the most of this movement?

CD: I am proud to say that our organization—including the parent organization, the BSO—is working very actively on a plan and has a working group together to push forward matters of EDI [equity, diversity, and inclusion] work. Also, right now, we’re strategizing on figuring out a way to hold ourselves accountable on all levels. That is work that’s now being adopted by the board, team members, staff, and musicians. I won’t say that this is the first time by any stretch of the imagination, but it feels like a very palpable time where all levels of our organization are kind of on the same page and also very open to how we’re held accountable for that. So I will say, I’m happy that as a global organization we are moving in that direction and that there is leadership responsive to the tough questions and to making sure that this is not yet another “let’s show face for a couple of weeks and then it’s back to business as usual” situation.